Law at Mcgill: Past, Present and Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Judicial Function Under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms Anne F Bayefsky

The Judicial Function under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms Anne F Bayefsky* The author surveys the various American L'auteur resume les differentes theories am6- theories of judicial review in an attempt to ricaines du contr61e judiciaire dans le but de suggest approaches to a Canadian theory of sugg6rer une th6orie canadienne du r8le des the role of the judiciary under the Canadian juges sous Ia Charte canadiennedes droits et Charter of Rights and Freedoms. A detailed libert~s. Notamment, une 6tude d6taille de examination of the legislative histories of sec- 'histoire 1fgislative des articles 1, 52 et 33 de ]a Charte d6montre que les r~dacteurs ont tions 1, 52 and 33 of the Charterreveals that voulu aller au-delA de la Dclarationcana- the drafters intended to move beyond the Ca- dienne des droits et 6liminer le principe de ]a nadianBill ofRights and away from the prin- souverainet6 parlementaire. Cette intention ciple of parliamentary sovereignty. This ne se trouvant pas incorpor6e dans toute sa intention was not fully incorporated into the force au texte de Ia Charte,la protection des Charter,with the result that, properly speak- droits et libert~s au Canada n'est pas, Apro- ing, Canada's constitutional bill of rights is prement parler, o enchfiss~e )) dans ]a cons- not "entrenched". The author concludes by titution. En conclusion, l'auteur met 'accent emphasizing the establishment of a "contin- sur l'instauration d'un < colloque continu uing colloquy" involving the courts, the po- auxquels participeraient les tribunaux, les litical institutions, the legal profession and institutions politiques, ]a profession juri- society at large, in the hope that the legiti- dique et le grand public; ]a l6gitimit6 de la macy of the judicial protection of Charter protection judiciaire des droits garantis par rights will turn on the consent of the gov- la Charte serait alors fond6e sur la volont6 erned and the perceived justice of the courts' des constituants et Ia perception populaire de decisions. -

The Canadian Legal Research and Writing Guide Formerly the Best Guide to Canadian Legal Research 2018 Canliidocs 161

The Canadian Legal Research and Writing Guide Formerly the Best Guide to Canadian Legal Research 2018 CanLIIDocs 161 Edited by Melanie Bueckert, André Clair, Maryvon Côté, Yasmin Khan, and Mandy Ostick, based on work by Catherine Best, 2018 The Canadian Legal Research and Writing Guide is based on The Best Guide to Canadian Legal Research, An online legal research guide written and published by Catherine Best, which she started in 1998. The site grew out of Catherine’s experience teaching legal research and writing, and her conviction that a process-based analytical 2018 CanLIIDocs 161 approach was needed. She was also motivated to help researchers learn to effectively use electronic research tools. Catherine Best retired In 2015, and she generously donated the site to CanLII to use as our legal research site going forward. As Best explained: The world of legal research is dramatically different than it was in 1998. However, the site’s emphasis on research process and effective electronic research continues to fill a need. It will be fascinating to see what changes the next 15 years will bring. The text has been updated and expanded for this publication by a national editorial board of legal researchers: Melanie Bueckert legal research counsel with the Manitoba Court of Appeal in Winnipeg. She is the co-founder of the Manitoba Bar Association’s Legal Research Section, has written several legal textbooks, and is also a contributor to Slaw.ca. André Clair was a legal research officer with the Court of Appeal of Newfoundland and Labrador between 2010 and 2013. He is now head of the Legal Services Division of the Supreme Court of Newfoundland and Labrador. -

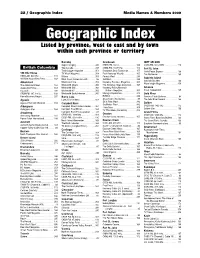

Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by Province, West to East and by Town Within Each Province Or Territory

22 / Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by province, west to east and by town within each province or territory Burnaby Cranbrook fORT nELSON Super Camping . 345 CHDR-FM, 102.9 . 109 CKRX-FM, 102.3 MHz. 113 British Columbia Tow Canada. 349 CHBZ-FM, 104.7mHz. 112 Fort St. John Truck Logger magazine . 351 Cranbrook Daily Townsman. 155 North Peace Express . 168 100 Mile House TV Week Magazine . 354 East Kootenay Weekly . 165 The Northerner . 169 CKBX-AM, 840 kHz . 111 Waters . 358 Forests West. 289 Gabriola Island 100 Mile House Free Press . 169 West Coast Cablevision Ltd.. 86 GolfWest . 293 Gabriola Sounder . 166 WestCoast Line . 359 Kootenay Business Magazine . 305 Abbotsford WaveLength Magazine . 359 The Abbotsford News. 164 Westworld Alberta . 360 The Kootenay News Advertiser. 167 Abbotsford Times . 164 Westworld (BC) . 360 Kootenay Rocky Mountain Gibsons Cascade . 235 Westworld BC . 360 Visitor’s Magazine . 305 Coast Independent . 165 CFSR-FM, 107.1 mHz . 108 Westworld Saskatchewan. 360 Mining & Exploration . 313 Gold River Home Business Report . 297 Burns Lake RVWest . 338 Conuma Cable Systems . 84 Agassiz Lakes District News. 167 Shaw Cable (Cranbrook) . 85 The Gold River Record . 166 Agassiz/Harrison Observer . 164 Ski & Ride West . 342 Golden Campbell River SnoRiders West . 342 Aldergrove Campbell River Courier-Islander . 164 CKGR-AM, 1400 kHz . 112 Transitions . 350 Golden Star . 166 Aldergrove Star. 164 Campbell River Mirror . 164 TV This Week (Cranbrook) . 352 Armstrong Campbell River TV Association . 83 Grand Forks CFWB-AM, 1490 kHz . 109 Creston CKGF-AM, 1340 kHz. 112 Armstrong Advertiser . 164 Creston Valley Advance. -

Mcgill Law Journal Revuede Droitde Mcgill

McGill Revue de Law droit de Journal McGill Vol. 50 DECEMBER 2005 DÉCEMBRE No 4 SPECIAL ISSUE / NUMÉRO SPÉCIAL NAVIGATING THE TRANSSYSTEMIC TRACER LE TRANSSYSTEMIQUE Where Law and Pedagogy Meet in the Transsystemic Contracts Classroom Rosalie Jukier* In this article, the author examines how the Dans cet article, l’auteure examine comment transsystemic McGill Programme, predicated on a fonctionne «sur le terrain», dans un cours d’Obligations uniquely comparative, bilingual, and dialogic contractuelles de première année, le programme theoretical foundation of legal education, operates “on transsystémique de McGill, bâti sur des fondements the ground” in a first-year Contractual Obligations théoriques de l’éducation juridique qui sont à la fois classroom. She describes generally how the McGill comparatifs, bilingues, et dialogiques. Elle explique Programme distinguishes itself from other comparative comment, de manière générale, le programme de or interdisciplinary projects in law, through its focus on McGill se distingue d’autres projets juridiques integration rather than on sequential comparison, as comparatifs ou interdisciplinaires, de par son insistance well as its attempt to link perspectives to mentalités of sur l’intégration plutôt que sur la comparaison different traditions. The author concludes with a more séquentielle, ainsi que de par son objectif de relier les detailed study of the area of specific performance as a perspectives et mentalités propres à différentes particular application of a given legal phenomenon in traditions. L’auteure conclut avec une étude plus different systemic contexts. approfondie de la doctrine de «specific performance» en tant qu’application spécifique dans divers contextes systémiques d'un phénomène juridique donné. * Associate Professor, Faculty of Law, McGill University. -

A Legal and Epidemiological Justification for Federal Authority in Public Health Emergencies

A Legal and Epidemiological Justification for Federal Authority in Public Health Emergencies Amir Attaran & Kumanan Wilson* Federal Canada’s authority to control epidemic Les lois fédérales canadiennes relatives au contrôle disease under existing laws is seriously limited—a reality des maladies épidémiques sont faibles—ce que l’épidémie that was demonstrated in unflattering health and economic du SRAS a démontré tant bien sur le plan de la santé que terms by the SARS epidemic. Yet even Canadians who sur le plan économique. Pourtant, même les canadiens qui work in public health or medicine and who lament the œuvrent dans le domaine de la santé publique ou en federal government’s lack of statutory authority are often médecine et qui lamentent l’impuissance du gouvernement resigned to it because of an ingrained belief that the fédéral s’y résignent souvent. Cela s’explique par la Constitution Act, 1867 assigns responsibility over health to croyance inébranlable que la Loi constitutionnelle de 1867 the provinces and ties Parliament’s hands such that it cède la compétence exclusive en matière de santé aux cannot pass laws for epidemic preparedness and response. provinces, et restreint de surcroît la capacité du Parlement We show in this paper that this belief is legally wrong canadien de mener à bien l’adoption de lois fédérales en and medically undesirable. Not only does Parliament have matière de préparation et de réponse aux épidémies. the constitutional jurisdiction, mainly under the criminal Dans cet article, nous démontrons que cette croyance law and quarantine powers, to pass federal laws for est à la fois erronée sur le plan juridique et indésirable d’un epidemic preparedness and response, but current Supreme point de vue médical. -

Thesis Survey

THESES SURVEY RECENSION DES THESES I. Doctoral Theses/Theses de doctorat Ebow P. Bondzi-Simpson, The International Regulation of Relationships between Transnational Corporations and Host States: Conceptual Analyses and an Inquiry into Attempts at Codification and Control, University of Toronto In this study, a juridical examination is made of the relationships between transnational corporations (TNCs) and host states, especially developing coun- tries as hosts. It notes the positive contributions that TNCs make to host states and encourages this trend. But more especially, it notes the tensions that have existed between them and endeavours to provide legal responses that take into account the legitimate interests of these two main actors. A harmonization approach is adopted in developing the said responses. Some of the specific subjects that have received attention, and for which responses have been provided, include: the scope of the right to renegotiate investment contracts; the conditions for reference of international investment disputes to international dispute settlement machinery; closing loop-holes on transfer pricing practices; providing more certain and uniform consumer and environmental protection standards, and restricting the grounds for nationaliza- tion of foreign property and assessing appropriate compensation therefor. However, while the thesis attempts to develop some juridical responses to regulate some of the inhospitable features of foreign direct investment, it must also be pointed out that the increasingly developing country hosts are seeking to attract foreign investors on reasonable terms. Indeed, many developing coun- tries - as well as former socialist countries - are becoming market-oriented in their policies, either voluntarily or subject to domestic pressures or pressures from international business concerns or even from multilateral agencies such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) or the International Bank for Recon- struction and Development (IBRD). -

Derek Mckee Faculté De Droit, Université De Montréal Pavillon Maximilien-Caron C.P

Derek McKee Faculté de droit, Université de Montréal Pavillon Maximilien-Caron C.P. 6128, succ. Centre-ville Montréal, Québec H3C 3J7 (514) 343-2329 [email protected] I. BACKGROUND Academic and Professional Appointments 2018– Faculté de droit, Université de Montréal Associate Professor 2012–2018 Faculté de droit, Université de Sherbrooke Associate Professor (2018) Assistant Professor (2013–2018) Professor chargé d’enseignement (2012–2013) 2006–2007 Supreme Court of Canada Law Clerk to Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin Education 2007–2013 University of Toronto, Faculty of Law Doctor of Juridical Science (S.J.D.) Dissertation: “Internationalism and Global Governance in Canadian Public Law” Supervisor: Prof. Kerry Rittich SSHRC Canada Graduate Scholarship, 2008–2011 ($105,000) Ontario Graduate Scholarship, 2007–2008 ($15,000) University of Toronto Faculty of Law Doctoral Scholarship, 2007–2008 ($9,000) 2002–2006 McGill University, Faculty of Law Bachelor of Civil Laws/Bachelor of Laws (B.C.L./LL.B.) Dean’s Honour List Joseph Cohen, Q.C. Award, 2006 (shared) Montreal Bar Association Prize for highest standing in Civil Procedure, 2006 Daniel Mettarlin Memorial Scholarship for academic achievement and demonstrated interest in public interest advocacy, 2005 (shared) Harry Batshaw prize for the best result in the course “Foundations of Canadian Law,” 2003 English Editorial Board, McGill Law Journal, 2003–2005 1993–1998 Harvard University Bachelor of Arts magna cum laude Joint concentration in Visual and Environmental Studies and Anthropology Senior thesis: “Darshan in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” PROF. DEREK MCKEE – CURRICULUM VITAE – UPDATED NOVEMBER 2019 1 Professional credentials Law Society of Ontario (called to the bar 2007) Languages English (native speaker), French (fluent), German (intermediate) II. -

Thesis Survey Recension Des Thèses

Thesis Survey Recension des thèses I. Doctoral Theses / Thèses de doctorat Matthew Kingcheong Au, Rights of Private Investors in Global Financial Markets: From Cross- Border Financial Products to Harmonization of Financial Laws in Cyberspace and Post-WTO China, University of British Columbia. Frédéric Bachand, L’intervention du juge canadien avant et durant un arbitrage commercial international, Université de Montréal. Gary Botting, Judicial and Executive Discretion in Extradition Between Canada and the United States, University of British Columbia. Roland Dale Brawn, Paths to the Bench: Judicial Appointments in Manitoba, 1872-1950, Osgoode Hall Law School. Tomer Broude, Judicial Boundedness, Political Capitulation: The Dialectic of International Governance in the World Trade Organization, University of Toronto. Wayne Douglas Burns, Human Rights, Southeast Asia and the Canadian Experience: A Comparative Analysis, University of British Columbia. Julien Cabanac, L’influence de l’esprit scientifique sur la construction des droits français, anglais et québécois au sortir du siècle des lumières, Université d’Ottawa. Harold Cardinal, The Right of Self-Determination for Indian First Nations in Canada, University of British Columbia. Cynthia Chassigneux, L’encadrement juridique des traitements de données personnelles sur les sites de commerce électronique, Université de Montréal. Jia (Jennifer) Chen, International Interdependence in Search of Globalization of Law: Myth or Reality? An Interdisciplinary Perspective, University of British Columbia. Ronald Davis, In Whose Interests? Democracy and Accountability for Pension Fund Corporate Governance Activity, University of Toronto. Innocent Fetze Kamdem, Adaptabilité des instruments juridiques internationaux relatifs au commerce : pour une «convention législative», Université Laval. Joseph Vincent Frankovic, Taxing the Income Generated by Prepayments for Property or Services: A Legal and Time Value of Money Analysis, Osgoode Hall Law School. -

Laws of Desire: the Political Morality of Public Sex

Laws of Desire: The Political Morality of Public Sex Elaine Craig* In indecency cases, Canadian courts historically En matière d’indécence, les cours canadiennes ont employed a model of sexual morality based on the historiquement utilisé un modèle de moralité sexuelle community’s standard of tolerance. However, the se basant sur la norme de tolérance de la société. Supreme Court of Canada’s recent jurisprudence Cependant, la jurisprudence récente de la Cour suprême addressing the role of morality in the criminal law relies du Canada s’appuie sur les valeurs fondamentales upon, in order to protect, the fundamental values garanties par la Constitution canadienne, afin de les enshrined in the Canadian constitution. This article protéger. Cet article analyse les jugements de la Cour analyzes the Court’s decisions in R. v. Labaye and R. v. dans R. c. Labaye et R. c. Kouri et démontre que ces Kouri and demonstrates that these cases represent a affaires représentent une mutation du lien entre le droit shift in the relationship between law and sexuality. The et la sexualité. L’auteure expose la possibilité d’une author illuminates the possibility of a new approach by nouvelle approche de la Cour quant à la régulation des the Court to the regulation of sex. Such an approach relations sexuelles. Une telle approche permettrait la allows for the legal recognition of pleasure behind, reconnaissance judiciaire du plaisir au-delà et hors des beyond, or outside of legal claims regarding identity, revendications touchant l’identité, l’anti-subordination, antisubordination, relationship equality, and l’égalité des relations et le droit à la vie privée. -

A Canadian Political Thinker: Pierre Elliot Trudeau

A CANADIAN POLITICAL THINKER: PIERRE ELLIOT TRUDEAU AN ANALYSIS OF HIS PUBLISHED WRITINGS 1950-1966 by GEORGE LESLIE HAYNAL B.A., Loyola College, 1967 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Political Science We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA -July, 1970 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree tha permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Geotg^ L. Haynal Department of PnHtir.nl Sr.i e.nr.& The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada Date l/ sPrt.PmhPr h 1Q70 ABSTKACT Pierre Elliott Trudeau was an active participant in the decade of social reform and political awakening that preceded the Quiet Revolu• tion in Quebec, and continued to act as a non-partisan social and polit• ical critic until his entry into the federal liberal party in 1966. He based his contribution as pamphleteer for various movements of reform on certain basic philosophical principles. These principles can be described as a belief in the absolute value of humanity, the ef• ficacy of reason in human action, and the necessity of moral participation by the individual in the determination of all phases of his existence. -

THE Mcgill LAW JOURNAL

THE McGILL LAW JOURNAL VOLUME 2 SPRING 1956 NUMBER 2 SECURITY UPON MOVEABLE PROPERTY IN THE PROVINCE OF QUEBEC Gerald E. LeDan* At a time when the economy is experiencing a quite remarkable expansion of credit, it seems appropriate to consider a legal aspect of the subject which must always be a preoccupation of creditors, namely, the kind of security which may be obtained by agreement upon the movable property of a debtor. Most creditors understandably share one weakness, and that is the desire to be secured against the failure or incapacity of their debtor to pay what he owes them at due date. It is the task of law, not merely in the interest of equity and justice, but of commerce itself, to determine which creditors shall enjoy this favour and under what conditions, and what shall be the order of preference among them. The free flow of commerce requires not only that certain persons or institutions be encouraged to extend credit by the guarantee which they are able to obtain of being paid, but that the ordinary unsecured creditor should not be driven from the field by the unreasonable extent to which others have by law or contract been given a preference over him. Among the considerations which must influence the legislator are the types of credit to be encouraged, the protection to be given to the creditor, the debtor and third persons, and the practical necessities of daily life and trade which will determine the kind of collateral offered and the appropriate security device for giving it. -

Book Review(S)

BOOK REVIEWS CANADIAN JURISPRUDENCE Edited by Edward McWhinney University of Toronto Faculty of Comparative Law Series, Volume 4. THE CARSWELL COMPANY LimITED, TORONTO 1958, Pp. xvi, 393. This work is the most recent volume in the Comparative Law Series of the University of Toronto Faculty of Law. Unlike the preceding three volumes, however, it is concerned essentially with a comparative study of law within Canada. Having as its object the "stimulation of legal curiosity, and the promotion of a broader culture in this country of law generally and the two systems within our federalism in particular", this volume constitutes not only a valuable addition to the Series but also a worthwhile asset to any legal library. It attempts to present, for the first time, a survey of the two legal systems within Canada amidst a background of the ethnic-cultural traditions out of which they arose. While the scope of the survey is limited necessarily, by its presentation in one volume, those areas which are covered are done so with a high degree of scholarship and perception. The book is composed of fifteen essays written by prominent legal practi- tioners and professors of law in the common law and civil law jurisdictions of Canada. In addition to presenting essays of a comparative law nature, there are three articles of a more national character. These are a discussion of criminal law in Canada by Robert S. Mackay, a brief outline of procedure and judicial administration in Canada by David Kilgour, and a review of international law and Canadian practice by Maxwell Cohen.