Post-Secular Religion and the Therapeutic Turn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

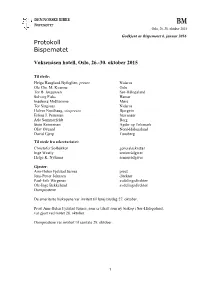

Protokoll Bispemøtet

N ____________________________________________________________________________ Godkjent av Bispemøtet 6. januar 2016 Protokoll Bispemøtet Voksenåsen hotell, Oslo, 26.-30. oktober 2015 Til stede: Helga Haugland Byfuglien, preses Nidaros Ole Chr. M. Kvarme Oslo Tor B. Jørgensen Sør-Hålogaland Solveig Fiske Hamar Ingeborg Midttømme Møre Tor Singsaas Nidaros Halvor Nordhaug, visepreses Bjørgvin Erling J. Pettersen Stavanger Atle Sommerfeldt Borg Stein Reinertsen Agder og Telemark Olav Øygard Nord-Hålogaland David Gjerp Tunsberg Til stede fra sekretariatet: Christofer Solbakken generalsekretær Inge Westly seniorrådgiver Helge K. Nylenna seniorrådgiver Gjester: Ann-Helen Fjelstad Jusnes prost Jens-Petter Johnsen direktør Paul-Erik Wirgenes avdelingsdirektør Ole-Inge Bekkelund avdelingsdirektør Domprostene De emeriterte biskopene var invitert til lunsj tirsdag 27. oktober. Prost Ann-Helen Fjelstad Jusnes, som er tilsatt som ny biskop i Sør-Hålogaland, var gjest ved møtet 28. oktober. Domprostene var invitert til samtale 29. oktober. 1 Protokoll Bispemøtet 26.-30. oktober 2015 Saksliste Saksnr. Sakstittel 31/15 Orienteringssaker 32/15 Kirkeordning 33/15 EVU-saker 34/15 Åndelig veiledning 35/15 Religionsteologi 36/15 Uttalelse: Kirkelig tilsyn i lys av ny kirkeordning 37/15 Sak til Kirkemøtet 2016 38/15 Kontaktmøter 39/15 Erfaringsdeling 40/15 Veien til vigslet tjeneste 41/15 Retningslinjer for kateketens og diakonens gudstjenestelige funksjoner 42/15 Særskilte prekentekster 43/15 Temagudstj enester 44/15 Høringsuttalelser – The Church 45/15 Oppnevninger 2 Protokoll Bispemøtet 26.-30. oktober 2015 BM 31/15 Orienteringssaker 1. Arbeidstid for prester 2. Kirkevalget 2015 3. Fra Fagråd for arbeidsveiledning 4. Revisjon av dåpsliturgien 5. Fra KLK 14. oktober 2015 6. Innføringskurs for nye proster 7. Fra arbeidet i Nådens fellesskap 8. -

Porvoo Prayer Diary 2015

Porvoo Prayer Diary 2015 JANUARY 4/1 Church of England: Diocese of Chichester, Bishop Martin Warner, Bishop Mark Sowerby, Bishop Richard Jackson Evangelical Lutheran Church in Finland: Diocese of Mikkeli, Bishop Seppo Häkkinen 11/1 Church of England: Diocese of London, Bishop Richard Chartres, Bishop Adrian Newman, Bishop Peter Wheatley, Bishop Pete Broadbent, Bishop Paul Williams, Bishop Jonathan Baker Church of Norway: Diocese of Nidaros/ New see and Trondheim, Presiding Bishop Helga Haugland Byfuglien, Bishop Tor Singsaas 18/1 Evangelical Lutheran Church in Finland: Diocese of Oulu, Bishop Samuel Salmi Church of Norway: Diocese of Soer-Hålogaland (Bodoe), Bishop Tor Berger Joergensen Church of England: Diocese of Coventry, Bishop Chris Cocksworth, Bishop John Stroyan. 25/1 Evangelical Lutheran Church in Finland: Diocese of Tampere, Bishop Matti Repo Church of England: Diocese of Manchester, Bishop David Walker, Bishop Chris Edmondson, Bishop Mark Davies Porvoo Prayer Diary 2015 FEBRUARY 1/2 Church of England: Diocese of Birmingham, Bishop David Urquhart, Bishop Andrew Watson Church of Ireland: Diocese of Cork, Cloyne and Ross, Bishop Paul Colton Evangelical Lutheran Church in Denmark: Diocese of Elsinore, Bishop Lise-Lotte Rebel 8/2 Church in Wales: Diocese of Bangor, Bishop Andrew John Church of Ireland: Diocese of Dublin and Glendalough, Archbishop Michael Jackson 15/2 Church of England: Diocese of Worcester, Bishop John Inge, Bishop Graham Usher Church of Norway: Diocese of Hamar, Bishop Solveig Fiske 22/2 Church of Ireland: Diocese -

Oil Discovery Worth Billions

(Periodicals postage paid in Seattle, WA) TIME-DATED MATERIAL — DO NOT DELAY Taste of Norway Leif Erikson Issue Celebrating Happy the love of Det er hyggelig å være viktig, Leif Erikson Day men det er viktigere from the Norwegian fårikål! å være hyggelig. American Weekly! Read more on page 8 – John Cassis Norwegian American Weekly Vol. 122 No. 36 October 7, 2011 Established May 17, 1889 • Formerly Western Viking and Nordisk Tidende $1.50 per copy Norway.com News Find more at www.norway.com Oil discovery worth billions News Latest oil Justice Minister Knut Storber- get acknowledges that mistakes discovery one were made during the terrorist attacks on July 22, and that he of the largest in himself carries the top respon- Norwegian history sibility. In an interview with Aftenposten, Storberget says that he takes responsibility for AF TENP O STEN that which functioned and that which did not function. He says he will never point at anyone The newest oil discovery in else, neither the police nor other the North Sea was upgraded Sept. operational staff. 30 to be one of the five largest oil (blog.norway.com/category/ discoveries in Norwegian history. news) Norwegian newspaper Aftenposten Culture spoke to oil analyst Thina M. Salt- vedt of Nordea Markets about the Nearly all police chiefs in Nor- enormous significance the find will way are against arming Norwe- gian police officers on a regular have for Norwegian oil revenues. basis, according to a survey by Avaldsnes is part of what a Bergens Tidene. Norway is one few weeks ago was described as of very few countries where po- the greatest discovery since the lice still do not regularly carry 1980s, and among the ten largest Photo: Harald Pettersen / Statoil arms. -

Porvoo Prayer Diary 2013

Porvoo Prayer Diary 2013 JANUARY • 6/1 - Chichester (Bishop Martin Warner, Bishop Mark Sowerby, vacancy), Mikkeli (Bishop Seppo Häkkinen) • 13/1 – Ely (Bishop Stephen Conway, Bishop David Thomson), Nidaros/ New see (Bishop Helga Haugland Byfuglien, presiding bishop) • 20/1 - Oulu (Bishop Samuel Salmi), Soer-Hålogaland (Bodoe) (Bishop Tor Berger Joergensen), Coventry (Bishop Chris Cocksworth, Bishop John Stroyan) • 27/1 - Tampere (Bishop Matti Repo), Manchester (Bishop Nigel McCulloch - retiring January 2013, Bishop Chris Edmondson, Bishop Mark Davies) FEBRUARY • 3/2 - Birmingham (Bishop David Urquhart, Bishop Andrew Watson), Cork Cloyne and Ross (Bishop Paul Colton), Elsinore (Bishop Lise-Lotte Rebel) • 10/2 - Bangor (Bishop Andrew John), Dublin and Glendalough (Archbishop Michael Jackson) • 17/2 - Worcester (Bishop John Inge, Bishop David Walker), Hamar (Bishop Solveig Fiske) • 24/2 - Bradford (Bishop Nicholas Baines), Limerick and Killaloe (Bishop Trevor Williams), Roskilde (Bishop Peter Fischer-Moeller) MARCH • 3/3 - Peterborough (Bishop Donald Allister, Bishop John Holbrook), Meath and Kildare (vacancy) • 10/3 – Canterbury (Archbishop Justin Welby, Bishop Trevor Willmott), Down and Dromore (Bishop Harold Miller) • 17/3 - Chelmsford (Bishop Stephen Cottrell, Bishop David Hawkins, Bishop John Wraw, Bishop Christopher Morgan), Karlstad (Bishop Esbjorn Hagberg) • 24/3 - Latvia (Archbishop Janis Vanags, Bishop Einars Alpe, Bishop Pavils Bruvers), Lichfield (Bishop Jonathan Gledhill, Bishop Mark Rylands, Bishop Geoff Annas, Bishop Clive -

Protokoll Bispemøtet

N DEN NORSKE KIRKE BISPEMØTET BM Trondheim, 22.-23. mai 2014 ____________________________________________________________________________ Godkjent av Bispemøtet 15. juni 2014 Protokoll Bispemøtet Trondheim, 22.-23. mai 2014 Til stede: Helga Haugland Byfuglien, preses Nidaros Tor B. Jørgensen, visepreses Sør-Hålogaland Per Oskar Kjølaas Nord-Hålogaland Solveig Fiske Hamar Ingeborg Midttømme Møre Tor Singsaas Nidaros Halvor Nordhaug Bjørgvin Erling J. Pettersen Stavanger Atle Sommerfeldt Borg Stein Reinertsen Agder og Telemark Trond Bakkevig Oslo David Gjerp Tunsberg Til stede fra sekretariatet: Christofer Solbakken Generalsekretær Gjester: Stiftsdirektørene Sak BM 13/14 og 14/14 Saksliste Saksnr. Sakstittel 12/14 Orienteringssaker 13/14 Arbeid med kirkeordning 14/14 Biskopens tilsynstjeneste 15/14 Kirkelig forbønn for likekjønnede ekteskap 16/14 Fremtidig organisering av Det praktisk-teologiske seminar 17/14 Ordning med Olavstipend 18/14 Innføringsprogram for nye proster m.v. 19/14 Studietur til Tyskland 2015 20/14 Manual – vigsling av biskop 21/14 Liturgisaker 22/14 Kurs for ny biskop 1 Protokoll Bispemøtet 22.-23. mai 2014 BM 12/14 Orienteringssaker 1. Høringssak – Undervisningstjenesten i Den norske kirke 2. Besøk av pave Tawadros II 19.-22. juni 2014 3. EVU – kurs for 2015 – statusoppdatering 4. Arbeid med nasjonal høsttakkefest (SF) 5. Prostetjenesten (SF) 6. Brev fra justisministeren – Bispemøtets uttalelse om troskonvertitter 7. Brev til justisministeren – situasjonen for mennesker i kirkeasyl 8. Brev fra Eldar Husøy 9. Glutenfrie nattverdbrød 10. Forholdet til ELCJHL 11. Høring – Kantortjenesten 12. Presteforeningens landskonferanse 13. Høring – Kirkebygg 14. Konferanse om samhandlingsreform BM-12/14 Vedtak: Sakene ble tatt til orientering. BM 13/14 Arbeid med kirkeordning Bispemøtet gjorde i februar 2014 følgende vedtak: BM-03/14 Vedtak: 1. -

Porvoo Prayer Diary 2017

PORVOO PRAYER DIARY 2017 The Porvoo Declaration commits the churches which have signed it ‘to share a common life’ and ‘to pray for and with one another’. An important way of doing this is to pray through the year for the Porvoo churches and their Dioceses. The Prayer Diary is a list of Porvoo Communion Dioceses or churches covering each Sunday of the year, mindful of the many calls upon compilers of intercessions, and the environmental and production costs of printing a more elaborate list. Those using the calendar are invited to choose one day each week on which they will pray for the Porvoo churches. It is hoped that individuals and parishes, cathedrals and religious orders will make use of the Calendar in their own cycle of prayer week by week. In addition to the churches which have approved the Porvoo Declaration, we continue to pray for churches with observer status. Observers attend all the meetings held under the Agreement. The Calendar may be freely copied or emailed for wider circulation. JANUARY 1/1 Church of England: Diocese of Chichester, Bishop Martin Warner, Bishop Mark Sowerby, Bishop Richard Jackson Evangelical Lutheran Church in Finland: Diocese of Mikkeli, Bishop Seppo Häkkinen 8/1 Church of England: Diocese of London, Bishop Richard Chartres, Bishop Adrian Newman, Bishop Graham Tomlin, Bishop Pete Broadbent, Bishop Rob Wickham, Bishop Jonathan Baker, Bishop Ric Thorpe Church of Norway: Diocese of Nidaros/ New see and Trondheim, Presiding Bishop Helga Haugland Byfuglien, Bishop Tor Singsaas 15/1 Evangelical Lutheran Church in Finland: Diocese of Oulu, Bishop Samuel Salmi Church of Norway: Diocese of Soer-Hålogaland (Bodoe), Bishop Ann-Helen Fjeldstad Jusnes Church of England: Diocese of Coventry, Bishop Christopher Cocksworth, Bishop John Stroyan. -

Bispemøtet 2014

BISPEMØTET 2014 Bispemøtet 2011 BispemøtetBispemøtet 20112014 1 BISPEMØTET 2014 Bispemøtet 2014 omslag.indd 1 18-03-15 21:35:41 Innhold Helga Haugland Byfuglien: Verdier i mangfoldsamfunnet 7 Protokoll 10 Bispemøtet 2011 Uttalelse: Om trosfrihet og behandling av troskonvertitter i asylsaker 18 Uttalelse: Urovekkende tvangsutsendelser 43 Årsrapport 45 Vigsling av ny biskop i Tunsberg 57 Helga Haugland Byfuglien: Vigslingstale 58 Per Arne Dahl: Preken 60 Hilsen fra Kirkerådets leder Svein Arne Lindø 64 Hilsen fra bispedømmerådsleder Kjellfred Dekko 65 Vigsling av ny biskop i Nord-Hålogaland 69 Helga Haugland Byfuglien: Vigslingstale 70 Olav Øygard: Preken 72 Hilsen fra Kirkerådets leder Svein Arne Lindø 76 Hilsen fra bispedømmerådsleder Anne Marie Bakken 78 Bispemøtets seminar «Vor kristne og humanistiske Arv» 81 Christofer Solbakken: Åpning av seminaret 82 Program 83 Besøk fra Hans Hellighet Pave Tawadros II 87 Prekener 93 Ole Chr. M. Kvarme: Er Kristus delt? 94 Ingeborg Midttømme: Preken under grunnlovsjubileets bønnedagsgudstjeneste 96 Ole Chr. M. Kvarme: Hos Gud 98 BISPEMØTET 2014 2 3 BISPEMØTET 2014 Bispemøtet 2014 omslag.indd 2 18-03-15 21:35:42 Per Oskar Kjølaas: Preken ved Kirkemøtets åpning 100 Laila Riksaasen Dahl: Preken under Kirkemøtet 104 Solveig Fiske: Påskedagspreken 106 Laila Riksaasen Dahl: Avskjedspreken 108 Stein Reinertsen: Under alle dyp er du Gud! 110 Atle Sommerfeldt: Preken 17. mai 2014 113 Tor Singsaas: Grunnlovsjubileet 1814-2014 116 Helga Haugland Byfuglien: Preken ved økumenisk festgudstjeneste 119 Ingeborg Midttømme: Preken under pilegrimsseilasen fra Stavanger til Trondheim 121 Stein Reinertsen: Gjestfrihet! 124 Atle Sommerfeldt: Preken under nordisk-økumenisk fredsgudstjeneste i Moss 127 Per Oskar Kjølaas: Avskjedspreken 129 Solveig Fiske: Hamar bispedømme 150 år 133 Helga Haugland Byfuglien: Preken ved økumenisk festgudstjeneste 135 Erling J. -

Norwegian Cinnamon Buns Meet Orange and Cardamom in This Fresh Update American Story on Page 14 Volume 127, #21 • July 1, 2016 Est

the Inside this issue: NORWEGIAN Cinnamon buns meet orange and cardamom in this fresh update american story on page 14 Volume 127, #21 • July 1, 2016 Est. May 17, 1889 • Formerly Norwegian American Weekly, Western Viking & Nordisk Tidende $3 USD Norway on the silver screen [What does your world look like? Can you film it?] WHAT’S INSIDE? Mellom Oss: Nyheter / News 2-3 « Filmen er et av de siste Sports 4-5 A portrait of today’s Norway stedene vi kan rømme inn i, der Opinion 6-7 alle drømmer går i oppfyllelse Business 8 MOLLY JONES og alt er magisk. The Norwegian American » Research & Science 9 – Brita Cappelen Møystad Travel 10-11 “What does your world look like? Can you film it?” mally share—their secrets, wishes, processes, important Norway near you 12-13 asks Mellom Oss, Norway’s first documentary film to places or memories, conversations with people special Taste of Norway 14-15 invite all Norwegians to become filmmakers. to them, or simply everyday moments—anything that TV & Film 16-21 Mellom Oss, which translates to “Between Us,” allows them to share their own perspectives with others. will be made entirely of videos submitted by Norwe- To learn more about the intriguing project and the Arts & Entertainment 22 gians. The project started accepting videos in April and inspiration behind it, I was able to get in touch with the Norwegian Heritage 23 as of the beginning of June had received around 400 director, Charlotte Røhder Tvedt, and ask her a few Norsk Språk 24-25 video submissions. -

Protokoll Fra Bispemøtet 2015

BISPEMØTET 2015 Bispemøtet 2011 BispemøtetBispemøtet 20112015 1 BISPEMØTET 2015 Bispemøtet 2015 omslag.indd 1 17-03-16 21:00:36 BISPEMØTET 2015 2 Bispemøtet 2014 omslag.indd 2 18-03-15 21:35:42 Innhold Helga Haugland Byfuglien: Hva skal kirken bry seg om 7 Protokoll 10 Bispemøtet 2011 Uttalelse: Kirkens kall, tall og forpliktelse 21 Uttalelse: Nestekjærlighet og gjestfrihet 28 Olavstipendet 2015 39 Hilde Fylling: Hellige ord i vanlige liv 40 Svend Klemmetsby: Hvorfor de valgte bort dåpen 44 Prekener 49 Erling J. Pettersen: Minnegudstjeneste for trafikkofre 50 Stein Reinertsen: Mer himmel på jord 52 Ole Chr. M. Kvarme: Inn i skyggen, frem i lyset , ut i livet 55 Helga Haugland Byfuglien: Preken på frigjøringsdagen 57 Solveig Fiske: Vigsling av Våler kirke 59 Ingeborg Midttømme: Fra frykt til fred 62 Ingeborg Midttømme: Preken ved førjazzmesse 66 Helga Haugland Byfuglien: Preken ved Olsok 2015 68 Solveig Fiske: Preken under Arendalsuka 71 Tor Singsaas: Vigsling av Stjørdal kirke 73 Atle Sommerfeldt: Preken ved 150-års jubileumsgudstjeneste 76 Atle Sommerfeldt: Preken ved Egil Hovlands Pilegrimsmesse 78 Olav Øygard: Preken ved trosopplæringskonferansen 81 Tor Berger Jørgensen: Avskjedspreken 83 Ole Chr. M. Kvarme: In our darkness – let Your light shine 87 Halvor Nordhaug: Bønn for alle behov? 90 Tor Singsaas: Juledagspreken 92 Stein Reinertsen: To bilder! 95 3 BISPEMØTET 2015 Taler og innlegg 99 Tor Berger Jørgensen: Styrer vi mot et forskjells-Norge? 00 Per Arne Dahl: Toccata – Bachs åndelige univers, og vårt 106 Olav Øygard: Prest i Nord-Hålogaland i ny tid 110 Helga Haugland Byfuglien: Hilsen til Kirkemøtet 2015 113 Per Arne Dahl: Hvem kan redde påsken? 115 Helga Haugland Byfuglien: Assimilering og motstand 117 Solveig Fiske: Mellom kall og tall 119 Atle Sommerfeldt: Etiske perspektiver på integrering av flyktninger 122 Halvor Nordhaug: Protestant og pilegrim? 126 Tor Singsaas: Gratulerer med dagen! 128 Stein Reinertsen: Tre kjennetegn på den gode medarbeider 130 Ole Chr. -

Nytt Norsk Kirkeblad Nr 2-2012

B B NYTT RETURADRESSE Det praktisk-teologiske seminar Postboks 1075 Blindern 0316 Oslo NORSK KIRKE KJøR DeBAtt! BLAD Dette er en oppfordring til Alle om å deltA i NNKs debAttforum slik at det mangfoldige spekteret av tro og meninger blir synlig- gjort. Alle innlegg vil bli redaksjonelt behandlet før en evt. publi- sering. De to neste dødlinjene er 1. april og 11. mai. Max lengde: 8000 anslag. Send til: [email protected] 2. SØNDAG I PÅSKETIDEN ! 17. MAI nn 2 2012 hefte to ÅRGANG føRti ISSN 0800-1642 NYTT 2. søndag i påsketiden NORSK - 17. mai iNNholD NYTT NORSK KIRKE 2-2012 LEDER: ABONNEMENT Hvem tar ballan? ................................................................ 3 KIRKEBLAD Prisendring f.o.m. 01.01. 2011: BLAD Jan Kristian Kjelland Ordinært: kr 250 (student og MAGASINET: Nytt norsk kirkeblad er et folkekirkelig fagblad honnør kr 125) og løper til det Kirken etter Gelius ........................................................... 5 som kommer ut med normalt åtte hefter i året. sies opp skriftlig. Spørsmål kan Trond Blindheim Bladet henvender seg til prester, andre kirkelige sendes på epost til nytt-norsk- Forlengs inn i fremtiden ............................................11 ansatte og lekfolk med interesse for kirke- og [email protected] Brynjulf Jung Lindland-Tjønn gudstjenesteliv. Intervju: Kirkens mennesker i offentligheten ...14 Steinar Ims Nytt norsk kirkeblad viderefører tidsskriftet ANNONSERING Teologi for menigheten og inneholder: Annonser som ønskes rykket inn i bladet sendes som ferdige - Tekster med impulser til kreativ omgang GUDSTJENESTEFORBEREDELSER: pdf- eller jpg-dokumenter til nytt- 2. søndag i påsketiden .....................................................19 med kirkeårets tekster og bevisst gudstjen- [email protected]. Sveinung Hansen estearbeid Annonsepriser: 3. -

Biskop Sven-Bernhards Förbönskalender 2016 Uppdaterad 2 September 2016

1 Biskop Sven-Bernhards förbönskalender 2016 uppdaterad 2 september 2016 Datum Församling på Församling utomlands, med Församling inom Borgågemenskapens Gotland, med de gudstjänstplatser/”satellitförsamlingar” blivande bönekalender socknar/kyrkor knutna till huvudförsamlingen vänstiftet North som ingår i de fall Central Diocese i församlingen Tanzania omfattar mer än en socken. 1-7 januari Dalhem Dubai Monduli Parish Church of England: Diocese 2016 Dalhem, Ganthem of Chichester, Bishop Martin Hörsne, Ekeby Warner, Bishop Mark Sowerby, Bishop Richard Jackson Evangelical Lutheran Church in Finland: Diocese of Mikkeli, Bishop Seppo Häkkinen 8-14 Stånga-Burs Jerusalem Bonde la Ufa Church of England: Diocese januari Parish of London, Bishop Richard Chartres, Bishop Adrian Newman, Bishop Graham Tomlin, Bishop Pete Broadbent, Bishop Rob Wickham, Bishop Jonathan Baker, Bishop Ric Thorpe Church of Norway: Diocese of Nidaros/ New see and Trondheim, Presiding Bishop Helga Haugland Byfuglien, Bishop Tor Singsaas 15-21 Akebäck Frankfurt/Main Malambo Parish Evangelical Lutheran Church januari Kassel, Heidelberg, Saarland, Stuttgart in Finland: Diocese of Oulu, Bishop Samuel Salmi Church of Norway: Diocese of Soer-Hålogaland (Bodoe), Bishop Tor Berger Joergensen Church of England: Diocese of Coventry, Bishop Christopher Cocksworth, Bishop John Stroyan. 22-28 Fröjel Sydney Ngorongoro Evangelical Lutheran Church januari Parish in Finland: Diocese of Tampere, Bishop Matti Repo Church of England: Diocese of Manchester, Bishop David Walker, Bishop Chris Edmondson, -

Årsrapport 2016

Bibelselskapet 2016 ÅRSRAPPORT I 2016 fylte Bibelselskapet 200 år. Ett av mange høydepunkt var bursdagsfest på Jernbanetorget. Soul Children satte stemningen med sitt energifylte show. Bibelselskapet ble stiftet i 1816 og er en økumenisk stiftelse med formål å utbre Bibelen. Bibelarbeidet åpner for dialog og samarbeid nasjonalt og internasjonalt. VÅRE ARBEIDSOMRÅDER ER: Bibeloversettelse – Bibelselskapets oversettelser holder høy kvalitet og støttes av de fleste kirkesamfunn Verbum – Bibelselskapets forlag Bibelgaven – Bibelselskapets internasjonale arbeid Bibel.no – Nettstedet med gratis tilgang til bibelteksten og inspirerende bibelstoff Innhold 2016 INNLEDNING VED GENERALSEKRETÆREN 3 EN ÅPEN BIBEL 5 INTERNASJONALT ARBEID 33 OVERSETTELSESARBEID 43 FORLAGSVIRKSOMHETEN 47 STYRETS ÅRSBERETNING 53 ÅRSREGNSKAP 57 VEDLEGG Vedlegg 1: Gaveinntekter 71 Vedlegg 2: Bevilgninger 71 Vedlegg 3: Bibelsalg 74 Vedlegg 4: Styrende organer, utvalg og ansatte 74 INNLEDNING VED GENERALSEKRETÆREN Feståret 2016! Vi har lagt bak oss et festår! 200-års- vestens kapitalisme. I Ukraina har jubileet ble feiret i hele landet. I Oslo bibelselskapet engasjert seg for og Kristiansand sto Bibelselskapet internt fordrevne flyktninger, for selv som arrangør av bibelfestivaler soldater på begge sider av fronten. Og som til sammen nådde om lag 20 000 ikke minst er bibelselskapet en sentral mennesker. I resten av landet har aktør i landets religiøse råd som har det vært en mengde lokale feiringer jevnlige møter både med regjerings- gjennom hele året. Jubileumsåret har medlemmer og parlamentarikere. På INGEBORG MONGSTAD-KVAMMEN gitt Bibelen en synlighet i samfunnet Balkan har bibelselskapene i Serbia, GENERALSEKRETÆR langt utover et normalår. Jubileet har Slovenia, Makedonia, Albania og Kro- også være meget viktig for Bibelsel- atia et utstrakt samarbeid. I en region skapets synlighet og omdømme.