Knowledge Systems and Local Practice in Rural Thailand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lao in Sydney

Sydney Journal 2(2) June 2010 ISSN 1835-0151 http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/ojs/index.php/sydney_journal/index The Lao in Sydney Ashley Carruthers Phouvanh Meuansanith The Lao community of Sydney is small and close-knit, and concentrated in the outer southwest of the city. Lao refugees started to come to Australia following the takeover by the communist Pathet Lao in 1975, an event that caused some 10 per cent of the population to flee the country. The majority of the refugees fled across the Mekong River into Thailand, where they suffered difficult conditions in refugee camps, sometimes for years, before being resettled in Australia. Lao Australians have managed to rebuild a strong sense of community in western Sydney, and have succeeded in establishing two major Theravada Buddhist temples that are foci of community life. Lao settlement in south-western Sydney There are some 5,551 people of Lao ancestry resident in Sydney according to the 2006 census, just over half of the Lao in Australia (10,769 by the 2006 census). The largest community is in the Fairfield local government area (1,984), followed by Liverpool (1,486) and Campbelltown (1,053). Like the Vietnamese, Lao refugees were initially settled in migrant hostels in the Fairfield area, and many stayed and bought houses in this part of Sydney. Fairfield and its surrounding suburbs offered affordable housing and proximity to western Sydney's manufacturing sector, where many Lao arrivals found their first jobs and worked until retirement. Cabramatta and Fairfield also offer Lao people resources such as Lao grocery stores and restaurants, and the temple in Edensor Park is nearby. -

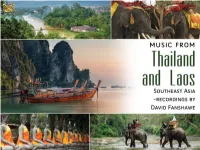

2588Booklet.Pdf

ENGLISH P. 2 DEUTSCH S. 8 MUSIC FROM THAILAND AND LAOS SOUTHEAST ASIA – RECORDINGS BY DAVID FANSHAWE DAVID FANSHAWE David Fanshawe was a composer, ethnic sound recordist, guest speaker, photographer, TV personality, and a Churchill Fellow. He was born in 1942 in Devon, England and was educated at St. George’s Choir School and Stowe, after which he joined a documentary film company. In 1965 he won a Foundation Scholarship to the Royal College of Music in London. His ambition to record indigenous folk music began in the Middle East in 1966, and was intensified on subsequent journeys through North and East Africa (1969 – 75) resulting in his unique and highly original blend of Music and Travel. His work has been the subject of BBC TV documentaries including: African Sanctus, Arabian Fantasy, Musical Mariner (National Geographic) and Tropical Beat. Compositions include his acclaimed choral work African Sanctus; also Dona nobis pacem – A Hymn for World Peace, Sea Images, Dover Castle, The Awakening, Serenata, Fanfare to Planet Earth / Millennium March. He has also scored many film and TV productions including Rank’s Tarka the Otter, BBC’s When the Boat Comes In and ITV’s Flambards. Since 1978, his ten years of research in the Pacific have resulted in a monumental archive, documenting the music and oral traditions of Polynesia, Micronesia and Melanesia. David has three children, Alexander and Rebecca with his first wife Judith; and Rachel with his second wife Jane. David was awarded an Honorary Degree of Doctor of Music from the University of the West of England (UWE) in 2009. -

Development of Lifestyle Following Occupational Success As a Mor Lam Artist

Asian Culture and History; Vol. 7, No. 1; 2015 ISSN 1916-9655 E-ISSN 1916-9663 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Development of Lifestyle Following Occupational Success as a Mor Lam Artist Supap Tinnarat1, Sitthisak Champadaeng1 & Urarom Chantamala1 1 The Faculty of Cultural Science, Mahasarakham University, Khamriang Sub-District, Kantarawichai District, Maha Sarakham Province, Thailand Correspondence: Supap Tinnarat, The Faculty of Cultural Science, Mahasarakham University, Khamriang Sub-District, Kantarawichai District, Maha Sarakham Province 44150, Thailand. E-mail: [email protected] Received: July 9, 2013 Accepted: July 15, 2014 Online Published: September 22, 2014 doi:10.5539/ach.v7n1p91 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ach.v7n1p91 Abstract Mor Lam is a folk performing art that originates from traditions in the locality and customs of religion. There are some current problems with Mor Lam, especially in the face of globalization. Mor Lam suffers as traditional beliefs and values decrease. Society is rapidly changing and the role of the mass media has increased. Newer media provide knowledge and entertainment in ways that make it impossible for Mor Lam to compete. This research used a cultural qualitative research method and had three main aims: to study the history of Mor Lam artists, to study the present conditions and lifestyle of successful Mor Lam performers and to develop the lifestyle of successful Mor Lam performers. The research was carried out from July 2011 to October 2012. Data was collected through field notes, structured and non-structured interviews, participant and non-participant observation and focus group discussion. The results show that Mor Lam is a performance style that has been very popular in the Isan region. -

Lukthung Classification Using Neural Networks on Lyrics and Audios

Lukthung Classification Using Neural Networks on Lyrics and Audios Kawisorn Kamtue∗, Kasina Euchukanonchaiy, Dittaya Wanvariez and Naruemon Pratanwanichx ∗yTencent (Thailand) zxDepartment of Mathematics and Computer Science, Faculty of Science, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand Email: ∗[email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Many musical genre classification methods rely heavily on Abstract—Music genre classification is a widely researched audio files, either raw waveforms or frequency spectrograms, topic in music information retrieval (MIR). Being able to as predictors. Previously, traditional approaches focused on automatically tag genres will benefit music streaming service providers such as JOOX, Apple Music, and Spotify for their hand-crafted feature extraction to be input to classifiers [3], content-based recommendation. However, most studies on music [4], while more recent network-based approaches view spec- classification have been done on western songs which differ from trograms as 2-dimensional images for musical genre classifi- Thai songs. Lukthung, a distinctive and long-established type of cation [5]. Thai music, is one of the most popular music genres in Thailand Lyrics-based music classification is less studied, as it has and has a specific group of listeners. In this paper, we develop neural networks to classify such Lukthung genre from others generally been less successful [6]. Early approaches designed using both lyrics and audios. Words used in Lukthung songs lyrics features that were comprised of vocabulary, styles, are particularly poetical, and their musical styles are uniquely semantics, orientations and, structures for SVM classifiers [7]. composed of traditional Thai instruments. We leverage these two Since modern natural language processing techniques have main characteristics by building a lyrics model based on bag-of- switched to recurrent neural networks (RNNs), lyrics-based words (BoW), and an audio model using a convolutional neural network (CNN) architecture. -

10Th Anniversary, College of Music, Mahasarakham University, Thailand

Mahasarakham University International Seminar on Music and the Performing Arts 1 Message from the Dean of College of Music, Mahasarakham University College of Music was originally a division of the Faculty of Fine and Applied Arts that offers a Bachelor of Arts program in Musical Art under the the operation of Western Music, Thai Classical music and Folk Music. The college officially established on September 28, 2007 under the name “College of Music” offering an undergraduate program in musical art as well as master’s and doctoral degree programs. At this 10th anniversary, the College is a host for events such as the international conference and also music and dance workshop from countries who participate and join us. I wish this anniversary cerebration will be useful for scholars from many countries and also students from the colleges and universities in Thailand. I thank everyone who are in charge of this event. Thank you everyone for joining us to cerebrate, support and also enhance our academic knowledge to be shown and shared to everyone. Thank you very much. Best regards, (Khomkrich Karin, Ph.D.) Dean, College of Music Mahasarakham University 10th Anniversary, College of Music, Mahasarakham University, Thailand. 2 November 28 – December 1, 2018 Message from the Director of Kalasin College of Dramatic Arts For the importance of the Tenth Anniversary of the College of Music, Masarakham University. the Kalasin College of Dramatic Arts, Bunditpatanasilpa Institute, feels highly honored to co-host this event This international conference-festival would allow teachers, students and researchers to present and publicize their academic papers in music and dance. -

The Hidden Music of Southeast Asia

THE HIDDEN MUSIC OF SOUTHEAST ASIA Grade Level: Music (8th Grade) Written by: Tommy Reddicks, The Pinnacle Charter School, Federal Heights, CO Length of Unit: Four Lessons of 50 minutes each I. ABSTRACT The roots of music hundreds and thousands of years old are still alive in Southeast Asia today. By exploring musical elements from Thailand, Vietnam, and Indonesia, students will become familiar with new indigenous instruments, musical scales, forms, and styles. They will also gain an understanding and appreciation of non-western musical practices. Students will use combinations of singing, dancing, improvisation, and composition to replicate basic musical forms from each country. II. OVERVIEW A. Concept Objectives 1. Develop an understanding and appreciation of music from various cultures. 2. Learn to recognize indigenous instruments used in music from various cultures. 3. Recognize that literature and art reflect the inner life of a people. B. Content from the Core Knowledge Sequence (CKS) 1. Non-Western Music: Become familiar with scales, instruments, and works from various lands. (page 195) C. Skill Objectives 1. Listen to selected music with varied instrumentation and voicing, and discuss textures and timbres. Derived from the Colorado Standards and Grade Level Expectation for Music (CSGLE) 2. Listen to a musical selection and explain how the composer used specific musical elements. (CSGLE for Music) 3. Read notes in the appropriate clef for the instrument being played. (CSGLE for Music) 4. Read, notate, and perform rhythmic and melodic patterns. (CSGLE for Music) 5. Perform a rhythmic selection of music with syncopation. (CSGLE for Music) III. BACKGROUND KNOWLEDGE A. For Teachers 1. -

Analysis of the Dance of Native Isan Artists for Conservation

Asia Pacific Journal of Multidisciplinary Research, Vol. 3, No. 4, November 2015 Part IV _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Asia Pacific Journal of Analysis of the dance of native Isan artists for Multidisciplinary Research conservation Vol. 3 No. 4, 129-132 November 2015 Part IV Pakawat Petatano, Sithisak Champadaeng and Somkit Suk-Erb P-ISSN 2350-7756 The Faculty of Cultural Science, Mahasarakham University, Khamriang E-ISSN 2350-8442 Sub-District, Kantarawichai District, MahaSarakham Province, Thailand www.apjmr.com [email protected] Date Received: September 28, 2015; Date Revised: October 30, 2015 Abstract –This is a qualitative investigation to analyse native dance in North-eastern Thailand. There were three objectives for this investigation, which were to study the history of Isan folk dance, current dance postures and ways to conserve the current dance postures of Isan folk artists. Research tools were interview, observation, participation, focus group discussion and workshop. The purposively selected research sample was composed of 3 groups of national artists. The findings show that Isan folk dancer shave their own unique dancing styles. Each artist has his or her own identity, which is constructed based on personal experience of dancing and singing. Mor lam is a dance used to accompany traditional Isansung poetry. Modern dance postures have been adapted from the traditional forms. Dance postures have been adapted from three primary sources: traditional literature, the ethnic and Lanchang dancing in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic and rhythmic Khon Kaen compositions. The conclusions of this investigation suggest that preservation of the dancing arts and postures should centre on the incorporation of new knowledge, as well as the continuation of traditional dance postures. -

The Socio-Cultural Capital Management in Lower Northeastern Region, Thailand

European Journal of Molecular & Clinical Medicine ISSN 2515-8260 Volume 7, Issue 8, 2020 THE SOCIO-CULTURAL CAPITAL MANAGEMENT IN LOWER NORTHEASTERN REGION, THAILAND Watcharaporn Jantanukul Faculty of Humanity and Social Science, Ubonrattchathani Rajabhat University, Thailand [email protected] Sanya Kenaphoom* Faculty of Political Science and Public Administration, Rajabhat Maha Sarakham University, Thailand Corresponding Author*, [email protected] Abstract - Socio-cultural capital is a valuable asset because it combines values, beliefs, trust, inclusion, as well as physical assets of wisdom resources which were a good thing in the community, but also to the individual, which if the people in the community realize the value of those assets and help each other to carry on, create value and raise, then take it as a base to think about the direction of the economy in Community or foundation economy, which will affect the strength of the community economy. The objective of this article is to study the status of socio-cultural capital management in the lower Isan area of Thailand. This was the qualitative research, the research sources include (1) the relevant documents and evidence in the research area, and (2) government personnel, folk scholars, business entrepreneurs from cultural products; they were selected by the snowball method for 40 people. The data was analyzed by the content analysis, therefore, the research results found that; The socio-cultural characteristics in the lower Isan region (Lower Northeastern Region), generally, are similar but appearing to have mixed ethnicities especially in Sisaket province which has different cultural, linguistic, and lifestyle characteristics such as dressing, spoken language, food, etc. -

The Effects of Globalization on the Status of Music in Thai Society

The Effects of Globalization on the Status of Music in Thai Society Primrose Maryprasith Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of London Institute of Education 1999 Abstract Globalization tends to be accompanied by two contrary processes: the one a celebration of newly opened international communications, the other, resistance to what is seen as an invasion of foreign culture. This research examines such processes in terms of perceptions of the status of music in Bangkok. The focus is on three main musical categories each of which, if vocal, uses Thai language in its lyrics: Thai classical, Thai country popular and Thai popular music. These musical categories, and the changing relationships between them, are examined in terms of three interconnected areas of perceptions of musical value: the position of music in education, the status of musical careers and the role of music in affirming national identity. Two sets of questionnaires were completed by 100 undergraduate students from 5 universities and 108 secondary-level school music teachers from 108 schools; and interviews were held with 10 respondents from 9 record companies. Whilst the students valued Thai classical music and country popular music as national symbols, they identified themselves with Thai popular music, which has become the main local musical product as a result of the globalization of the music industry. Contrastingly, the teachers understood Thai popular music as a capitulation to foreign culture. They used Thai classical music as the most common extra-curricular activity, but they nonetheless incorporated Thai popular music most often in classrooms. Careers involving Thai classical music were perceived as offering fewer rewards compared to other types of music. -

![Thai Doem [‘Original Thai Song’] Refers to the Large Thai Classical Reper- Tory](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1977/thai-doem-original-thai-song-refers-to-the-large-thai-classical-reper-tory-5421977.webp)

Thai Doem [‘Original Thai Song’] Refers to the Large Thai Classical Reper- Tory

Macquarie University ResearchOnline This is the published version of: Mitchell, James (2011) ‘Red and yellow songs : a historical analysis of the use of music by the United Front for Democracy against Dictatorship (UDD) and the People's Alliance for Democracy (PAD) in Thailand’ South East Asia research, Vol. 19, No. 3, (2011), p.457-494 Access to the published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.5367/sear.2011.0058 Copyright: Copyright c 2011 SOAS. Reproduced by permission of IP Publishing Ltd. Publisher: IP Publishing - http://www.ippublishing.com Red and yellow songs: a historical analysis of the use of music by the United Front for Democracy against Dictatorship (UDD) and the People’s Alliance for Democracy (PAD) in Thailand James Mitchell Abstract: The increase in social protests in Thailand since 2005 has been marked by a dramatic rise in the use of music for protest. This article examines the use of music by the yellow and red shirts, and contextualizes the PAD and UDD within the history of two simi- larly named but very different genres of Thai song: phleng chiwit [life songs] and phleng phuea chiwit [songs for life]. Phleng chiwit was part of a flowering of satirical art forms during Field Marshall Plaek Phibunsongkhram’s second term as Prime Minister (1948– 57) before censorship forced many songwriters to change to the new commercial genre of lukthung [Thai country song]. Phleng phuea chiwit was the preferred music of leftist students in the pro- democracy movement of the 1970s. However, the rehabilitation of phleng phuea chiwit as the official Thai protest genre has disguised the role that lukthung played during the armed struggle of the Com- munist Party of Thailand (CPT). -

Development Model of Lifestyles After the Success of Mor Lam's Career

Asian Social Science; Vol. 10, No. 9; 2014 ISSN 1911-2017 E-ISSN 1911-2025 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Development Model of Lifestyles after the Success of Mor Lam’s Career Supap Tinnarat1, Sitthisak Champadaeng1 & Urarom Chantamala2 1 Faculty of Cultural Science, Mahasarakham University, Maha Sarakham, Thailand 2 Faculty of Fine and Applied Arts, Mahasarakham University, Maha Sarakham, Thailand Correspondence: Supap Tinnarat, Faculty of Cultural Science, Mahasarakham University, Muang District, Maha Sarakham, 44000, Thailand. E-mail: [email protected] Received: June 10, 2013 Accepted: February 28, 2014 Online Published: April 29, 2014 doi:10.5539/ass.v10n9p240 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ass.v10n9p240 Abstract Problem Statement: As northeastern styled singer, or mor lam have a long role to play in society and culture. Mor lam relates to Isan people’s way of life. The objectives of the study were to examine the historical background, the current circumstances and problems of lifestyles and development model of lifestyles after they had achieved highly in career in Isan, Thailand. Approach: The research was carried out in 5 Provinces in Isan or Northeastern Thailand: Khon Kaen, Udon Thani, Ubon Ratchatani, Maha Sarakham, and Roi Et. The instruments used were a basic survey, participant observations, interviews, and focused-group discussions. The 100 informants were key, casual, and general ones respectively. The data analysis was, based on objectives and triangulation technique, done descriptively. Results: Historically, mor lam was basically evolved from four sources: storytelling, exchange of Phaya, soul comforting, and preaching. The storytelling often proceeded with the language of prose and was related to Phaya. -

Youth Identity and Regional Music in Northeastern

YOUTH IDENTITY AND REGIONAL MUSIC IN NORTHEASTERN THAILAND A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAIʻI AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTERS OF ARTS IN MUSIC DECEMBER 2017 by Megan Marie DeKievit Thesis Committee: Frederick Lau, Chairperson Barbara Andaya R. Anderson Sutton Keywords: identity, luk thung, mo lam, urbanization, Isan, Thailand, modernity, globalization, localization, fusion music, luk thung-mo lam Abstract Music in the northeastern region of Thailand comes in several forms, including luk thung, which has been identified by scholars such as Craig Lockhard (1998) and James Mitchell (2015) as the most popular genre of music in Thailand, and mo lam, a local style of singing and dancing mainly performed only in this region. Both these genres trace their origins to Isan, the northeastern region of Thailand, and are strongly associated with the country's Lao minority and rural identity. In the 1990s a new Isan musical genre combining musical characteristics of luk thung and mo lam became popularized throughout Isan and the rest of Thailand. Scholars such as Sanong Klangprasri (2541/1998) and Tinnakorn Attapaiboon (2554/2011) have referred to this genre as luk thung-mo lam. While still firmly situated in the Isan region, this genre has gone through various stylistic changes. Resembling the changing job market of the northeast region, this music is experiencing the effects of urbanization, while still maintaining regional flavor in the sonic effect and sentiment. This study will explore expressions of regional identities in contemporary luk thung-mo lam music as experienced by young people in the Isan region.