In the City of Victoria, Vancouver Island Hosts the Oldest, and At

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

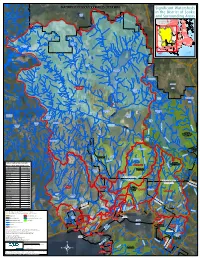

Significant Watersheds in the District of Sooke and Surrounding Areas

Shawnigan Lake C O W I C H A N V A L L E Y R E G I O N A L D I S T R I C T Significant Watersheds in the District of Sooke Grant Lake and Surrounding Areas North C o w i c h a n V a l l e y Saanich R e g i o n a l D i s t r i c t Sidney OCelniptrahl ant Lake Saanich JdFEA H a r o S t r a Highlands it Saanich View Royal Juan de Fuca Langford Electoral Area Oak Bay Esquimalt Jarvis Colwood Victoria Lake Sooke Weeks Lake Metchosin Juan de Fuca Electoral Area ca SpectaFcu le Lake e d it an ra STUDY Ju St AREA Morton Lake Sooke Lake Butchart Lake Devereux Sooke River Lake (Upper) Council Lake Lubbe Wrigglesworth Lake Lake MacDonald Goldstream Lake r Lake e iv R e k o Bear Creek o S Old Wolf Reservoir Boulder Lake Lake Mavis y w Lake H a G d Ranger Butler Lake o a l n d a s Lake Kapoor Regional N C t - r i a s Forslund Park Reserve e g n W a a a o m r l f C r a T Lake r e R e k C i v r W e e e r a k u g h C r e Mount Finlayson e k Sooke Hills Provincial Park Wilderness Regional Park Reserve G o ld s Jack t re a Lake m Tugwell Lake R iv e r W augh Creek Crabapple Lake Goldstream Provincial Park eek Cr S ugh o Wa o Peden k Sooke Potholes e Lake C R Regional Park h i v a e Sheilds Lake r r t e r k e s re C ne i R ary V k M e i v e r e r V C Sooke Hills Table of Significant Watersheds in the e d i t d c Wilderness Regional h o T Charters River C Park Reserve District of Sooke and Surrounding Areas r e e k Watershed Name Area (ha) Sooke Mountain Sooke River (Upper) 27114.93 Boneyard Provincial Park Lake DeMamiel Creek 3985.29 Veitch Creek 2620.78 -

Greater Victoria Police Integrated Units

GREATER VICTORIA POLICE INTEGRATED UNITS ANNUAL REPORT 2017/18 Review :: 2017/18 A MESSAGE FROM THE GREATER VICTORIA POLICE CHIEFS AND DETACHMENT COMMANDERS he Greater Victoria Police Chiefs and Detachment Commanders are pleased to present the second annual Greater Victoria TPolice Integrated Units Annual Report for 2017/2018. This report highlights the work on the many integrated policing units working within Greater Victoria area communities. Common among all of the integrated policing units is a shared desire to work with communities to deliver high-quality, well-coordinated, and cost effective police services. The area Police Chiefs and Detachment Commanders, in consultation with community leaders, remain committed to the identification and implementation of further integration options in situations where improvements in service delivery and financial efficiencies are likely to be realized. Please take a few moments to read the report which highlights the mandate and ongoing work of each integrated policing unit. We wish to thank the dedicated officers working within the integrated policing units for their professionalism and continued commitment to our communities. Proudly, The Greater Victoria Police Chiefs and Detachment Commanders: » Chief Del Manak – Victoria Police » Inspector Todd Preston – Westshore Detachment » Chief Bob Downie – Saanich Police » S/Sgt Wayne Conley – Sidney/North Saanich Detachment » Chief Les Sylven – Central Saanich Police » S/Sgt Jeff McArthur – Sooke Detachment » Chief Andy Brinton – Oak Bay Police Table -

Aquifers of the Capital Regional District

Aquifers of the Capital Regional District by Sylvia Kenny University of Victoria, School of Earth & Ocean Sciences Co-op British Columbia Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection Prepared for the Capital Regional District, Victoria, B.C. December 2004 Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data Kenny, Sylvia. Aquifers of the Capital Regional District. Cover title. Also available on the Internet. Includes bibliographical references: p. ISBN 0-7726-52651 1. Aquifers - British Columbia - Capital. 2. Groundwater - British Columbia - Capital. I. British Columbia. Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection. II. University of Victoria (B.C.). School of Earth and Ocean Sciences. III. Capital (B.C.) IV. Title. TD227.B7K46 2004 333.91’04’0971128 C2004-960175-X Executive summary This project focussed on the delineation and classification of developed aquifers within the Capital Regional District of British Columbia (CRD). The goal was to identify and map water-bearing unconsolidated and bedrock aquifers in the region, and to classify the mapped aquifers according to the methodology outlined in the B.C. Aquifer Classification System (Kreye and Wei, 1994). The project began in summer 2003 with the mapping and classification of aquifers in Sooke, and on the Saanich Peninsula. Aquifers in the remaining portion of the CRD including Victoria, Oak Bay, Esquimalt, View Royal, District of Highlands, the Western Communities, Metchosin and Port Renfrew were mapped and classified in summer 2004. The presence of unconsolidated deposits within the CRD is attributed to glacial activity within the region over the last 20,000 years. Glacial and glaciofluvial modification of the landscape has resulted in the presence of significant water bearing deposits, formed from the sands and gravels of Capilano Sediments, Quadra and Cowichan Head Formations. -

Greater Victoria & Region Greater Victoria & Region

Galiano Island Greater Greater Mayne Victoria Island Salt Spring Island Saturna North Island & Region S Pender & Region D N A Island L S For more detailed I F L U 5 59 G maps, see pages 8– . D N A R South E V U Pender O C The Gulf Islands N Island A V O T Saanich Peninsula & Sidney Victoria, Saanich, Esquimalt & Oak Bay S A BC Ferries – WestShore, Colwood, Langford, Highlands, 1 NORTH Swartz Bay View Royal & Metchosin A SAANICH Ferry Terminal N I Sooke & Port Renfrew Mill C Bay H I TO SA N JUAN I N 2 SLA ND AND SIDNEY ANA T COR L Victoria TES LEGEND: R A Gulf Islands N E International S National Park - Airport C T Highway A Reserve N A D A Main Road UNITED STATES H W Y John Dean 17 Ferry Route . Provincial Sidney CANADA Park James Island Park Island CENTRAL Ferry Terminal Brentwood SAANICH Bay Island View Victoria Int’l Airport Beach Park P Full-Service Seaplane A M T R B Terminal A A S Y T N H W Helijet Terminal O R Y S Gowlland Tod . Y Provincial A A Mount Work I L Park Sooke T N Regional Elk I Lake F Park Lake 17A O 1 F HIGHLANDS Cordova Bay Beaver Elk/Beaver G Lake Lake E Regional O VIEW Park R ROYAL G N I Francis Mt. Douglas A King Park Regional Goldstream Thetis Lake Park SAANICH Provincial Regional Park Park University r 17 of Victoria e v i R Sooke Mount W E Potholes 1A WESTSHORE Tolmie Provincial Park Cadboro-Gyro Park LANGFORD Royal Roads VICTORIA Park . -

AGENDA GREATER VICTORIA PUBLIC LIBRARY BOARD Central Library, 735 Broughton Street Community Meeting Room November 28, 2017 at 12:00 P.M

AGENDA GREATER VICTORIA PUBLIC LIBRARY BOARD Central Library, 735 Broughton Street Community Meeting Room November 28, 2017 at 12:00 p.m. The GVPL Board recognizes and acknowledges the traditional territory of the Esquimalt and Songhees Nations on which the Central Branch is located and Board Meetings take place. 1. APPROVAL OF AGENDA Motion to Approve 2. CHAIR’S REMARKS For Information 3. APPROVAL OF MINUTES 3.1 Minutes of the Board Meeting of October 24, 2017 Attachment #3.1 Motion to Approve 4. BUSINESS ARISING FROM PREVIOUS MEETING None 5. CEO REPORT TO THE BOARD Attachment #5 For Information 6. COMMITTEE REPORTS 6.1 Planning and Policy Committee Meeting November 7, 2017 Oral Report For Information 6.1.1 Planning and Policy Committee Meeting Minutes June 20, 2017 Attachment #6.1.1 Motion to Approve 6.1.2 Policy #G.3 Board Roles and Structure Attachment #6.1.2 Motion to Approve 6.1.3 Trustee Mentorship Proposal Attachment #6.1.3 Motion to Approve 7. FINANCIAL STATEMENT 7.1 Statement of Financial Activity ending October 31, 2017 Attachment #7.1 Motion to Approve 8. NEW BUSINESS 8.1 2018 Proposed Board Meeting dates Attachment #8.1 Motion to Approve 9. REPORTS / PRESENTATIONS (COMMUNITY & STAFF) 9.1 Staff Presentations For Information • Staff Day 2017/2018 Presentation Attachment # 9.1 Motion to Approve • Truth & Reconciliation Commission Recommendations & GVPL support For Information 9.2 BCLTA Update For Information 9.3 Friends of the Library Update For Information 9.4 IslandLink Federation Update For Information 10. BOARD CORRESPONDENCE 10.1 Letter - Ministry of Education, Libraries Branch Public Library Grants Attachment #10.1 Motion to Receive 10.2 Letter – Name that Library, City of Victoria Attachment #10.2 10.3 Letter – City of Colwood, 2018 Board Appointment Attachment #10.3 12. -

N Quaternary Geological Map of Greater Victoria

R2R2 C1C1 R1/2R1/2 C2C2 C1C1 R1/2R1/2 53780005378000 C1C1 TT This map and accompanying information are not intended to be used for site T/C3T/C3 C2C2 C2C2 TT R2R2 specific evaluation of properties. Soil and ground conditions in the map area R1/2R1/2 TT R2R2 C2C2 C1C1 C2C2 DurranceDurrance RdRd were interpreted based on borehole data and other information, available prior to C1C1 DurranceDurrance RdRd Geological Survey Branch R2R2TT R2R2 the date of publication and obtained from a variety of sources. Conditions and TaTa HighwayHighwayHighway 17 17 17 C1C1 HighwayHighwayHighway 17 17 17 C1C1 R1/2R1/2 R1/2R1/2 HighwayHighwayHighway 17 17 17 R1/2R1/2 C3C3 R2R2 N Geoscience Map 2000-2, interpretations are subject to change with time as the quantity and quality of C3C3 C1C1 O1O1 available data improves. The authors and the Ministry of Energy and Mines are R2aR2a TaTa R2R2 TT TaTa O2O2 TT R2R2 R1/2R1/2 R1/2R1/2 not liable for any claims or actions arising from the use or interpretation of this ✚ ✚ R1/2R1/2 R2R2C1C1 ✚ data and do not warrant its accuracy and reliability. R2R2 R1/2R1/2C1C1 R1/2R1/2 TT R1/2R1/2 C1C1 R2R2 ✚ C1C1 T/C3T/C3 53770005377000 C1C1 O2O2 R2R2 ✚ C2C2 T/C3T/C3 O1O1 QUATERNARY GEOLOGICAL MAP OF GREATER VICTORIA O1O1 WallaceWallace DrDr R1R1 ✚ R2aR2a R2R2 O2O2 R2R2 R2aR2a O2O2 R2R2 C1C1 R2R2 R2R2 R1/2R1/2 R1/2R1/2 R2R2 C1C1 TRIM SHEETS (92B.043, 044, 053 & 054) C2C2 ✚ O2O2 C2C2 R2R2 ✚ ✚ O1O1 ✚ R1/2R1/2 O1O1 R2R2 R1/2R1/2 O2O2 R2R2 O2O2 R1/2R1/2 ✚ 1 2 O2O2 ✚ Patrick A. -

NEWS RELEASE June 28 2016

NEWS RELEASE June 28 2016 BEACON COMMUNITY SERVICES ELECTS BOARD; HONOURS STUDENT VOLUNTEERS SIDNEY, BC – Beacon Community Services’ members today elected five new Board members to help govern and guide the successful local charity. Beacon also gave scholarships to five graduating high school students for exemplary volunteerism and community service. “Our new directors are leaders in their fields, clearly dedicated to excellence,” said Board Chair Chuck Rowe. “They also share Beacon’s commitment to helping people and improving lives, and we look forward to working with them.” The new directors are: Saanich resident/professor Dr. Rebecca Grant; Victoria HR professional Denise Lloyd; Esquimalt resident/executive coach Carla Robinson; North Saanich resident/retired risk manager Graham Sanderson, and Saanich resident/businessperson Andy Spurling. Elected at Beacon’s 42nd Annual General Meeting, they join seven community members already on Beacon’s Board: Chuck Rowe, Joan Axford, Jim Brookes, Dr. Howard Brunt, Penny Donaldson, Geri Hinton, and Bryan Waller. $1500 Beacon Community Services Scholarships were presented to: Zachary Coey (Reynolds Secondary) for community service including promoting children’s love of nature; Solomon Lindsay (Victoria High) for his community advocacy (including with the Victoria Microhousing Project); Amanda Punch (Stellys Secondary) for humanitarian and environmental service (including working with the Habitat Acquisition Trust to restore Oak Haven Park); and Junessa Sladen-Dew (Gulf Island Secondary) for service that includes helping feed families in need on Saltspring Island. A $500 Donna Godwin Humanitarian Award went to Parkland Secondary’s Alexandria Fleming for contributions to her school, Beacon’s Youth Employment Program and the Canadian Federation of University Women. -

Greater Victoria

A VILLAGE OF Things to celebrate QUALITY OF LIFE IN WHAT + things to improve GREATER WOULD IT LOOK 10 0 LIKE? SURVEY SAYS... VICTORIA Sarah Black, Athletic Therapist at Athletic Therapy Plus, working with paralympian Jackie Gay at the Athletic Centre. SPECIAL FEATURE BELONGING OR BARRIERS? How our institutions, public policies, social structures, and systems set the tone SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS Canada signs on to achieving these goals at home and abroad VITAL WHAT IS ® COMMUNITY GREGG ELIGH VITAL SIGNS ? NETWORK Measuring well-being, creating change Earlier this year, the Victoria’s Vital Signs® is an following community annual community check-up experts joined us to help that measures the vitality of guide Vital Signs® and its our region, identifies concerns, engagement throughout and supports action on issues the region. We thank them that are critical to our quality for their support. of life. The Victoria Foundation Marika Albert, Community produces the report to connect Social Planning Council philanthropy to community Andrea Carey, Sport needs and opportunities. This for Life The Victoria Foundation’s Sandra Richardson, Chief Executive Officer, and is the 12th consecutive year Jill Doucette, Synergy Patrick Kelly, Chair, Board of Directors the report has been published. Enterprises As part of our commitment to Colleen Hobson, Saanich ABOUT THE continual advancement, we Neighbourhood Place sought community feedback to Society VICTORIA FOUNDATION Vital Signs® that helped us to Catherine Holt, Greater Our vision: A vibrant, caring community for all make improvements this year Victoria Chamber of and beyond. Commerce Established in 1936, the Victoria Foundation is Canada’s second Special thanks to the oldest community foundation and the sixth largest of nearly Fran Hunt-Jinnouchi, Toronto Foundation for Aboriginal Coalition to End 200 nation-wide. -

Ucluelet Final

Culture and Heritage Study, Marine Resource Sites and Activities, Maa-nulth First Nations Uchucklesaht Tribe Project Final Report Illustration of “Ouchucklesit Village” by Frederick Whymper, 1864. Beinecke Library, Yale. Prepared for Uchucklesaht Tribe by Traditions Consulting Services, Inc. Chatwin Engineering Ltd. March 12, 2004 “But the ocean is more the home of these people than the land, and the bounteous gifts of nature in the former element seem more to their taste and are more easily procured than the beasts of the forest.... ...Without a question these people are the richest in every respect in British Columbia...” George Blenkinsop, 1874. Note to Reader Thanks is offered to the Maanulth First Nations for their support of the project for which this is the Final Report, and especially to the h=aw`iih (chiefs), elders and cultural advisors who have shared their knowledge in the past, and throughout the project. In this report, reference is made to “Maanulth First Nations,” a recent term. Within the context of this report, that term is intended to refer to the Huuayaht First Nation, the Uchucklesaht Tribe, the Toquaht First Nation, the Ucluelet First Nation, the Ka:'yu:k't'h/Che:k'tles7et'h' First Nation, and to the tribes and groups that were their predecessors. No attempt has been made to standardize the linguistic transcription of native names or words in this report. These are presented in the manner in which they were encountered in various source materials. Management Summary This is the Final Report for the Culture and Heritage Study, Marine Resource Sites and Activities, Maanulth First Nations. -

2019 Annual Report

Greater Victoria Drinking Water Quality 2019 Annual Report Parks & Environmental Services Department Environmental Protection Prepared By Water Quality Program Capital Regional District 479 Island Highway, Victoria, BC, V9B 1H7 T: 250.474.9680 F: 250.474.9691 www.crd.bc.ca May 2020 Greater Victoria Drinking Water Quality 2019 Annual Report EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report provides the annual overview of Capital Regional District (CRD) Water Quality Monitoring program and its results on water quality in 2019 within the Greater Victoria Drinking Water System (GVDWS) and its individual system components (Map 1). The results indicate that Greater Victoria’s drinking water continues to be of good quality and is safe to drink. The monitoring program is designed to meet the requirements of the provincial regulatory framework, which is defined by the BC Drinking Water Protection Act and Drinking Water Protection Regulation, and follow the federal guidelines for drinking water quality. The approximately 11,000 hectares of the Sooke and Goldstream watersheds comprise the source of our regional drinking water supply area. Water flows from the reservoirs to the Sooke and Goldstream (formerly called Japan Gulch) water treatment plants and then through large-diameter transmission mains and a number of storage reservoirs into eight different distribution systems, which in turn deliver the drinking water to the consumers. The monitoring program covers the entire system to anticipate any issues (i.e., source water monitoring), ensure treatment is effective (i.e., monitoring at the treatment facilities), and confirm a safe conveyance of the treated water to customers (i.e., transmission and distribution system monitoring). -

2021 03 16 Council Agenda

TOWN OF VIEW ROYAL COUNCIL MEETING TUESDAY, MARCH 16, 2021 @ 7:00 PM VIEW ROYAL MUNICIPAL OFFICE - COUNCIL CHAMBERS AGENDA Please note, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Town Hall has limited access at this time and for the protection of the community, Council and staff, this meeting will be held without the public present under the Province's Ministerial Order No. M192. This meeting will be live webcast commencing at 7:00 p.m. and may be viewed by clicking on the following link: Click here to view the live webcast If you would like to participate in the meeting by phone or via the chat feature, please see information below: Phone: 778-402-9227 and use Conference ID: 472 488 489# Chat Feature: The chat feature is available through the "Click here to view the live webcast" link above and by looking for the Q&A icon at the top right hand corner of the screen during the live webcast. You may also provide your written comments to the Town via email to [email protected] or drop them off at the Town Hall or put them in the Town's mail drop box (located to the left of the main doors at Town Hall, 45 View Royal Avenue), up until 3:00 p.m. on Tuesday, March 16, 2021 for inclusion in the March 16, 2021 agenda. If you have any questions, please contact the Administration Department at 250-479- 6800. 1. CALL TO ORDER (Mayor Screech) 2. APPROVAL OF AGENDA (motion to approve) 3. MINUTES, RECEIPT & ADOPTION OF (motion to adopt) a) Minutes of the Council meeting held March 2, 2021 Pg.5 - 8 4. -

List of Early House Names in Greater Victoria

List of Early House Names in Greater Victoria House name Address Owner Municipality Aberdeen Yates Street Gordon, J.A. (Mrs) Victoria Aberdeen 912 Blanshard Street Gordon, Louise E. Victoria Aberdovey 516 Michigan Street Victoria Abergeldie Stanley Street cor Rithet Esquimalt Aberlour 1397 Richardson Street Patterson, J. Victoria Aberthaw 1007 Linden Avenue Williams, William T. Victoria Aboyne 406 Vancouver Street Matthews, John Victoria Acadia 338 Niagara Street Tripp, Alfred Victoria Ackhurst 2177 Lafayette Road Acorn, The 2085 Chaucer Street Bird, A.J. Victoria Adare Lodge 1733 Fairfield Road Bayliss, William Victoria Aidenn 14 Pakington Street Gardiner, George Victoria Alberta Lodge 1610 Belcher Avenue Shaw, John Victoria Albeth 1145 Fairfield Road Victoria Alcombe Wilmot Place Ard, Wm C. Oak Bay Alesia Lampson Street near Lyall Cherry, John W. Esquimalt Street Algoa 1629 Rockland Avenue Holland, Cuyler A. Victoria Allandale 818 Hillside Avenue [56] Grahame, James A. (Mrs) / Victoria Grahame, Henry M. Aloha 2631 Douglas Street Tye, A. Louise Victoria Alpha Lodge 408 Alpha Street Smith, William H. Victoria Altadena 1514 Elford Street Howell, George C. Victoria Alvin 1007 Johnson Street Bossi, Giacomo Victoria Alwyn 2620 Government Street Babington, Panmore A. Victoria Alwyn 1135 McClure Babington, A. Panmure Victoria Am Meer 4 Boyd Street Smith, Garett Victoria Anchor Cottage Powderley Avenue Emery, A.S. Victoria Anchorage Niagara Street at Rendall Goddard, S.M. Victoria Street Anchorage, The 80 Dallas Road Victoria Angela 923 Burdett Avenue Rant, Norman W.F. Victoria Annandale 1675 York Place Tupper, Charles H. / Scott, R. Oak Bay Arbutus 1471 Fairfield Road Crawford, F.L. Victoria Arbutus Lodge 638 Elliot Street Helmcken, John S.