Version Définitive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modern Yokai How Japan Embraced Their Monsters

Modern Yokai How Japan embraced their monsters. What are Yokai? The kanji used for Yokai doesn’t have a simple/exact English translation. Yokai are a class of supernatural entities and spirits in Japanese folklore. They range from dangerous and aggressive to helpful and fortuitous. Some are as strong as gods, others are spirits of nature, and others are just lil’guys…who want to give you tofu on a dark road at night. Forewarning: I am NOT a yokai expert. I have tried to stay as close to the official historical information on these guys as possible, but some less accurate things may pop up. Please don’t come at me. I’m very weak and insecure. ALSO there are some adult themes throughout. Kitsune (lit. fox/ fox spirit) Two major variations. *Zenko Holy foxes are servants of the Shinto deity Inari, shrines decorated with statues and images of foxes. These holy foxes act as messengers of the gods and mediums between the celestial and human worlds, protect humans or places, provide good luck, and ward evil spirits away. We are not talking about those ones. More common are the *Yako wild foxes which delight in mischief, pranks, or evil, wild foxes trick or even possess humans, and make them behave strangely. Kitsune are often associated with fire, “kitsunebi” or Fox-fire, similar in a way to “wil-o-wisps”, created by kitsune breathing fire into lanternlight orbs to light paths for other yokai or to trick humans. Kitsune are extremely intelligent and powerful shape-shifters. They frequently harass humans by transforming into fearsome monsters *giants, trains, oni etc. -

Spirits, Monsters, Ghosts, Oh My!: Texts to Understand the Supernatural Japan

Spirits, Monsters, Ghosts, Oh My!: Texts to Understand the Supernatural Japan Possible Partnerships: Department of East Asian Languages & Literature, University of Pittsburgh Department of Religious Studies, The Japan-America Society of Pennsylvania Grades: 7-12 Resources: Resources are cited below in MLA format Proposal: This proposal/lesson part of the NCTA Integrative Initiative works a little differently than all the other ones. All of the other proposals dealt with rather concrete aspects of culture or learning that can be quantified or experienced in real-time. Whether it be reading literature, learning about kendo, or taking part in learning and making art as an educator, most of the ideas that have heretofore been mentioned are mostly tactile to an extent. Not so with this proposal. The subject matter presented here deals far more with understanding, explaining, and comprehending the importance of certain cultural ideas. Japan’s sense of the religious, spiritual, and supernatural can be different from the way Westerners understand these concepts. As such, the Japanese views, history, and traditions related to these concepts are not as well known as other aspects of Japanese history and culture such as samurai, noh and kabuki, and anime. In this regard, an educator who is teaching or discussing Japan with their students should do their best to give their students the resources and experiences necessary to fully integrate these ideas into the overall picture of Japan they may develop during their time in the classroom. As such, the teacher can use textual resources to supplement any textbook material they may be using in their classrooms, or for the sake of teaching a unique lesson altogether. -

The Selected Poems of Yosa Buson, a Translation Allan Persinger University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2013 Foxfire: the Selected Poems of Yosa Buson, a Translation Allan Persinger University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Asian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Persinger, Allan, "Foxfire: the Selected Poems of Yosa Buson, a Translation" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 748. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/748 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FOXFIRE: THE SELECTED POEMS OF YOSA BUSON A TRANSLATION By Allan Persinger A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee May 2013 ABSTRACT FOXFIRE: THE SELECTED POEMS OF YOSA BUSON A TRANSLATION By Allan Persinger The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2013 Under the Supervision of Professor Kimberly M. Blaeser My dissertation is a creative translation from Japanese into English of the poetry of Yosa Buson, an 18th century (1716 – 1783) poet. Buson is considered to be one of the most important of the Edo Era poets and is still influential in modern Japanese literature. By taking account of Japanese culture, identity and aesthetics the dissertation project bridges the gap between American and Japanese poetics, while at the same time revealing the complexity of thought in Buson's poetry and bringing the target audience closer to the text of a powerful and mov- ing writer. -

Fine Japanese and Korean Art New York I September 12, 2018 Fine Japanese and Korean Art Wednesday 12 September 2018, at 1Pm New York

Fine Japanese and Korean Art New York I September 12, 2018 Fine Japanese and Korean Art Wednesday 12 September 2018, at 1pm New York BONHAMS BIDS INQUIRIES CLIENT SERVICES 580 Madison Avenue +1 (212) 644 9001 Japanese Art Department Monday – Friday 9am-5pm New York, New York 10022 +1 (212) 644 9009 fax Jeffrey Olson, Director +1 (212) 644 9001 www.bonhams.com [email protected] +1 (212) 461 6516 +1 (212) 644 9009 fax [email protected] PREVIEW To bid via the internet please visit ILLUSTRATIONS Thursday September 6 www.bonhams.com/24862 Takako O’Grady, Front cover: Lot 1082 10am to 5pm Administrator Back cover: Lot 1005 Friday September 7 Please note that bids should be +1 (212) 461 6523 summited no later than 24hrs [email protected] 10am to 5pm REGISTRATION prior to the sale. New bidders Saturday September 8 IMPORTANT NOTICE 10am to 5pm must also provide proof of identity when submitting bids. Please note that all customers, Sunday September 9 irrespective of any previous activity 10am to 5pm Failure to do this may result in your bid not being processed. with Bonhams, are required to Monday September 10 complete the Bidder Registration 10am to 5pm Form in advance of the sale. The form LIVE ONLINE BIDDING IS Tuesday September 11 can be found at the back of every AVAILABLE FOR THIS SALE 10am to 3pm catalogue and on our website at Please email bids.us@bonhams. www.bonhams.com and should SALE NUMBER: 24862 com with “Live bidding” in the be returned by email or post to the subject line 48hrs before the specialist department or to the bids auction to register for this service. -

A Tanizaki Feast

A Tanizaki Feast Michigan Monograph Series in Japanese Studies Number 24 Center for Japanese Studies, The University of Michigan A Tanizaki Feast The International Symposium in Venice Edited by Adriana Boscaro and Anthony Hood Chambers Center for Japanese Studies The University of Michigan Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1998 Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/ Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. 1998 The Regents of the University of Michigan Published by the Center for Japanese Studies, The University of Michigan, 202 S. Thayer St., Ann Arbor, MI 48104-1608 Distributed by The University of Michigan Press, 839 Greene St. / P.O. Box 1104, Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1104 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data A Tanizaki feast: the international symposium in venice / edited by Adriana Boscaro and Anthony Hood Chambers. xi, 191 p. 23.5 cm. — (Michigan monograph series in Japanese studies ; no. 24) Includes index. ISBN 0-939512-90-4 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Tanizaki, Jun'ichir5, 1886—1965—Criticism and interpreta- tion—Congress. I. Boscaro, Adriana. II. Chambers, Anthony H. (Anthony Hood). III. Series. PL839.A7Z7964 1998 895.6'344—dc21 98-39890 CIP Jacket design: Seiko Semones This publication meets the ANSI/NISO Standards for Permanence of Paper for Publications and Documents in Libraries and Archives (Z39.48-1992). Published in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-939512-90-4 (hardcover) ISBN 978-0-472-03838-1 (paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12816-7 (ebook) ISBN 978-0-472-90216-3 (open access) The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Contents Preface vii The Colors of Shadows 1 Maria Teresa Orsi The West as Other 15 Paul McCarthy Prefacing "Sorrows of a Heretic" 21 Ken K. -

Fine Japanese and Korean Art I New York I September 11, 2019

Fine Japanese and Korean Art and Korean Fine Japanese I New York I September 11, 2019 I New York Fine Japanese and Korean Art New York I September 11, 2019 Fine Japanese and Korean Art New York | Wednesday September 11, 2019, at 1pm BONHAMS BIDS INQUIRIES CLIENT SERVICES 580 Madison Avenue +1 (212) 644 9001 Japanese Art Department Monday – Friday 9am-5pm New York, New York 10022 +1 (212) 644 9009 fax Jeffrey Olson, Director +1 (212) 644 9001 bonhams.com [email protected] +1 (212) 461 6516 +1 (212) 644 9009 fax [email protected] PREVIEW To bid via the internet please visit REGISTRATION www.bonhams.com/25575 Thursday September 5 Takako O’Grady IMPORTANT NOTICE 10am to 5pm +1 (212) 461 6523 Please note that all customers, Friday September 6 Please note that bids should be [email protected] irrespective of any previous activity 10am to 5pm summited no later than 24hrs with Bonhams, are required to Saturday September 7 prior to the sale. New bidders complete the Bidder Registration 10am to 5pm must also provide proof of Form in advance of the sale. The Sunday September 8 identity when submitting bids. form can be found at the back 10am to 5pm Failure to do this may result in of every catalogue and on our Monday September 9 your bid not being processed. website at www.bonhams.com 10am to 5pm and should be returned by email or Tuesday September 10 LIVE ONLINE BIDDING IS post to the specialist department 10am to 3pm AVAILABLE FOR THIS SALE or to the bids department at Please email bids.us@bonhams. -

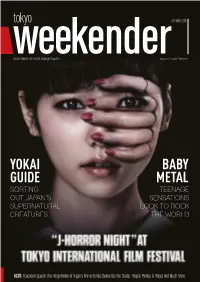

Yokai Guide Baby Metal

OCTOBER 2015 Japan’s number one English language magazine Image © 2015 “Gekijorei” Film Partners YOKAI BABY GUIDE METAL SORTING TEENAGE OUT JAPAN’S SENSATIONS SUPERNATURAL LOOK TO ROCK CREATURES THE WORLD ALSO: Education Special, the Hoop Nation of Nippon, Marie Kondo Cleans Out the Clutter, People, Parties, & Placeswww.tokyoweekender.com and Much MoreOCTOBER 2015 OCTOBER 2015 www.tokyoweekender.com OCTOBER 2015 CONTENTS 15 MASTERS OF J-HORROR The Tokyo International Film Festival brings plenty of screams to the screen © 2015 “Gekijorei” Film Partners 14 16 20 BABYMETAL YOKAI GUIDE EDUCATION SPECIAL Awww...These teenagers are on a rock- Don’t know your kappa from your kirin? Autumn is filled with new developments fueled musical rampage Turn to page 16, dear friends at Tokyo’s international schools 6 The Guide 13 Akita-Style Teppanyaki 34 Previews Our recommendations for hot fall looks, Get ready for some of Japan’s finest The back story of Peter Pan, Keanu takes plus a snack that’s worth a train ride ingredients, artfully prepared at Gomei revenge, and the Not-So-Fantastic Four 8 Gallery Guide 28 Marie Kondo 36 Agenda Edo period adult art, the College Women’s Reclaiming joy by getting rid of clutter? Shimokita Curry Festival, Tokyo Design Association of Japan Print Show, and more Sounds like a win-win Week, and other October happenings 10 Japan Hoops It Up 30 People, Parties, Places 38 Back in the Day Lace ‘em up and get fired up for the A very French soirée, a tasty evening for Looking back at a look ahead to the CWAJ coming season of NBA action Peru, and Bill back in the Studio 54 days Print Show, circa 1974 www.tokyoweekender.com OCTOBER 2015 THIS MONTH IN THE WEEKENDER and domestic for decades, and this year the Tokyo International Film Festival OCTOBER 2015 has decided to take a walk on the spooky side, celebrating the work of three masters of “J-Horror,” including Hideo Nakata, whose upcoming release “Ghost Theater” gets the cover this month. -

Seres Fantásticos Japoneses En La Literatura Y En El Cine: Obakemono

Belphégor Cora Requena Hidalgo Seres fantásticos japoneses en la literatura y en el cine: Obakemono, yūrei, yōkai y kaidan A estas alturas del siglo XXI hablar de rasgos característicos en la cultura japonesa puede resultar repetitivo y cansino. En su deseo de aproximarse al mundo japonés, que invade hoy Occidente con sorprendentes formas de discurso que inyectan nueva energía a las ya cansadas y tradicionales formas del relato occidental, artistas y especialistas de esta parte del mundo intentan identificar y aislar las características que a priori parecen ser exclusivas de la cosmovisión nipona. De más está decir que la empresa es difícil, pues en la aproximación siempre interviene en mayor o menor medida “nuestra occidentalidad”, imposible de erradicar del todo; sin embargo, más que un obstáculo esta deficiencia debería ser causa y razón para intentar un acercamiento riguroso al mundo japonés por medio del conocimiento abierto y sin prejuicios que, en definitiva, es parte esencial del conocimiento científico de Occidente. En uno de sus textos más conocidos, el japonólogo greco-irlandés Lafcadio Hearn, escribe: “Sin el conocimiento de las fábulas populares y de las supersticiones del lejano Oriente, la comprensión de sus novelas, de sus comedias y de sus poesías continuará siendo imposible” (Hearn, El romance de la Vía Láctea: 56). La cita de Hearn es certera, y todo investigador que se haya acercado alguna vez a la literatura o al cine nipones sabrá hasta qué punto es imprescindible este conocimiento que traspasa todos los niveles de una cultura que se niega a abandonar un pasado mítico e histórico-literario del que continúa alimentándose. -

La Mostruosità Nel Giappone Antico E Moderno Dal Folklore Al Cinema, Le Creature Sovrannaturali E La Loro Percezione

Corso di Laurea magistrale (Ordinamento ex D.M. 270/2004) in Lingue e civiltà dell’Asia e dell’Africa Mediterranea Tesi di Laurea La mostruosità nel Giappone antico e moderno Dal folklore al cinema, le creature sovrannaturali e la loro percezione Relatore Ch. Prof. Maria Roberta Novielli Correlatore Ch. Prof. Paola Scrolavezza Laureando Hélène Gregorio Matricola 988023 Anno Accademico 2015 / 2016 1 INDICE ABSTRACT 2 INTRODUZIONE 4 CAPITOLO 1: 1.1 La mostruosità nei testi più antichi e nelle prime forme teatrali 8 1.2 La visione del mostro nel secondo dopoguerra 22 1.3 Da mostruoso a orrorifico 31 CAPITOLO 2: 2.1 L’unicità del Giappone: Yōkaigaku, etnologia e nihonjinron 40 2.2 Tradizione vs modernità: un Giappone dicotomico 54 CAPITOLO 3: 3.1 L’estetica del mostruoso in Honda Ishirō - Gli eredi di King Kong (1968) 67 L’autore 67 La trama del film 70 L’analisi del film 72 3.2 L’estetica del mostruoso in Shimizu Takashi - Juon: Rancore (2002) 80 L’autore 80 La trama del film 83 L’analisi del film 85 3.3 L’estetica del mostruoso in Miike Takashi - The Great Yōkai War (2005) 93 L’autore 93 La trama del film 96 L’analisi del film 98 CONCLUSIONE 107 BIBLIOGRAFIA 110 SITOGRAFIA 113 2 ABSTRACT 昔から人間は言葉で説明出来ない自然現象に興味があった。一番古い史料に基づ くと日本は伊邪那岐命と伊邪那美命と言う神様から創造された群島であることが わかる。古事記や日本書記などにおいては日本の神話起源や神様の偉業や最初の 国王について色々な話が書いてある。その古い史料から超自然的存在のイメージ を分析して、日本民族の為の大切さを解説してみた。別の世界に生きているもの をめぐって昔から現代にかけて様々な言葉が使われている。その言葉の中で化け 物や物の怪や妖怪などが一番古い。時間が経つにつれて他の単語も造語された。 例えば、ある言葉は怪物や怪獣や英語から用いられたモンスターである。すべて の単語の意味はほとんど同じだが、使われている時代とコンテクストは違う。 この卒業論文は3章に分かれている。次に各章の論題を述べていく。 -

TETSUBO Is Copyright © D J Morris & R J Thomson 2010 All Rights Reserved

T E T S U B O TETSUBO is copyright © D J Morris & R J Thomson 2010 all rights reserved Entire contents copyright © Dave Morris & Jamie Thomson 2010 The authors have asserted their moral rights Not for unauthorized distribution TETSUBO is copyright © D J Morris & R J Thomson 2010 all rights reserved TETSUBO by DAVE MORRIS and JAMIE THOMSON With illustrations by Russ Nicholson & Utagawa Kuniyoshi TETSUBO is copyright © D J Morris & R J Thomson 2010 all rights reserved This is a work in progress and therefore incomplete, based on an Oriental supplement that we originally wrote using the Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay rules. Our intention with Tetsubo now is to convert it to the Fabled Lands RPG (itself a work in progress) and modify the setting to Akatsurai, the easternmost country of the Fabled Lands. As well as fully revising the background, we will reinstate the missing sections (marked here in red) and add a scenario section. The new work will then be released as the FL RPG and the first of twelve planned sourcebooks. And yes, we are hoping to do that this lifetime. Other Tetsubo material can be ordered from Robert Rees here. Dave Morris Jamie Thomson TETSUBO is copyright © D J Morris & R J Thomson 2010 all rights reserved Players’ section TETSUBO is copyright © D J Morris & R J Thomson 2010 all rights reserved * CHARACTER RACES * Like the Old World, Yamato has four potential races to which player-characters could belong. However, Yamatese society is not the multi-racial amalgam found in the West. Most Yamatese people have never laid eyes on a nonhuman, and would not want to. -

Yoshitoshi, L'anima Del Passato Come L'esaltazione Dei Soggetti Della Storia Giapponese Trattiene I Valori Tradizionali in Epoca Meiji

Corso di Laurea magistrale (ordinamento ex D.M. 270/2004) in Lingue e civiltà dell'Asia e dell'Africa Mediterranea Tesi di Laurea Yoshitoshi, l'anima del passato Come l'esaltazione dei soggetti della storia giapponese trattiene i valori tradizionali in epoca Meiji Relatore Ch. Prof. Sabrina Rastelli Correlatore Ch. Prof. Marcella Maria Mariotti Laureando Arianna Bianciardi Matricola 827647 Anno Accademico 2014 / 2015 この論文は芳年と伝統の関係についてである。 芳年は幕末から明治前期にかけて活動した浮世絵師として日本や浮世絵にとっ て大変な時代を体験した。 芳年は十二歳で歌川国芳に入門し、目立っていて十五歳の時に自分の処女作が 刊行できた。 創作の初期に先生の様式を真似し、役者絵や武者絵に得意になった。 徳川幕府の権威が低下につれて、日本が内乱で分裂されていった。 とうとう二百年間の鎖国が終わり、開国の時代に入るということになった。 その間に、芳年が「月岡芳年」という画号を用い、「和漢百物語」、「英名二 十八衆句」、「魁題百撰相」、「一魁随筆」という特に残虐なシリーズを描き 始めた。 現在はそのシリーズが「血みどろ絵」と呼ばれ、芳年の制作活動の代表として 見られるようになった。 評論家がこの「血みどろ絵」は芳年がかかっていた精神疾患の原因だと推定す る。 しかし、この論文に明らかにしたいのはその「血みどろ絵」が実際に十年の間 作られていたこともあるし、精神疾患とは無縁だということである。 むしろ、その絵の残虐さが芳年の内側に関連しなく、幕末の違乱とつながって いると思われる。 浮世絵師として当時の問題や日本人の不安を描く、自分や人々の恐れを清めよ うとしたと考えられる。 実はその前後「血みどろ絵」のような非常な残酷さは芳年の錦絵に現れないの で、そのシリーズが有能的に作られたからこそ現在に人気があるだけで、「血 みどろ絵」が芳年の代表的なテーマとして限られるのはあまり客観的な評価で はないとも言える。 かえって芳年の作品の中で不変なモチーフは日本の伝統ということである。 1868年、王政復古で幕府が廃止され、「明治」という新しい時代が始まっ た。 明治時代の目的は欧米を追い、近代化を進ませることだったので江戸時代の伝 統的な絵画である浮世絵が西洋美術の人気で終期に近づいていた。 その時、芳年が日本の精神が消えるという恐れに刺激され、流行を追うどころ か貧困や人気の不足で苦しむまで自分の作品で日本の歴史を保ち、振興するこ とを決めた。 この論文でその選択を分析した後、日本人がどのように身についていない異国 の内容より自分の伝統を受け入れることができ、自分の国の歴史の場面や人物 をと最も同一視できることについて調べようと思っている。 芳年の制作活動はデビューの作品から日本の伝統に影響を受け、その上「血み どろ絵」の人物や場面も日本の歴史に由来する。 芳年が明治時代に入り、心身が衰弱したが、回復してから「大蘇芳年」という 新しい画号に名乗り、新しい時代に賛成しないにもかかわらず進行しようとし た。 以後芳年が二度と残虐なシーンに戻るまい。 回復してから芳年が自分の様式を改良するように西洋美術の遠近法、彩色、陰 -

307429678.Pdf

rsstetttefc ;}jf to REV. EGERTON RYERSON 770,3 6OOO CHINESE CHARACTERS WITH JAPANESE PRONUNCIATIO AND JAPANESE AND ENGLISH RENDERINGS BY J. IRA JONES, A.B. H. V. S. PEEKE, D.D. KYO BUN KWAN TOKYO CONTENTS PAGE PREFACE ... ... ... ... ... v-vi INTRODUCTION vn-ix TABLE OF SOUNDS PRODUCED BY CERTAIN COMBINATIONS OF TWO OR MORE LETTERS OF THE kana ... ... ... ... x LIST OF THE 214 RADICALS ... ... ... XI-XX DICTIONARY 1-212 I.IST OF CHARACTERS WHOSE RADICALS ARE OBSCURE ... ... ... ... ...213-219 LIST OF USEFUL GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES 22O-223 PREFACE. Some years ago the present writer discovered a small Chinese- Japanese dictionary containing five thousand characters. It was fairly well printed, was portable, in fact just what he wanted, but it was nearly out of print. He was fortunate enough to obtain a dozen copies in an obscure book-shop, and made it a practice to pre- sent a copy to young missionaries of special linguistic promise. One of these books was given to Rev. J. Ira Jones, a student missionary at Fukuoka. When Mr. Jones took up the study of the Chinese characters in earnest, he applied the index principle to the little dictionary. There was nothing original in indexing the side margin with numbers for the sets of radicals from one stroke to seventeen. But the indexing of the lower margin for the radicals themselves, thus subdividing the side indexes, deserves the credit of a new invention. By the first, the time required for finding a it addi- character was cut one fourth ; by the second, was reduced an tional two fourths.