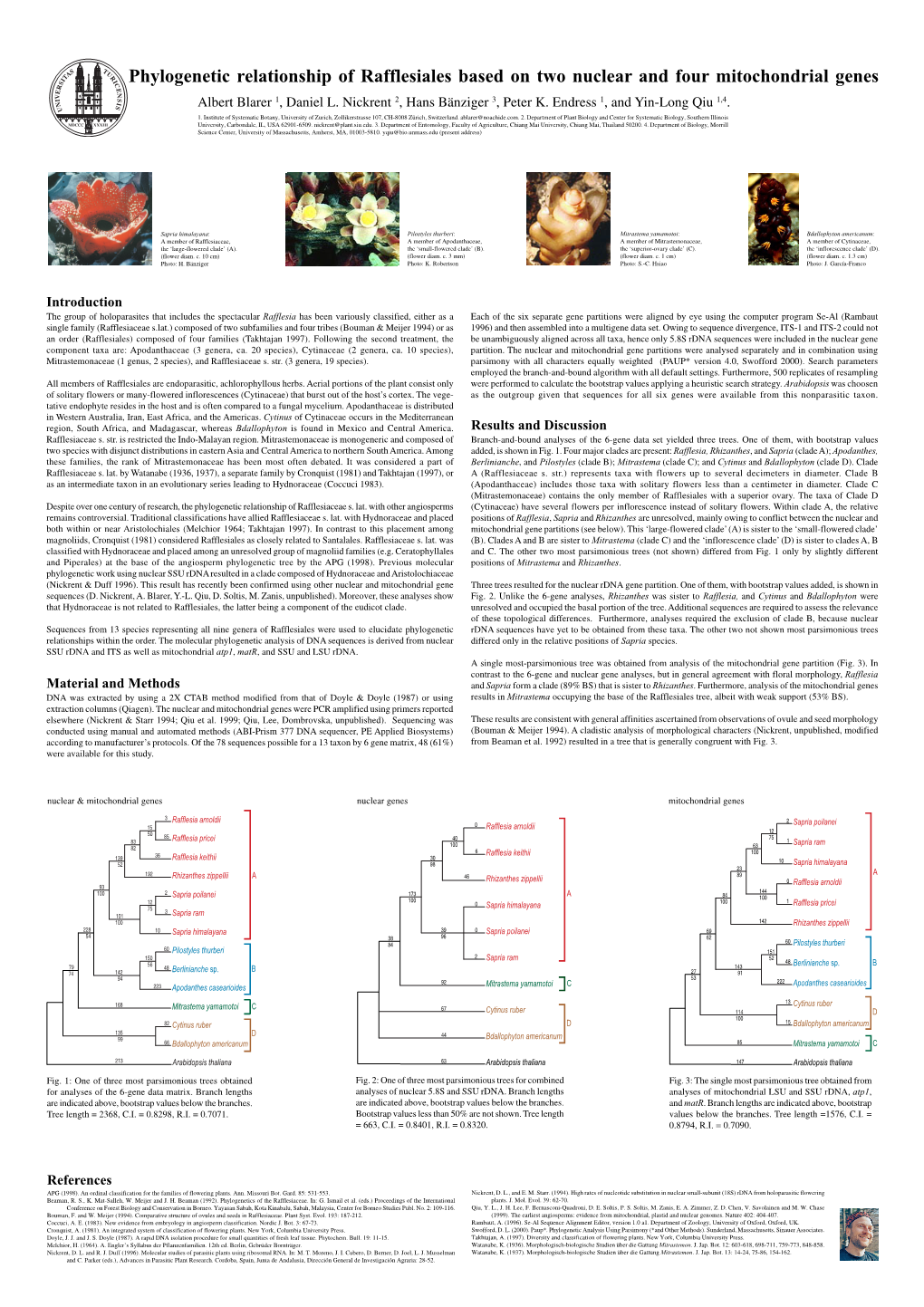

Phylogenetic Relationship of Rafflesiales Based on Two Nuclear and Four Mitochondrial Genes Albert Blarer 1, Daniel L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sapria Himalayana the Indian Cousin of World’S Largest Flower

GENERAL ARTICLE Sapria Himalayana The Indian Cousin of World’s Largest Flower Dipankar Borah and Dipanjan Ghosh Sighting Sapria in the wild is a lifetime experience for a botanist. Because this rare, parasitic flowering plant is one of the lesser known and poorly understood taxa, which is on the brink of extinction. In India, Sapria is only found in the forests of Namdapha National Park in Arunachal Pradesh. In this article, an attempt has been made to document the diversity, distribution, ecology, and conservation need of this valuable plant. Dipankar Borah has just completed his MSc in Botany from Rajiv Gandhi Introduction University, Arunachal Pradesh, and is now pursuing research in the same It was the month of January 2017 when we decided for a field department. He specializes in trip to Namdapha National Park along with some of our plant Plant Taxonomy, though now lover mates of Department of Botany, Rajiv Gandhi University, he focuses on Conservation Arunachal Pradesh. After reaching the National Park, which is Biology, as he feels that taxonomy is nothing without somewhat 113 km away from the nearest town Miao, in Arunachal conservation. Pradesh, the forest officials advised us to trek through the nearest possible spot called Bulbulia, a sulphur spring. After walking for 4 km, we observed some red balls on the ground half covered by litter. Immediately we cleared the litter which unravelled a ball like pinkish-red flower bud. Near to it was a flower in full bloom and two flower buds. Following this, we looked in the 5 m ra- dius area, anticipating a possibility to encounter more but nothing Dipanjan Ghosh teaches Botany at Joteram Vidyapith, was spotted. -

('Mitrastemoneae'). Maki- No's Initial Use in 1909 of This Name (As 'Mitrastemmaeae') Is Invalid As No Descrip- Tion in Either Japanese Or English Was Given (Dr

BLUMEA 38 (1993) 221-229 A revision of Mitrastema (Rafflesiaceae) W. Meijer & J.F. Veldkamp Summary Makino called Mitrastemon has Mitrastema (Rafflesiaceae), usually incorrectly Makino, two spe- cies, one in Southeast Asia and one in Central and South America. Introduction Mitrastema was described by Makino (1909) on M. (‘Mitrastemma’) yamamotoi Makino. He intended to name the genus after the mitre-shaped staminal tube, as becomes evident when in 1911 he changed the name to Mitrastemon.This change is On the other Stearn not allowed and Mitrastemon is a superfluous name. hand, as (1973: 519) has pointed out, the Greek words 'sterna' (thread, stamen) and 'stemma' confused, ‘Mitrastemma’ be (garland or wreath) are easily and so may regarded as an orthographic error to be corrected under Art. 73.1 (Exx. 2, 3). ‘Mitrastemon’ or ‘Mitrastemma’ have been adopted in laterpublications, and even by the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature, where the name Mitrastemonaceae, invalid because it is based on an invalid name contrary to Art. 18.1, is conserved (1988: 104). Since its description Mitrastema yamamotoi has become one of the most widely of the Rafflesiaceae. Watanabe's investigated taxa Especially papers on its morphol- and of devoted it is still ogy biology (1933-1937) are masterpieces study; yet not clear what the precise taxonomic position of the genus is and whether it really be- longs to the Rafflesiaceae. Some authors have regarded it as a distinct family, Mitrastemonaceae Makino (1911) (nom. cons.) (e.g. Cronquist, 1981; 'Mitrastemmataceae', Mabberley, 1987), treatedit Rafflesiaceae tribe others have as Mitrastemateae ('Mitrastemoneae'). Maki- no's initial use in 1909 of this name (as 'Mitrastemmaeae') is invalid as no descrip- tion in either Japanese or English was given (Dr. -

Arthur Monrad Johnson Colletion of Botanical Drawings

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt7489r5rb No online items Arthur Monrad Johnson colletion of botanical drawings 1914-1941 Processed by Pat L. Walter. Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library History and Special Collections Division History and Special Collections Division UCLA 12-077 Center for Health Sciences Box 951798 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1798 Phone: 310/825-6940 Fax: 310/825-0465 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/biomed/his/ ©2008 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Arthur Monrad Johnson colletion 48 1 of botanical drawings 1914-1941 Descriptive Summary Title: Arthur Monrad Johnson colletion of botanical drawings, Date (inclusive): 1914-1941 Collection number: 48 Creator: Johnson, Arthur Monrad 1878-1943 Extent: 3 boxes (2.5 linear feet) Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library History and Special Collections Division Los Angeles, California 90095-1490 Abstract: Approximately 1000 botanical drawings, most in pen and black ink on paper, of the structural parts of angiosperms and some gymnosperms, by Arthur Monrad Johnson. Many of the illustrations have been published in the author's scientific publications, such as his "Taxonomy of the Flowering Plants" and articles on the genus Saxifraga. Dr. Johnson was both a respected botanist and an accomplished artist beyond his botanical subjects. Physical location: Collection stored off-site (Southern Regional Library Facility): Advance notice required for access. Language of Material: Collection materials in English Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Arthur Monrad Johnson colletion of botanical drawings (Manuscript collection 48). Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library History and Special Collections Division, University of California, Los Angeles. -

Museum of Economic Botany, Kew. Specimens Distributed 1901 - 1990

Museum of Economic Botany, Kew. Specimens distributed 1901 - 1990 Page 1 - https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/57407494 15 July 1901 Dr T Johnson FLS, Science and Art Museum, Dublin Two cases containing the following:- Ackd 20.7.01 1. Wood of Chloroxylon swietenia, Godaveri (2 pieces) Paris Exibition 1900 2. Wood of Chloroxylon swietenia, Godaveri (2 pieces) Paris Exibition 1900 3. Wood of Melia indica, Anantapur, Paris Exhibition 1900 4. Wood of Anogeissus acuminata, Ganjam, Paris Exhibition 1900 5. Wood of Xylia dolabriformis, Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 6. Wood of Pterocarpus Marsupium, Kistna, Paris Exhibition 1900 7. Wood of Lagerstremia parviflora, Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 8. Wood of Anogeissus latifolia , Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 9. Wood of Gyrocarpus jacquini, Kistna, Paris Exhibition 1900 10. Wood of Acrocarpus fraxinifolium, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 11. Wood of Ulmus integrifolia, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 12. Wood of Phyllanthus emblica, Assam, Paris Exhibition 1900 13. Wood of Adina cordifolia, Godaveri, Paris Exhibition 1900 14. Wood of Melia indica, Anantapur, Paris Exhibition 1900 15. Wood of Cedrela toona, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 16. Wood of Premna bengalensis, Assam, Paris Exhibition 1900 17. Wood of Artocarpus chaplasha, Assam, Paris Exhibition 1900 18. Wood of Artocarpus integrifolia, Nilgiris, Paris Exhibition 1900 19. Wood of Ulmus wallichiana, N. India, Paris Exhibition 1900 20. Wood of Diospyros kurzii , India, Paris Exhibition 1900 21. Wood of Hardwickia binata, Kistna, Paris Exhibition 1900 22. Flowers of Heterotheca inuloides, Mexico, Paris Exhibition 1900 23. Leaves of Datura Stramonium, Paris Exhibition 1900 24. Plant of Mentha viridis, Paris Exhibition 1900 25. Plant of Monsonia ovata, S. -

HAUSTORIUM 45 August 2004 1 HAUSTORIUM Parasitic Plants Newsletter

HAUSTORIUM 45 August 2004 1 HAUSTORIUM Parasitic Plants Newsletter Official Organ of the International Parasitic Plant Society August 2005 Number 45 IPPS –A MESSAGE FROM THE SECRETARY Science Congress (IWSC), by which the parasitic weed researchers were exposed to the broader scope Dear IPPS Members, of weed science and the IWSC participants could Our most recent Symposium on Parasitic Weeds, take part in presentations and discussions during our which took place in Durban (South Africa) last Symposium. We are grateful to the organizers of the June, was a wonderful occasion to learn about IWSC, and in particular to Baruch Rubin, Vice- progress in many areas of parasitic plant research, to President of the IWSS and member of our Board, discuss new ideas, to meet old friends and for help and encouragement regarding the colleagues, and to make new acquaintances. Let me coordination of these two scientific meetings. take this opportunity to once again thank everyone The International Scientific Committee, with who contributed to the meeting; it was in many representative of the major areas of parasitic plant ways a resounding success! research and control, evaluated all submitted The International Parasitic Plants Society was abstracts, and the final program was constructed inaugurated during the International Parasitic according to their recommendations. We happily Weeds Conference in Nantes. Due to some legal thank all members of the committee for their difficulties it was possible to officially register the contribution to the success of the Symposium. The IPPS as an international society only in 2002. The Proceedings of the 8th International Symposium on Board of Directors provided the Executive Parasitic Weeds can be downloaded from the IPPS Committee with recommendations that are now website at http://www.ppws.vt.edu/IPPS/ . -

1083 a Ground-Breaking Study Published 5 Years Ago Revealed That

American Journal of Botany 100(6): 1083–1094. 2013. SPECIAL INVITED PAPER—EVOLUTION OF PLANT MATING SYSTEMS P OLLINATION AND MATING SYSTEMS OF APODANTHACEAE AND THE DISTRIBUTION OF REPRODUCTIVE TRAITS 1 IN PARASITIC ANGIOSPERMS S IDONIE B ELLOT 2 AND S USANNE S. RENNER 2 Systematic Botany and Mycology, University of Munich (LMU), Menzinger Str. 67 80638 Munich, Germany • Premise of the study: The most recent reviews of the reproductive biology and sexual systems of parasitic angiosperms were published 17 yr ago and reported that dioecy might be associated with parasitism. We use current knowledge on parasitic lineages and their sister groups, and data on the reproductive biology and sexual systems of Apodanthaceae, to readdress the question of possible trends in the reproductive biology of parasitic angiosperms. • Methods: Fieldwork in Zimbabwe and Iran produced data on the pollinators and sexual morph frequencies in two species of Apodanthaceae. Data on pollinators, dispersers, and sexual systems in parasites and their sister groups were compiled from the literature. • Key results: With the possible exception of some Viscaceae, most of the ca. 4500 parasitic angiosperms are animal-pollinated, and ca. 10% of parasites are dioecious, but the gain and loss of dioecy across angiosperms is too poorly known to infer a statisti- cal correlation. The studied Apodanthaceae are dioecious and pollinated by nectar- or pollen-foraging Calliphoridae and other fl ies. • Conclusions: Sister group comparisons so far do not reveal any reproductive traits that evolved (or were lost) concomitant with a parasitic life style, but the lack of wind pollination suggests that this pollen vector may be maladaptive in parasites, perhaps because of host foliage or fl owers borne close to the ground. -

SIGCHI Conference Paper Format

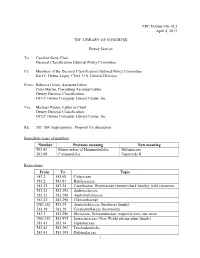

EPC Exhibit 136-19.2 April 4, 2013 THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS Dewey Section To: Caroline Kent, Chair Decimal Classification Editorial Policy Committee Cc: Members of the Decimal Classification Editorial Policy Committee Karl E. Debus-López, Chief, U.S. General Division From: Rebecca Green, Assistant Editor Giles Martin, Consulting Assistant Editor Dewey Decimal Classification OCLC Online Computer Library Center, Inc. Via: Michael Panzer, Editor in Chief Dewey Decimal Classification OCLC Online Computer Library Center, Inc Re: 583–584 Angiosperms: Proposal for discussion Immediate reuse of numbers Number Previous meaning New meaning 583.43 Minor orders of Hamamelididae Dilleniaceae 583.98 Campanulales Euasterids II Relocations From To Topic 583.2 583.68 Cytinaceae 583.2 583.83 Rafflesiaceae 583.22 583.24 Canellaceae, Winteraceae (winter's bark family), wild cinnamon 583.23 583.292 Amborellaceae 583.23 583.296 Austrobaileyaceae 583.23 583.298 Chloranthaceae [583.26] 583.25 Aristolochiaceae (birthwort family) 583.29 583.28 Ceratophyllaceae (hornworts) 583.3 583.296 Illiciaceae, Schisandraceae, magnolia vine, star anise [583.36] 583.975 Sarraceniaceae (New World pitcher plant family) 583.43 583.34 Eupteleaceae 583.43 583.393 Trochodendrales 583.43 583.395 Didymelaceae 1 583.43 583.44 Cercidiphyllaceae (katsura trees) 583.43 583.46 Casuarinaceae (beefwoods), Myricaceae (wax myrtles), bayberries, candleberry, sweet gale (bog myrtle) 583.43 583.73 Barbeyaceae 583.43 583.786 Leitneria 583.43 583.83 Balanopaceae 583.43 583.942 Eucommiaceae 583.44 -

JUDD W.S. Et. Al. (1999) Plant Systematics

CHAPTER8 Phylogenetic Relationships of Angiosperms he angiosperms (or flowering plants) are the dominant group of land Tplants. The monophyly of this group is strongly supported, as dis- cussed in the previous chapter, and these plants are possibly sister (among extant seed plants) to the gnetopsids (Chase et al. 1993; Crane 1985; Donoghue and Doyle 1989; Doyle 1996; Doyle et al. 1994). The angio- sperms have a long fossil record, going back to the upper Jurassic and increasing in abundance as one moves through the Cretaceous (Beck 1973; Sun et al. 1998). The group probably originated during the Jurassic, more than 140 million years ago. Cladistic analyses based on morphology, rRNA, rbcL, and atpB sequences do not support the traditional division of angiosperms into monocots (plants with a single cotyledon, radicle aborting early in growth with the root system adventitious, stems with scattered vascular bundles and usually lacking secondary growth, leaves with parallel venation, flow- ers 3-merous, and pollen grains usually monosulcate) and dicots (plants with two cotyledons, radicle not aborting and giving rise to mature root system, stems with vascular bundles in a ring and often showing sec- ondary growth, leaves with a network of veins forming a pinnate to palmate pattern, flowers 4- or 5-merous, and pollen grains predominantly tricolpate or modifications thereof) (Chase et al. 1993; Doyle 1996; Doyle et al. 1994; Donoghue and Doyle 1989). In all published cladistic analyses the “dicots” form a paraphyletic complex, and features such as two cotyle- dons, a persistent radicle, stems with vascular bundles in a ring, secondary growth, and leaves with net venation are plesiomorphic within angio- sperms; that is, these features evolved earlier in the phylogenetic history of tracheophytes. -

The Fossil Record of Angiosperm Families in Relation to Baraminology

The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism Volume 7 Article 31 2013 The Fossil Record of Angiosperm Families in Relation to Baraminology Roger W. Sanders Bryan College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings DigitalCommons@Cedarville provides a publication platform for fully open access journals, which means that all articles are available on the Internet to all users immediately upon publication. However, the opinions and sentiments expressed by the authors of articles published in our journals do not necessarily indicate the endorsement or reflect the views of DigitalCommons@Cedarville, the Centennial Library, or Cedarville University and its employees. The authors are solely responsible for the content of their work. Please address questions to [email protected]. Browse the contents of this volume of The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism. Recommended Citation Sanders, Roger W. (2013) "The Fossil Record of Angiosperm Families in Relation to Baraminology," The Proceedings of the International Conference on Creationism: Vol. 7 , Article 31. Available at: https://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/icc_proceedings/vol7/iss1/31 Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Creationism. Pittsburgh, PA: Creation Science Fellowship THE FOSSIL RECORD OF ANGIOSPERM FAMILIES IN RELATION TO BARAMINOLOGY Roger W. Sanders, Ph.D., Bryan College #7802, 721 Bryan Drive, Dayton, TN 37321 USA KEYWORDS: Angiosperms, flowering plants, fossils, baramins, Flood, post-Flood continuity criterion, continuous fossil record ABSTRACT To help estimate the number and boundaries of created kinds (i.e., baramins) of flowering plants, the fossil record has been analyzed. To designate the status of baramin, a criterion is applied that tests whether some but not all of a group’s hierarchically immediate subgroups have a fossil record back to the Flood (accepted here as near the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary). -

Evolution of Angiosperm Pollen. 5. Early Diverging Superasteridae

Evolution of Angiosperm Pollen. 5. Early Diverging Superasteridae (Berberidopsidales, Caryophyllales, Cornales, Ericales, and Santalales) Plus Dilleniales Author(s): Ying Yu, Alexandra H. Wortley, Lu Lu, De-Zhu Li, Hong Wang and Stephen Blackmore Source: Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, 103(1):106-161. Published By: Missouri Botanical Garden https://doi.org/10.3417/2017017 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.3417/2017017 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/ page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non- commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. EVOLUTION OF ANGIOSPERM Ying Yu,2 Alexandra H. Wortley,3 Lu Lu,2,4 POLLEN. 5. EARLY DIVERGING De-Zhu Li,2,4* Hong Wang,2,4* and SUPERASTERIDAE Stephen Blackmore3 (BERBERIDOPSIDALES, CARYOPHYLLALES, CORNALES, ERICALES, AND SANTALALES) PLUS DILLENIALES1 ABSTRACT This study, the fifth in a series investigating palynological characters in angiosperms, aims to explore the distribution of states for 19 pollen characters on five early diverging orders of Superasteridae (Berberidopsidales, Caryophyllales, Cornales, Ericales, and Santalales) plus Dilleniales. -

Plant Press, Vol. 22, No. 4

THE PLANT PRESS Department of Botany & the U.S. National Herbarium New Series - Vol. 22 - No. 4 October-November 2019 Parasitic plants: Important components of biodiversity By Marcos A. Caraballo-Ortiz arasitic organisms are generally viewed in a negative way itats. Only a few parasitic plants yield economically impor- because of their ability to “steal” resources. However, tant products such as the sandalwood, obtained from the Pthey are biologically interesting because their depend- tropical shrub Santalum album (order Santalales). Other pro- ency on hosts for survival have influenced their behavior, mor- ducts are local and include traditional medicines, food, and phology, and genomes. Parasites vary in their degree of crafts like “wood roses”. Many parasites are also considered necessity from a host, ranging from being partially independent agricultural pests as they can impact crops and timber plan- (hemiparasitic) to being complete dependent (holoparasitic). tations. Some parasites can live independently, but if they find potential It is difficult to describe a typical parasitic plant because hosts, they can use them to supplement their nutritional needs they possess a wide diversity of growth habits such as trees, (facultative parasitism). terrestrial or aerial shrubs, vines, and herbs. The largest Parasitism is not a phenomenon unique to animals, as there Continued on page 2 are plants parasitic to other plants. Current biodiversity esti- mates indicate that approximately 4,700 species of flowering Tropical mistletoes are very plants are parasitic, which account for about 1.2% of the total inferred number of plant species in the world. About half of the diverse but still poorly known. -

Frontier Lectures in Biology

In the year 2012, INSA initiated a program called “INSA-100 Lectures” to enable INSA Fellows to visit remote instiutions, schools, colleges and Universities and deliver popular lectures that will not only deal with contemporary developments in the field but also inspire the students and teachers who are deprived of exposure to higher institutions of learning. Frontier Lectures In Biology By INSA Fellows Editor S. K. Saidapur FNA Table of Contents Section 1: General Biology ........................................................................................................................... 4 Biology: Its Past, Present & Future ........................................................................................................... 5 S. K. Saidapur ......................................................................................................................................... Discoveries leading to Innovations For Mankind ...................................................................................... 8 V P.Kamboj ............................................................................................................................................ Growth in Childhood and Adolescence .................................................................................................. 19 K. N. Agarwal ........................................................................................................................................ Nature of Science and Biology Education ..............................................................................................