Thai Popular Music: the Representation of National Identities and Ideologies Within a Culture in Transition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gmm Grammy Public Company Limited | Annual Report 2013

CONTENTS 20 22 24 34 46 Message from Securities and Management Board of Directors Financial Highlights Chairman and Shareholder Structure and Management Group Chief Information team Executive Officer 48 48 48 50 52 Policy and Business Vision, Mission and Major Changes and Shareholding Revenue Structure Overview Long Term Goal Developments Structure of the and Business Company Group Description 82 85 87 89 154 Risk Factors Management Report on the Board Report of Sub-committee Discussion and of Directors' Independent Report Analysis Responsibility Auditor and towards the Financial Financial Statement Statements 154 156 157 158 159 Audit Committee Risk Management Report of the Report of the Corporate Report Committee Report Nomination and Corporate Governance Remuneration Governance and Committee Ethics Committee 188 189 200 212 214 Internal Control and Connected Corporate Social Details of the General Information Risk Management Transactions Responsibilities Head of Internal and Other Audit and Head Significant of Compliance Information 214 215 220 General Information Companies in which Other Reference Grammy holds more Persons than 10% Please see more of the Company's information from the Annual Registration Statement (Form 56-1) as presented in the www.sec.or.th. or the Company's website 20 ANNUAL REPORT 2013 GMM GRAMMY Mr. Paiboon Damrongchaitham Ms. Boosba Daorueng Chairman of the Board of Directors Group Chief Executive Officer …As one of the leading and largest local content providers, with long-standing experiences, GMM Grammy is confident that our DTT channels will be channels of creativity and quality, and successful. They will be among favorite channels in the mind of viewers nationwide, and can reach viewers in all TV platforms. -

NO. Title Artist Label 1 04.00 the Toys What the Duck 2 ๙

NO. Title Artist Label 1 04.00 The Toys What The Duck 2 ๙ ประกาศิต แสนปากดี (ต่าย อภิรมย์) อิสระ 3 747 PC 0832/676 อิสระ 4 1917 Summer Dress Panda Records 5 1984 Secret Tea Party อิสระ 6 134340 The Photo Sticker Machine feat. ริค วชิรปิลันธน์ อิสระ 7 #ขอโทษจริงๆ Basket Band อิสระ 8 #คนเหงา2018 ปนัสฐ์ นาครําไพ (Point) feat. มารุต ชื�นชมบูรณ์ (Art) SRP 9 #ความรักก็เช่นกัน อภิวัชร์ เอื�อถาวรสุข (Stamp) Love iS 10 #อย่าให้ฉันคิด Room 39 Love is Bec Tero Music 11 (๑) ดูดาว / Stargazing วิมุตติ Bird Sound Record 12 (Intentional) Fall The 10th Saturday Five Four Draft 13 (อย่าทําให้ฉัน) ฝันเก้อ วิตดิวัต พันธุรักษ์ (ต็อง) feat. วินัย พันธุรักษ์ Warner Music 14 ... (Reset) อินธนูและพู่ถุงเท้า Minimal Records 15 … ก่อน Supersub สนามหลวง 16 0.5 sec. PC 0832/676 อิสระ 17 04.00 A.M. Solitude Is Bliss Minimal Records 18 04.00 A.M. [Light Version] Solitude Is Bliss Minimal Records 19 1.9 มิติ Two Million Thanks SO::ON Dry Flower 20 11.15 AM Parim Comet Record 21 12/12 (Once) [No Signal Input 5] Sirimongkol No Signal Input 22 13 ตุลา หนึ�งทุ่มตรง ธเนศ วรากุลนุเคราะห์ อิสระ 23 16090 / หมื�นไมล์ TELEx TELEXs Wayfer Records 24 18+ / สิบแปดบวก Chanudom feat. ธนิดา ธรรมวิมล (ดา Endorphine) What The Duck 25 201.1 KM. สิริพรไฟกิ�ง Summer Disc 26 213 [คณะlพวงlรักlเร่] ประกาศิต แสนปากดี (ต่าย อภิรมย์) อิสระ 27 -30 (Minus Thirty) X0809 อิสระ 28 30 กุมภาพันธ์ / febuary [No Signal Input 5] Sirimongkol No Signal Input 29 30+ แล้วไง? พุทธธิดา ศิระฉายา (อี�ฟ) สหภาพดนตรี 30 ๓๖๐ องศา Sitta อิสระ 31 365 วันกับเครื�องบินกระดาษ BNK48 BNK48 32 3rd Cloud Behind อิสระ 33 4388 (So Long) เจี�ยป้าบ่อสื�อ อิสระ 34 5 O' Clock Away The Ways อิสระ 35 500 กม. -

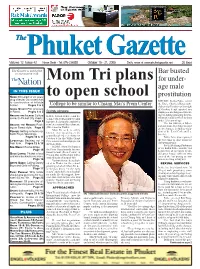

Bar Busted for Under

Volume 12 Issue 42 News Desk - Tel: 076-236555 October 15 - 21, 2005 Daily news at www.phuketgazette.net 20 Baht The Gazette is published in association with Bar busted Mom Tri plans for under- age male IN THIS ISSUE prostitution NEWS: Brit jailed for six years to open school drug offense; Gov orders halt PATONG: Kathu Police raided to construction of hillside College to be similar to Chiang Mai’s Prem Center the Uncle Charlie’s Boys night- homes. Pages 2 & 3 club on Soi Paradise on the night INSIDE STORY: Pier pressure of October 8 and arrested two in Rawai. Pages 4 & 5 By Andy Johnstone employees on charges of procur- AROUND THE ISLAND: Culture KATA: Famed architect and de- ing, including arranging the pro- comes to Phuket City streets. veloper ML Tridhosyuth Devakul vision of sexual services by boys Page 8 has unveiled plans to establish a under 15 years of age. new International Baccalaureate The bar owners, a father- AROUND THE REGION: Rock- and-son team, were later arrested ing on Samui style. Page 9 (IB) school in Phuket. Mom Tri, as he is widely on six charges, including viola- PEOPLE: Getting on famously: known, was speaking at the tions of the Penal Code and La- Keith Floyd; Weddings. bor Act. Pages 10 & 11 groundbreaking ceremony on October 6 for the Villas Grand Police have also requested LIFESTYLE: Backing out in Cru, a new residential project in the Governor to close down the Fein form. Pages 12 & 13 the Kata Hills. club permanently. In 2001, Mom Tri founded Pol Lt Pratuang Pholmana SPA MAGIC: Evolve@Spa. -

Notification of the Central Committee on the Price of Goods and Services No

Notification of the Central Committee on the Price of Goods and Services No. 6, B.E. 2560 (2017) Regarding Control of Transport of Animal Feed Corn ------------------------------------ Whereas the Central Committee on the Price of Goods and Services has repealed the Notification of the Central Committee on the Price of Goods and Services No. 1, B.E. 2559 (2016) regarding Determination of Goods and Services under Control dated 21 January B.E. 2559 ( 2016) , resulting in the end of enforcement of the Notification of the Central Committee on the Price of Goods and Services No. 6, B.E. 2559 (2016) regarding Control of Transport of Animal Feed dated 25 January B.E. 2559 (2016). In the meantime, the Central Committee on the Price of Goods and Services has already reconsidered the exercise of its power regarding the stipulation of the aforesaid measure, it is of the view that the measure of the control of transport of animal feed corn should be maintained in order to bring about the fairness of price, quantity and the maintenance of stability of the animal feed market system within the Kingdom. By virtue of Section 9 (2) and Section 25 (4), (7) of the Price of Goods and Services Act, B.E. 2542 ( 1999) , the Central Committee on the Price of Goods and Services has therefore issued this Notification, as follows. Article 1. This Notification shall come into force in all areas of the Kingdom for the period of one year as from the day following the date of its publication.1 Article 2. It is prohibited for a person to transport animal feed corn, whereby -

Song List 2012

SONG LIST 2012 www.ultimamusic.com.au [email protected] (03) 9942 8391 / 1800 985 892 Ultima Music SONG LIST Contents Genre | Page 2012…………3-7 2011…………8-15 2010…………16-25 2000’s…………26-94 1990’s…………95-114 1980’s…………115-132 1970’s…………133-149 1960’s…………150-160 1950’s…………161-163 House, Dance & Electro…………164-172 Background Music…………173 2 Ultima Music Song List – 2012 Artist Title 360 ft. Gossling Boys Like You □ Adele Rolling In The Deep (Avicii Remix) □ Adele Rolling In The Deep (Dan Clare Club Mix) □ Afrojack Lionheart (Delicious Layzas Moombahton) □ Akon Angel □ Alyssa Reid ft. Jump Smokers Alone Again □ Avicii Levels (Skrillex Remix) □ Azealia Banks 212 □ Bassnectar Timestretch □ Beatgrinder feat. Udachi & Short Stories Stumble □ Benny Benassi & Pitbull ft. Alex Saidac Put It On Me (Original mix) □ Big Chocolate American Head □ Big Chocolate B--ches On My Money □ Big Chocolate Eye This Way (Electro) □ Big Chocolate Next Level Sh-- □ Big Chocolate Praise 2011 □ Big Chocolate Stuck Up F--k Up □ Big Chocolate This Is Friday □ Big Sean ft. Nicki Minaj Dance Ass (Remix) □ Bob Sinclair ft. Pitbull, Dragonfly & Fatman Scoop Rock the Boat □ Bruno Mars Count On Me □ Bruno Mars Our First Time □ Bruno Mars ft. Cee Lo Green & B.O.B The Other Side □ Bruno Mars Turn Around □ Calvin Harris ft. Ne-Yo Let's Go □ Carly Rae Jepsen Call Me Maybe □ Chasing Shadows Ill □ Chris Brown Turn Up The Music □ Clinton Sparks Sucks To Be You (Disco Fries Remix Dirty) □ Cody Simpson ft. Flo Rida iYiYi □ Cover Drive Twilight □ Datsik & Kill The Noise Lightspeed □ Datsik Feat. -

Deborah's M.A Thesis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarBank@NUS Created in its own sound: Hearing Identity in The Thai Cinematic Soundtrack Deborah Lee National University of Singapore 2009 Acknowledgements Heartfelt thanks goes out to the many people that have helped to bring this thesis into fruition. Among them include the many film-composers, musicians, friends, teachers and my supervisors (both formal and informal) who have contributed so generously with their time and insights. Professor Rey, Professor Goh, Prof Irving, Prof Jan, Aajaarn Titima, Aajaarn Koong, Aajaarn Pattana, I really appreciate the time you took and the numerous, countless ways in which you have encouraged me and helped me in the process of writing this thesis. Pitra and Aur, thank you for being such great classmates. The articles you recommended and insights you shared have been invaluable to me in the research and writing of my thesis. Rohani, thanks for facilitating all the administrative details making my life as a student so much easier. Chatchai, I’ve been encouraged and inspired by you. Thank you for sharing so generously of your time and love for music. Oradol, thank you so much for the times we have had together talking about Thai movies and music. I’ve truly enjoyed our conversations. There are so many other people that have contributed in one way or the other to the successful completion of this thesis. The list goes on and on, but unfortunately I am running out of time and words…. Finally, I would like to thank God and acknowledge His grace that has seen me through in the two years of my Masters program in the Department of Southeast Asian Studies. -

Sub Total Revenue

Grand Millennium Sukhumvit Hotel November 14, 2014 www.gmmgrammy.com Forward-Looking Statements This presentation was made from the analysis of reliable information in order to assist investment community to better understand the company's financial status and operation. The presentation may contain forward-looking statements and comments on future events, including our expectation about GMM Grammy’s business. However, the information within this presentation has been derived from the existing factors in the present time. Therefore, the forward-looking information on this presentation may not occur in the future if the aforementioned factors or situations are changed. Investors are, however, required to use their own discretion regarding the use of information contained in this presentation for any purpose. For further information, please contact Investor Relations of GMM Grammy Public Company Limited at Tel: (662) 669-9936, (662) 669-9952, (662) 669 9729 or Email : [email protected] www.gmmgrammy.com 1 Agenda » 3Q14 Financial Highlight » Our Winning Strategy » DTV Regulatory Update » Q & A www.gmmgrammy.com 2 3Q14 Financial Highlight 3 Business Overview GMM Grammy is a leader in fully integrated media and unique entertainment platform in Thailand who can produce and deliver high quality local contents and expand into the region GMM Grammy Business comprise: Core Business Other Businesses o Music o Media (Free TV, Radio, Publishing) o Digital Terrestrial TV o Movie o One channel o Event Management o GMM channel o Home Shopping TV o Satellite TV www.gmmgrammy.com 4 9M14 Financial Performance By Type of Business (THB mm) By Type of Business (%) 11,756 11,004 9,388 2,834 24% 24% 2,961 27% 31% 2,214 2,101 7,282 6% 1,563 18% 14% 570 18% 2,233 32% 3,246 3,017 3,395 28% 31% 1,340 25% 1,853 3,587 3,575 38% 3,084 30% 28% 25% 1,855 2011 2012 2013 9M14 2011 2012 2013 9M14 Music Business Media Business (Incl. -

The Lao in Sydney

Sydney Journal 2(2) June 2010 ISSN 1835-0151 http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/ojs/index.php/sydney_journal/index The Lao in Sydney Ashley Carruthers Phouvanh Meuansanith The Lao community of Sydney is small and close-knit, and concentrated in the outer southwest of the city. Lao refugees started to come to Australia following the takeover by the communist Pathet Lao in 1975, an event that caused some 10 per cent of the population to flee the country. The majority of the refugees fled across the Mekong River into Thailand, where they suffered difficult conditions in refugee camps, sometimes for years, before being resettled in Australia. Lao Australians have managed to rebuild a strong sense of community in western Sydney, and have succeeded in establishing two major Theravada Buddhist temples that are foci of community life. Lao settlement in south-western Sydney There are some 5,551 people of Lao ancestry resident in Sydney according to the 2006 census, just over half of the Lao in Australia (10,769 by the 2006 census). The largest community is in the Fairfield local government area (1,984), followed by Liverpool (1,486) and Campbelltown (1,053). Like the Vietnamese, Lao refugees were initially settled in migrant hostels in the Fairfield area, and many stayed and bought houses in this part of Sydney. Fairfield and its surrounding suburbs offered affordable housing and proximity to western Sydney's manufacturing sector, where many Lao arrivals found their first jobs and worked until retirement. Cabramatta and Fairfield also offer Lao people resources such as Lao grocery stores and restaurants, and the temple in Edensor Park is nearby. -

English Song Booklet

English Song Booklet SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER 100002 1 & 1 BEYONCE 100003 10 SECONDS JAZMINE SULLIVAN 100007 18 INCHES LAUREN ALAINA 100008 19 AND CRAZY BOMSHEL 100012 2 IN THE MORNING 100013 2 REASONS TREY SONGZ,TI 100014 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 100015 2012 IT AIN'T THE END JAY SEAN,NICKI MINAJ 100017 2012PRADA ENGLISH DJ 100018 21 GUNS GREEN DAY 100019 21 QUESTIONS 5 CENT 100021 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN GREEN DAY 100022 21ST CENTURY GIRL WILLOW SMITH 100023 22 (ORIGINAL) TAYLOR SWIFT 100027 25 MINUTES 100028 2PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 100030 3 WAY LADY GAGA 100031 365 DAYS ZZ WARD 100033 3AM MATCHBOX 2 100035 4 MINUTES MADONNA,JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 100034 4 MINUTES(LIVE) MADONNA 100036 4 MY TOWN LIL WAYNE,DRAKE 100037 40 DAYS BLESSTHEFALL 100038 455 ROCKET KATHY MATTEA 100039 4EVER THE VERONICAS 100040 4H55 (REMIX) LYNDA TRANG DAI 100043 4TH OF JULY KELIS 100042 4TH OF JULY BRIAN MCKNIGHT 100041 4TH OF JULY FIREWORKS KELIS 100044 5 O'CLOCK T PAIN 100046 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100045 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100047 6 FOOT 7 FOOT LIL WAYNE 100048 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVID 100049 7 THINGS MILEY CYRUS 100050 9 PIECE RICK ROSS,LIL WAYNE 100051 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ 100052 A BABY CHANGES EVERYTHING FAITH HILL 100053 A BEAUTIFUL LIE 3 SECONDS TO MARS 100054 A DIFFERENT CORNER GEORGE MICHAEL 100055 A DIFFERENT SIDE OF ME ALLSTAR WEEKEND 100056 A FACE LIKE THAT PET SHOP BOYS 100057 A HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS LADY ANTEBELLUM 500164 A KIND OF HUSH HERMAN'S HERMITS 500165 A KISS IS A TERRIBLE THING (TO WASTE) MEAT LOAF 500166 A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON LOUIS ARMSTRONG 100058 A KISS WITH A FIST FLORENCE 100059 A LIGHT THAT NEVER COMES LINKIN PARK 500167 A LITTLE BIT LONGER JONAS BROTHERS 500168 A LITTLE BIT ME, A LITTLE BIT YOU THE MONKEES 500170 A LITTLE BIT MORE DR. -

Download in English

DDrraafftteedd 22000088 AAvian and Human Influenza Pandemic Preparedness Plan in 4 Piloted Districts of Chiang Rai Province, Thailand The Migrant Health Project in Chiang Rai Province A Collaboration between the Ministry of Public Health and the International Public Health and the International Organization for Migration, Thailand a DDrraafftteedd 22000088 AAvian and Human Influenza Pandemic Preparedness Plan in 4 Piloted Districts of Chiang Rai Province, Thailand The Migrant Health Project in Chiang Rai Province A Collaboration between the Ministry of Public Health and the International Organization for Migration, Thailand b Title : Draft of Avian and Human Influenza Pandemic Preparedness Plan in 4 Pilot Districts, Chiang Rai Province, Thailand in 2008 Advisers : Dr. Surin Sumnaphan : Dr. Nigoon Jitthai : Ms. Ratchanee Buranakitpibul Editorial Team : Dr. Nigoon Jitthai Dr. Sushera Bunluesin Mr. Vittaya Sumitmoh Ms. Lissa Giurissevich Publisher : International Organization for Migration (IOM) Graphic Design : Mr. Manit Kaewkunta Published Date : 1st Edition , May 2009 Copies : 300 Printer : Baan Copy Center, 132/13, Moo 4, Ban Doo Sub-district, Muang District, Chiang Rai Province, 57100 Tel: 053-776-432 c PPrreeffaaccee Poultry influenza or Human influenza type H5N1 has spread in many parts of the world since 2003. A large number of poultry has been infected with H5N1 in Thailand, in addition to disease, ill health and mortality experienced in human cases infected with H5N1. These cases are the cause for significant concerns about the H5N1 strain and its potential impact on the social and economical environment. Therefore, the Migrant Health Project in Chiang Rai Province, a collaboration between the Ministry of Public Health and the International Organization for Migration Thailand, have taken steps to raise awareness about Avian and Human Influenza pandemic preparedness. -

Kd Lagu Judul Lagu Penyanyi Mark

By Titles # Harga @lagu hanya Rp.1000,- # Minimal 100 lagu, 500 lagu bonus SOFTWARE YEN-KARAOKE # Format file DAT/MPEG # Paket : DVD # Pembayaran Via Transfer Bank Mandiri No.Rek. 156-00-0223716-4 A/n Yendry # Pengiriman Via jasa JNE # Contact : Yendry 0812 50000 150 Beri tanda 1 pada kolom Mark untuk lagu pilihan Kirim xls ini kembali ke [email protected] bila anda memesan lagu2 karaoke berikut ini Kd_Lagu Judul_Lagu Penyanyi Mark E-0001 1 2 3 4 PLAIN WHITE TS Total lagu yg dip E-0002 1+1=CINTA BROERY PESOLIMA E-0003 100% PURE LOVE CRYSTAL WATER E-0004 1000 STARS NATALIE BASSINGTHWAIGTHE Harga E-0005 12 STEP CLARA FEAT MISSY ELLIOT E-0006 123 WHITNEY HOUSTON E-0007 18 TILL I DIE NN BARAT E-0008 1973 JAMES BLUNT E-0009 1999 PRINCE E-0010 21 GUNS GREEN DAY E-0011 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN GREEN DAY E-0012 25 MINUTES MLTR E-0013 25 OR 6 TO 4 NN BARAT E-0014 3 WORDS CHERYL COLE AND WILL I AM E-0015 3 BRITNEY SPEARS E-0016 30 SECONDS TO MARS A BEAUTIFUL LIE E-0017 4 EVER THE VERONICAS E-0018 4 MINUTES MADONNA FEAT JUSTIN E-0019 500 MILES AWAY FROM HOME PETER PAUL AND MARY E-0020 500 MILES PETER PAUL AND MARY E-0021 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVIDS E-0022 7 SECONDS YOUSSON NDOUR E-0023 7 THINGS MILEY CYRUS E-0024 7 YEARS AND 50 DAYS GROOVE COVERAGE E-0025 7 PRINCE E-0026 9 TO 5 DOLLY PARTON E-0027 A BETTER LOVE NEXT TIME JOHNNY CHRISTOPHER E-0028 A BETTER MAN NN BARAT E-0029 A BLOSSOM FELL NAT KING COLE E-0030 A CERTAIN KIND NN BARAT E-0031 A CERTAIN SMILE NN BARAT E-0032 A DEAR JOHN LETTER SKEETER DAVIDS E-0033 A DIFFERENT BEAT BOYZONE E-0034 A DIFFERENT -

Asia by Robert Casteels

Resonances k: of Asia by Robert Casteels LIBRARYBOARD NATION All Rights Reserved, National Library Board, Singapore - Resonances k Recording locations and year: Track 1 and 12: Parekh Recording Centre, Bangalore, India 2007/ Track 2 and 8: Gopal Raj of recording, LASALLE College of the Arts, Singapore November 2009/ Track 3: School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London 2006/ Track 4, 9, 10 and 13: Pavane Recording Studio, Singapore December 2009/ Track 5: Rolton recording, National University of Singapore, University Cultural Hall, Singapore 2002/ Track 6: Manuel Cabrera II recording, Singapore November 2009/ Asia Track 7 and 11: Huy Oestrom Moeller recording, Singapore 2003 Robert Copyright and permission: Track 1 and 12: Ghanavenotham Retnam/ Track 3: Paphutsorn by Casteels Wongratanapitak/ Track 2, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 10 and 13: Robert Casteels/ Track 7 and 11: Huy Oestrom Moeller Mastering: Pavane Recording Studio, Singapore Author of programme notes: Dr Robert Casteels Initiator and coordinator of the CD project: Didier Ballenghien, CIC Singapore Branch Coordination of the CD design: Rose Teo‘ CIC Singapore Branch Photographer: Russel Wong Text editor: Jolie Giouw Graphic Designer: Dunhill Von Gonzales, Creative Studio Xpress Printer: Xpress Print Pte Ltd & ® 2009 All rights reserved C C All Rights Reserved, National Library Board, Singapore Foreword Resonances of Asia by Robert Casteels Music is high on CIC agenda of sponsoring throughout the world. 1 Alaipayyuthe [7:40] Composed by Oothukkadu Vegadasubbaiar for Khuzal and ensemble of South Indian instruments In France, Crédit Industriel et Commercial has been sponsoring the annual classical music awards “Ies Victoires de la Musique" for numerous years and is the privileged 2 Baris [4:02] Balinese warrior dance for Gamelan orchestra sponsor and owner of a famous cello made in 1737 by Francesco Goffriller and played by internationally renowned cellist Ophélie Gaillard, (www.0pheliegaillard.com).