On the Core Elements of the Experience of Playing Video Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Anime Galaxy Japanese Animation As New Media

i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i i Herlander Elias The Anime Galaxy Japanese Animation As New Media LabCom Books 2012 i i i i i i i i Livros LabCom www.livroslabcom.ubi.pt Série: Estudos em Comunicação Direcção: António Fidalgo Design da Capa: Herlander Elias Paginação: Filomena Matos Covilhã, UBI, LabCom, Livros LabCom 2012 ISBN: 978-989-654-090-6 Título: The Anime Galaxy Autor: Herlander Elias Ano: 2012 i i i i i i i i Índice ABSTRACT & KEYWORDS3 INTRODUCTION5 Objectives............................... 15 Research Methodologies....................... 17 Materials............................... 18 Most Relevant Artworks....................... 19 Research Hypothesis......................... 26 Expected Results........................... 26 Theoretical Background........................ 27 Authors and Concepts...................... 27 Topics.............................. 39 Common Approaches...................... 41 1 FROM LITERARY TO CINEMATIC 45 1.1 MANGA COMICS....................... 52 1.1.1 Origin.......................... 52 1.1.2 Visual Style....................... 57 1.1.3 The Manga Reader................... 61 1.2 ANIME FILM.......................... 65 1.2.1 The History of Anime................. 65 1.2.2 Technique and Aesthetic................ 69 1.2.3 Anime Viewers..................... 75 1.3 DIGITAL MANGA....................... 82 1.3.1 Participation, Subjectivity And Transport....... 82 i i i i i i i i i 1.3.2 Digital Graphic Novel: The Manga And Anime Con- vergence........................ 86 1.4 ANIME VIDEOGAMES.................... 90 1.4.1 Prolongament...................... 90 1.4.2 An Audience of Control................ 104 1.4.3 The Videogame-Film Symbiosis............ 106 1.5 COMMERCIALS AND VIDEOCLIPS............ 111 1.5.1 Advertisements Reconfigured............. 111 1.5.2 Anime Music Video And MTV Asia......... -

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

The Videogame Style Guide and Reference Manual

The International Game Journalists Association and Games Press Present THE VIDEOGAME STYLE GUIDE AND REFERENCE MANUAL DAVID THOMAS KYLE ORLAND SCOTT STEINBERG EDITED BY SCOTT JONES AND SHANA HERTZ THE VIDEOGAME STYLE GUIDE AND REFERENCE MANUAL All Rights Reserved © 2007 by Power Play Publishing—ISBN 978-1-4303-1305-2 No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means – graphic, electronic or mechanical – including photocopying, recording, taping or by any information storage retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher. Disclaimer The authors of this book have made every reasonable effort to ensure the accuracy and completeness of the information contained in the guide. Due to the nature of this work, editorial decisions about proper usage may not reflect specific business or legal uses. Neither the authors nor the publisher shall be liable or responsible to any person or entity with respects to any loss or damages arising from use of this manuscript. FOR WORK-RELATED DISCUSSION, OR TO CONTRIBUTE TO FUTURE STYLE GUIDE UPDATES: WWW.IGJA.ORG TO INSTANTLY REACH 22,000+ GAME JOURNALISTS, OR CUSTOM ONLINE PRESSROOMS: WWW.GAMESPRESS.COM TO ORDER ADDITIONAL COPIES OF THE VIDEOGAME STYLE GUIDE AND REFERENCE MANUAL PLEASE VISIT: WWW.GAMESTYLEGUIDE.COM ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Our thanks go out to the following people, without whom this book would not be possible: Matteo Bittanti, Brian Crecente, Mia Consalvo, John Davison, Libe Goad, Marc Saltzman, and Dean Takahashi for editorial review and input. Dan Hsu for the foreword. James Brightman for his support. Meghan Gallery for the front cover design. -

The Role of Audio for Immersion in Computer Games

CAPTIVATING SOUND THE ROLE OF AUDIO FOR IMMERSION IN COMPUTER GAMES by Sander Huiberts Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD at the Utrecht School of the Arts (HKU) Utrecht, The Netherlands and the University of Portsmouth Portsmouth, United Kingdom November 2010 Captivating Sound The role of audio for immersion in computer games © 2002‐2010 S.C. Huiberts Supervisor: Jan IJzermans Director of Studies: Tony Kalus Examiners: Dick Rijken, Dan Pinchbeck 2 Whilst registered as a candidate for the above degree, I have not been registered for any other research award. The results and conclusions embodied in this thesis are the work of the named candidate and have not been submitted for any other academic award. 3 Contents Abstract__________________________________________________________________________________________ 6 Preface___________________________________________________________________________________________ 7 1. Introduction __________________________________________________________________________________ 8 1.1 Motivation and background_____________________________________________________________ 8 1.2 Definition of research area and methodology _______________________________________ 11 Approach_________________________________________________________________________________ 11 Survey methods _________________________________________________________________________ 12 2. Game audio: the IEZA model ______________________________________________________________ 14 2.1 Understanding the structure -

Intersomatic Awareness in Game Design

The London School of Economics and Political Science Intersomatic Awareness in Game Design Siobhán Thomas A thesis submitted to the Department of Management of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. London, June 2015 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 66,515 words. 2 Abstract The aim of this qualitative research study was to develop an understanding of the lived experiences of game designers from the particular vantage point of intersomatic awareness. Intersomatic awareness is an interbodily awareness based on the premise that the body of another is always understood through the body of the self. While the term intersomatics is related to intersubjectivity, intercoordination, and intercorporeality it has a specific focus on somatic relationships between lived bodies. This research examined game designers’ body-oriented design practices, finding that within design work the body is a ground of experiential knowledge which is largely untapped. To access this knowledge a hermeneutic methodology was employed. The thesis presents a functional model of intersomatic awareness comprised of four dimensions: sensory ordering, sensory intensification, somatic imprinting, and somatic marking. -

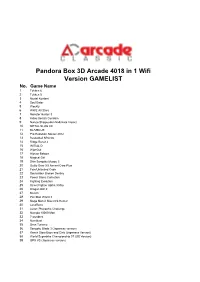

Pandora Box 3D Arcade 4018 in 1 Wifi Version GAMELIST No

Pandora Box 3D Arcade 4018 in 1 Wifi Version GAMELIST No. Game Name 1 Tekken 6 2 Tekken 5 3 Mortal Kombat 4 Soul Eater 5 Weekly 6 WWE All Stars 7 Monster Hunter 3 8 Kidou Senshi Gundam 9 Naruto Shippuuden Naltimate Impact 10 METAL SLUG XX 11 BLAZBLUE 12 Pro Evolution Soccer 2012 13 Basketball NBA 06 14 Ridge Racer 2 15 INITIAL D 16 WipeOut 17 Hitman Reborn 18 Magical Girl 19 Shin Sangoku Musou 5 20 Guilty Gear XX Accent Core Plus 21 Fate/Unlimited Code 22 Soulcalibur Broken Destiny 23 Power Stone Collection 24 Fighting Evolution 25 Street Fighter Alpha 3 Max 26 Dragon Ball Z 27 Bleach 28 Pac Man World 3 29 Mega Man X Maverick Hunter 30 LocoRoco 31 Luxor: Pharaoh's Challenge 32 Numpla 10000-Mon 33 7 wonders 34 Numblast 35 Gran Turismo 36 Sengoku Blade 3 (Japanese version) 37 Ranch Story Boys and Girls (Japanese Version) 38 World Superbike Championship 07 (US Version) 39 GPX VS (Japanese version) 40 Super Bubble Dragon (European Version) 41 Strike 1945 PLUS (US version) 42 Element Monster TD (Chinese Version) 43 Ranch Story Honey Village (Chinese Version) 44 Tianxiang Tieqiao (Chinese version) 45 Energy gemstone (European version) 46 Turtledove (Chinese version) 47 Cartoon hero VS Capcom 2 (American version) 48 Death or Life 2 (American Version) 49 VR Soldier Group 3 (European version) 50 Street Fighter Alpha 3 51 Street Fighter EX 52 Bloody Roar 2 53 Tekken 3 54 Tekken 2 55 Tekken 56 Mortal Kombat 4 57 Mortal Kombat 3 58 Mortal Kombat 2 59 The overlord continent 60 Oda Nobunaga 61 Super kitten 62 The battle of steel benevolence 63 Mech -

Game Developer at Least Three Reasons

>> PRODUCT REVIEWS: TECHEXCEL'S DEVTRACK 6.0 JUNE/JULY 2006 THE LEADING GAME INDUSTRY MAGAZINE >>E3 HIGHLIGHTS BEST IN SHOW AND WHAT Wii THINK >>EDGE OF THE WORLD STREAMING DATA FOR CONTINUOUS PLAY >>STATE OF THE INDUSTRY POSTMORTEM: IN-GAME ADVERTISING'S INDIGO FIERCE COMPETITION PROPHECY’S >>UNBREAKABLE BLOBS SHIFTING USING PHYSICS FOR VIEWPOINTS SQUISHY CHARACTERS Perforce. The fast SCM system. For developers who don’t like to wait. Tired of using a software configuration management system that stops you from checking in your digital assets? Perforce SCM is different: fast and powerful, elegant and clean. Perforce works at your speed. [Fast] Perforce's lock on performance rests firmly on three pillars of design. A carefully keyed relational database ensures a rapid response time for small operations plus high throughput when the requests get big - [Scalable] millions of files big. An efficient streaming network protocol minimizes the effects of latency and maximizes the benefits of bandwidth. And [Distributed] an intelligent, server-centric data model keeps both the database and network performing at top speed. It's your call. Do you want to work, or do you want to wait? Download a free copy of Perforce, no questions asked, from www.perforce.com. Free technical support is available throughout your evaluation. All trademarks used herein are either the trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. []CONTENTS JUNE/JULY 2006 VOLUME 13, NUMBER 6 FEATURES 11 STATE OF THE INDUSTRY: IN-GAME ADVERTISING Advertising in games is a burgeoning way to add revenue to games, closely tied to licensing, but quickly growing beyond that age-old practice. -

Sony Playstation 4

Sony PlayStation 4 Last Updated on September 24, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments Akiba's Trip 2 Acquire Aleste Collection M2 Aleste Collection: Game Gear Micro Include Edition M2 Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag Ubisoft Assault Suit Leynos extreme Co.,Ltd. Battle Princess Madelyn 3goo K.K. Battlefield 4 Electronic Arts Biohazard 7: Resident Evil Capcom Biomutant THQ Nordic Blade Arcus from Shining EX Sega Blair Witch: Limited Edition Blaster Master Zero Trilogy: MetaFight Chronicle Inti Creates Boku no Hiro Academia: One's Justice Bandai Namco Entertainment BQM: Blockquest Maker: Complete Edition Wonderland Kazakiri Call of Duty: Ghosts Activision Capcom Belt Action Collection Capcom Capcom Belt Action Collection: Collector's Box Capcom Clannad Prototype Closed Nightmare Nippon Ichi Software Coffee Talk Chorus Worldwide Cyber Troopers: Virtual On x Toaru Majutsu no Index: Toaru Majutsu no Dennou Senki Sega Daedalus: The Awakening of Golden Jazz: Limited Edition Arc System Works Darius Burst: Chronicle Saviours CS Kadokawa Games / Taito Dark Souls III Bandai Namco Games Dark Souls III: The Fire Fades Edition From Software Dark Souls: Remastered Bandai Namco Entertainment Dead or Alive Xtreme 3: Fortune KoeiTecmo Detroit: Become Human: Premium Edition Sony Interactive Entertainment Devil May Cry 4: Special Edition Capcom Digimon World: Next Order Bandai Namco Entertainment Dragon Quest XI: Sugisarishi Toki O Motomete Square Enix Dragon's Crown Pro: Royal Package Atlus Earth Defense Force: Iron Rain D3 Publisher ESP RA.DE. ψ M2 ESP RA.DE. ψ: Limited Edition M2 Farming Simulator 17 Intergrow Fatal Twelve Prototype Fell Seal: Arbiter's Mark 1C Entertainment / DMM Games Fighting EX Layer Arc System Works Final Fantasy Reishiki HD: Suzaku Edition Square Enix Final Fantasy Reishiki HD Square Enix Game Tengoku CruisinMix Special Kadokawa Games Game Tengoku CruisinMix Special: Gokuraku Box Kadokawa Games Game Tengoku: Cruisin Mix : Gentai Box Kadokawa Games, Ltd., Degic.. -

1 Learning and Video Games

Notes 1 Learning and Video Games 1 . h t t p : / / w w w . m a r i o w i k i . c o m / S u p e r _ M a r i o _ B r o s 2 . http://us.battle.net/wow/en/game/ 3 . http://www.ea.com/soccer/fifa/ps3 , accessed October 3, 2013. 4 . Electronic Arts, the company that distributes the video game, presents it on its Website http:// www.ea.com/soccer/fifa/ps3. It has also created excellent tutorials that can also be found on the website and in YouTube. Tutorials proliferate on the Internet, one of many may be this one: http://www.youtube.com/user/easportsfootball 5 . http://www.pong-story.com/atpong1.htm . The quoted text appears on this webpage, which gives a detailed and rigorous account of the origins of the history of the game Pong in an arcade system. 6 . An excellent description of this system may be found in http://www.pong-story.com/o1faq.txt . More information will be found in http://www.pong-story.com/odyssey.htm . Other sources of information may be found on Ralph Baer’s website: www.ralphbaer.com; the story of Odyssey can be read about in greater detail in www.pong-story.com . The photos come from http:// www.wisconsinhistory.org/museum/artifacts/archives/002558.asp . 7 . An excellent review of the history of consoles (1970–2006) may be found in http://www. thegameconsole.com/ 8 . More information can be found in http://nintendo.wikia.com/wiki/Game_%26_Watch . -

Final Media Kit 2006.Indd

Australian GamePro Media Kit CONTENTS 2 Introduction 5 Editorial 8 Specials 9 Marketing 12 Contacts I ntroduction Video gaming is the biggest entertainment medium on the planet. Not only does it bring in more cash than contemporaries such as Film and Music, but it is also the fastest growing, moving exponentially forward with the growth of technology and the continuing movement of consoles towards complete multimedia centres. With the release of the next-generation of Xbox 360, Nintendo Wii and PlayStation 3 console, the industry will be booming for the next 18 months. In 2006, the Australian video game market will consume well over $1billion from the game hungry public. This hungry public gets all the information it needs from the country’s premier multi- format publication, Australian GamePro Magazine. Average distribution 30,000 copies Cover Price $8.95 Average Pagination 100 Pages 02 SO, HOW IS GAMEPRO DIFFERENT? AsThe the launch facts above of Australian clearly indicate, GamePro the current was gamingsupported climate by isan as much aboutaggressive the mainstream, marketing casual and user advertising as it is about campaign the dedicated that hardcorewill enthusiastcontinue to— driveAustralian circulation. GamePro refl ects this. We recently underwent a huge redesign to bring our aesthetic style into line with the next- generation of console and gamer, giving it a broader, more appealing feel thatTARGET remains READERSHIP entirely game orientated while capturing the atmosphere of leadingEditorially, mainstream the publication titles. We havetargets also gamersadded new of sections, all ages ProSetUp and ProUpdate,(predominantly which providemales easy14 to access 30) and points will to run newcomers extensive to the coverage industry asof wellgaming as invaluable in all its information forms – Playstation®2, for veterans. -

Thesis Template

Bachelor’s thesis Information & Communications Technology 2021 Jarno Salo STORYTELLING THROUGH GAME AUDIO – case Juuret BACHELOR’S THESIS | ABSTRACT TURKU UNIVERSITY OF APPLIED SCIENCES Information & Communications Technology 2021 | 36 pages Jarno Salo STORYTELLING THROUGH GAME AUDIO • case Juuret Game audio is an integral part of the game development process. It helps greatly in creating immersion and building believable game worlds. Still it is often overlooked or just an afterthought. Badly made game audio can ruin even a good game. The purpose of this thesis was to design and create all the audio for a 3D adventure game called Juuret. It is the first game from a startup game company called FoxFail Creations. The audio was designed based on the research of music and game suggestions given by the commissioner. The design was then further improved after conducting literature research into types of game audio and their roles in creating immersion. After this the music and the ambience were carefully crafted using a Digital Audio Workstation and a MIDI keyboard. The sound effects were then recorded by using a microphone and a USB audio interface. The theoretical section of the thesis examines the evolution of game audio and related technology and how that has affected the ways game audio is created. The thesis also examines what types of game audio exist and the different roles they fill, how music becomes the soundtrack for the player’s actions, how ambience fills the game world with details and how sound effects give feedback to the player about what is happening. Finally the thesis examines what type of workflow to expect when working in an audio role in the game industry. -

Locoroco for Psp Iso Download Locoroco for Psp Iso Download

locoroco for psp iso download Locoroco for psp iso download. LocoRoco is an innovative 2D platform/action game available exclusively for the PSP. Featuring unique controls utilizing the “L” and “R” shoulder buttons, players are tasked with controlling via “tilting or bumping” the landscape of the LocoRoco in order to help them navigate through the level and keep them out of harm’s way. With more than 40 stages, players control and guide the LocoRoco through vibrant, thriving and lush worlds filled with slippery slopes, swing ropes , and more. Featuring six different types of LocoRoco that include their own voices and actions, players will be enchanted by captivating music that communicates the joyous world of these LocoRoco. In addition, LocoRoco features the rewarding LocoHouse, three mini-games , and wireless features. The peaceful world of the LocoRoco are under attack by the not-so-nice Moja Corps. These evil outer space creatures want nothing but to capture the blissful LocoRoco and take them from their land of blowing flowers, lively creatures and pastel scenery. As the planet where the LocoRoco inhabit, players must tilt, roll and bounce the LocoRoco to safety. LocoRoco Hi. LocoRoco's HD re-release is now available worldwide. The Point - Should you buy a VITA? Danny explores the uneasy history of PlayStation portables, and wonders if now is the perfect time to get a VITA. Behind the Games: Tsutomu Kouno. Sony's creative mind behind Loco Roco talks about flying bicycles, an indoor snowboarding bar, and enormous glass earrings in this installment of our Behind the Games feature.