The Limits to Judges' Free Speech: a Comment on the Report of the Committee of Investigation Into the Conduct of the Hon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United States Canada

Comparative Table of the Supreme Courts of the United States and Canada United States Canada Foundations Model State judiciaries vs. independent and Unitary model (single hierarchy) where parallel federal judiciary provinces appoint the lowest court in the province and the federal government appoints judges to all higher courts “The judicial Power of the United “Parliament of Canada may … provide for the States, shall be vested in one Constitution, Maintenance, and Organization of Constitutional supreme Court” Constitution of the a General Court of Appeal for Canada” Authority United States, Art. III, s. 1 Constitution Act, 1867, ss. 101 mandatory: “the judicial Power of optional: “Parliament of Canada may … provide the United States, shall be vested in for … a General Court of Appeal for Canada” (CA Creation and one supreme Court” Art III. s. 1 1867, s. 101; first Supreme Court Act in 1875, Retention of the (inferior courts are discretionary) after debate; not constitutionally entrenched by Supreme Court quasi-constitutional convention constitutionally entrenched Previous higher appeals to the Judicial Committee of the Privy judicial Council were abolished in 1949 authority Enabling Judiciary Act Supreme Court Act, R.S.C. 1985, c. S-26 Legislation “all Cases, in Law and Equity, arising “a General Court of Appeal for Canada” confers under this Constitution” Art III, s. 2 plenary and ultimate authority “the Laws of the United States and Treaties made … under their Authority” Art III, s. 2 “Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls” (orig. jur.) Jurisdiction of Art III, s. 2 Supreme Court “all Cases of admiralty and maritime Jurisdiction” Art III, s. -

The Appointment, Tenure and Removal of Judges Under Commonwealth

The The Appointment, Tenure and Removal of Judges under Commonwealth Principles Appoin An independent, impartial and competent judiciary is essential to the rule tmen of law. This study considers the legal frameworks used to achieve this and examines trends in the 53 member states of the Commonwealth. It asks: t, Te ! who should appoint judges and by what process? nur The Appointment, Tenure ! what should be the duration of judicial tenure and how should judges’ remuneration be determined? e and and Removal of Judges ! what grounds justify the removal of a judge and who should carry out the necessary investigation and inquiries? Re mo under Commonwealth The study notes the increasing use of independent judicial appointment va commissions; the preference for permanent rather than fixed-term judicial l of Principles appointments; the fuller articulation of procedural safeguards necessary Judge to inquiries into judicial misconduct; and many other developments with implications for strengthening the rule of law. s A Compendium and Analysis under These findings form the basis for recommendations on best practice in giving effect to the Commonwealth Latimer House Principles (2003), the leading of Best Practice Commonwealth statement on the responsibilities and interactions of the three Co mmon main branches of government. we This research was commissioned by the Commonwealth Secretariat, and undertaken and alth produced independently by the Bingham Centre for the Rule of Law. The Centre is part of the British Institute of International and -

Mauritius's Constitution of 1968 with Amendments Through 2016

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:39 constituteproject.org Mauritius's Constitution of 1968 with Amendments through 2016 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:39 Table of contents CHAPTER I: THE STATE AND THE CONSTITUTION . 7 1. The State . 7 2. Constitution is supreme law . 7 CHAPTER II: PROTECTION OF FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS OF THE INDIVIDUAL . 7 3. Fundamental rights and freedoms of the individual . 7 4. Protection of right to life . 7 5. Protection of right to personal liberty . 8 6. Protection from slavery and forced labour . 10 7. Protection from inhuman treatment . 11 8. Protection from deprivation of property . 11 9. Protection for privacy of home and other property . 14 10. Provisions to secure protection of law . 15 11. Protection of freedom of conscience . 17 12. Protection of freedom of expression . 17 13. Protection of freedom of assembly and association . 18 14. Protection of freedom to establish schools . 18 15. Protection of freedom of movement . 19 16. Protection from discrimination . 20 17. Enforcement of protective provisions . 21 17A. Payment or retiring allowances to Members . 22 18. Derogations from fundamental rights and freedoms under emergency powers . 22 19. Interpretation and savings . 23 CHAPTER III: CITIZENSHIP . 25 20. Persons who became citizens on 12 March 1968 . 25 21. Persons entitled to be registered as citizens . 25 22. Persons born in Mauritius after 11 March 1968 . 26 23. Persons born outside Mauritius after 11 March 1968 . -

Supreme Court Act 1905

Q UO N T FA R U T A F E BERMUDA SUPREME COURT ACT 1905 1905 : 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS PRELIMINARY 1 Interpretation CONSTITUTION OF THE SUPREME COURT 2 Union of existing Courts into Supreme Court 3 Prescription of number of Puisne Judges 4 Assistant Justices 5 Appointment of Judges of Supreme Court 6 Precedence of Judges 7 Powers of Judges to exercise jurisdiction 8 Powers of Acting Chief Justices 9 Powers etc. of Puisne Judge 10 Seal of Court 11 Place of sitting JURISDICTION AND LAW 12 Jurisdiction of Supreme Court 13 [repealed] 14 Jurisdiction in respect of persons suffering from mental disorder 15 Extent of application of English law 16 [repealed] 17 [repealed] 18 Concurrent administration of law and equity 19 Rules of law upon certain points 20 Proceedings in chambers 21 Provision as to criminal procedure 22 Savings for rules of evidence and law relating to jurors, etc. 1 SUPREME COURT ACT 1905 23 Restriction on institution of vexatious actions ADMIRALTY JURISDICTION 24 Admiralty jurisdiction of the Court 25 Mode of exercise of Admiralty jurisdiction 26 Jurisdiction in personam in collision and other similar cases 27 Wages 28 Supreme Court not to have jurisdiction in cases falling within Rhine Convention 29 Savings DISPOSAL OF MONEY PAID INTO COURT 30 Disposal of money paid into court 31 Payment into Consolidated Fund 32 Money paid into court prior to 1 July 1980 and still in court on that date 33 Notice of payment into court 34 Forfeiture of money 35 Rules relating to the payment of interest on money paid into court SITTINGS AND DISTRIBUTION OF BUSINESS OF THE COURT 36 Sittings of the Court 37 Session day 46 [] OFFICERS OF THE COURT 47 Duties of Provost Marshal General 48 Registrar and Assistant Registrar of the Court 49 Duties of Registrar 50 Taxing Master BARRISTERS AND ATTORNEYS 51 Admission of barristers and attorneys 52 Deposit of certificate of call etc. -

The Judicial Function Under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms Anne F Bayefsky

The Judicial Function under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms Anne F Bayefsky* The author surveys the various American L'auteur resume les differentes theories am6- theories of judicial review in an attempt to ricaines du contr61e judiciaire dans le but de suggest approaches to a Canadian theory of sugg6rer une th6orie canadienne du r8le des the role of the judiciary under the Canadian juges sous Ia Charte canadiennedes droits et Charter of Rights and Freedoms. A detailed libert~s. Notamment, une 6tude d6taille de examination of the legislative histories of sec- 'histoire 1fgislative des articles 1, 52 et 33 de ]a Charte d6montre que les r~dacteurs ont tions 1, 52 and 33 of the Charterreveals that voulu aller au-delA de la Dclarationcana- the drafters intended to move beyond the Ca- dienne des droits et 6liminer le principe de ]a nadianBill ofRights and away from the prin- souverainet6 parlementaire. Cette intention ciple of parliamentary sovereignty. This ne se trouvant pas incorpor6e dans toute sa intention was not fully incorporated into the force au texte de Ia Charte,la protection des Charter,with the result that, properly speak- droits et libert~s au Canada n'est pas, Apro- ing, Canada's constitutional bill of rights is prement parler, o enchfiss~e )) dans ]a cons- not "entrenched". The author concludes by titution. En conclusion, l'auteur met 'accent emphasizing the establishment of a "contin- sur l'instauration d'un < colloque continu uing colloquy" involving the courts, the po- auxquels participeraient les tribunaux, les litical institutions, the legal profession and institutions politiques, ]a profession juri- society at large, in the hope that the legiti- dique et le grand public; ]a l6gitimit6 de la macy of the judicial protection of Charter protection judiciaire des droits garantis par rights will turn on the consent of the gov- la Charte serait alors fond6e sur la volont6 erned and the perceived justice of the courts' des constituants et Ia perception populaire de decisions. -

The Lives of the Chief Justices of England

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com I . i /9& \ H -4 3 V THE LIVES OF THE CHIEF JUSTICES .OF ENGLAND. FROM THE NORMAN CONQUEST TILL THE DEATH OF LORD TENTERDEN. By JOHN LOKD CAMPBELL, LL.D., F.E.S.E., AUTHOR OF 'THE LIVES OF THE LORd CHANCELLORS OF ENGL AMd.' THIRD EDITION. IN FOUE VOLUMES.— Vol. IT;; ; , . : % > LONDON: JOHN MUEEAY, ALBEMAELE STEEET. 1874. The right of Translation is reserved. THE NEW YORK (PUBLIC LIBRARY 150146 A8TOB, LENOX AND TILBEN FOUNDATIONS. 1899. Uniform with the present Worh. LIVES OF THE LOED CHANCELLOKS, AND Keepers of the Great Seal of England, from the Earliest Times till the Reign of George the Fourth. By John Lord Campbell, LL.D. Fourth Edition. 10 vols. Crown 8vo. 6s each. " A work of sterling merit — one of very great labour, of richly diversified interest, and, we are satisfied, of lasting value and estimation. We doubt if there be half-a-dozen living men who could produce a Biographical Series' on such a scale, at all likely to command so much applause from the candid among the learned as well as from the curious of the laity." — Quarterly Beview. LONDON: PRINTED BY WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, STAMFORD STREET AND CHARINg CROSS. CONTENTS OF THE FOURTH VOLUME. CHAPTER XL. CONCLUSION OF THE LIFE OF LOKd MANSFIELd. Lord Mansfield in retirement, 1. His opinion upon the introduction of jury trial in civil cases in Scotland, 3. -

Forum À L'intention Des Juges Spécialisés En Propriété

WIPO/IP/JU/GE/19/INF/1 ORIGINAL: FRANÇAIS / ENGLISH DATE: 13 NOVEMBRE / NOVEMBER 13, 2019 Forum à l’intention des juges spécialisés en propriété intellectuelle Genève, 13 – 15 novembre 2019 Intellectual Property Judges Forum Geneva, November 13 to 15, 2019 LISTE DES PARTICIPANTS LIST OF PARTICIPANTS établie par le Secrétariat prepared by the Secretariat WIPO FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY WIPO/IP/JU/GE/19/INF/1 page 2 I. PARTICIPANTS (par ordre alphabétique / in alphabetical order) ABDALLA Muataz (Mr.), Judge, Intellectual Property Court, Khartoum, Sudan ACKAAH-BOAFO Kweku Tawiah (Mr.), Justice, High Court of Justice, Accra, Ghana AJOKU Patricia (Ms.), Justice, Federal High Court, Ibadan, Nigeria AL BUSAIDI Khalil (Mr.), Judge, Court of First Instance; President, General Administration for Judges, Council of Administrative Affairs for the Judiciary, Muscat, Oman AL KAMALI Mohamed Mahmoud (Mr.), Director General, Institute of Training and Judicial Studies, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates ALABDULQADER Ahmed (Mr.), Appeal Judge, Commercial Court, Dammam, Saudi Arabia ALABUDI Ahmed (Mr.), Appeal Judge, Commercial Section, Appeal Court, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia ALARCON POLANCO Edynson Francisco (Sr.), Magistrado, Corte de Apelación del Distrito Nacional, Santo Domingo, República Dominicana ALEXANDROVA Iskra (Ms.), Judge, Third Department, Supreme Administrative Court, Sofia, Bulgaria ALHIDAR Ibrahim (Mr.), Judge, Commercial Court, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia ALJABRI Nayef (Mr.), Counselor, Court of Appeal, Kuwait City, Kuwait ALKHALAF Mahmoud (Mr.), Judge, Court -

The Canadian Legal Research and Writing Guide Formerly the Best Guide to Canadian Legal Research 2018 Canliidocs 161

The Canadian Legal Research and Writing Guide Formerly the Best Guide to Canadian Legal Research 2018 CanLIIDocs 161 Edited by Melanie Bueckert, André Clair, Maryvon Côté, Yasmin Khan, and Mandy Ostick, based on work by Catherine Best, 2018 The Canadian Legal Research and Writing Guide is based on The Best Guide to Canadian Legal Research, An online legal research guide written and published by Catherine Best, which she started in 1998. The site grew out of Catherine’s experience teaching legal research and writing, and her conviction that a process-based analytical 2018 CanLIIDocs 161 approach was needed. She was also motivated to help researchers learn to effectively use electronic research tools. Catherine Best retired In 2015, and she generously donated the site to CanLII to use as our legal research site going forward. As Best explained: The world of legal research is dramatically different than it was in 1998. However, the site’s emphasis on research process and effective electronic research continues to fill a need. It will be fascinating to see what changes the next 15 years will bring. The text has been updated and expanded for this publication by a national editorial board of legal researchers: Melanie Bueckert legal research counsel with the Manitoba Court of Appeal in Winnipeg. She is the co-founder of the Manitoba Bar Association’s Legal Research Section, has written several legal textbooks, and is also a contributor to Slaw.ca. André Clair was a legal research officer with the Court of Appeal of Newfoundland and Labrador between 2010 and 2013. He is now head of the Legal Services Division of the Supreme Court of Newfoundland and Labrador. -

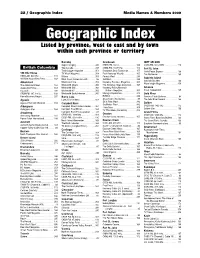

Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by Province, West to East and by Town Within Each Province Or Territory

22 / Geographic Index Media Names & Numbers 2009 Geographic Index Listed by province, west to east and by town within each province or territory Burnaby Cranbrook fORT nELSON Super Camping . 345 CHDR-FM, 102.9 . 109 CKRX-FM, 102.3 MHz. 113 British Columbia Tow Canada. 349 CHBZ-FM, 104.7mHz. 112 Fort St. John Truck Logger magazine . 351 Cranbrook Daily Townsman. 155 North Peace Express . 168 100 Mile House TV Week Magazine . 354 East Kootenay Weekly . 165 The Northerner . 169 CKBX-AM, 840 kHz . 111 Waters . 358 Forests West. 289 Gabriola Island 100 Mile House Free Press . 169 West Coast Cablevision Ltd.. 86 GolfWest . 293 Gabriola Sounder . 166 WestCoast Line . 359 Kootenay Business Magazine . 305 Abbotsford WaveLength Magazine . 359 The Abbotsford News. 164 Westworld Alberta . 360 The Kootenay News Advertiser. 167 Abbotsford Times . 164 Westworld (BC) . 360 Kootenay Rocky Mountain Gibsons Cascade . 235 Westworld BC . 360 Visitor’s Magazine . 305 Coast Independent . 165 CFSR-FM, 107.1 mHz . 108 Westworld Saskatchewan. 360 Mining & Exploration . 313 Gold River Home Business Report . 297 Burns Lake RVWest . 338 Conuma Cable Systems . 84 Agassiz Lakes District News. 167 Shaw Cable (Cranbrook) . 85 The Gold River Record . 166 Agassiz/Harrison Observer . 164 Ski & Ride West . 342 Golden Campbell River SnoRiders West . 342 Aldergrove Campbell River Courier-Islander . 164 CKGR-AM, 1400 kHz . 112 Transitions . 350 Golden Star . 166 Aldergrove Star. 164 Campbell River Mirror . 164 TV This Week (Cranbrook) . 352 Armstrong Campbell River TV Association . 83 Grand Forks CFWB-AM, 1490 kHz . 109 Creston CKGF-AM, 1340 kHz. 112 Armstrong Advertiser . 164 Creston Valley Advance. -

Lord Chief Justice Delegation of Statutory Functions

Delegation of Statutory Functions – Issue No. 2 of 2015 Lord Chief Justice – Delegation of Statutory Functions Introduction The Lord Chief Justice has a number of statutory functions, the exercise of which may be delegated to a nominated judicial office holder (as defined by section 109(4) of the Constitutional Reform Act 2005 (the 2005 Act). This document sets out which judicial office holder has been nominated to exercise specific delegable statutory functions. Section 109(4) of the 2005 Act defines a judicial office holder as either a senior judge or holder of an office listed in schedule 14 to that Act. A senior judge, as defined by s109(5) of the 2005 Act refers to the following: the Master of the Rolls; President of the Queen's Bench Division; President of the Family Division; Chancellor of the High Court; Senior President of Tribunals; Lord or Lady Justice of Appeal; or a puisne judge of the High Court. Only the nominated judicial office holder to whom a function is delegated may exercise it. Exercise of the delegated functions cannot be sub- delegated. The nominated judicial office holder may however seek the advice and support of others in the exercise of the delegated functions. Where delegations are referred to as being delegated prospectively1, the delegation takes effect when the substantive statutory provision enters into force. The schedule, which is Issue 2 of 2015, is correct as at 17 December 2015.2 It contains new delegations, revocation of certain delegations to a number of judges and corrections to the delegations to the President of the Queen’s Bench Division and Chancellor of the High Court. -

Mcgill Law Journal Revuede Droitde Mcgill

McGill Revue de Law droit de Journal McGill Vol. 50 DECEMBER 2005 DÉCEMBRE No 4 SPECIAL ISSUE / NUMÉRO SPÉCIAL NAVIGATING THE TRANSSYSTEMIC TRACER LE TRANSSYSTEMIQUE Where Law and Pedagogy Meet in the Transsystemic Contracts Classroom Rosalie Jukier* In this article, the author examines how the Dans cet article, l’auteure examine comment transsystemic McGill Programme, predicated on a fonctionne «sur le terrain», dans un cours d’Obligations uniquely comparative, bilingual, and dialogic contractuelles de première année, le programme theoretical foundation of legal education, operates “on transsystémique de McGill, bâti sur des fondements the ground” in a first-year Contractual Obligations théoriques de l’éducation juridique qui sont à la fois classroom. She describes generally how the McGill comparatifs, bilingues, et dialogiques. Elle explique Programme distinguishes itself from other comparative comment, de manière générale, le programme de or interdisciplinary projects in law, through its focus on McGill se distingue d’autres projets juridiques integration rather than on sequential comparison, as comparatifs ou interdisciplinaires, de par son insistance well as its attempt to link perspectives to mentalités of sur l’intégration plutôt que sur la comparaison different traditions. The author concludes with a more séquentielle, ainsi que de par son objectif de relier les detailed study of the area of specific performance as a perspectives et mentalités propres à différentes particular application of a given legal phenomenon in traditions. L’auteure conclut avec une étude plus different systemic contexts. approfondie de la doctrine de «specific performance» en tant qu’application spécifique dans divers contextes systémiques d'un phénomène juridique donné. * Associate Professor, Faculty of Law, McGill University. -

Cybercrime Convention Committee (T-CY)

www.coe.int/cybercrime Strasbourg, 30 November 2020 T-CY (2020)33 Cybercrime Convention Committee (T-CY) T-CY 23 23rd Plenary of the T-CY Virtual meeting, 30 November 2020 Meeting report T-CY(2020)33 23rd Plenary/Meeting report 1 Introduction The 23rd Plenary of the T-CY Committee, meeting online on 30 November 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, was chaired by Cristina SCHULMAN (Romania) and opened by Jan KLEIJSSEN (Director of Information Society and Action against Crime, DG 1, Council of Europe). More than 130 representatives of 57 Parties, Observer and Ad-hoc Observer States, as well as of international organisations and Council of Europe committees participated. The regular plenary session was followed by a meeting of the T-CY Protocol Drafting Plenary from 1 to 3 December 2020. 2 Decisions The T-CY decided: Agenda item 1: Opening of the meeting and adoption of the agenda . To adopt the agenda; Agenda item 2: Bureau elections . To thank the outgoing Bureau for its contribution to the work of the T-CY; . To elect Cristina SCHULMAN (Romania) as Chair and Pedro VERDELHO (Portugal) as Vice- chair of the T-CY. To elect as Bureau members: - Albert ANTWI-BOASIAKO (Ghana); - Miriam BAHAMONDE BLANCO (Spain); - Camila BOSCH CARTAGENA (Chile); - Vanessa EL KHOURY-MOAL (France); - Benjamin FITZPATRICK (USA); - Justin MILLAR (United Kingdom); - Gareth SANSOM (Canada); - Nathan WHITEMAN (Australia). Agenda item 3: Terms of Reference for the preparation of the 2nd Additional Protocol . To extend the Terms of reference for the negotiations to May 2021 to permit finalisation of the draft Protocol.