The Effects of Globalization on the Status of Music in Thai Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gmm Grammy Public Company Limited | Annual Report 2013

CONTENTS 20 22 24 34 46 Message from Securities and Management Board of Directors Financial Highlights Chairman and Shareholder Structure and Management Group Chief Information team Executive Officer 48 48 48 50 52 Policy and Business Vision, Mission and Major Changes and Shareholding Revenue Structure Overview Long Term Goal Developments Structure of the and Business Company Group Description 82 85 87 89 154 Risk Factors Management Report on the Board Report of Sub-committee Discussion and of Directors' Independent Report Analysis Responsibility Auditor and towards the Financial Financial Statement Statements 154 156 157 158 159 Audit Committee Risk Management Report of the Report of the Corporate Report Committee Report Nomination and Corporate Governance Remuneration Governance and Committee Ethics Committee 188 189 200 212 214 Internal Control and Connected Corporate Social Details of the General Information Risk Management Transactions Responsibilities Head of Internal and Other Audit and Head Significant of Compliance Information 214 215 220 General Information Companies in which Other Reference Grammy holds more Persons than 10% Please see more of the Company's information from the Annual Registration Statement (Form 56-1) as presented in the www.sec.or.th. or the Company's website 20 ANNUAL REPORT 2013 GMM GRAMMY Mr. Paiboon Damrongchaitham Ms. Boosba Daorueng Chairman of the Board of Directors Group Chief Executive Officer …As one of the leading and largest local content providers, with long-standing experiences, GMM Grammy is confident that our DTT channels will be channels of creativity and quality, and successful. They will be among favorite channels in the mind of viewers nationwide, and can reach viewers in all TV platforms. -

Psaudio Copper

Issue 116 JULY 27TH, 2020 “Baby, there’s only two more days till tomorrow.” That’s from the Gary Wilson song, “I Wanna Take You On A Sea Cruise.” Gary, an outsider music legend, expresses what many of us are feeling these days. How many conversations have you had lately with people who ask, “what day is it?” How many times have you had to check, regardless of how busy or bored you are? Right now, I can’t tell you what the date is without looking at my Doug the Pug calendar. (I am quite aware of that big “Copper 116” note scrawled in the July 27 box though.) My sense of time has shifted and I know I’m not alone. It’s part of the new reality and an aspect maybe few of us would have foreseen. Well, as my friend Ed likes to say, “things change with time.” Except for the fact that every moment is precious. In this issue: Larry Schenbeck finds comfort and adventure in his music collection. John Seetoo concludes his interview with John Grado of Grado Labs. WL Woodward tells us about Memphis guitar legend Travis Wammack. Tom Gibbs finds solid hits from Sophia Portanet, Margo Price, Gerald Clayton and Gillian Welch. Anne E. Johnson listens to a difficult instrument to play: the natural horn, and digs Wanda Jackson, the Queen of Rockabilly. Ken hits the road with progressive rock masters Nektar. Audio shows are on hold? Rudy Radelic prepares you for when they’ll come back. Roy Hall tells of four weddings and a funeral. -

Annual Report 2010

GMM GRAMMY PUBLIC COMPANY LIMITED ANNUAL REPORT 2010 CONTENTS Messsage From Chairman And Co-Chief Excutive Officers 004 Audit Committee Report 005 Board Of Directors 006 Executive Committee And Organization Chart 012 Business Structure & Investment Structure 013 Corporate Social Responsibility 016 Financial Highlights 030 Revenue Structure 031 General Information 032 Risk Factors 052 Captial, Management Structure And Corporate Governance 054 Connected Transactions 086 Corporate Governance Report 095 Management Discussion And Analysis 096 Report On The Board Of Director’s Responsibility 097 Towards The Financial Statements Independent Auditor’s Report And Financial Statements 098 Companies In Which Gmm Grammy Holds More Than 10% 147 Details of Board of Directors And Management Team 150 Other Reference Persons 159 MESSSAGE FROM CHAIRMAN AND CO-CHIEF EXCUTIVE OFFICERS MESSSAGE FROM CHAIRMAN AND CO-CHIEF EXCUTIVE OFFICERS Dear Shareholders, In 2010, the Company adjusted and developed its music The publishing business line has increasingly shifted over to business so that revenue streams primarily came from three new media. For instance, Maxim is published in an e-gazine. business lines: digital music, artist management, and show Content from this business line will also be increasingly business. This was accomplished by reducing the production applied to satellite business, as well as selling content capacity of physical products, and ramping up sales of digital through new electronic gadgets such as the iPad. music to better match the lifestyles of consumer behavior that The movie business line produced a total of three films, has shifted in tandem with modern technological innovations. of which “Kuen Muen Ho” (‘Hello Stranger’) brought in Baht The Company believes that making these changes will 126.3 million, making it the highest box office revenue making support and strengthen Grammy’s content so that it can be Thai film screened in 2010. -

The 1960S Thai Pop Music and Bangkok Youth Culture

Rebel without Causes: The 1960s Thai Pop Music and Bangkok Youth Culture Viriya Sawangchot Mahidol University E-mail: [email protected] Abstract In this paper, I would like to acknowledge that 1960s to the 1970s American popular culture, particularly in rock ‘n’ roll music, have Been contested By Thai context. In term oF this, the paper intends to consider American rock ’n’ roll has come to Function as a mode oF humanization and emancipation oF Bangkok youngster rather than ideological domination. In order to understand this process, this paper aims to Focus on the origins and evolution oF rock ‘n’ roll and youth culture in Bangkok in the 1960s to 1970s. The Birth of pleng shadow and pleng string will be discussed in this context as well. Keywords: Thai Pop Music, Bangkok Youth Culture, ideological domination 1 Rebel without Causes: The 1960s Thai Pop Music and Bangkok Youth Culture Viriya Sawangchot Introduction In Thailand, the Cold War and Modernization era began with the Coup of 1958 which led by Field-Marshall Sarit Tanarat. ConseQuently, the modernizing state run By military junta, the Sarit regime (1958-1964) and his coup colleague, Field –Marshall Thanom Kittikajon (1964 -1973), has done many things such as education, development and communication, with strongly supported By U.S. Cold War policy and Thai elite incorporating the new landscape politico-cultural power with regardless to the issues oF democracy, human rights, and social justice(Chaloemtiarana 1983). The American Cold war’s polices also contriButed to increasing capital Flow in Thailand, which also meant increasing the gloBal cultural Flow and the educational rate( Phongpaichai and Baker1997). -

Deborah's M.A Thesis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarBank@NUS Created in its own sound: Hearing Identity in The Thai Cinematic Soundtrack Deborah Lee National University of Singapore 2009 Acknowledgements Heartfelt thanks goes out to the many people that have helped to bring this thesis into fruition. Among them include the many film-composers, musicians, friends, teachers and my supervisors (both formal and informal) who have contributed so generously with their time and insights. Professor Rey, Professor Goh, Prof Irving, Prof Jan, Aajaarn Titima, Aajaarn Koong, Aajaarn Pattana, I really appreciate the time you took and the numerous, countless ways in which you have encouraged me and helped me in the process of writing this thesis. Pitra and Aur, thank you for being such great classmates. The articles you recommended and insights you shared have been invaluable to me in the research and writing of my thesis. Rohani, thanks for facilitating all the administrative details making my life as a student so much easier. Chatchai, I’ve been encouraged and inspired by you. Thank you for sharing so generously of your time and love for music. Oradol, thank you so much for the times we have had together talking about Thai movies and music. I’ve truly enjoyed our conversations. There are so many other people that have contributed in one way or the other to the successful completion of this thesis. The list goes on and on, but unfortunately I am running out of time and words…. Finally, I would like to thank God and acknowledge His grace that has seen me through in the two years of my Masters program in the Department of Southeast Asian Studies. -

The Lao in Sydney

Sydney Journal 2(2) June 2010 ISSN 1835-0151 http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/ojs/index.php/sydney_journal/index The Lao in Sydney Ashley Carruthers Phouvanh Meuansanith The Lao community of Sydney is small and close-knit, and concentrated in the outer southwest of the city. Lao refugees started to come to Australia following the takeover by the communist Pathet Lao in 1975, an event that caused some 10 per cent of the population to flee the country. The majority of the refugees fled across the Mekong River into Thailand, where they suffered difficult conditions in refugee camps, sometimes for years, before being resettled in Australia. Lao Australians have managed to rebuild a strong sense of community in western Sydney, and have succeeded in establishing two major Theravada Buddhist temples that are foci of community life. Lao settlement in south-western Sydney There are some 5,551 people of Lao ancestry resident in Sydney according to the 2006 census, just over half of the Lao in Australia (10,769 by the 2006 census). The largest community is in the Fairfield local government area (1,984), followed by Liverpool (1,486) and Campbelltown (1,053). Like the Vietnamese, Lao refugees were initially settled in migrant hostels in the Fairfield area, and many stayed and bought houses in this part of Sydney. Fairfield and its surrounding suburbs offered affordable housing and proximity to western Sydney's manufacturing sector, where many Lao arrivals found their first jobs and worked until retirement. Cabramatta and Fairfield also offer Lao people resources such as Lao grocery stores and restaurants, and the temple in Edensor Park is nearby. -

Dutch Pop Music Is Here to Stay

DUTCH POP MUSIC IS HERE TO STAY Continuïteit en vernieuwing van het aanbod van Nederlandse popmuziek 1960-1990 Olivier van der Vet Uitgever: ERMeCC, Erasmus Research Centre for Media, Communication and Culture Drukker: Ridderprint Ridderkerk Omslagontwerp: Nikki Vermeulen Ridderprint ISBN: 978-90-76665-24-5 © Olivier van der Vet, 2013 DUTCH POP MUSIC IS HERE TO STAY: Continuïteit en vernieuwing van het aanbod van Nederlandse popmuziek 1960-1990 Dutch Pop Music Is Here To Stay: Continuity and Innovation of Dutch Pop Music between 1960-1990 Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam op gezag van de rector magnificus Prof.dr. H.G. Schmidt en volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties. De openbare verdediging zal plaatsvinden op donderdag, 16 mei 2013 om 15.30 uur door Olivier Nicolo Sebastiaan van der Vet geboren te ‘s-Gravenhage Promotiecommissie: Promotor: Prof. dr. A.M. Bevers Overige leden: Prof. dr. C.J.M van Eijck Prof. dr. G. De Meyer Prof. dr. P.W.M. Rutten Copromotor: Dr. W. de Nooy VOORWOORD Continuïteit en vernieuwing zijn de twee termen die in dit onderzoek centraal staan. Nederlandse artiesten zijn op zoek naar continuïteit in hun loopbaan en platenmaatschappijen naar continuïteit in de productie. In dit streven vinden zij elkaar en ontstaat het aanbod. Continuïteit stond ook centraal in het traject dat ik heb afgelegd voor dit promotieonderzoek. Vanaf de start, toen ik als onderzoeker bij het Erasmus Centrum voor Kunst- en Cultuurwetenschappen (ECKCW) werkte, tot nu, is het promotieonderzoek een constante factor geweest. Wat er in deze periode ook is veranderd, het promotieonderzoek bleef. -

2588Booklet.Pdf

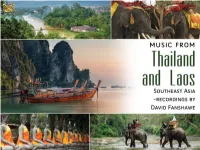

ENGLISH P. 2 DEUTSCH S. 8 MUSIC FROM THAILAND AND LAOS SOUTHEAST ASIA – RECORDINGS BY DAVID FANSHAWE DAVID FANSHAWE David Fanshawe was a composer, ethnic sound recordist, guest speaker, photographer, TV personality, and a Churchill Fellow. He was born in 1942 in Devon, England and was educated at St. George’s Choir School and Stowe, after which he joined a documentary film company. In 1965 he won a Foundation Scholarship to the Royal College of Music in London. His ambition to record indigenous folk music began in the Middle East in 1966, and was intensified on subsequent journeys through North and East Africa (1969 – 75) resulting in his unique and highly original blend of Music and Travel. His work has been the subject of BBC TV documentaries including: African Sanctus, Arabian Fantasy, Musical Mariner (National Geographic) and Tropical Beat. Compositions include his acclaimed choral work African Sanctus; also Dona nobis pacem – A Hymn for World Peace, Sea Images, Dover Castle, The Awakening, Serenata, Fanfare to Planet Earth / Millennium March. He has also scored many film and TV productions including Rank’s Tarka the Otter, BBC’s When the Boat Comes In and ITV’s Flambards. Since 1978, his ten years of research in the Pacific have resulted in a monumental archive, documenting the music and oral traditions of Polynesia, Micronesia and Melanesia. David has three children, Alexander and Rebecca with his first wife Judith; and Rachel with his second wife Jane. David was awarded an Honorary Degree of Doctor of Music from the University of the West of England (UWE) in 2009. -

The Khaen: Place, Power, Permission, and Performance

THE KHAEN: PLACE, POWER, PERMISSION, AND PERFORMANCE by Anne Greenwood B.Mus., The University of British Columbia, 2011 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in The Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies (Ethnomusicology) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA Vancouver June 2016 © Anne Greenwood, 2016 Abstract While living in the Isan region of Thailand I had the opportunity to start learning the traditional wind instrument the khaen (in Thai, แคน, also transliterated as khène). This thesis outlines the combination of methods that has allowed me to continue to play while tackling broader questions surrounding permission and place that arise when musicians, dancers, or artists work with materials from other cultures. Through an examination of the geographical, historical, and social contexts of the Isan region I have organized my research around the central themes of place, power, permission, and performance. My intent is to validate the process of knowledge acquisition and the value of what one has learned through action, specifically musical performance, and to properly situate such action within contemporary practice where it can contribute to the development and continuation of an endangered art form. ii Preface This thesis is original, unpublished, independent work by the author, Anne Greenwood. iii Table of Contents Abstract .......................................................................................................................................... ii Preface -

Suggested Serving: 1. WOODEN STARS 2. COLDCUT 3. HANIN ELIAS 4. WINDY & CARL 5. SOUTHERN CULTURE on the SKIDS 6. CORNERSHOP

December, 1997 That Etiquette Magazine from CiTR 101.9 fM FREE! 1. Soupspoon 2. Dinner knife 3. Plate 4. Dessert fork 5. Salad fork 6. Dinner fork 7. Napkin 8. Bread and butter plate 9. Butter spreader 10. Tumbler u Suggested Serving: 1. WOODEN STARS 2. COLDCUT 3. HANIN ELIAS 4. WINDY & CARL 5. SOUTHERN CULTURE on the SKIDS 6. CORNERSHOP 7. CiTR ON-AIR PROGRAMMING GUIDE Dimm 1997 I//W 179 f€fltUf€J HANIN ELIAS 9 WOODEN STARS 11 WINDY & CARL 12 CORNERSHOP 14 SOUTHERN CULTURE ON THE SKIDS 16 COLDCUT 19 GARAGESHOCK 20 COUUAM COWSHEAD CHRONICLES VANCOUVER SPECIAL 4 INTERVIEW HELL 6 SUBCULT. 8 THE KINETOSCOPE 21 BASSLINES 22 SEVEN INCH 22 PRINTED MATTERS 23 UNDER REVIEW 24 REAL LIVE ACTION 26 ON THE DIAL 28 e d i t r i x : miko hoffman CHARTS 30 art director: kenny DECEMBER DATEBOOK 31 paul ad rep: kevin pendergraft production manager: tristan winch Comic* graphic design/ Layout: kenny, atomos, BOTCHED AMPALLANG 4 michael gaudet, tanya GOOD TASTY COMIC 25 Schneider production: Julie colero, kelly donahue, bryce dunn, andrea gin, ann Coucr goncalves, patrick gross, jenny herndier, erin hoage, christa 'Tis THE SEASON FOR EATIN', LEAVING min, katrina mcgee, sara minogue, erin nicholson, stefan YER ELBOWS OFF THE TABLE AND udell, malcolm van deist, shane MINDING YER MANNERS! PROPER van der meer photogra- ETIQUETTE COVER BY ARTIST phy/i L Lustrations: jason da silva, ted dave, TANYA SCHNEIDER. richard folgar, sydney hermant, mary hosick, kris rothstein, corin sworn contribu © "DiSCORDER* 1997 by the Student Radio Society of the University of British Columbia. -

Development of Lifestyle Following Occupational Success As a Mor Lam Artist

Asian Culture and History; Vol. 7, No. 1; 2015 ISSN 1916-9655 E-ISSN 1916-9663 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Development of Lifestyle Following Occupational Success as a Mor Lam Artist Supap Tinnarat1, Sitthisak Champadaeng1 & Urarom Chantamala1 1 The Faculty of Cultural Science, Mahasarakham University, Khamriang Sub-District, Kantarawichai District, Maha Sarakham Province, Thailand Correspondence: Supap Tinnarat, The Faculty of Cultural Science, Mahasarakham University, Khamriang Sub-District, Kantarawichai District, Maha Sarakham Province 44150, Thailand. E-mail: [email protected] Received: July 9, 2013 Accepted: July 15, 2014 Online Published: September 22, 2014 doi:10.5539/ach.v7n1p91 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ach.v7n1p91 Abstract Mor Lam is a folk performing art that originates from traditions in the locality and customs of religion. There are some current problems with Mor Lam, especially in the face of globalization. Mor Lam suffers as traditional beliefs and values decrease. Society is rapidly changing and the role of the mass media has increased. Newer media provide knowledge and entertainment in ways that make it impossible for Mor Lam to compete. This research used a cultural qualitative research method and had three main aims: to study the history of Mor Lam artists, to study the present conditions and lifestyle of successful Mor Lam performers and to develop the lifestyle of successful Mor Lam performers. The research was carried out from July 2011 to October 2012. Data was collected through field notes, structured and non-structured interviews, participant and non-participant observation and focus group discussion. The results show that Mor Lam is a performance style that has been very popular in the Isan region. -

Lukthung Classification Using Neural Networks on Lyrics and Audios

Lukthung Classification Using Neural Networks on Lyrics and Audios Kawisorn Kamtue∗, Kasina Euchukanonchaiy, Dittaya Wanvariez and Naruemon Pratanwanichx ∗yTencent (Thailand) zxDepartment of Mathematics and Computer Science, Faculty of Science, Chulalongkorn University, Thailand Email: ∗[email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Many musical genre classification methods rely heavily on Abstract—Music genre classification is a widely researched audio files, either raw waveforms or frequency spectrograms, topic in music information retrieval (MIR). Being able to as predictors. Previously, traditional approaches focused on automatically tag genres will benefit music streaming service providers such as JOOX, Apple Music, and Spotify for their hand-crafted feature extraction to be input to classifiers [3], content-based recommendation. However, most studies on music [4], while more recent network-based approaches view spec- classification have been done on western songs which differ from trograms as 2-dimensional images for musical genre classifi- Thai songs. Lukthung, a distinctive and long-established type of cation [5]. Thai music, is one of the most popular music genres in Thailand Lyrics-based music classification is less studied, as it has and has a specific group of listeners. In this paper, we develop neural networks to classify such Lukthung genre from others generally been less successful [6]. Early approaches designed using both lyrics and audios. Words used in Lukthung songs lyrics features that were comprised of vocabulary, styles, are particularly poetical, and their musical styles are uniquely semantics, orientations and, structures for SVM classifiers [7]. composed of traditional Thai instruments. We leverage these two Since modern natural language processing techniques have main characteristics by building a lyrics model based on bag-of- switched to recurrent neural networks (RNNs), lyrics-based words (BoW), and an audio model using a convolutional neural network (CNN) architecture.