Thai Doem [‘Original Thai Song’] Refers to the Large Thai Classical Reper- Tory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thailand's Red Networks: from Street Forces to Eminent Civil Society

Southeast Asian Studies at the University of Freiburg (Germany) Occasional Paper Series www.southeastasianstudies.uni-freiburg.de Occasional Paper N° 14 (April 2013) Thailand’s Red Networks: From Street Forces to Eminent Civil Society Coalitions Pavin Chachavalpongpun (Kyoto University) Pavin Chachavalpongpun (Kyoto University)* Series Editors Jürgen Rüland, Judith Schlehe, Günther Schulze, Sabine Dabringhaus, Stefan Seitz The emergence of the red shirt coalitions was a result of the development in Thai politics during the past decades. They are the first real mass movement that Thailand has ever produced due to their approach of directly involving the grassroots population while campaigning for a larger political space for the underclass at a national level, thus being projected as a potential danger to the old power structure. The prolonged protests of the red shirt movement has exceeded all expectations and defied all the expressions of contempt against them by the Thai urban elite. This paper argues that the modern Thai political system is best viewed as a place dominated by the elite who were never radically threatened ‘from below’ and that the red shirt movement has been a challenge from bottom-up. Following this argument, it seeks to codify the transforming dynamism of a complicated set of political processes and actors in Thailand, while investigating the rise of the red shirt movement as a catalyst in such transformation. Thailand, Red shirts, Civil Society Organizations, Thaksin Shinawatra, Network Monarchy, United Front for Democracy against Dictatorship, Lèse-majesté Law Please do not quote or cite without permission of the author. Comments are very welcome. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the author in the first instance. -

Thailand White Paper

THE BANGKOK MASSACRES: A CALL FOR ACCOUNTABILITY ―A White Paper by Amsterdam & Peroff LLP EXECUTIVE SUMMARY For four years, the people of Thailand have been the victims of a systematic and unrelenting assault on their most fundamental right — the right to self-determination through genuine elections based on the will of the people. The assault against democracy was launched with the planning and execution of a military coup d’état in 2006. In collaboration with members of the Privy Council, Thai military generals overthrew the popularly elected, democratic government of Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, whose Thai Rak Thai party had won three consecutive national elections in 2001, 2005 and 2006. The 2006 military coup marked the beginning of an attempt to restore the hegemony of Thailand’s old moneyed elites, military generals, high-ranking civil servants, and royal advisors (the “Establishment”) through the annihilation of an electoral force that had come to present a major, historical challenge to their power. The regime put in place by the coup hijacked the institutions of government, dissolved Thai Rak Thai and banned its leaders from political participation for five years. When the successor to Thai Rak Thai managed to win the next national election in late 2007, an ad hoc court consisting of judges hand-picked by the coup-makers dissolved that party as well, allowing Abhisit Vejjajiva’s rise to the Prime Minister’s office. Abhisit’s administration, however, has since been forced to impose an array of repressive measures to maintain its illegitimate grip and quash the democratic movement that sprung up as a reaction to the 2006 military coup as well as the 2008 “judicial coups.” Among other things, the government blocked some 50,000 web sites, shut down the opposition’s satellite television station, and incarcerated a record number of people under Thailand’s infamous lèse-majesté legislation and the equally draconian Computer Crimes Act. -

Download This PDF File

“PM STANDS ON HIS CRIPPLED LEGITINACY“ Wandah Waenawea CONCEPTS Political legitimacy:1 The foundation of such governmental power as is exercised both with a consciousness on the government’s part that it has a right to govern and with some recognition by the governed of that right. Political power:2 Is a type of power held by a group in a society which allows administration of some or all of public resources, including labor, and wealth. There are many ways to obtain possession of such power. Demonstration:3 Is a form of nonviolent action by groups of people in favor of a political or other cause, normally consisting of walking in a march and a meeting (rally) to hear speakers. Actions such as blockades and sit-ins may also be referred to as demonstrations. A political rally or protest Red shirt: The term5inology and the symbol of protester (The government of Abbhisit Wejjajiva). 1 Sternberger, Dolf “Legitimacy” in International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences (ed. D.L. Sills) Vol. 9 (p. 244) New York: Macmillan, 1968 2 I.C. MacMillan (1978) Strategy Formulation: political concepts, St Paul, MN, West Publishing; 3 Oxford English Dictionary Volume 1 | Number 1 | January-June 2013 15 Yellow shirt: The terminology and the symbol of protester (The government of Thaksin Shinawat). Political crisis:4 Is any unstable and dangerous social situation regarding economic, military, personal, political, or societal affairs, especially one involving an impending abrupt change. More loosely, it is a term meaning ‘a testing time’ or ‘emergency event. CHAPTER I A. Background Since 2008, there has been an ongoing political crisis in Thailand in form of a conflict between thePeople’s Alliance for Democracy (PAD) and the People’s Power Party (PPP) governments of Prime Ministers Samak Sundaravej and Somchai Wongsawat, respectively, and later between the Democrat Party government of Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva and the National United Front of Democracy Against Dictatorship (UDD). -

The 1960S Thai Pop Music and Bangkok Youth Culture

Rebel without Causes: The 1960s Thai Pop Music and Bangkok Youth Culture Viriya Sawangchot Mahidol University E-mail: [email protected] Abstract In this paper, I would like to acknowledge that 1960s to the 1970s American popular culture, particularly in rock ‘n’ roll music, have Been contested By Thai context. In term oF this, the paper intends to consider American rock ’n’ roll has come to Function as a mode oF humanization and emancipation oF Bangkok youngster rather than ideological domination. In order to understand this process, this paper aims to Focus on the origins and evolution oF rock ‘n’ roll and youth culture in Bangkok in the 1960s to 1970s. The Birth of pleng shadow and pleng string will be discussed in this context as well. Keywords: Thai Pop Music, Bangkok Youth Culture, ideological domination 1 Rebel without Causes: The 1960s Thai Pop Music and Bangkok Youth Culture Viriya Sawangchot Introduction In Thailand, the Cold War and Modernization era began with the Coup of 1958 which led by Field-Marshall Sarit Tanarat. ConseQuently, the modernizing state run By military junta, the Sarit regime (1958-1964) and his coup colleague, Field –Marshall Thanom Kittikajon (1964 -1973), has done many things such as education, development and communication, with strongly supported By U.S. Cold War policy and Thai elite incorporating the new landscape politico-cultural power with regardless to the issues oF democracy, human rights, and social justice(Chaloemtiarana 1983). The American Cold war’s polices also contriButed to increasing capital Flow in Thailand, which also meant increasing the gloBal cultural Flow and the educational rate( Phongpaichai and Baker1997). -

Deborah's M.A Thesis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarBank@NUS Created in its own sound: Hearing Identity in The Thai Cinematic Soundtrack Deborah Lee National University of Singapore 2009 Acknowledgements Heartfelt thanks goes out to the many people that have helped to bring this thesis into fruition. Among them include the many film-composers, musicians, friends, teachers and my supervisors (both formal and informal) who have contributed so generously with their time and insights. Professor Rey, Professor Goh, Prof Irving, Prof Jan, Aajaarn Titima, Aajaarn Koong, Aajaarn Pattana, I really appreciate the time you took and the numerous, countless ways in which you have encouraged me and helped me in the process of writing this thesis. Pitra and Aur, thank you for being such great classmates. The articles you recommended and insights you shared have been invaluable to me in the research and writing of my thesis. Rohani, thanks for facilitating all the administrative details making my life as a student so much easier. Chatchai, I’ve been encouraged and inspired by you. Thank you for sharing so generously of your time and love for music. Oradol, thank you so much for the times we have had together talking about Thai movies and music. I’ve truly enjoyed our conversations. There are so many other people that have contributed in one way or the other to the successful completion of this thesis. The list goes on and on, but unfortunately I am running out of time and words…. Finally, I would like to thank God and acknowledge His grace that has seen me through in the two years of my Masters program in the Department of Southeast Asian Studies. -

Thai Freedom and Internet Culture 2011

Thai Netizen Network Annual Report: Thai Freedom and Internet Culture 2011 An annual report of Thai Netizen Network includes information, analysis, and statement of Thai Netizen Network on rights, freedom, participation in policy, and Thai internet culture in 2011. Researcher : Thaweeporn Kummetha Assistant researcher : Tewarit Maneechai and Nopphawhan Techasanee Consultant : Arthit Suriyawongkul Proofreader : Jiranan Hanthamrongwit Accounting : Pichate Yingkiattikun, Suppanat Toongkaburana Original Thai book : February 2012 first published English translation : August 2013 first published Publisher : Thai Netizen Network 672/50-52 Charoen Krung 28, Bangrak, Bangkok 10500 Thailand Thainetizen.org Sponsor : Heinrich Böll Foundation 75 Soi Sukhumvit 53 (Paidee-Madee) North Klongton, Wattana, Bangkok 10110, Thailand The editor would like to thank you the following individuals for information, advice, and help throughout the process: Wason Liwlompaisan, Arthit Suriyawongkul, Jiranan Hanthamrongwit, Yingcheep Atchanont, Pichate Yingkiattikun, Mutita Chuachang, Pravit Rojanaphruk, Isriya Paireepairit, and Jon Russell Comments and analysis in this report are those of the authors and may not reflect opinion of the Thai Netizen Network which will be stated clearly Table of Contents Glossary and Abbreviations 4 1. Freedom of Expression on the Internet 7 1.1 Cases involving the Computer Crime Act 7 1.2 Internet Censorship in Thailand 46 2. Internet Culture 59 2.1 People’s Use of Social Networks 59 in Political Movements 2.2 Politicians’ Use of Social -

Cultural Landscape and Indigenous Knowledge of Natural Resource and Environment Management of Phutai Tribe

CULTURAL LANDSCAPE AND INDIGENOUS KNOWLEDGE OF NATURAL RESOURCE AND ENVIRONMENT MANAGEMENT OF PHUTAI TRIBE By Mr. Isara In-ya A Thesis Submitted in Partial of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Architectural Heritage Management and Tourism International Program Graduate School, Silpakorn University Academic Year 2014 Copyright of Graduate School, Silpakorn University CULTURAL LANDSCAPE AND INDIGENOUS KNOWLEDGE OF NATURAL RESOURCE AND ENVIRONMENT MANAGEMENT OF PHUTAI TRIBE By Mr. Isara In-ya A Thesis Submitted in Partial of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Architectural Heritage Management and Tourism International Program Graduate School, Silpakorn University Academic Year 2014 Copyright of Graduate School, Silpakorn University The Graduate School, Silpakorn University has approved and accredited the Thesis title of “Cultural landscape and Indigenous Knowledge of Natural Resource and Environment Management of Phutai Tribe” submitted by Mr.Isara In-ya as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architectural Heritage Management and Tourism. …………………………………………………………... (Associate Professor Panjai Tantatsanawong, Ph.D.) Dean of Graduate School ……..……./………..…./…..………. The Thesis Advisor Professor Ken Taylor The Thesis Examination Committee …………………………………………Chairman (Associate Professor Chaiyasit Dankittikul, Ph.D.) …………../...................../................. …………………………………………Member (Emeritus Professor Ornsiri Panin) …………../...................../................ -

The Lao in Sydney

Sydney Journal 2(2) June 2010 ISSN 1835-0151 http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/ojs/index.php/sydney_journal/index The Lao in Sydney Ashley Carruthers Phouvanh Meuansanith The Lao community of Sydney is small and close-knit, and concentrated in the outer southwest of the city. Lao refugees started to come to Australia following the takeover by the communist Pathet Lao in 1975, an event that caused some 10 per cent of the population to flee the country. The majority of the refugees fled across the Mekong River into Thailand, where they suffered difficult conditions in refugee camps, sometimes for years, before being resettled in Australia. Lao Australians have managed to rebuild a strong sense of community in western Sydney, and have succeeded in establishing two major Theravada Buddhist temples that are foci of community life. Lao settlement in south-western Sydney There are some 5,551 people of Lao ancestry resident in Sydney according to the 2006 census, just over half of the Lao in Australia (10,769 by the 2006 census). The largest community is in the Fairfield local government area (1,984), followed by Liverpool (1,486) and Campbelltown (1,053). Like the Vietnamese, Lao refugees were initially settled in migrant hostels in the Fairfield area, and many stayed and bought houses in this part of Sydney. Fairfield and its surrounding suburbs offered affordable housing and proximity to western Sydney's manufacturing sector, where many Lao arrivals found their first jobs and worked until retirement. Cabramatta and Fairfield also offer Lao people resources such as Lao grocery stores and restaurants, and the temple in Edensor Park is nearby. -

Dutch Pop Music Is Here to Stay

DUTCH POP MUSIC IS HERE TO STAY Continuïteit en vernieuwing van het aanbod van Nederlandse popmuziek 1960-1990 Olivier van der Vet Uitgever: ERMeCC, Erasmus Research Centre for Media, Communication and Culture Drukker: Ridderprint Ridderkerk Omslagontwerp: Nikki Vermeulen Ridderprint ISBN: 978-90-76665-24-5 © Olivier van der Vet, 2013 DUTCH POP MUSIC IS HERE TO STAY: Continuïteit en vernieuwing van het aanbod van Nederlandse popmuziek 1960-1990 Dutch Pop Music Is Here To Stay: Continuity and Innovation of Dutch Pop Music between 1960-1990 Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam op gezag van de rector magnificus Prof.dr. H.G. Schmidt en volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties. De openbare verdediging zal plaatsvinden op donderdag, 16 mei 2013 om 15.30 uur door Olivier Nicolo Sebastiaan van der Vet geboren te ‘s-Gravenhage Promotiecommissie: Promotor: Prof. dr. A.M. Bevers Overige leden: Prof. dr. C.J.M van Eijck Prof. dr. G. De Meyer Prof. dr. P.W.M. Rutten Copromotor: Dr. W. de Nooy VOORWOORD Continuïteit en vernieuwing zijn de twee termen die in dit onderzoek centraal staan. Nederlandse artiesten zijn op zoek naar continuïteit in hun loopbaan en platenmaatschappijen naar continuïteit in de productie. In dit streven vinden zij elkaar en ontstaat het aanbod. Continuïteit stond ook centraal in het traject dat ik heb afgelegd voor dit promotieonderzoek. Vanaf de start, toen ik als onderzoeker bij het Erasmus Centrum voor Kunst- en Cultuurwetenschappen (ECKCW) werkte, tot nu, is het promotieonderzoek een constante factor geweest. Wat er in deze periode ook is veranderd, het promotieonderzoek bleef. -

(Title of the Thesis)*

University of Huddersfield Repository Treewai, Pichet Political Economy of Media Development and Management of the Media in Bangkok Original Citation Treewai, Pichet (2015) Political Economy of Media Development and Management of the Media in Bangkok. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/26449/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ POLITICAL ECONOMY OF MEDIA DEVELOPMENT AND MANAGEMENT OF THE MEDIA IN BANGKOK PICHET TREEWAI A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Strategy, Marketing and Economics The University of Huddersfield March 2015 Abstract This study is important due to the crucial role of media in the dissemination of information, especially in emerging economies, such as Thailand. -

2588Booklet.Pdf

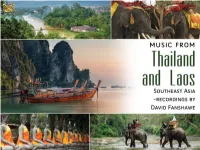

ENGLISH P. 2 DEUTSCH S. 8 MUSIC FROM THAILAND AND LAOS SOUTHEAST ASIA – RECORDINGS BY DAVID FANSHAWE DAVID FANSHAWE David Fanshawe was a composer, ethnic sound recordist, guest speaker, photographer, TV personality, and a Churchill Fellow. He was born in 1942 in Devon, England and was educated at St. George’s Choir School and Stowe, after which he joined a documentary film company. In 1965 he won a Foundation Scholarship to the Royal College of Music in London. His ambition to record indigenous folk music began in the Middle East in 1966, and was intensified on subsequent journeys through North and East Africa (1969 – 75) resulting in his unique and highly original blend of Music and Travel. His work has been the subject of BBC TV documentaries including: African Sanctus, Arabian Fantasy, Musical Mariner (National Geographic) and Tropical Beat. Compositions include his acclaimed choral work African Sanctus; also Dona nobis pacem – A Hymn for World Peace, Sea Images, Dover Castle, The Awakening, Serenata, Fanfare to Planet Earth / Millennium March. He has also scored many film and TV productions including Rank’s Tarka the Otter, BBC’s When the Boat Comes In and ITV’s Flambards. Since 1978, his ten years of research in the Pacific have resulted in a monumental archive, documenting the music and oral traditions of Polynesia, Micronesia and Melanesia. David has three children, Alexander and Rebecca with his first wife Judith; and Rachel with his second wife Jane. David was awarded an Honorary Degree of Doctor of Music from the University of the West of England (UWE) in 2009. -

The Khaen: Place, Power, Permission, and Performance

THE KHAEN: PLACE, POWER, PERMISSION, AND PERFORMANCE by Anne Greenwood B.Mus., The University of British Columbia, 2011 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in The Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies (Ethnomusicology) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA Vancouver June 2016 © Anne Greenwood, 2016 Abstract While living in the Isan region of Thailand I had the opportunity to start learning the traditional wind instrument the khaen (in Thai, แคน, also transliterated as khène). This thesis outlines the combination of methods that has allowed me to continue to play while tackling broader questions surrounding permission and place that arise when musicians, dancers, or artists work with materials from other cultures. Through an examination of the geographical, historical, and social contexts of the Isan region I have organized my research around the central themes of place, power, permission, and performance. My intent is to validate the process of knowledge acquisition and the value of what one has learned through action, specifically musical performance, and to properly situate such action within contemporary practice where it can contribute to the development and continuation of an endangered art form. ii Preface This thesis is original, unpublished, independent work by the author, Anne Greenwood. iii Table of Contents Abstract .......................................................................................................................................... ii Preface