The Khaen: Place, Power, Permission, and Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Laos, Known As the “Land of a Million Elephants,” Is a Landlocked Country in Southeast Asia About the Size of Kansas

DO NOT COPY WITHOUT PERMISSION OF AUTHOR Simon J. Bronner, ed. ENCYCLOPEDIA OF AMERICAN FOLKLIFE. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2005. Rachelle H. Saltzman, Iowa Arts Council, Iowa Department of Cultural Affairs [email protected] LAO Laos, known as the “Land of a Million Elephants,” is a landlocked country in Southeast Asia about the size of Kansas. The elephant symbolizes the ancient kingdom of Lan Xang, and is sacred to the Lao people, who believe it will bring prosperity to their country. Bordered by China to the north, Vietnam to the east, Cambodia to the south, Thailand to the west, and Myanmar (formerly Burma) to the northwest, Laos is a rough and mountainous land interwoven with forests and plateaus. The Mekong River, which runs through the length of Laos and supplies water to the fertile plains of the river basin, is both symbolically and practically, the lifeline of the Lao people, who number nearly 6 million. According to Wayne Johnson, Chief for the Iowa Bureau of Refugee Services, and a former Peace Corps Volunteer, “the river has deep meaning for the ethnic Lao who are Buddhist because of the intrinsic connection of water with the Buddhist religion, a connection that does not exist for the portion of the population who are non-ethnically Lao and who are animists.” Formally known as the Kingdom of Laos, and now known as Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Laos was, in previous centuries, periodically independent and periodically part of the Khmer (Cambodian), Mongol, Vietnamese, and Thai (Siamese) empires. Lao, Thai, and Khmer (but not Vietnamese) share a common heritage evident today in similar religion, music, food, and dance traditions as well as language and dress. -

Composition Inspired by ASEAN Drums: Sakodai

Volume 21, 2020 – Journal of Urban Culture Research Composition Inspired by ASEAN Drums: Sakodai Rangsan Buathong+ & Bussakorn Binson++ (Thailand) Abstract This article describes the research behind a composition named Sakodai which is based on musical dialects found in Cambodia. Cambodia is one of the 10 countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). This Cambodian drum inspired composition is one of a set of 11 compositions titled ASEAN Drums where representative drums from each ASEAN country were selected (2 for each drum in Singapore). The drums included are the Sakodai of Cambodia, Sabadchai of Thai- land, Rebana Anak of Brunei, Pat Waing of Myanmar, Debakan of the Philippines, Rebana Ibu of Malaysia, Ping of Lao, Tay Son of Vietnam, Kendang of Indonesia and versions of Chinese drums and Indian Tablas from Singapore. Using these drums, 11 distinctive musical pieces were composed based on Thai traditional music theories and concepts. In this article, the composition inspired by rhythm patterns of the Cambodia Sakodai hand drum has been selected to be presented and discussed. The resulting piece is based on one Khmer dialect comprised of four lines with a medium tempo performed by a modified Thai Kantrum ensemble rooted in the dialect of traditional Khmer folk music from Cambodia. Keywords: ASEAN Drum, Thai Music Composition, Dialects in Music, Sakodai Drum, ASEAN Composition, Thai-Cambodian Composition + Rangsan Buathong, Grad Student, Faculty of Fine and Applied Arts, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand. voice: +66 814013061 email: [email protected]. ++ Bussakorn Binson, Board member, Center of Excellence for Thai Music and Culture Research,Chulalongkorn Uni- versity, Thailand. -

Singing the Lives of the Buddha: Lao Folk Opera As an Educational Medium

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 368 224 FL 800 756 AUTHOR Bernard-Johnston, Jean TITLE Singing the Lives of the Buddha: Lao Folk Opera as an Educational Medium. PUB DATE May 93 NOTE 351p.; Doctoral Dissertation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst. PUB TYPE Dissertations/Theses Doctoral Dissertations (041) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC15 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Acculturation; Buddhism; Culture Conflict; English (Second Language); Epistemology; *Folk Culture; *Land Settlement; *Lao; Native Language Instruction; *Opera; Refugees; *Teaching Methods; Uncommonly Taught Languages ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the role of Lao folk opera as a medium for constructively addressing problems of cultural conflict and acculturative stress that have risen among lowland Lao refugees and their children in urban America. The central focus of the inquiry is on the ways Lao folk opera currently functions as a learning medium in the resettlement context. The need for validation of such locally produced endogenous media has become increasingly apparent as long term resettlement issues continue to emerge as threats to linguistic and cultural diversity. The review of literature encompasses the role of oral specialists in traditional societies, Buddhist epistemology in the Theravada tradition, and community education in rural Lao culture. These sources provide the background necessary to an understanding of the medium's capacity for encapsulating culture and teaching ethical values in ways that connect past to present, distant to near. (Author) *********************************************************************** -

Cultural Landscape and Indigenous Knowledge of Natural Resource and Environment Management of Phutai Tribe

CULTURAL LANDSCAPE AND INDIGENOUS KNOWLEDGE OF NATURAL RESOURCE AND ENVIRONMENT MANAGEMENT OF PHUTAI TRIBE By Mr. Isara In-ya A Thesis Submitted in Partial of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Architectural Heritage Management and Tourism International Program Graduate School, Silpakorn University Academic Year 2014 Copyright of Graduate School, Silpakorn University CULTURAL LANDSCAPE AND INDIGENOUS KNOWLEDGE OF NATURAL RESOURCE AND ENVIRONMENT MANAGEMENT OF PHUTAI TRIBE By Mr. Isara In-ya A Thesis Submitted in Partial of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in Architectural Heritage Management and Tourism International Program Graduate School, Silpakorn University Academic Year 2014 Copyright of Graduate School, Silpakorn University The Graduate School, Silpakorn University has approved and accredited the Thesis title of “Cultural landscape and Indigenous Knowledge of Natural Resource and Environment Management of Phutai Tribe” submitted by Mr.Isara In-ya as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architectural Heritage Management and Tourism. …………………………………………………………... (Associate Professor Panjai Tantatsanawong, Ph.D.) Dean of Graduate School ……..……./………..…./…..………. The Thesis Advisor Professor Ken Taylor The Thesis Examination Committee …………………………………………Chairman (Associate Professor Chaiyasit Dankittikul, Ph.D.) …………../...................../................. …………………………………………Member (Emeritus Professor Ornsiri Panin) …………../...................../................ -

A History of Siamese Music Reconstructed from Western Documents 1505-1932

A HISTORY OF SIAMESE MUSIC RECONSTRUCTED FROM WESTERN DOCUMENTS 1505-1932 This content downloaded from 96.9.90.37 on Thu, 04 Feb 2021 07:36:11 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Introduction The writing of music history, the chief activity of the musicologist, depends almost entirely on the existence of written documents. Historical studies of various musics of the world have appeared wherever there are such documents: Europe, China, Japan, Korea, India, and in the Islamic cultural area of Western Asia and North Africa. Mainland Southeast Asia, however, has remained much of a musico-historical void since little has remained besides oral traditions and a few stone carvings, although Vietnamese music is an exception to this statement. The fact that these countries have so few trained musicologists also contributes to the lack of research. In the case of the Kingdom of Thailand, known before 1932 as Siam, little has been attempted in the way of music history in languages other than Thai, and those in Thai, also not plentiful, remain unknown to the outside world.l Only the European-trained Prince Damrong has attempted a comprehensive history, but it is based as much on tradition and conjecture as on concrete evidence and is besides quite brief. David Morton's classic study of Thai traditional music, The Traditional Music of Thailand, includes some eighteen pages of history, mostly based on oral traditions, conjecture, circumstantial evidence from neighboring musical cultures (Cambodia, China, and India), and some from the same documents used in this study. At least three reasons can be given for the lack of historical materials originating in Thailand. -

Volume 01, Issue 02 Annual International Conference on Recent

Volume 01, Issue 02 Volume 02, Issue 21 2nd International Conference on AnnualKnowledge Interna Economy,tional Conference Artificial on IntelligenceRecent Advances & Social in Sciences Business, Economics,KEAS - MaySocial-2019 Sciences and Humanities Tokyo Japan May 25-26, 2019 Tokyo Japan October 23-24, 2017 1 Full Paper Proceeding Book KEAS–Tokyo Japan 2nd International Conference on Knowledge Economy, Artificial Intelligence & Social Sciences May 25-26, 2019 Hotel Mystays Ochanomizu Conference Center 2 Copyright All rights reserved. No part of this publication maybe reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Applications for the copyright holder’s written permission to produce any part of this publication should be addressed to the publisher. Disclaimer Every reasonable effort has been made to ensure that the material in this book is true, correct, complete, and appropriate at the time of writing. Nevertheless, the publishers, the editors, and the authors do not accept responsibility for any omission or error, or for any injury, damage, lose, or financial consequences arising from the use of the book. The views expressed by the contributors do not necessarily reflect those of the TARIJ. ISBN: 978-969-670-827-8 Office Address: 7-8-1 Hongo, Bunkyo, Tokyo 113-0034 Email:[email protected] 3 Organizing Committee 1. Mr. Metin Gurani Conference Coordinator 2. Ishida Otaki Conference Coordinator 3. Hideo Owan Conference Coordinator 4 Conference Chair Message Dr Masayuki Otaki International Conference on “2nd International Conference on Knowledge Economy, Artificial Intelligence & Social Sciences” serves as platform that aims to help the scholarly community across nations to explore the critical role of multidisciplinary innovations for sustainability and growth of human societies. -

Song As Precedence to Dance: Understanding the Pedagogy Of

The Japan Foundation Asia Center Asia Fellowship Report Maria Christine Muyco Song as Precedence to Dance: Understanding The Pedagogy of Learning Kinnari in Ventiane, Laos By Maria Christine Muyco and Nouth Phouthavongsa (This research is funded by the Japan Foundation Asia Center) INTRODUCTION Noi or Nok is the Lao term for bird. In the Children Cultural Center of Sailom Village in Vientiane, Laos, you can hear children singing the repeated word “noi, noi, noi…”. The introduction of a song about “A lady who is a bird,” (referring to Kinnari), is one of the first things that is known in the Center. This is precedence to the actual dance of kinnari. Kinnari, side by side its lover, the kinnara, are protector gods in Buddhist and Hindu mythology. They are said to look after human beings from their home, the Himalayas. As celestial musicians, they are represented in musical instruments such as the Indian veena (lute) made after Kinnari, known as Kinnari Veena. In Southeast Asia, particularly, she is portrayed having a human head, torso, and arms; and a swan’s tail, wings, and feet. Inhabiting the Himavanta forest, she sings magical melodies with heartfelt poetry and dances gracefully. With her deep love and loyalty for her mate, she is admired and looked up to as a feminine symbol. This article focuses on what kinnari’ism means in Laos. In particular, it looks at the pedagogy used in the Center (which I refer to in short for Ventiane’s Children Cultural Center), the foundation venue for learning of the youth. The Center was established in 1994 with the initiative of the Ministry of Information, Culture, and Tourism whose objective is to promote national culture through children. -

Hmong Music in Northern Vietnam: Identity, Tradition and Modernity Qualification: Phd

Access to Electronic Thesis Author: Lonán Ó Briain Thesis title: Hmong Music in Northern Vietnam: Identity, Tradition and Modernity Qualification: PhD This electronic thesis is protected by the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. No reproduction is permitted without consent of the author. It is also protected by the Creative Commons Licence allowing Attributions-Non-commercial-No derivatives. If this electronic thesis has been edited by the author it will be indicated as such on the title page and in the text. Hmong Music in Northern Vietnam: Identity, Tradition and Modernity Lonán Ó Briain May 2012 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music University of Sheffield © 2012 Lonán Ó Briain All Rights Reserved Abstract Hmong Music in Northern Vietnam: Identity, Tradition and Modernity Lonán Ó Briain While previous studies of Hmong music in Vietnam have focused solely on traditional music, this thesis aims to counteract those limited representations through an examination of multiple forms of music used by the Vietnamese-Hmong. My research shows that in contemporary Vietnam, the lives and musical activities of the Hmong are constantly changing, and their musical traditions are thoroughly integrated with and impacted by modernity. Presentational performances and high fidelity recordings are becoming more prominent in this cultural sphere, increasing numbers are turning to predominantly foreign- produced Hmong popular music, and elements of Hmong traditional music have been appropriated and reinvented as part of Vietnam’s national musical heritage and tourism industry. Depending on the context, these musics can be used to either support the political ideologies of the Party or enable individuals to resist them. -

Thai Musical Instruments: Development of Innovative Multimedia to Enhance Learning Among Secondary Level Education Students (M.1 to M.3) in Bangkok

Asian Social Science; Vol. 9, No. 13; 2013 ISSN 1911-2017 E-ISSN 1911-2025 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Thai Musical Instruments: Development of Innovative Multimedia to Enhance Learning among Secondary Level Education Students (M.1 to M.3) in Bangkok Prapassorn Tanta-o-Pas1, Songkoon Chantachon1 & Marisa Koseyayothin2 1 The Faculty of Cultural Science, Mahasarakham University, Khamriang Sub-District, Kantarawichai District, Maha Sarakham, Thailand 2 Kanchanapisek Non-Formal Education Centre (Royal Academy), Salaya Sub-District, Bhuttamonthon District, Nakhon Pathom, Thailand Correspondence: Prapassorn Tanta-o-Pas, The Faculty of Cultural Science, Mahasarakham University, Khamriang Sub-District, Kantarawichai District, Maha Sarakham 44150, Thailand. E-mail: [email protected] Received: June 4, 2013 Accepted: July 26, 2013 Online Published: September 29, 2013 doi:10.5539/ass.v9n13p163 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ass.v9n13p163 Abstract Thai music is a part of Thai cultural heritage that has been accumulated and inherited over time. Value should be placed on the knowledge and conservation of Thai music so that it may exist in modern Thai society. This research is a cultural research with three aims: a) to study the historical background of Thai music; b) to study the problems, requirements and methods of learning for Thai music; c) to develop innovative multimedia to enhance learning of Thai music. The results of the research found that Thai music is derived from local Thai wisdom and is a part of cultural heritage that has unique characteristics and formats to clearly indicate its Thai identity. The success of Thai music teaching is dependent on the interest of the students and different forms of multimedia are tools that can create stimulation and enhance learning of the subject. -

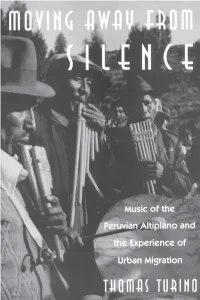

Moving Away from Silence: Music of the Peruvian Altiplano and the Experiment of Urban Migration / Thomas Turino

MOVING AWAY FROM SILENCE CHICAGO STUDIES IN ETHNOMUSICOLOGY edited by Philip V. Bohlman and Bruno Nettl EDITORIAL BOARD Margaret J. Kartomi Hiromi Lorraine Sakata Anthony Seeger Kay Kaufman Shelemay Bonnie c. Wade Thomas Turino MOVING AWAY FROM SILENCE Music of the Peruvian Altiplano and the Experience of Urban Migration THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS Chicago & London THOMAS TURlNo is associate professor of music at the University of Ulinois, Urbana. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 1993 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 1993 Printed in the United States ofAmerica 02 01 00 99 98 97 96 95 94 93 1 2 3 4 5 6 ISBN (cloth): 0-226-81699-0 ISBN (paper): 0-226-81700-8 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Turino, Thomas. Moving away from silence: music of the Peruvian Altiplano and the experiment of urban migration / Thomas Turino. p. cm. - (Chicago studies in ethnomusicology) Discography: p. Includes bibliographical references and index. I. Folk music-Peru-Conirna (District)-History and criticism. 2. Folk music-Peru-Lirna-History and criticism. 3. Rural-urban migration-Peru. I. Title. II. Series. ML3575.P4T87 1993 761.62'688508536 dc20 92-26935 CIP MN @) The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI 239.48-1984. For Elisabeth CONTENTS List of Illustrations ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction: From Conima to Lima -

339 Chapter Six Three Royal Wats Through the Turmoil

CHAPTER SIX THREE ROYAL WATS THROUGH THE TURMOIL OF NATIONALIST GOVERNMENTS AND DICTATOR REGIMES (1910-1957) Introduction In the previous chapter, we saw how the royal wats lost their sources of direct state support, resulting in their dependence on rent revenues derived from their donated land and their abbots became responsible for their physical condition. Real estate properties of wats became the key for their survival, and the royal government also supported them to be independent entities in the market economy. In this chapter, we will see the increasing gap between the government and the Buddhist monastic order. This was especially the case after King Vajiravudh appointed his uncle and preceptor, Prince Wachirayan as the Supreme Patriarch, whose control of monastic affairs included urging wats to manage and invest in their land properties. Moreover, he also developed strategies to increase the Buddhist religious central assets, with the aim of making the Buddhist monastic order more independent from the state. He also created primary schools and Buddhist standard texts and promoted monastic practices which supported the unity of the nation in keeping with King Vajiravudh’s ultra-nationalist ideology. In this reign, the wats and monks were separated from the management of public education. Moreover, the king did not support any new construction or preservation of the royal wats as previous rulers had in the past. Therefore, royal wats lost their prominent role in society and state affairs, but at the same time they gained significant financial stability in terms of their private investment. After the bloodless revolution in 1932, King Prachathipok (Rama VII) became a constitutional monarch and the People’s Party comprised of lower ranking officials took control of the kingdom. -

10Th Anniversary, College of Music, Mahasarakham University, Thailand

Mahasarakham University International Seminar on Music and the Performing Arts 1 Message from the Dean of College of Music, Mahasarakham University College of Music was originally a division of the Faculty of Fine and Applied Arts that offers a Bachelor of Arts program in Musical Art under the the operation of Western Music, Thai Classical music and Folk Music. The college officially established on September 28, 2007 under the name “College of Music” offering an undergraduate program in musical art as well as master’s and doctoral degree programs. At this 10th anniversary, the College is a host for events such as the international conference and also music and dance workshop from countries who participate and join us. I wish this anniversary cerebration will be useful for scholars from many countries and also students from the colleges and universities in Thailand. I thank everyone who are in charge of this event. Thank you everyone for joining us to cerebrate, support and also enhance our academic knowledge to be shown and shared to everyone. Thank you very much. Best regards, (Khomkrich Karin, Ph.D.) Dean, College of Music Mahasarakham University 10th Anniversary, College of Music, Mahasarakham University, Thailand. 2 November 28 – December 1, 2018 Message from the Director of Kalasin College of Dramatic Arts For the importance of the Tenth Anniversary of the College of Music, Masarakham University. the Kalasin College of Dramatic Arts, Bunditpatanasilpa Institute, feels highly honored to co-host this event This international conference-festival would allow teachers, students and researchers to present and publicize their academic papers in music and dance.