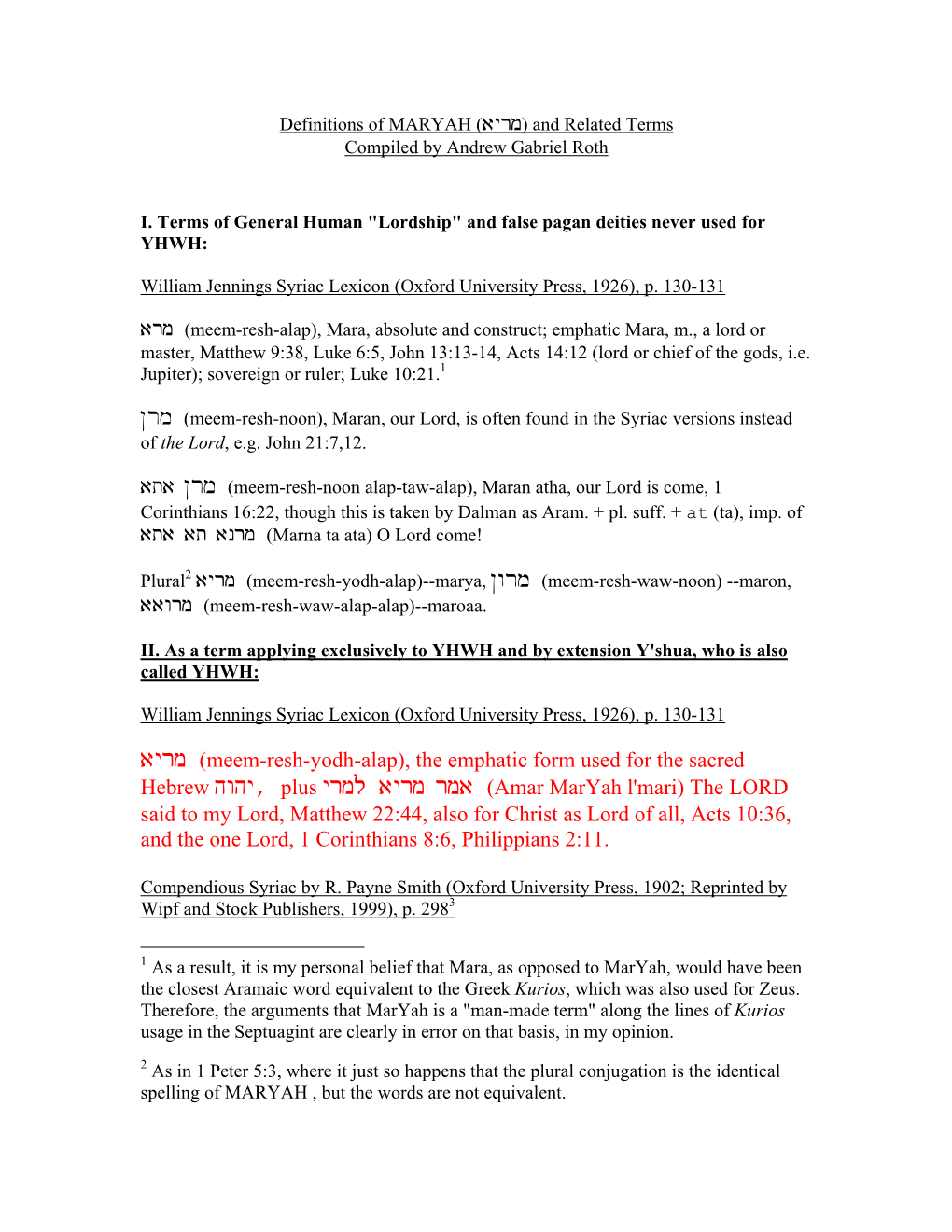

Ayrm (Meem-Resh-Yodh-Alap), the Emphatic Form Used for the Sacred

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Torah from JTS Worship, JTS

Exploring Prayer :(בלה תדובע) Service of the Heart This week’s column was written by Rabbi Samuel Barth, senior lecturer in Liturgy and Torah from JTS Worship, JTS. Simhat Torah: Which Way When the Circle Ends Bereishit 5774 The annual celebration of Simhat Torah brings great joy to so many of us of all generations, and it is a fitting and triumphant conclusion to the long and multifaceted season of intense Jewish observance and focus that began (a little before Rosh Hashanah) with Selichot. In Israel and in congregations observing a single day of festivals, Simhat Torah is blended with Shemini Atzeret, offering the intense experience in the morning of Hallel, Hakkafot (processions with dancing) and Geshem (the prayer for Rain). At the morning service of Simhat Torah there are four linked biblical readings (three from the Parashah Commentary Torah), and the relationship among them invites us to think about the flow of sacred text in a multidimensional context. The first reading is Vezot HaBrakha, the last chapters of Deuteronomy This week’s commentary was written by Dr. David Marcus, professor of Bible, containing the final blessings from Moses to the community—and the account of the death of Moses, alone with God on Mount Nebo. To receive the final aliyah after everyone else present JTS. has been called to the Torah is considered a great honor, and the person with this honor is called up with a special formula (a short version is presented in Siddur Sim Shalom for Shabbat Bereishit with a Capital Bet and Festivals, 215) that affirms, “May it be the will of the One Most Powerful to grant abundant blessings to [insert the name of the one called] who has been chosen to complete the Torah.” With this week’s parashah, we once again commence the cycle of reading the Torah from the first chapter of Genesis, which begins with the Hebrew word bereishit. -

ב Bet ה Heh ו Vav ט Tet י Yod ך מ Mem ם

Exercise 1A: Writing the Hebrew Square Script Using the examples at the right, practice writing out the Hebrew characters on the lines provided for you. Be sure to accurately reflect the position of the letter in relation to the base line. Boxes are used to indicate final forms. Letter Name aleph א aleph bet ב bet gimel ג gimel dalet ד dalet heh ה heh vav ו vav zayin ז zayin .het ח ḥet tet ט tet yod י kaph כ yod ך kaph final kaph lamed ל mem מ lamed ם mem 3 Exercise 1A: Writing tHe Hebrew SquAre Script final mem Letter Name nun נ ן nun final nun samek ס samek ayin ע pe פ ayin ף pe final pe tsade צ ץ tsade final tsade qoph ק qoph resh ר resh שׂ sin sin shin ׁש shin tav ת tav NAme: __________________________________________________ Exercise 1A: Writing tHe Hebrew SquAre Script 4 Exercise 1B: Reading Proper Names In this exercise you will practice identifying the Hebrew consonants by reading familiar proper names. Write the English name in the space to the left of the Hebrew name. Since the alphabet has no vowels, you will have to provide vowel sounds to recognize each word. Start by trying an “a” vowel between each con- sonant. The “a” vowel is the most common vowel in Hebrew and, while it will not always be the correct one, it should help you recognize these names. לבן Laban יעקב אסתר אברהם עבדיה יצחק יחזקאל יׂשראל דוד רבקה נחמיה נבכדנאזר ירבעם ירדן מרדכי מׁשה דברה גלית יׁשמעאל עׂשו 5 Exercise 1B: ReAding Proper NAmes Exercise 1C: Hebrew Cursive (Optional) Using the examples shown, practice writing out the cursive Hebrew characters on the lines provided for you. -

Rayut / Sacred Companionship: the Art of Being Human Rabbi Steven Kushner Rosh Hashanah Morning 5771

Rayut / Sacred Companionship: the art of being human Rabbi Steven Kushner Rosh Hashanah Morning 5771 It’s a ‘‘sweet-sixteen’’ party. The grandmother, who personally related this story to me, notices that her 16-year-old granddaughter is sitting at a table, smart-phone in hand, busily typing away with her thumbs. ‘‘What are you doing?’’ the grandmother asks. ‘‘I’m texting my best friend,’’ the granddaughter replies. ‘‘Just a minute,’’ the grandmother objects. ‘‘Do you mean to tell me you didn’t invite your best friend to your sweet-sixteen party?’’ ‘‘Of course I did,’’ the granddaughter replies. ‘‘She’s sitting right over there.’’ Does this sound familiar? Do you have kids who now use their thumbs to talk, even when vocal communication is not merely possible but easier? That, of course, is the question. Does modern technology make communication easier------with cell phones, text messaging, twittering, emailing------or does it actually make it more complex? This dynamic, of impersonal electronic talking, should be alarming to us. Forget the fact that we’ve lost the ability to write longhand. (Kids, your parents will tell you what ‘‘longhand’’ means after the service.) Never mind that we’ve abandoned the beautiful art form of ‘‘correspondence’’. (My brother and I still have all the letters my parents wrote to each other during World War II.) No matter that we’ve forgotten what it’s like to have to wait to get to a gas station to call someone on the phone. The consequences of instant non-verbal communication may be, even in the short-term, devastating. -

How Was the Dageš in Biblical Hebrew Pronounced and Why Is It There? Geoffrey Khan

1 pronounced and why is it בָּתִּ ים How was the dageš in Biblical Hebrew there? Geoffrey Khan houses’ is generally presented as an enigma in‘ בָּתִּ ים The dageš in the Biblical Hebrew plural form descriptions of the language. A wide variety of opinions about it have been expressed in Biblical Hebrew textbooks, reference grammars and the scholarly literature, but many of these are speculative without any direct or comparative evidence. One of the aims of this article is to examine the evidence for the way the dageš was pronounced in this word in sources that give us direct access to the Tiberian Masoretic reading tradition. A second aim is to propose a reason why the word has a dageš on the basis of comparative evidence within Biblical Hebrew reading traditions and other Semitic languages. בָּתִּיםבָּתִּ ים The Pronunciation of the Dageš in .1.0 The Tiberian vocalization signs and accents were created by the Masoretes of Tiberias in the early Islamic period to record an oral tradition of reading. There is evidence that this reading tradition had its roots in the Second Temple period, although some features of it appear to have developed at later periods. 1 The Tiberian reading was regarded in the Middle Ages as the most prestigious and authoritative tradition. On account of the authoritative status of the reading, great efforts were made by the Tiberian Masoretes to fix the tradition in a standardized form. There remained, nevertheless, some degree of variation in reading and sign notation in the Tiberian Masoretic school. By the end of the Masoretic period in the 10 th century C.E. -

The Christological Aspects of Hebrew Ideograms Kristološki Vidiki Hebrejskih Ideogramov

1027 Pregledni znanstveni članek/Article (1.02) Bogoslovni vestnik/Theological Quarterly 79 (2019) 4, 1027—1038 Besedilo prejeto/Received:09/2019; sprejeto/Accepted:10/2019 UDK/UDC: 811.411.16'02 DOI: https://doi.org/10.34291/BV2019/04/Petrovic Predrag Petrović The Christological Aspects of Hebrew Ideograms Kristološki vidiki hebrejskih ideogramov Abstract: The linguistic form of the Hebrew Old Testament retained its ancient ideo- gram values included in the mystical directions and meanings originating from the divine way of addressing people. As such, the Old Hebrew alphabet has remained a true lexical treasure of the God-established mysteries of the ecclesiological way of existence. The ideographic meanings of the Old Hebrew language represent the form of a mystagogy through which God spoke to the Old Testament fathers about the mysteries of the divine creation, maintenance, and future re-creation of the world. Thus, the importance of the ideogram is reflected not only in the recognition of the Christological elements embedded in the very structure of the Old Testament narrative, but also in the ever-present working structure of the existence of the world initiated by the divine economy of salvation. In this way both the Old Testament and the New Testament Israelites testify to the historici- zing character of the divine will by which the world was created and by which God in an ecclesiological way is changing and re-creating the world. Keywords: Old Testament, old Hebrew language, ideograms, mystagogy, Word of God, God (the Father), Holy Spirit, Christology, ecclesiology, Gospel, Revelation Povzetek: Jezikovna oblika hebrejske Stare Zaveze je obdržala svoje starodavne ideogramske vrednote, vključene v mistagoške smeri in pomene, nastale iz božjega načina nagovarjanja ljudi. -

Hebrew Names and Name Authority in Library Catalogs by Daniel D

Hebrew Names and Name Authority in Library Catalogs by Daniel D. Stuhlman BHL, BA, MS LS, MHL In support of the Doctor of Hebrew Literature degree Jewish University of America Skokie, IL 2004 Page 1 Abstract Hebrew Names and Name Authority in Library Catalogs By Daniel D. Stuhlman, BA, BHL, MS LS, MHL Because of the differences in alphabets, entering Hebrew names and words in English works has always been a challenge. The Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) is the source for many names both in American, Jewish and European society. This work examines given names, starting with theophoric names in the Bible, then continues with other names from the Bible and contemporary sources. The list of theophoric names is comprehensive. The other names are chosen from library catalogs and the personal records of the author. Hebrew names present challenges because of the variety of pronunciations. The same name is transliterated differently for a writer in Yiddish and Hebrew, but Yiddish names are not covered in this document. Family names are included only as they relate to the study of given names. One chapter deals with why Jacob and Joseph start with “J.” Transliteration tables from many sources are included for comparison purposes. Because parents may give any name they desire, there can be no absolute rules for using Hebrew names in English (or Latin character) library catalogs. When the cataloger can not find the Latin letter version of a name that the author prefers, the cataloger uses the rules for systematic Romanization. Through the use of rules and the understanding of the history of orthography, a library research can find the materials needed. -

Biblical Hebrew: Dialects and Linguistic Variation ——

ENCYCLOPEDIA OF HEBREW LANGUAGE AND LINGUISTICS Volume 1 A–F General Editor Geoffrey Khan Associate Editors Shmuel Bolokzy Steven E. Fassberg Gary A. Rendsburg Aaron D. Rubin Ora R. Schwarzwald Tamar Zewi LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 © 2013 Koninklijke Brill NV ISBN 978-90-04-17642-3 Table of Contents Volume One Introduction ........................................................................................................................ vii List of Contributors ............................................................................................................ ix Transcription Tables ........................................................................................................... xiii Articles A-F ......................................................................................................................... 1 Volume Two Transcription Tables ........................................................................................................... vii Articles G-O ........................................................................................................................ 1 Volume Three Transcription Tables ........................................................................................................... vii Articles P-Z ......................................................................................................................... 1 Volume Four Transcription Tables ........................................................................................................... vii Index -

PUBLICATIONS of GEOFFREY KHAN BOOKS 1 Studies in Semitic

PUBLICATIONS OF GEOFFREY KHAN BOOKS 1 Studies in Semitic Syntax (Oxford University Press, 1988), 252pp. 2. Karaite Bible Manuscripts from the Cairo Genizah (Cambridge University Press, 1990), 186pp. 3. Arabic Papyri: Selected material from the Khalili Collection (Oxford University Press, 1992), 264pp. 4. Arabic Legal and Administrative Documents in the Cambridge Genizah Collections (Cambridge University Press, 1993), 567pp. 5 Bills, Letters and Deeds. Arabic papyri of the seventh-eleventh centuries (Oxford University Press, 1993), 292pp. 6. A Grammar of Neo-Aramaic. The dialect of the Jews of Arbel (Brill, Leiden, 1999), 586pp. 7. The Early Karaite Tradition of Hebrew Grammatical Thought: Including a Critical Edition, Translation and Analysis of the Diqduq of ʾAbū Yaʿqūb Yūsuf ibn Nūḥ (Brill, Leiden, 2000), 581pp. 8. Early Karaite Grammatical Texts (Scholars Press, Atlanta, 2000), 357pp. 9. Exegesis and Grammar in Medieval Karaite Texts, editor, Journal of Semitic Studies Supplement Series 13, Oxford, 2001, 239pp. 10. The Neo-Aramaic Dialect of Qaraqosh (Brill, Leiden, 2002), 750pp. 11. The Karaite Tradition of Hebrew Grammatical Thought in its Classical Form: A Critical Edition and English Translation of al-Kitāb al-Kāfī fī al-Lugha al-ʿIbrāniyya by ʾAbū al-Faraj Hārūn ibn al-Faraj (Brill, Leiden, 2003). In collaboration with María Ángeles Gallego and Judith Olszowy-Schlanger, 1097pp. 12. The Jewish Neo-Aramaic Dialect of Sulemaniyya and Ḥalabja (Brill, Leiden, 2004), 619pp. 13. Semitic Studies in Honour of Edward Ullendorff, editor (Brill, Leiden, 2005), 367pp. 14. Arabic Documents from Early Islamic Khurasan (Nour Foundation, London, 2008), 183pp. 15. The Neo-Aramaic Dialect of Barwar. 3 vols. Vol. -

P:\00000 Ussc\17-432

NO. 17-432 In the Supreme Court of the United States CHINA AGRITECH, INC., Petitioner, v. MICHAEL H. RESH, et al., Respondents. On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit BRIEF IN OPPOSITION BETSY C. MANIFOLD MATTHEW M. GUINEY WOLF HALDENSTEIN ADLER Counsel of Record FREEMAN & HERZ LLP WOLF HALDENSTEIN ADLER 750 B Street, Suite 2770 FREEMAN & HERZ LLP San Diego, California 92101 270 Madison Avenue 619.239.4590 New York, New York 10016 212.545.4600 DAVID A.P. BROWER [email protected] BROWER PIVEN A Professional Corporation 475 Park Avenue South, 33rd Floor New York, New York 10016 212.501.9000 Attorneys for Respondents William Schoenke, Heroca Holding, B.V., and Ninella Beheer, B.V. Becker Gallagher · Cincinnati, OH · Washington, D.C. · 800.890.5001 i COUNTER-STATEMENT OF THE QUESTION PRESENTED In American Pipe & Construction Co. v. Utah, 414 U.S. 538 (1974), this Court held that “the commencement of a class action suspends the applicable statute of limitations as to all asserted members of the class who would have been parties had the suit been permitted to continue as a class action.” (Emphasis added). The question presented is: Whether plaintiffs whose individual claims are timely as a result of American Pipe tolling may also bring those claims in a subsequent class action on behalf of all class members whose claims are also timely as a result of American Pipe tolling. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS COUNTER-STATEMENT OF THE QUESTION PRESENTED ................. i TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.................. iv INTRODUCTION........................... 1 STATEMENT OF THE CASE ................ -

Grammar Chapter 1.Pdf

4 A Modern Grammar for Biblical Hebrew CHAPTER 1 THE HEBREW ALPHABET AND VOWELS Aleph) and the last) א The Hebrew alphabet consists entirely of consonants, the first being -Shin) were originally counted as one let) שׁ Sin) and) שׂ Taw). It has 23 letters, but) ת being ter, and thus it is sometimes said to have 22 letters. It is written from right to left, so that in -is last. The standard script for bibli שׁ is first and the letter א the letter ,אשׁ the word written cal Hebrew is called the square or Aramaic script. A. The Consonants 1. The Letters of the Alphabet Table 1.1. The Hebrew Alphabet Qoph ק Mem 19 מ Zayin 13 ז Aleph 7 א 1 Resh ר Nun 20 נ Heth 14 ח Beth 8 ב 2 Sin שׂ Samek 21 ס Teth 15 ט Gimel 9 ג 3 Shin שׁ Ayin 22 ע Yod 16 י Daleth 10 ד 4 Taw ת Pe 23 פ Kaph 17 כ Hey 11 ה 5 Tsade צ Lamed 18 ל Waw 12 ו 6 To master the Hebrew alphabet, first learn the signs, their names, and their alphabetical or- der. Do not be concerned with the phonetic values of the letters at this time. 2. Letters with Final Forms Five letters have final forms. Whenever one of these letters is the last letter in a word, it is written in its final form rather than its normal form. For example, the final form of Tsade is It is important to realize that the letter itself is the same; it is simply written .(צ contrast) ץ differently if it is the last letter in the word. -

50 Names of God Hebrew Letters (*Note: All Letters Are Listed As We Read Them in Latin – Left to Right

50 Names of God Hebrew Letters (*Note: all letters are listed as we read them in Latin – left to right. When writing them in Hebrew, the first letter should be written starting from the right.) 1. Eheieh aleph-he-yod-he 2. Iah yod-he 3. Yahvé yod-he-vav-he 4. El aleph-lamed 5. Elohim Gibor aleph-lamed-he-yod-mem gimel-beth-vav-resh 6. Eloha ve Da-ath aleph-lamed-vav-he vav-dalet-ayin-tet-he 7. Yahvé Tzebaot yod-he-vav-he tzade-beth-aleph-vav-tav 8. Elohim Tzebaot aleph-lamed-he-yod-mem tzade-beth-aleph-vav-tav 9. Shadaï El-Haï shin-dalet-yod aleph-lamed hre-yod 10. Adonaï Melek aleph-dalet-nun-yod mem-lamed-kaf 1. Kether kaf-tav-resh 2. Hokmah he-kaf-mem-he 3. Binah beth-yod-nun-he 4. Hesed hre-samech-dalet 5. Geburah gimel-beth-vav-resh-aleph-he 6. Tipheret tav-phe-aleph-resh-tav 7. Netzah nun-tzade-hre 8. Hod he-vav-dalet 9. Yesod yod-samech-vav-dalet 10. Malkut mem-lamed-kaf-vav-tav 1. Metatron mem-tet-tet-resh-vav-nun 2. Raziel resh-zayin-yod-aleph-lamed 3. Tzaphkiel tzade-phe-qof-yod-aleph-lamed 4. Tzadkiel tzade-dalet-qof-yod-aleph-lamed 5. Kamael kaf-mem-aleph-lamed 6. Mikael mem-yod-kaf-aleph-lamed 7. Haniel he-nun-yod-aleph-lamed 8. Raphael resh-phe-aleph-lamed 9. Gabriel gimel-beth-resh-yod-aleph-lamed 10. Sandalphon samech-nun-dalet-lamed-phe-vav-nun 1. -

Learn Assyrian Online the Aramaic Alphabetsyriac-Aramaic Vocabulary

LEARN ASSYRIAN ONLINE THE ARAMAIC ALPHABETSYRIAC-ARAMAIC VOCABULARY 11/10/06 Grab a sheet of lined paper, review the pronounciation, and practice each A-TOOTAA (letter) 10 times, and educate yourself. Along with knowledge comes pride. Along with pride comes confidence. Confidence in yourself reflects the confidence people have in you. With pride, confidence, and knowledge, our nation will survive for 100 more generations. Remember, as one of the first Christians (a couple years after the life of Christ), you speak one of the oldest, rarest languages in the world. The language of God!!! Be proud of that. It is the root language of Hebrew, Arabic, and the alphabet for Greek, Farsi (Persian), Georgian, Turkish (uighur script) which also begat the Mongolean script.)) Aramaic replaced our ancient brethren's language, Akkadian (the oldest semetic language) around 1000 B.C.. The aramaic script was in turn derived from the Phonecians who probably extracted it from Canaan. After the Assyrians accepted the language of the Aramaens, Aramaic became the lingua franca of Mesopotamia and the whole Middle-East. The word Aramaic comes from the word Aram, the son of Shem, of which the word SHE-MAA-YAA (Semetic) is derived. There are two major dialects, Western (also refered to as APalastinian dialect@ (the dialect of EE- SHO (Jesus)) and Eastern (also referred to as "Syriac dialect" ("Syriac" is a dialect of Aramaic, not a language)). To say Modern Aramaic or Modern Syriac, you must be consistent and say Modern Hebrew, Modern English, Modern Greek, etc. for all languages follow the law of evolution.