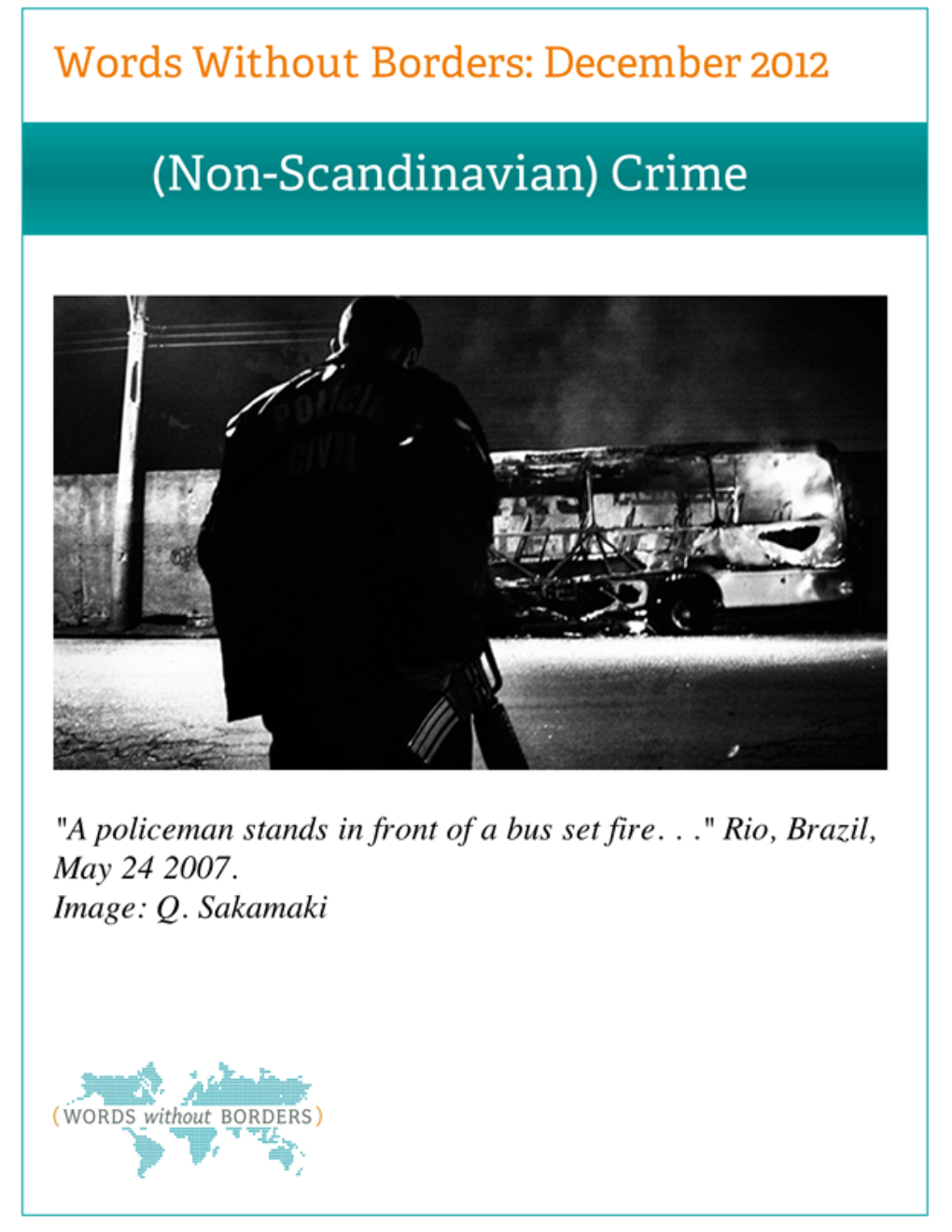

Nonscandanavian Crime

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fiction Matters 2016

THE NEWSLETTER OF THE INTERNATIONAL DUBLIN LITERARY AWARD FICTION MATTERS No.22 – February 2016 THE COMPLETE LIST OF ELIGIBLE TITLES 2016 SHORTLIST ANNOUNCEMent 12 April WINNER ANNOUNCEMent 9 June www.dublinliteraryaward.ie Harvest by Jim Crace is the winner of the 20th Award! The 2015 Winner Announcement took place in the Round Room of the Mansion House, Dublin on 17th June 2015 Left to Right; Margaret Hayes, Dublin City Librarian; Jim Crace, winner of the 2015 award; Lord Mayor of Dublin and Patron of the Award, Christy Burke; Owen Keegan, Chief Executive, Dublin City Council. The International DUBLIN Literary Award (formerly IMPAC Dublin) is presented annually for a novel written in English or translated into English. The award aims to promote excellence in world literature and is sponsored by Dublin City Council, the municipal government of Dublin. The award is now in its 21st year. Nominations are submitted by library systems in major cities throughout the world. 2 www.dublinliteraryaward.ie Kate Harvey from Picador – publishers of Harvest – is presented with a Jane Alger, Director, Dublin UNESCO City Dublin Crystal Bowl by Owen Keegan, Chief Executive, Dublin City Council, with of Literature, Master of Ceremonies. Jim Crace, right. Jim Crace, pictured with Alessandra Mariani, Biblioteca Margaret Hayes, Dublin City Librarian, pictured here with Nazionale di Roma, Italy, as she is presented with a scroll by the Kantawan Magkunthod, winner of the Thai Young Writers Lord Mayor, Christy Burke, in recognition of library participation competition, organised by the Irish Embassy in Malaysia. worldwide. Congratulations to the nominators of Harvest, Universitätsbibliothek Bern, Switzerland and LeRoy Collins Leon County Public Library System, Tallahassee, USA. -

FICTION MATTERS No 21 — February 2015

THE NEWSLETTER OF THE INTERNATIONAL IMPAC DUBLIN LITERARY AWARD FICTION MATTERS No 21 — February 2015 INTERNATIONAL IMPAC DUBLIN LITERARY AWARD 2015 COMPLETE LIST OF ELIGIBLE TITLES Shortlist Announcement 15th April 2015 Winner Announcement 17th June 2015 www.impacdublinaward.ie The Sound of Things Falling by Juan Gabriel Vásquez, translated from Spanish by Anne McLean, is the Winner of the 2014 Award Photo: Jason Clarke Photography Jason Photo: (L-R) Margaret Hayes, Dublin City Librarian; Lord Mayor of Dublin and Patron of the Award, Christy Burke; Juan Gabriel Vásquez, winner of the 2014 award; Anne McLean, translator; Owen Keegan, Chief Executive, Dublin City Council. Photo: Jason Clarke Photography Jason Photo: Clarke Photography Jason Photo: Bill Swainson (right), Bloomsbury Publishing, publishers of The Sound of Jane Alger, Director Dublin UNESCO City of Literature and Things Falling, is presented with a Dublin Crystal bowl by Owen Keegan, the winner, Juan Gabriel Vásquez, pictured here with members of Dublin Chief Executive, Dublin City Council. Fire Brigade holding the City of Dublin Sword and Mace. The 2014 Winner Announcement took place in the Round Room of the Mansion House, Dublin, 12th June 2014 Photo: Jason Clarke Photography Jason Photo: Clarke Photography Jason Photo: Giles Foden, judge 2014 award, is presented with a scroll by the Lord Mayor, Dawn Beaumont (left), Library of Birmingham, UK, is presented with a Christy Burke. The judging panel also included Tash Aw, Catherine Dunne, scroll by Margaret Hayes, Dublin City Librarian, in recognition of library Maya Jaggi, Maciej Świerkocki and Judge Eugene Sullivan (non-voting participation worldwide. chair). Photo: Jason Clarke Photography Jason Photo: Congratulations to Biblioteca Daniel Cosío Villegas, El Colegio de México, nominators of The Sound of Things Falling. -

Translation and Literature Cumulative Index Volume 30

Translation and Literature Cumulative Index Volume 30 (2021) Part 2 Articles and Notes A. S. G. Edwards: Gavin Bone and his Old English Translations Mary Boyle: ‘Hardly gear for woman to meddle with’: Kriemhild’s Violence in Nineteenth- Century Women’s Versions of the Nibelungenlied Andrew Barker: Giant Bug or Monstrous Vermin? Translating Kafka’s Die Verwandlung in its Cultural, Social, and Biological Contexts Review Essay Caroline Batten and Charles Tolkien-Gillett: Translating Beowulf for our Times Reviews Gideon Nisbet: After Fame: The Epigrams of Martial, by Sam Riviere Sarah Carter: Ovid and Adaptation in Early Modern English Theatre, edited by Lisa S. Starks; Ovidian Transversions: Iphis and Ianthe, 1300-1650, edited by Valerie Traub, Patricia Badir, and Peggy McCracken Carla Suthren: Xenophon: Cyropaedia, translated by William Barker, edited by Jane Grogan James Simpson: The Song of Roland: A Verse Translation, by Anthony Mortimer Jonathan Evans: Zola and the Art of Television: Adaptation, Recreation, Translation, by Kate Griffiths Ritchie Robertson: Karl Kraus: The Third Walpurgis Night: The Complete Text, translated by Fred Bridgham and Edward Timms Enza De Francisci: Celebrity Translation in British Theatre: Relevance and Reception, Voice and Visibility, by Robert Stock Catherine Davies: Ten Contemporary Spanish Women Poets, edited and translated by Terence Dooley Céline Sabiron: Translation et violence, by Tiphaine Samoyault Marjorie Huet-Martin: Textuality and Translation, edited by Catherine Chavin and Céline Sabiron Volume -

Apoio À Edição No Estrangeiro

Apoio à Edição no Estrangeiro 37 ÁFRICA DO SUL Short Stories from Dicionário dos Mozambique Anglicismos e Die Horen - Org. Richard Bartlett Germanismos na Portugiesische Joanesburgo, Cosaw Língua Portuguesa Literatur Publishing, 1995, 278 p., Jürgen Schimidt-Radefeldt/ (Revista) inglês Dorothea Schurig AAVV ISBN: 0 -620-19726-9 Frankfurt, TFM, 1997, Bremerhaven, Die Horen, 298 p., português 1999, 244 p. ISBN: 3 -925203-48-6 ALEMANHA Erdbeden von Lissabon Duplicate – Leonor und der Chronologisches Antunes Katastrophendiskus im Ästhetik der Texte - Lexikon der (Catálogo da Exposição) Varietät von Sparche 18.Jahrhundert (Das) portugugiesischen AAVV AAVV Org. Cornelia Klettke, Literatur Berlim, Künstlerhaus Coord. Gerhard Lauer/ António C. Franco, Ilídio Rocha Bethanien, 2005, 67 p. il., Thorsten Unger Gunther Frankfurt, TFM, 1999, alemão/inglês Göttingen, Wallstein Verlag, Hammermüller 328 p. ISBN: 3 -932754-66-2 2008, 608 p., il. Tubingen, Gunter Narr ISBN: 3 -925203-62-1 ISBN: 978-3-8353-0267-9 Verlag, 2000, 334 p., ISBN: 3 -8233-5203-2 Con-Con 2003. Constructed Connections Gedichte und Prosa (Catálogo da Exposição) Deutschland und die Manuel Alegre AAVV überseeische Ferruccio Busoni - Trad. Sarita Brandt Trad. Rebeccah Blum/ Expansion Portugals Vianna da Motta. Frankfurt, TFM, 1998, 177 Briefwechsel 1898-1921 Julika Gittner im 15. und 16. p., português/alemão Jahrhundert Org. Christine Wassermann ISBN: 3 -925203-57-4 Munique, Verlag Silke Beirão Schreiber, 2003, 59 p., il. Jürgen Pohle Munique, Lit Verlag, Wilhelmshaven, Florian ISBN: 3 -88960-067-0 Noetzel Verlag, 214 p. 1999, 322 p. ISBN: 3 -7959-0833-7 ISBN: 3 -8258-4376-9 38 Geschlechterdiskurse in Gesprochenes Guide de la Littérature der Modernen Literatur Gestohlene Diamant Geschichte Portugals Portugiesisch Portugaise Brasiliens, Portugals, Maria de Fátima Viegas (Der) Org. -

The Nature of Translated Text — an Interdisciplinary Methodology for the Investigation of the Specific Properties of Translations

The Nature of Translated Text — An Interdisciplinary Methodology for the Investigation of the Specific Properties of Translations Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Philosophie der Philosophischen Fakult¨aten der Universit¨at des Saarlandes vorgelegt von Silvia Hansen Saarbr¨ucken, im Dezember 2002 II Tag der letzten Promotionsleistung: 3. Dezember 2002 Dekan der Philosophischen Fakult¨atII: Prof. Dr. Erich Steiner Berichterstatter: Prof. Dr. Erich Steiner Berichterstatterin: PD Dr. Elke Teich Preface Wenn du eine Stunde gl¨ucklich sein willst, schlafe! Wenn du einen Tag gl¨ucklich sein willst, geh fischen! Wenn du ein Jahr gl¨ucklich sein willst, habe ein Verm¨ogen! Wenn du ein Leben gl¨ucklich sein willst, liebe deine Arbeit! Chinesische Weisheit1 Als ich dieses Sprichwort zum ersten Mal las, habe ich mir Gedanken dar¨uber gemacht, wie sehr mir das, was ich seit einiger Zeit als meine Arbeit be- zeichne, wirklich gef¨allt. Zuerst schoss mir dabei der Gedanke durch den Kopf, dass ich meine Arbeit w¨ahrend der Promotion mehr gehasst als gemocht habe. Wahrscheinlich wissen alle, die etwas ¨ahnliches durchge- standen haben, was ich damit meine. Genauso wahrscheinlich ist, dass allen Promovierenden das schlechte Gewissen bekannt ist, das sich zu jeder Tages- und Nachtzeit sowie unabh¨angig von Jahreszeiten einstellt, wenn man sich mit irgendetwas besch¨aftigt, das nicht mit der Dissertation zu tun hat. Dabei spielt nat¨urlich der Zeitfaktor eine besondere Rolle: Aus eigener Erfahrung kann ich mittlerweile schlussfolgern, dass W¨orter wie Freizeit oder Urlaub ihre Bedeutung verlieren, wenn man sich einbildet, man k¨onnte w¨ahrendder Promotion, die nach M¨oglichkeit innerhalb von drei Jahren zu absolvieren ist, einer Ganztags-Besch¨aftigung nachgehen. -

Translation and the Reader: a Survey of British Book Group Members’ Attitudes Towards Translation

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Translation and the Reader: A Survey of British Book Group Members’ Attitudes towards Translation Catherine Campbell PhD University of Edinburgh Department of Translation Studies 2015 DECLARATION This is to certify that that the work contained within has been composed by me and is entirely my own work. No part of this thesis has been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. Signed: Catherine Campbell 19th August 2015 ABSTRACT In commercial book translation, the reader is the end-user of the translated text; it is for his or her benefit that the translation has been produced, and it is the reading public whose money ultimately goes towards paying the translator‘s wages. Nonetheless, in Translation Studies, far more attention has been paid to the processes of translation or the finished translation product (see Saldanha and O‘Brien 2013) than to the users of such products, with reader-based studies few and far between. -

Author List for Advertisers This Is the Master Set of Authors Currently Available to Be Used As Target Values for Your Ads on Goodreads

Author List for Advertisers This is the master set of authors currently available to be used as target values for your ads on Goodreads. Use CTRL-F to search for your author by name. Please work with your Account Manager to ensure that your campaign has a sufficient set of targets to achieve desired reach. Contact your account manager, or [email protected] with any questions. 'Aidh bin Abdullah Al-Qarni A.G. Lafley A.O. Peart 029 (Oniku) A.G. Riddle A.O. Scott 37 Signals A.H. Tammsaare A.P.J. Abdul Kalam 50 Cent A.H.T. Levi A.R. Braunmuller A&E Kirk A.J. Church A.R. Kahler A. American A.J. Rose A.R. Morlan A. Elizabeth Delany A.J. Thomas A.R. Torre A. Igoni Barrett A.J. Aalto A.R. Von A. Lee Martinez A.J. Ayer A.R. Winters A. Manette Ansay A.J. Banner A.R. Wise A. Meredith Walters A.J. Bennett A.S. Byatt A. Merritt A.J. Betts A.S. King A. Michael Matin A.J. Butcher A.S. Oren A. Roger Merrill A.J. Carella A.S.A. Harrison A. Scott Berg A.J. Cronin A.T. Hatto A. Walton Litz A.J. Downey A.V. Miller A. Zavarelli A.J. Harmon A.W. Exley A.A. Aguirre A.J. Hartley A.W. Hartoin A.A. Attanasio A.J. Jacobs A.W. Tozer A.A. Milne A.J. Jarrett A.W. Wheen A.A. Navis A.J. Krailsheimer Aaron Alexovich A.B. Guthrie Jr. A.J. -

Tools for Extinction

Lolli Editions 132 Defoe House, Barbican EC2Y 8ND London [email protected] lollieditions.com Tools for Extinction Lolli Editions brings 18 international writers together in response to Covid-19 With contributions by Enrique Vila-Matas, Olivia Sudjic, Inger Wold Lund, Vi Khi Nao, Patrícia Portela, Jon Fosse, Michael Salu, Lucie Elven, Mara Coson, Christina Hesselholdt, Jean-Baptiste Del Amo, Naja Marie Aidt, Joanna Walsh, Frode Grytten Anna Zett, Emilio Fraia, Olga Ravn, and Jakuta Alikavazovic Publication: 21 May 2020 Description: 200 × 130 mm, 120 pages, softcover ISBN: 978-1-9999928-2-8 Design: Ard – Chuard and Nørregaard Price: £17 1 Lolli Editions 132 Defoe House, Barbican EC2Y 8ND London [email protected] lollieditions.com About the anthology In Tools for Extinction, 18 writers from across the globe answer to the open-ended period of social distancing, closures, and illness caused by Covid-19. Compiled during the initial lockdown in Europe, this special collection is a meteoric publishing project with contributions from some of the most exciting, innovative, and celebrated authors working today. Meditating on notions of distance and closeness, sameness and alterity, extinguishing and kindling, the book considers how a common pause might give rise to new modes of domesticity and shift experiences of time. What gestures and actions are we willing to perform to make ourselves, and each other, feel at ease – or at work? What tools and objects are useful, or unprecedentedly useless, to us in the process? And as our species’ trademark proclivity for projecting ourselves into the future is disrupted, might we come to see the buildings, animals, plants and foodstuffs around us in a new light? Translations by Margaret Jull Costa, Zoë Perry, Martin Aitken, Denise Newman, Paul Russell Garrett, Damion Searls, and Rahul Bery Compiled, edited and with a foreword by Denise Rose Hansen. -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY Abate, Carmine, Between Two Seas , trans. by Antony Shugaar (2002; New York: Europa Editions, 2008). Abdolah, Kader, My Father’s Notebook , trans. by Susan Massotty (2000; Edinburgh: Canongate, 2007). Aboulela, Leila, The Translator , new edn (1999; Edinburgh: Polygon, 2008). Achebe, Chinua, Things Fall Apart , new edn (1958; Oxford: Heinemann Educational Publishers, 1986). Adamovich, Ales, Khatyn , trans. by Glenys Kozlov, Frances Longman and Sharon McKee (1972; London: Glagoslav Publications, 2012). Adelson, Leslie A., ‘Coordinates of Orientation: An Introduction’, in Zafer Şenocak, Atlas of a Tropical Germany: Essays on Politics and Culture, 1990–1998 , trans. and edited by Leslie A. Adelson (1992; Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2000), xi–xxxvii. ———, ‘Against Between: A Manifesto’, New Perspectives on Turkey , Vol. 29 (2003), 19–36. ———, The Turkish Turn in Contemporary German Literature: Toward a New Critical Grammar of Migration (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005). Adesokan, Akin, ‘New African Writing and the Question of Audience’, Research in African Literatures , Vol. 43, No. 3 (2012), 1–20. Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi, Purple Hibiscus (New York: Algonquin Books, 2003). ———, ‘The Danger of a Single Story’ (2009), TED , http://www.ted.com/ talks/chimamanda_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story.html (accessed 17 September 2015). Adnan, Etel, Paris, When It’s Naked (Sausalito: The Post-Apollo Press, 1993). © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 301 A. Hammond (ed.), The Novel and Europe, DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-52627-4 302 BIBLIOGRAPHY Adorno, Theodor W., ‘Cultural Criticism and Society’ (1967), in Adorno, Prisms , trans. by Samuel M. Weber (1955; Cambridge: MIT Press, 1983), 17–34. ———, Gesammelte Schriften (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1998). -

Jaarverslag 2014 Nederlands Letterenfonds

ederlands N letterenfonds dutch foundation for literature Jaar- verslag 2014 1 Investeren in de letteren 4 Het Letterenfonds in het binnenland 8 De Nederlandse literatuur over de grenzen 10 Bijzondere projecten en samenwerkingsverbanden 13 Evaluatie en kwaliteitsbeleid 15 Vooruitzichten 16 Bestuur & beheer 20 Bijlage 1: Verslag Raad van Toezicht 2014 23 Bijlage 2: Bureau en Raad van advies per 31 december 2014 29 Bijlage 3: Toekenningen 2014 58 Bijlage 4: Prijzen 61 Bijlage 5: Activiteiten 2014 70 Bijlage 6: Publicaties, websites en social media 72 Bijlage 7: Balans & exploitatierekening 75 Bijlage 8: Private stichtingen 77 Colofon Uitgelicht / Highlights: 3, 6, 12, 19, 60, 76 Summary Annual Report 2014 The Dutch Foundation for Literature stimulates the quality and diversity of literature by means of grants and subsidies for writers, translators, publishers and festivals, and contributes to the propagation and promotion of Dutch- and Frisian-language literature at home and abroad. In 2014, thanks in part to the Dutch Foundation for Literature, more than three hundred literary projects were initiated, in all the literary genres: novels, stories, biographies, literary non-fiction, children’s and young adult literature, and poetry. The Foundation supported 174 high-quality translations of foreign titles into Dutch and 120 new works by Dutch authors. The value of the new Dutch- language work by writers supported by the Foundation, including many young talents, is reflected in the nominations and awards garnered by their books. Over the past year, almost four hundred translations of Dutch literary works were published abroad after direct mediation and active promotion by the Foundation, 192 of them with financial support for the publishers and translators. -

Jaarverslag 2013 Nederlands Letterenfonds

ederlands N letterenfonds dutch foundation for literature Jaar- verslag 2013 Het Letterenfonds in tien vragen Binnenkant cover 3 Investeren in de letteren 5 Het Letterenfonds in het binnenland 8 Intussen in het buitenland 11 Vooruitzichten 14 Bestuur en beheer 18 Bijlagen Het Letterenfonds in tien vragen 3. En daarom zijn jullie met velen? We zitten in het Letterenhuis aan de Nieuwe Prinsen- gracht, een oude kweekschool met een gymzaal die verbouwd is tot bibliotheek, gevuld met onder meer een unieke collectie (deels) door het Fonds gesubsidieerde vertalingen van Nederlandse literatuur in andere talen. We verhuren de helft van de ruimte aan Nationaal Comité 4 en 5 mei en aan twee instanties waarmee we veel Vier jaar geleden ontstond het Nederlands samenwerken: Schrijvers School Samenleving en Stich- Letterenfonds, uit een fusie van het Fonds voor de ting Lezen. En ja, we zijn op dit moment nog met meer Letteren en het Nederlands Literair Productie- en dan dertig, inclusief parttimers; we onderscheiden ons Vertalingenfonds. Wat doet dit publiek gefinancierde van de meeste andere publieke cultuurfondsen doordat cultuurfonds? Een (nadere) kennismaking in tien we ook de buitenlandse promotie als kerntaak hebben pertinente vragen. en doordat we – behalve bij een handvol grote festivals (zoals Poetry International, Crossing Border en Passio- 1. Het Letterenfonds, dat is toch de instantie die nate Bulkboek) – met verhoudingsgewijs kleine investe- de schrijverssubsidies verdeelt? ringen al veel verschil kunnen maken. Budgettair is het Jazeker, maar het Fonds doet veel meer. Een vijfde van Letterenfonds het kleinste publieke cultuurfonds, maar ons budget, ongeveer twee miljoen euro, wordt besteed dat geldt niet voor het aantal activiteiten dat we initiëren aan projectsubsidies voor oorspronkelijk werk, dat wil en uitvoeren: het Fonds organiseert wereldwijd ook zelf zeggen aan investeringen in nieuwe romans, verhalen- regelmatig evenementen, festivals en themapresentaties. -

Annotated Books Received

ANNOTATED BOOKS RECEIVED TABLE OF CONTENTS Translation Studies.............................................................33 Literary Works Index of Translators ..........................................................35 Anthologies..........................................................................1 Directory of Publishers ......................................................37 Reprints ................................................................................3 Arabic...................................................................................4 LITERARY WORKS Babylonian ...........................................................................4 Bengali. ................................................................................4 ANTHOLOGIES Bulgarian..............................................................................5 Chinese.................................................................................5 (French) Belgian Women Poets: An Anthology. Ed. and tr. Estonian................................................................................5 Renée Linkhorn and Judy Cochran. New York. Peter Lang. French...................................................................................6 2000. 479 pp. Cloth: $72.95; ISBN 0-8204-4456-1. Belgian German................................................................................ 9 Francophone Library, Vol. 11. Bilingual. Designed to Greek..................................................................................11 acquaint an English-speaking