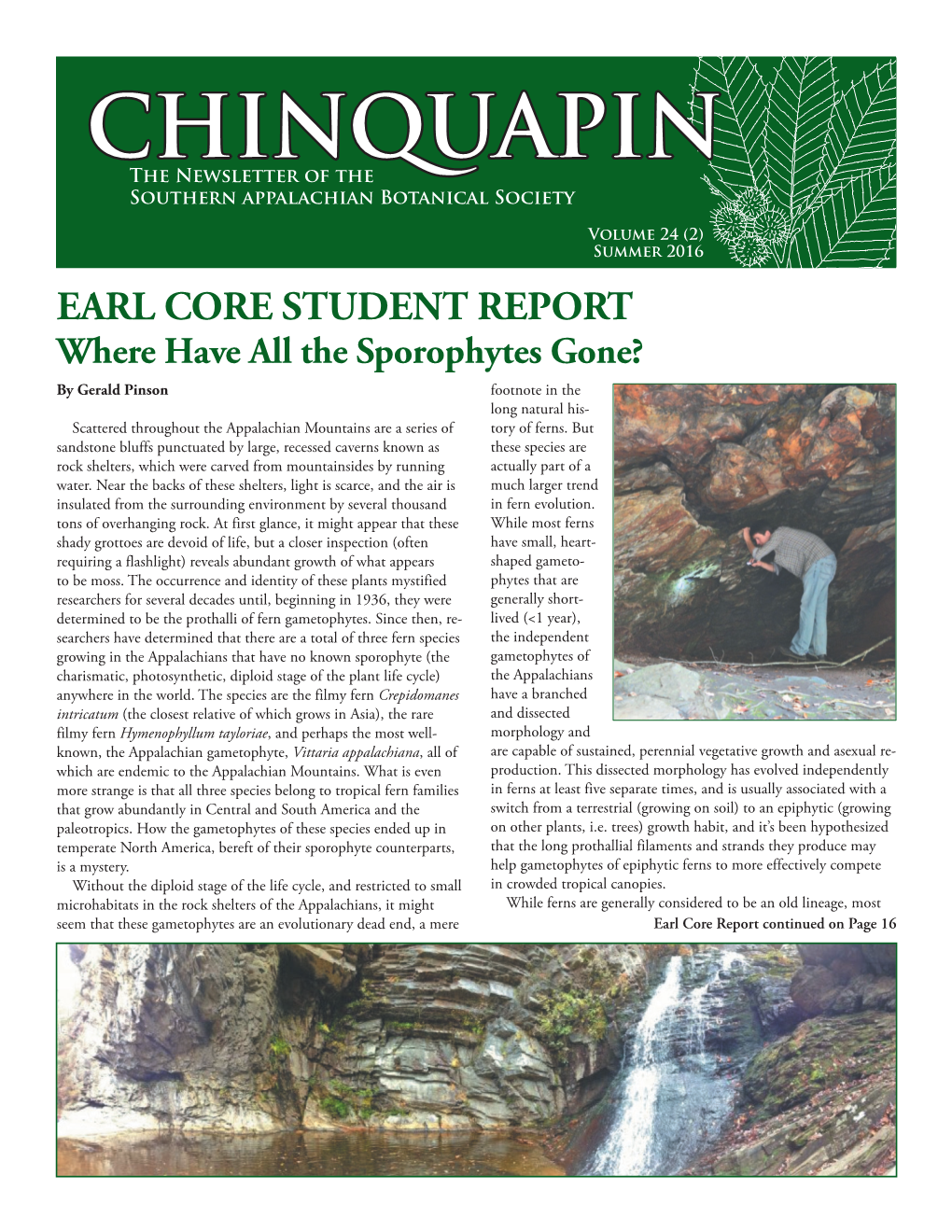

CHINQUAPIN the Newsletter of the Southern Appalachian Botanical Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE Magnoliaceae Liriodendron L. Magnolia L

THE Magnoliaceae Liriodendron L. Magnolia L. VEGETATIVE KEY TO SPECIES IN CULTIVATION Jan De Langhe (1 October 2014 - 28 May 2015) Vegetative identification key. Introduction: This key is based on vegetative characteristics, and therefore also of use when flowers and fruits are absent. - Use a 10× hand lens to evaluate stipular scars, buds and pubescence in general. - Look at the entire plant. Young specimens, shade, and strong shoots give an atypical view. - Beware of hybridisation, especially with plants raised from seed other than wild origin. Taxa treated in this key: see page 10. Questionable/frequently misapplied names: see page 10. Names referred to synonymy: see page 11. References: - JDL herbarium - living specimens, in various arboreta, botanic gardens and collections - literature: De Meyere, D. - (2001) - Enkele notities omtrent Liriodendron tulipifera, L. chinense en hun hybriden in BDB, p.23-40. Hunt, D. - (1998) - Magnolias and their allies, 304p. Bean, W.J. - (1981) - Magnolia in Trees and Shrubs hardy in the British Isles VOL.2, p.641-675. - or online edition Clarke, D.L. - (1988) - Magnolia in Trees and Shrubs hardy in the British Isles supplement, p.318-332. Grimshaw, J. & Bayton, R. - (2009) - Magnolia in New Trees, p.473-506. RHS - (2014) - Magnolia in The Hillier Manual of Trees & Shrubs, p.206-215. Liu, Y.-H., Zeng, Q.-W., Zhou, R.-Z. & Xing, F.-W. - (2004) - Magnolias of China, 391p. Krüssmann, G. - (1977) - Magnolia in Handbuch der Laubgehölze, VOL.3, p.275-288. Meyer, F.G. - (1977) - Magnoliaceae in Flora of North America, VOL.3: online edition Rehder, A. - (1940) - Magnoliaceae in Manual of cultivated trees and shrubs hardy in North America, p.246-253. -

Magnolias of Powell Gardens, Kansas City' S Botanical Garden Ivrfth Notes on Their Cultivation Throughout Greater Kansas City, Missouri and Kansas) Alan Branhagen

ISSUE 79 NIAONOUA Magnolias of Powell Gardens, Kansas City' s Botanical Garden ivrfth notes on their cultivation throughout greater Kansas City, Missouri and Kansas) Alan Branhagen Powell Gardens harbors an extensive collection of Magnolias as they are one of the most spectacular of hardy flowering trees. Visitors will see magnolias displayed throughout the grounds with the biggest vari- ety growing east of the Visitor Center. Many of the newest hybrids are small because landscape-size plants are not yet available from nurser- ies. The goal of the Powell's collections is to display the best ornamen- tal trees for greater Kansas City. Magnolias that perform in our often variable dimate form the core of the collection. Horticulturally, magnolias grow well in greater Kansas City —most thrive in heat and humidity, so it's our severe dry spells in summer and oc- casional and abrupt severe winter cold that is their enemy. Magnolias are forest trees so all do well in the shady understory of woodlands, but many thrive and bloom heaviest in full sun. Oyama and some big- leaf types demand shade in our intense summer sun. Many of our new, small magnolias struggled in the two hot, dry summers of zoo3 and zan. And, one of our biggest problems at Powell Gardens has been with squirrels girdling the stems in late summer and fall. Kansas City's climate is a classic, continental climate. Summers are very hot and humid, with a consistent average high of 89'F (3s.y'c) in July. This heat puts Kansas City in Asrs heat zone 7, along with St. -

Magnolia Fraseri by RTCHARD E

Magnolia fraseri by RTCHARD E. WEAVER, JR. The umbrella magnolias (section Rhytidospermum of Magnolia), are comprised of 8-10 species, variously distributed in the southeastern United States (3-5 species, depending on the taxonomist), the moun- tains of Mexico (2 species) and eastern Asia from the Himalayas through China and Korea to Japan (3 species). The most conspicuous feature of this group are the large leaves clustered at the ends of the branches, simulating an umbrella and accounting for the common name. The species are not currently popular in American horticulture, perhaps because their bad habits are concentrated in Magnolia trzpetala, the most commonly cultivated species and the one to which the name "umbrella magnolia" is often exclusively applied in com- mon usage. With its gaunt habit and undistinguished, ill-scented flowers, this species certainly pales as an ornamental when compared with other magnolias such as M. kobus and its varieties and the numerous cultivars of M. x soulangeana. In addition, the charac- teristic large leaves of the group make the plants somewhat difficult to site effectively in a landscape situation. In the American M. mac- rophylla, for instance, they reach enormous proportions - as much as three feet long and a foot broad, the largest simple leaves of any native woody plant. On the other hand, these large leaves impart to the plants a decidedly unusual and exotic appearance, and several species have 60 61 attractive, fragant flowers followed by large and conspicuous, reddish fruit aggregates. A few species combine these favorable characteris- tics with a refined growth habit, making them first class garden plants worthy of more frequent cultivation. -

One Carolina Dendrological Journey RON LANCE Writes About Some of the Special Species That He Has Found During His Many Expeditions Into the Appalachian Mountains

One Carolina dendrological journey RON LANCE writes about some of the special species that he has found during his many expeditions into the Appalachian Mountains. In every dendrologist’s life, there are memories equivalent to fish tales among fishermen, revelations among artists, crop booms and busts of farmers. We relive catching “big ones” and lament the ones that “got away” from our NH MI NY experiences. Memories of grand MA treks and first acquaintances of CT RI certain trees underscore good years, PA IN OH yet we remember the disasters and NJ MD disappointments associated with our WV DE attention long aimed at trees. We tend KY VA to boast on points of accomplishment, such as being in obscure places whereTN NC notable trees grow, or bringing home significant propagules for SC cultivated collection. Some of us AL GA strive to collect, some merely seek ATLANTIC imagery for experience, and some OCEAN 30 strive to partake of dendrological comradery. Regardless of the how FL and why of tree travels, we all have Eastern United States with framed area tales to tell. (inset) in its detailed form shown opposite. Occupying near the top level of any dendrophile’s fantasy is performing plant exploration and finding something unique. Plant exploration certainly had a golden age when the earth’s corners were new and dendrologists few. Even so, today there are more plant people looking than ever before and we still find new things, and not necessarily things new only to the people looking. I will render a few examples of discoveries highlighting my life, found in my own section of the world tramped so many times before, by hordes of fishermen, hunters, farmers, and a smattering of dendrologists. -

THOMAS WALTER CAROLINA BOTANIST by David H

li\1'7 ~s- .3.e r, t~- J'U>.~ tAf· ,_ f'QIJ ·- • .~ j v b 1980 ST/nT DOCUMENr THOMAS WALTER CAROLINA BOTANIST by David H. Rembert IXpartment ci Biology University of South Carolina Columbia South Carolina -.~ MUSEUM BULLETIN NUMBER 5 SOUTH CAROLINA MUSEUM COMMISSION W~preJ tptnS ~~PJ ~U~preJ tplnS JO Al~WA~Uf1 Afupgpl~ LSINVJDH VNI101IVJ 1ItiL1V& SVWOHL Copyright © 1980 by the South Carolina Museum CommissiOn, Columbia, S. C. 2 • THOMAS WALTER (From a miniature in the possession of a direct descendant, Mrs. Benjamin Arthur Bolt of Greenville, South Carolina) 3 PREFACE Gradually over the last 200 years information has accumulated to illuminate the accomplishments of the early naturalists who visited Colonial South Carolina. These men added greatly to the rapid development of the young, emerging nation and provided the rich inventory of our botanical heritage. One such man was Thomas Walter. It is hoped that this paper will help move this 18th-century botanist a little closer to his rightful place in the annals of science. During the course of this investigation, I have received help and encouragement and it is in that context that I should like to thank the members of the staff at the South Carolina Department of Archives and History and at the South Caroliniana Library for their help. I am also indebted to Mrs. D. Scott, Deputy Librarian at the Herbarium, Kew, England for transcribing the letter from Walter to Mr. William Forsyth and to Mr. John Lewis, PSO at the British Museum of Natural History, for his kindness during my visits there. -

Vascular Covs.Indd

United States Department of Agriculture Vascular Flora of the Fernow Forest Service Experimental Forest and Northeastern Research Station Adjacent Portions of the General Technical Report NE-344 Otter Creek Wilderness Area Robert B. Coxe Steven L. Stephenson Darlene M. Madarish Gary W. Miller Abstract The vascular flora of the region we considered include 94 families representing at least 461 species. Fifty-four of these or nearly 12 percent are species known to have been introduced. Asteraceae (46 species) is the single largest family; Cyperaceae (31), Liliaceae (29), Poaceae and Rosaceae (20 each) also are important families in the general study area. The 461 species of vascular plants recorded constitute only 17.2 percent of the total species (2,683) known from the State of West Virginia but account for a larger proportion (31.5 percent) of all species known from Tucker County or Randolph County. Manuscript received for publication 7 February 2006 Cover Photos Pink lady’s slipper (Cypripedium acaule) and Frasier magnolia (Magnolia fraseri) on the Fernow Experimental Forest. Published by: For additional copies: USDA FOREST SERVICE USDA Forest Service 11 CAMPUS BLVD SUITE 200 Publications Distribution NEWTOWN SQUARE PA 19073-3294 359 Main Road Delaware, OH 43015-8640 September 2006 Fax: (740)368-0152 Visit our homepage at: http://www.fs.fed.us/ne INTRODUCTION Field surveys of the vascular fl ora of the study area described in this report began during the summer of 1994 as part of a project that included establishing 105 permanent plots (each 0.1 ha) in relatively undisturbed forest communities throughout the Fernow Experimental Forest in Tucker County, West Virginia (Muzika et al. -

Druid Hills- Recommended Plant Materials List

9.0 Cultural Landscapes Guidelines - Maintainin Recommendation - The following plant list is intended to assist in the selection of appropriate plant materials. The list has been organized into large trees, small trees, shrubs, annuals/perennials, and vines/ground covers. The list has been developed using the following sources: (1) Olmsted’s Planting List from several plans for Druid Hills; (2) Historic Plants compiled as part of the Georgia Landscapes Project by the Historic Preservation Division of the Georgia Department of Natural Resources; and (3) Native Species. Aggressive exotics have also been noted, so that their use can be limited to controlled situations. (Refer to Section 8.1 Open Space and Parkland Preservation and Conservation: Eradication of Exotic Example of Species.) planting of Bradford Pears Olmsted’s list and the list from the Georgia Landscapes Project provide guidance in selecting materials within intrusion appropriate for historic landscape projects. The Olmsted list has been updated with current plant names. areas within the district. There are other sources that can be consulted to identify additional plants used by Olmsted in Druid Bradford Pear is Hills, such as historic planting plans and, particularly the archival record at the Olmsted National His- nonhistoric tree toric Site in Brookline, Massachusetts. The Olmsted list presented in this document should be considered that would not be a beginning. Residents of Druid Hills are encouraged to add to this list with historic plants that can be appropriate in historic areas of documented as having been used by Olmsted. the district. The native list should be used for natural areas within the district, such as creek corridors and drainage ways. -

Magnolias of the Northeast, Part 2 Steien Cover

ISSUE 76 IVIAGNOUA Magnolias of the Northeast, Part 2 Steien Cover Magnolia kobos Cammen name Kobus Magnolia, Kobushi (in Japan). Other names in literature Magnolia praecocissi ma OeseKutlan A variable species. A small rounded to large upright tree to ySft tall (zz. gm), sometimes multi-trunked, commonly zg —3oft (7.6 — g. tm) tall in cultivation. The 3— gin (y. b-r z. 7cm) wide flowers are abundant on mature plants, white, — and have six petal-like tepals. In zones g 6, flowering occurs before the leaves emerge from mid-April to early May. Leaves are 3— 6in (y. b-zg. zcm) long, the foliage is medium textured. The seed cones are inconspicuous; the bark is smooth and light gray. A handsome and lang-lived tree. Native range/natural hlstmy Widespread throughout Japan, but not known from the island of Shikoku. This tree grows in a wide variety of moist forest types from sea level to over yoooft (SSz4m) in elevation. Plants from the northern island of Hokkaido are reportedly larger and hardier, and are sometimes distinguished in the litera- ture as the var, borealis. Hanliness — U5DA zones y 8. One of the hardiest magnolias. Ornamental value The unenlightened sometimes criticize the plant because the flowers are not enormous, and it can be slow to flower when grown from seed. Nonetheless, it makes a spectacular specimen tree. The white flowers contrast nicely with the gray bark and, at a distance, mature plants look like white clouds when in flower, and have a striking air of purity and simplicity. There is a large M. -

FACTS of SEED COUNTER LIFE - 2013 Read Before Ordering!

FACTS OF SEED COUNTER LIFE - 2013 Read before ordering! Welcome to the Magnolia Society International Seed Counter 2013. This year seed orders will be processed at the Henry Botanic Garden in Gladwyne, PA on March 30th and the seeds mailed on April 1st. Seed orders MUST be received by March 29th - no exceptions will be allowed. So do whatever you need to do to get your order in on time! This year I strongly suggest sending your order by email (see ordering instructions below). Well, it had to happen eventually. This is the smallest seed list I have offered since taking over the Seed Counter in 1997. The cause? Bad luck, mostly. There was simultaneous seed crop failure in many places, including New England. Especially serious for the Seed Counter was the poor seed harvest at Dennis Ledvina’s. Seeds from the Ledvina breeding program and collection have been the heart of the seed list for many years, and their relative absence is keenly felt. Many thanks to all our donors who were able to send in seeds. It is their kindness and generosity that enable all of us to grow such wonderful Magnolias and their efforts are much appreciated. As always, the Seed Counter is grateful to Susan Treadway, who is again hosting the seed distribution at the Henry Botanic Garden and to our precious seed pickers who help on distribution day. Their hard work enables all of you to receive your seeds in a timely fashion. As many of you know, the Seed Counter is a one person operation until the seed distribution day. -

Systematic and Economic Importance of Magnoliaceae: Trees and Shrubs

Systematic and economic importance of Magnoliaceae: Trees and shrubs; two ranked stipulate leaves, stipules enclose young buds; flowers hermaphrodite, actinomorphic, large; perianth usually trimerous, whorled or spiral; stamens and carpels numerous; apocarpous, spirally arranged on elongated axis, fruit an etario of follicles or berries, sometimes samara. A. Vegetative Characters: Habit: Trees or shrubs sometimes climbing. Oil sacks present in stem and leaves. Root: Tap branched. Stem: Erect, aerial, woody, branched. Leaves: Alternate, simple, entire, commonly ever-green, coriaceous, stipules large (Magn•olia) covering young leaves. B. Floral Characters: Inflorescence: Solitary terminal or axillary. Flower: Largest and sometimes, 25 cm in diameter (Magnolia, Fraseri), complete, regular, actinomorphic, unisexual (Drimys), usually bisexual, hypogynous, aromatic. Floral axis (torus) long to long convex. Perianth: Nine to many, free, all alike and petaloid or the three outer ones green (Liriodendron), arranged in whorls of three, imbricate and cyclic (Magnolia and Michelia) or acyclic (spiral) arranged on an elongated or semi-elongated convex torus, free, inferior. Androecium: Stamens many, free, often spirally arranged in a beautiful series, filaments short or absent, anther lobes linear, with a prolonged connective. Gynoecium: Carpels numerous, free, superior, arranged spirally on a cone-shaped elongated thalamus (gynophore), rarely carpels are fused, e.g., Zygogynum, placentation marginal. Fruit: An aggregate of berries or follicles, sometimes, a samara as in Liriodendron Seed: Large, with abundant oily endosperm, and bright or orange testa which makes them highly decorative. Pollination: due to large and scented flowers Floral formula: Distribution of Magnoliaceae: Magnoliaceae or the Magnolia family embraces 10 genera and about 100 species. The members of this family belong to the temperate regions of northern hemisphere, with centres of distribution in eastern Asia, Malaysia, eastern North America, West Indies, Brazil and North-east and south east India. -

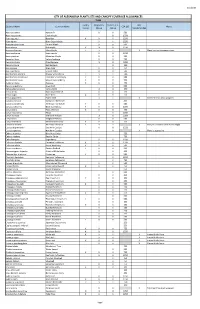

City of Alexandria Plant Lists and Canopy Coverage Allowances Trees

3/1/2019 CITY OF ALEXANDRIA PLANT LISTS AND CANOPY COVERAGE ALLOWANCES TREES Locally Regionally Eastern U.S. Not Botanical Name Common Name CCA (SF) Notes Native Native Native Recommended Abies balsamea Balsam Fir X X 500 Acer leucoderme Chalk Maple X 1250 Acer negundo Boxelder X X X 1250 Acer nigrum Black Sugar Maple X X 1250 Acer pensylvanicum Striped Maple X X 500 Acer rubrum Red maple X X X 1250 Acer saccharinum Silver Maple X X X X Plant has maintenance issues. Acer saccharum Sugar maple X X 1250 Acer spicatum Mountain Maple X X 500 Aesculus flava Yellow Buckeye X X 750 Aesculus glabra Ohio Buckeye X X 1250 Aesculus pavia Red Buckeye X 500 Alnus incana Gray Alder X X 750 Alnus maritima Seaside Alder X X 500 Amelanchier arborea Downy Serviceberry X X X 500 Amelanchier canadensis Canadian Serviceberry X X X 500 Amelanchier laevis Smooth Serviceberry X X X 750 Asimina triloba Pawpaw X X X 750 Betula populifolia Gray Birch X 500 Betula alleghaniensis Yellow Birch X X 750 Betula lenta Black (Sweet) birch X X 750 Betula nigra River birch X X X 750 Betula papyrifera Paper Birch X X X Northern/mountain adapted. Carpinua betulus European Hornbeam 250 Carpinus caroliniana American Hornbeam X X X 500 Carya cordiformis Bitternut Hickory X X X 1250 Carya glabra Pignut Hickory X X X 750 Carya illinoinensis Pecan X 1250 Carya laciniosa Shellbark Hickory X X 1250 Carya ovata Shagbark Hickory X X 500 Carya tomentosa Mockernut Hickory X X X 750 Castanea dentata American Chestnut X X X X Not yet recommended due to Blight Catalpa bignonioides Southern Catalpa X X 1250 Catalpa speciosa Northern Catalpa X X Plant is aggressive. -

Vascular Plant Inventory

VASCULAR PLANT INVENTORY AND PLANT COMMUNITY CLASSIFICATION FOR CARL SANDBURG HOME NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE Report for the Vertebrate and Vascular Plant Inventories: Appalachian Highlands and Cumberland/Piedmont Networks Prepared by NatureServe for the National Park Service Southeast Regional Office February 2003 NatureServe is a non-profit organization providing the scientific knowledge that forms the basis for effective conservation action. A NatureServe Technical Report Prepared for the National Park Service under Cooperative Agreement H 5028 01 0435. Citation: White, Jr., Rickie D. 2003. Vascular Plant Inventory and Plant Community Classification for Carl Sandburg Home National Historic Site. NatureServe: Durham, North Carolina. © 2003 NatureServe NatureServe 6114 Fayetteville Road, Suite 109 Durham, NC 27713 919-484-7857 International Headquarters 1101 Wilson Boulevard, 15th Floor Arlington, Virginia 22209 www.natureserve.org National Park Service Southeast Regional Office Atlanta Federal Center 1924 Building 100 Alabama St., S.W. Atlanta, GA 30303 404-562-3163 The view and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not consitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. This report consists of the main report along with a series of appendices with information about the plants and plant communities found at the site. Electronic files have been provided to the National Park Service in addition to hard copies. Current information on all communities described here can be found on NatureServe Explorer at www.natureserve.org/explorer. Cover photo: Close-up of a flower of the pink lady’s slipper (Cypripedium acaule) in an oak-hickory forest at Carl Sandburg Home National Historic Site.