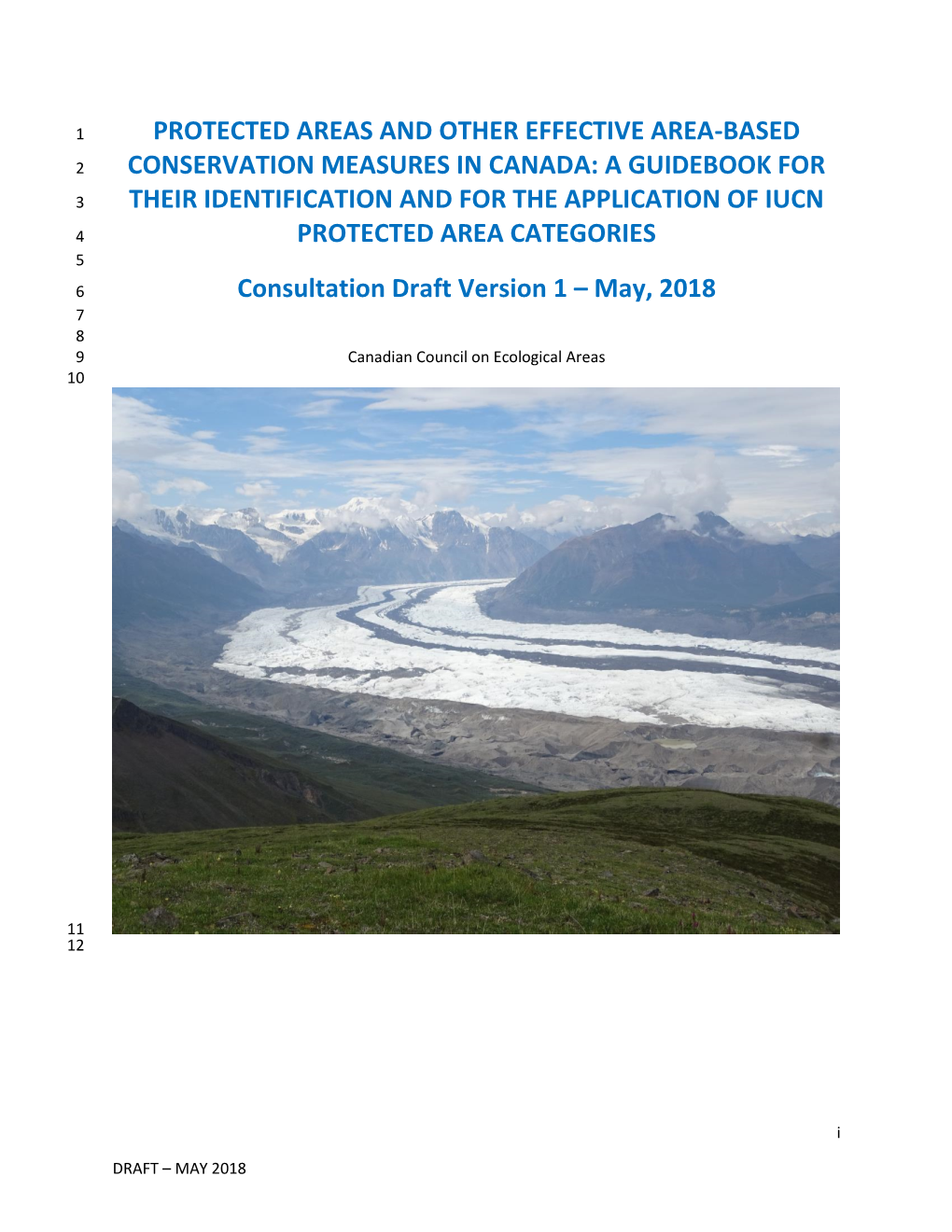

Protected Areas and Other Effective Area-Based Conservation Measures in Canada: a Guidebook for Their Identification and For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geocaching: Using Technology As a National Historic Site’S World Heritage Sirmilik and Ukkusiksalik Means to a Great Experience

parks canada agency Words to Action a p r i l 2 0 0 8 www.pc.gc.ca Cover Photos Background image (front and back): Kluane National Park and Reserve of Canada, J.F. Bergeron/ENVIROFOTO, 2000 Featured Images (left to right, top to bottom): Prince Albert National Park of Canada, W. Lynch, 1997; Gros Morne National Park of Canada, Michael Burzynski, 2001; Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Site of Canada, Chris Reardon, 2006; Parkdale Fire Station, Parks Canada Inside Cover Photo S. Munn, 2000 Amended (July, 2008) Words to Action Table of Contents INTRODUctiON . 1 PARKS CANADA’S RELAtiONShipS With FAciLitAtiNG ViSitOR EXPERIENCE . 39 ABORIGINAL PEOPLES . 23 Explorer Quotient: CONSERVAtiON OF Healing Broken Connections at Personalizing Visitor Experiences . .41 CULTURAL RESOURCES . 3 Kluane National Park and Making Personal Connections Hands-on History . 4 Reserve of Canada . 24 Through Interpretation . 43 Celebrating the Rideau Canal Inuit Knowledge at Auyuittuq, Geocaching: Using Technology as a National Historic Site’s World Heritage Sirmilik and Ukkusiksalik Means to a Great Experience . 45 National Parks of Canada . 25 Designation . 5 Planning for Great Visitor Experiences: Enhancing the System of National Employment Program: The Visitor Experience Assessment . 47 Enhancing Aboriginal Employment Historic Sites . 7 Opportunities . 26 A Role in the Lives of Today’s CONTActiNG PARKS CANADA . 49 Communities: Parkdale Fire Station . 10 Presentation of Aboriginal Themes: Aboriginal Interpretation Innovation Sahoyúé §ehdacho National Historic Fund . 27 Site of Canada: A Sacred Place . 11 Commemoration of Aboriginal History . 29 PROTEctiON OF NATURAL RESOURCES . 13 Establishing New National Parks OUTREAch EDUCAtiON . 31 and National Marine Conservation Areas . -

KANADA ALASKA MIT YUKON IHR KANADA UND ALASKA Dieser Katalog Enthält Nur Eine Auswahl an Rundreisen in Kanada Und Alaska

April 2021 bis März 2022 KANADA ALASKA MIT YUKON IHR KANADA UND ALASKA Dieser Katalog enthält nur eine Auswahl an Rundreisen in Kanada und Alaska. Jede Reise passen wir gerne auf Ihre individuellen Bedürfnisse an. Weitere Angebote finden Sie auf travelhouse.ch und wir beraten Sie gerne persönlich in unseren Reisebüros. INHALTSVERZEICHNIS WILLKOMMEN BEI KANADA 6–107 MOTORHOMES 133–139 TRAVELHOUSE Rundreisen ................................................. 7–14 Informationen ......................................... 133–135 Ihr Schweizer Spezialist Motorhome-Rundreisen ................................ 15–17 Fraserway RV Rentals ................................ 136–137 für besondere Reiseerlebnisse ............................ 2–3 Bahnreisen ................................................ 18–19 GoNorth ............................................... 138–139 Mietwagenrundreisen .................................. 20–63 Bärenbeobachtungen ................................... 64–66 Erlebnisreisen ............................................ 67–71 MIETWAGEN 140–144 British Columbia inkl. Vancouver Island ........... 72–79 Ausflüge ........................................................73 Alamo ......................................................... 140 Vancouver ................................................ 74–76 National ...................................................... 141 Alberta .................................................... 80–84 Hertz ......................................................... 142 Calgary ................................................... -

Preparing World Heritage Nominations (First Edition, 2010) Published in February 2011 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

FIRST EDITION, 2010 PREPARING WORLD HERITAGE Resource Manual NOMINATIONS World Heritage World Heritage Convention For more information contact: UNESCO World Heritage Centre 7, place de Fontenoy 75352 Paris 07 SP France Tel: 33 (0)1 45 68 18 76 Fax: 33 (0)1 45 68 55 70 E-mail: [email protected] World Heritage http://whc.unesco.org Convention international council on monuments and sites Original Title: Preparing World Heritage Nominations (First Edition, 2010) Published in February 2011 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO, ICCROM, ICOMOS and IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The UNESCO World Heritage Centre, ICCROM, ICOMOS, IUCN and other participating organizations disclaim any errors or omissions in the translation of this manual from the original version in English, or from primary errors in any of the data interpreted within it. This manual has taken as a reference the most recent version of the Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention (2008). Currently, the Operational Guidelines are being revised and will be approved by the World Heritage Committee at its 35th session in June 2011. An updated version of this manual will be published afterwards. Free non-profit use/reproduction of this -

North America 2020

North America Including Canada 2020 cosmos.co.uk “And just like that, my bucket list got shorter.” No one turns dream trips into reality with more expertise and affordability than Cosmos. With more than 50 years of sharing the world with value-minded travellers like you, we’ll help you turn your bucket list into a “better-than-I-dreamed” list. From Europe’s grand cathedrals to the cathedral walls of the Grand Canyon; from Britain’s cobblestones to California’s Pebble Beach; from the “City of Light” to “The City that Never Sleeps,” there’s no end to what you can dream. From the Amazon River to the Americana of Route 66; from the Australian Outback to the Inside Passage of Alaska, there’s no end to the ways you can make your travel dreams come true. Whether you’re wishing for a walk through the temples of Thailand or the tidal pools of the Galapagos Islands, we take you to the world’s most amazing places, including treasures to be found in North America’s backyard. 2 Dreams meet Doable With more than 50 years of sharing the world with Director; guided sightseeing of must-see sights; and savvy travellers who answer adventure’s call, we seamless transportation that makes getting there know why you travel. We know that another day in half the fun! From Alaska to Australia, and almost an amazing destination means more to you than every place in between, our expertly planned, a fancy chocolate on your pillow! Cosmos travel easy-to-afford, and even easier-to-enjoy holidays experts still insist that you enjoy comfortable, turn “wish I could” into -

Paleontologists for a Day, a New Way to Discover Miguasha National Park

Contract 400119680 ESTABLISHED • MAY 1975 VOLUME 44 / NO 31 / AUGUST 8, 2018 $1.50 (Tax included) Paleontologists for a day, a new way to discover Miguasha National Park Gilles Gagné million years ago, When we see many fish trapped in the MIGUASHA – A new activity rock in the same direction, it initiated on July 11 by the probably means that there was Miguasha National Park, On some strong current in that the traces of a paleontologist, area, that they were facing that started with a rare finding, as a current,” explains Jason. 12-year-old boy from Quebec About two hours into the City, Raphaël Bolduc, found visit, the group finds another the tail of a Miguashaia bu- interesting fossil, a placoderm, reaui, a fish belonging to a a fish whose bones formed an group called the actinistians. armour around the body. “It is It was only the 30th such a very primitive type of fish,” fish to join the collection of points out Jason. The imprints 14,000 specimens of fossils of the bones left conspicuous belonging to the Miguasha traces in the rock. Park. Raphaël found the tail of Sandra Houle, the mother the Miguashaia bureaui during of Jacob and Raphaël, says the first 30 minutes of a new that the couple chose that visit guided activity led by Jason “because the boys are very cu- Willett. rious about fossils.” For decades, visitors have Her husband Philippe also been welcomed to walk along liked the three-hour visit quite the cliffs of the Miguasha Park a lot. “For the people inter- and learn from the technicians ested in new experiments, it is and paleontologists, as they very, very good.” are working on the field in Jason Willett and Jacob Bolduc watch Raphaël Bolduc examine his find under a microscope. -

Quebec Für Einsteigerinnen

Impressum Herausgeberin: Yvonne Völkl Redaktion: Verena Bachinger Christiane Klamminger Michaela Köppl Katharina Mrak Stephanie Peterseil David Zottler Umschlaggestaltung: Yvonne Völkl Graz 2009 Yvonne Völkl (Hg.) Quebec für EinsteigerInnen Ein Handbuch von Studierenden für Studierende Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorwort ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Allgemein Wissenswertes Québécois, das etwas andere Französisch.................................................................................. 5 Verena Pallier Der Personentransport in der kanadischen Provinz Quebec .................................................... 15 Michaela Köppl Au secours! – Notfallmaßnahmen, Telefonnummern und öffentlicher Dienst in Montreal .... 25 Ingeborg Jandl Studieren in der Provinz Quebec Étudier au Québec: Ein studentischer Reiseführer durch die bürokratischen Ver(w)irrungen 38 Carina Windhager Wohnen in Quebec leicht gemacht........................................................................................... 49 Martina Maier Universitäten in Montreal......................................................................................................... 60 Stephanie Peterseil Kulturelle Genüsse innerhalb und außerhalb der Île de Montréal Eine Reise durch das Stadtleben in Montreal........................................................................... 71 Andrea Jesse Vieux-Montréal, ein Altstadtviertel voller Kunstgenüsse....................................................... -

Världsarvets Villkor

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS STOCKHOLMIENSIS Stockholm Studies in Ethnology 1 Världsarvets villkor Världsarvets villkor Intressen, förhandlingar och bruk i internationell politik Jan Turtinen Stockholms universitet Omslagsbild: Unescos världsarvskarta 2006. © Unesco World Heritage Centre. © Jan Turtinen, Stockholm 2006 ISSN 1653-851X ISBN 91-85445-41-X Tryck US-AB, Stockholm 2006 Distributör: Almqvist & Wiksell International, Stockholm. Till mor och far Innehåll Förord..............................................................................................................9 1. Inledning....................................................................................................11 Ett globalt räddningsprojekt och dess förutsättningar..................................................11 Globalisering, internationalisering och transnationella processer................................16 Byråkrati......................................................................................................................21 Förhandlingar..............................................................................................................22 Skärningspunkter – kulturarv, politik, nätverk och marknad ........................................24 Världsarv – tidigare forskning......................................................................................26 Translokal etnografi.....................................................................................................29 Etik i studiet av politik..................................................................................................38 -

English/French

World Heritage 32 COM Distribution Limited WHC-08/32.COM/INF.1 Paris, 17 March 2008 Original: English/French UNITED NATIONS EDUCATIONAL, SCIENTIFIC AND CULTURAL ORGANIZATION CONVENTION CONCERNING THE PROTECTION OF THE WORLD CULTURAL AND NATURAL HERITAGE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE Thirty second Session Quebec City, Canada 2 – 10 July 2008 GENERAL INFORMATION For complete information on the 32nd session, please visit the following Web site: www.Canada2008.ca This Web site has links to the necessary information regarding registration forms, visa requirements, travel advice and recommended accommodation, and tourist information. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. PURPOSE............................................................................................................ 4 2. SESSION ORGANIZERS..................................................................................... 4 3. PARTICIPANTS AND REGISTRATION ............................................................... 5 3.1 Participants................................................................................................... 5 3.2 Registration .................................................................................................. 5 4. ACCOMMODATION............................................................................................. 6 5. PASSPORT, VISA AND OTHER TRAVEL INFORMATION................................. 7 5.1 Information About Travelling to Canada ....................................................... 7 5.2 Passport Requirements............................................................................... -

Die Ökonomische Dimension Des UNESCO-Welterbes – Ein Wirt- Schaftspolitischer Diskurs

Die ökonomische Dimension des UNESCO-Welterbes – ein wirt- schaftspolitischer Diskurs INAUGURALDISSERTATION zur Erlangung der Würde eines Doktors der Wirtschaftswissenschaft der Fakultät für Wirtschaftswissenschaft der Ruhr-Universität Bochum vorgelegt von Diplom-Ökonomin Ann-Katrin Voit aus Bochum 2017 Dekan: Prof. Dr. Helmut Karl Referent: Prof. Dr. Helmut Karl Korreferent: Prof. Dr. Jörg Schimmelpfennig Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 18.10.2017 “Si no escalas la montaña jamás podrás contemplar el paisaje” Pablo Neruda (Chilenischer Schriftsteller) Inhaltsverzeichnis Abkürzungsverzeichnis ............................................................................. VIII 1. Einleitung ................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Problemstellung und Zielsetzung ................................................................... 1 1.2 Vorgehensweise ............................................................................................. 3 2. Voraussetzungen für den Erwerb des Welterbe-Status ........................... 5 2.1 Vorbemerkungen ............................................................................................ 5 2.2 Der Nominierungs- und Ernennungsprozess .................................................. 8 2.3 Rechte und Pflichten im Zusammenhang mit einer Welterbestätte ........... 17 2.4 Der Begriff Welterbe, Welterbeliste und die Rahmenbedingungen ............ 19 2.5 Institutionen rund um das Welterbe ........................................................... -

Bas-Saint-Laurent Gaspésie Côte-Nord – Manicouagan Côte-Nord – Duplessis Îles De La Madeleine

PRESS KIT Beautiful by Nature ! Bas-Saint-Laurent Gaspésie Côte-Nord – Manicouagan Côte-Nord – Duplessis Îles de la Madeleine anali ©Pietro C ©Pietro www.quebecmaritime.ca Explore Québec maritime… PRESENTATION 3 DID YOU KNOW THAT… 4 NATIONAL PARKS 5 WILDLIFE OBSERVATION 7 WINTER ACTIVITIES 8 LODGING 10 GASTRONOMY 14 REGIONAL AMBASSADORS 17 EVENTS 20 STORY IDEAS 24 QUÉBEC MARITIME PHOTO LIBRARY 28 CONTACT AND SOCIAL MEDIA 29 Le Québec maritime 418 724-7889 84, Saint-Germain Est, bureau 205 418 724-7278 Rimouski (Québec) G5L 1A6 @ www.quebecmaritime.ca Presentation Located in Eastern Québec, Québec maritime is made up of the easternmost tourist regions in the province, which are united by the sea and a common tradition. These regions are Bas-Saint-Laurent, Gaspésie, Côte-Nord (Manicouagan and Duplessis) and the Îles de la Madeleine. A vast territory bordered by 3000 kilometres (1900 miles) of coastline, which alternates between wide fine- sand beaches and small, rocky bays or impressive cliffs, Québec maritime has a long tradition that has been shaped by the ever-present sea. This tradition is expressed in the lighthouses that dot the coast, diverse and abundant wildlife, colourfully painted houses, gatherings on the quays and especially the joie de vivre of local residents. There are places you have to see, feel and experience… Québec maritime is one of them! www.quebecmaritime.ca/evenements34 Did You Know That… • The tallest lighthouse in Canada is in Cap-des-Rosiers and is 34 metres (112 feet) high? • Jacques Cartier named the Lower North Shore “the land of many isles” because this region’s islands were too numerous to name individually? • Lake Pohénégamook is said to hide a monster named Ponik? • The Manicouagan impact crater is the fifth largest in the world and can be seen from space? • Legendary Percé Rock had three arches in Jacques Cartier’s time? • The award winning movie Seducing Dr. -

Miguasha National Park - 2014 Conservation Outlook Assessment (Archived)

IUCN World Heritage Outlook: https://worldheritageoutlook.iucn.org/ Miguasha National Park - 2014 Conservation Outlook Assessment (archived) IUCN Conservation Outlook Assessment 2014 (archived) Finalised on 12 November 2014 Please note: this is an archived Conservation Outlook Assessment for Miguasha National Park. To access the most up-to-date Conservation Outlook Assessment for this site, please visit https://www.worldheritageoutlook.iucn.org. Miguasha National Park عقوملا تامولعم Country: Canada Inscribed in: 1999 Criteria: (viii) The palaeontological site of Miguasha National Park, in south-eastern Quebec on the southern coast of the Gaspé peninsula, is considered to be the world's most outstanding illustration of the Devonian Period known as the 'Age of Fishes'. Dating from 370 million years ago, the Upper Devonian Escuminac Formation represented here contains five of the six fossil fish groups associated with this period. Its significance stems from the discovery there of the highest number and best-preserved fossil specimens of the lobe- finned fishes that gave rise to the first four-legged, air-breathing terrestrial vertebrates – the tetrapods. © UNESCO صخلملا 2014 Conservation Outlook Good The conservation outlook for the Miguasha National Park is good and presents no cause for concern. The current state of the geological values and attributes of the property is good and the trend is stable. New fossil discoveries are being made as a result of continuing field investigation, and an active research program is yielding new insights into the evolution of fishes and amphibians in Devonian times. The property is essentially secure and there are no significant threats to its outstanding universal values or attributes. -

2017 Conservation Outlook Assessment (Archived)

IUCN World Heritage Outlook: https://worldheritageoutlook.iucn.org/ Miguasha National Park - 2017 Conservation Outlook Assessment (archived) IUCN Conservation Outlook Assessment 2017 (archived) Finalised on 09 November 2017 Please note: this is an archived Conservation Outlook Assessment for Miguasha National Park. To access the most up-to-date Conservation Outlook Assessment for this site, please visit https://www.worldheritageoutlook.iucn.org. Miguasha National Park SITE INFORMATION Country: Canada Inscribed in: 1999 Criteria: (viii) Site description: The palaeontological site of Miguasha National Park, in south-eastern Quebec on the southern coast of the Gaspé peninsula, is considered to be the world's most outstanding illustration of the Devonian Period known as the 'Age of Fishes'. Dating from 370 million years ago, the Upper Devonian Escuminac Formation represented here contains five of the six fossil fish groups associated with this period. Its significance stems from the discovery there of the highest number and best-preserved fossil specimens of the lobe-finned fishes that gave rise to the first four-legged, air-breathing terrestrial vertebrates – the tetrapods. © UNESCO IUCN World Heritage Outlook: https://worldheritageoutlook.iucn.org/ Miguasha National Park - 2017 Conservation Outlook Assessment (archived) SUMMARY 2017 Conservation Outlook Good The conservation outlook for the Miguasha National Park is good and presents no immediate cause for concern. The current state of the geological values and attributes of the property is good and the trend is stable. New fossil discoveries are being made as a result of continuing field investigation, and an active research program is yielding new insights into the evolution of fishes and earl< tetrapods in Devonian times.