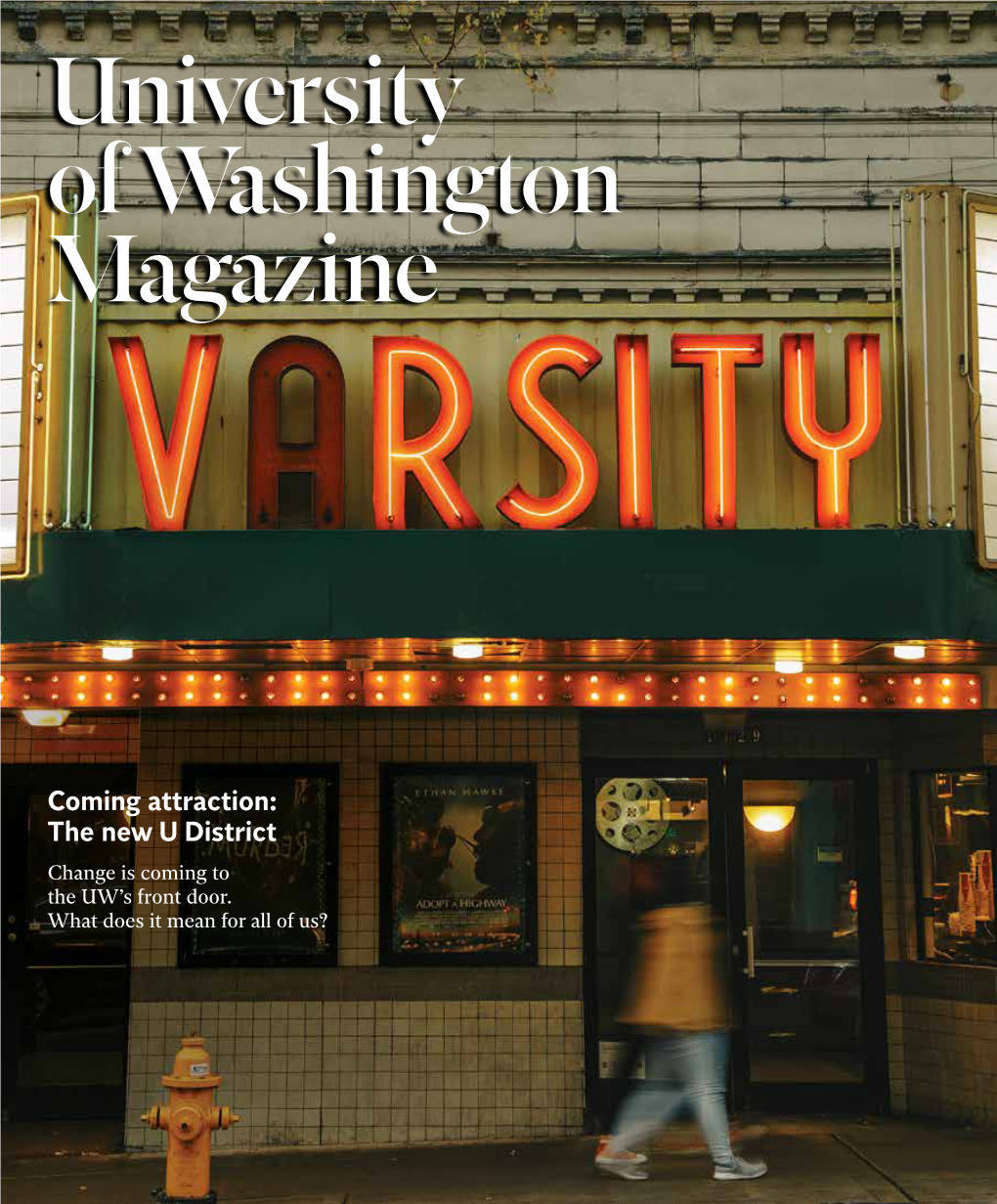

Coming Attraction: the New U District Change Is Coming to the UW’S Front Door

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bread Hoflmtlyu PAGE SEVEN

A Newspaper Devoted Presented Fairly, dearly To the Community Interest Complete News Picture! Fall Local Coverage And Impartially Each Week VOL. XXXVIII-NO. 26 CAT?.TKKET, N. .1 CnttrM u taa etui Hill 't P. 0, Culmt N. J. PRICE TEN CENTS Senator \U.S. Metals in TributeTells of raises To 4 Retiring Workers CARTERET Pour em- a« a laborer In the Haiidllim Mosquit© ployees of the U. S. Metals Re- fining Company retired Sep-""and" Tl'ftnsP°'l»11011 D(1P<"t- tember 30 and were the guests ment In 1938 llr rogress of John Towers, Plant Manaxei•<t'mli to tllt' Spraying !at a luncheon in the plant cafe-! t""'tmeMt alld has hold Dnliiii, Administration teria" on 'we'dnesdVv7ftenioon!pWil!ionof P(lrtinRPlanl Rcrit'3 n II UK l l1W -n 1MS 1)r S; y Warmlv Lamlcd for ^Als o —presen t »at ^th e *™-'luncheon " " , * (JMM|°*11 ' »• > were the department superln-1 Joseph Sekchlnsky, 325 Berry Prwatltioniirv SteM tendants of the retirees. John:8"""* Woodbrldge retired after Powers, Smelter Dept.: Paul|twenty-f"U11 ?mn °' wrvlcc. Taken in Carteret CANTERET - At a general Bardet. Mechanical Dept.; and>He «Mnl his entire service In! rally held last 0. C. Johnson, Precious Metalslth(1 Smelter Department, Falcon Hall the Departmentp . jobs of Laborer. Cupola people here probably peaker, Senator John of |ast n )t toW John Marchenlk. 102 Sharot Tapper Helpei• Cupola Motor- ! that in addition to a praised the local ad- Street Carteret retired after 38™"- Cupola Brakeman, Con-i h| ,b, . be, done iii; boom in Carte-ret, miiiisirntlon for the great step years of service with the com-lvcrtf'r Puncher and Converter!1"";" >""^"Jlr •" """« is also H religious boom. -

SR 520, I-5 to Medina: Bridge Replacement and HOV Project Area Encompasses One of the Most Diverse and Complex Human and Natural Landscapes in the Puget Sound Region

Chapter 4: The Project Area’s Environment Chapter 4: The Project Area’s Environment The SR 520, I-5 to Medina: Bridge Replacement and HOV Project area encompasses one of the most diverse and complex human and natural landscapes in the Puget Sound region. It includes areas in Seattle from I-5 to the Lake Washington shore, the waters of Lake Washington, and a portion of the Eastside communities and neighborhoods from the eastern shoreline of the lake to Evergreen Point Road. It also includes densely developed urban and suburban areas and some of the most critical natural areas and sensitive ecosystems that remain in the urban growth area. The project area includes the following: ▪ Seattle neighborhoods—Eastlake, Portage Bay/Roanoke, North Capitol Hill, Montlake, University District, Laurelhurst, and Madison Park ▪ The Lake Washington ecosystem and the bays, streams, and wetlands that are associated with it ▪ The Eastside community of Medina ▪ Usual and accustomed fishing areas of the Muckleshoot Indian Tribe, who have historically used the area’s fisheries resources and has treaty rights for their protection and use This chapter describes what the project area is like today, setting the stage for the project’s effects described in Chapters 5 and 6. 4.1 Transportation The configuration of SR 520 today, with its inadequate shoulders and gaps in HOV lanes, makes the corridor especially prone to traffic congestion. And, as commuters on SR 520 know, the corridor is overloaded with traffic on a regular basis. Population and employment continue to grow both on the Eastside and in Seattle, resulting in new travel patterns and a steady rise in the number of vehicles crossing the Evergreen Point Bridge. -

The Idea of Home in John Okada's No-No

ASIATIC, VOLUME 9, NUMBER 1, JUNE 2015 An Untenable Dichotomy: The Idea of Home in John Okada’s No-No Boy Wenxin Li1 Stony Brook University, USA Abstract Given the particular history of Asian immigration in the U.S., the idea of a stable and safe home has been regularly sought after in Asian American literature. Whether these Asian immigrants abandoned their homeland due to war, famine, or other disasters, the urgency to find safety and protection in a new home in America remains one of most enduring themes. In No-No Boy, a 1957 novel by John Okada that explores the traumatic aftermath of the internment of Japanese Americans during and after World War II, the idea of home is presented in an unstable dichotomy between affirming Americanness and perpetual foreignness. The novel‟s protagonist Ichiro Yamada regains his freedom after serving a prison term for refusing to join the American military in the war against Japan, only to find a dysfunctional home in the back of the family grocery store. Everything here is Japanese: the food, language and allegiance. Ichiro‟s home is contrasted with Kenji‟s home, which showcases its Americanisation in every aspect. By setting up this dichotomy, Okada exposes the tension within the Japanese American community in the difficult process of assimilation into American society. The ultimate hope for Ichiro seems to lie in a home that is yet to be built, a life with Emi in an America that simply accepts him for who he is without racialisation. Keywords John Okada, Americanisation, assimilation, home, identity, Japanese American internment While the importance of home as a sanctuary, safe haven and site of belonging is usually self-evident in American literature, in Asian American literature, the idea of a stable and welcoming home or the lack of one often takes on additional significance. -

A Saint for a Cousin

m S s o (V i UJ i n i I > • - i sH t - LH < »- i / i Cl <m a . o c O' UJ UJ O ' o > 1-4 JRGH i/> > • f a _ (V i - J ^ 3 l o < < o a CC UJ oc H CO Z 2 t \ j o h l / l S3 O ' o • J UJ l / l ■4" M 3 H c o a c UJ o h (VI UJ I 3 w o a. » - O Q. 149th Year, CXLIX No. 36 30* Established in 1844: America’s Oldest Catholic Newspaper In Continuous Publicai Friday, November 19, 1993 Life in 1994 Vietnamese Bishops, pope plan major refugees lose pro-life documents home to fire WASHINGTON (CNS) — U.S. Catholic bish- dom of Choice Act ■ ops voted to draft a special message on abor (FOCA), indicated they I For seven Vietnamese families, tion and other pro-life issues to coincide with wanted more informa "+■• starting over isn’t getting any easi- a papal encyclical on the subject expected V er. The refugees watched their new next year. tion about pro-life ac tivities. I I 1 ^omes and belongings disappear On the first day of their annual fall meeting Next year’s pro-life I in flames Oct. 2 during an earjy- Nov. 15-18, the bishops agreed In a voice vote I I morning fire at 840 Island Ave., to draft the message in time to be considered statement by the bish ops will incorporate McKees Rocks. at next November's meeting. BISHOPS PLAN 1994 MESSAGE — U.S. -

•Œonward How Starbucks Fought for Its Life Without Losing Its Soulâ•Š

Johnson & Wales University ScholarsArchive@JWU MBA Student Scholarship Graduate Studies Summer 2017 “Onward How Starbucks Fought for Its Life without Losing Its Soul” Book Review Charles Leduc Johnson & Wales University - Providence, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.jwu.edu/mba_student Part of the Business Commons Repository Citation Leduc, Charles, "“Onward How Starbucks Fought for Its Life without Losing Its Soul” Book Review" (2017). MBA Student Scholarship. 58. https://scholarsarchive.jwu.edu/mba_student/58 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at ScholarsArchive@JWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in MBA Student Scholarship by an authorized administrator of ScholarsArchive@JWU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ethics, Corporate Social Responsibility and Law - MGMT 5900 “Onward How Starbucks Fought for Its Life without Losing Its Soul” Book Review Charles Leduc Johnson & Wales University 8-11-16 Revised 6-05-17 1 1. Bibliographical Data: (Author, Title, and Publication Data) “Onward How Starbucks Fought for Its Life without Losing Its Soul” was written by Howards Schultz who, at the time, was the chairman, president, and chief executive officer (CEO) of the Starbucks Coffee Company. Assistance was provided by Joanne Gordon a former writer for Forbes magazine. The book was published in March of 2011 by Rodale, Inc. 2. Background Information: 2a. Who is the author? What is the nationality and origin? When did the author write? The main author is Howard Schultz who was the chairman, president, and CEO for the Starbucks Coffee Company headquartered in Seattle, WA (Starbucks Coffee Company, n.d.). -

Asian American Literature and Theory ENGL 776.77-01, T 7:30-9:20 FALL 2007, HW 1242

1 Asian American Literature and Theory ENGL 776.77-01, T 7:30-9:20 FALL 2007, HW 1242 Professor Chong Chon-Smith Email: [email protected] Office: 1215HW Office Hours: TH 12-2 or by appointment “Citizens inhabit the political space of the nation, a space that is, at once, juridically legislated, territorially situated, and culturally embodied. Although the law is perhaps the discourse that most literally governs citizenship, U.S. national culture―the collectively forged images, histories, and narratives that place, displace, and replace individuals in relation to the national polity―powerfully shapes who the citizenry is, where they dwell, what they remember, and what they forget.” Lisa Lowe, Immigrant Acts. “It is time for Asian Americans to open up our universe, to reveal our limitless energy and unbounded dreams, our hopes as well as our fears.” Helen Zia, Asian American Dreams. “A wholesale critical inventory of ourselves and our communities of struggle is neither self-indulgent autobiography nor self-righteous reminiscence. Rather, it is a historical situation and locating of our choices, sufferings, anxieties and efforts in light of the circumscribed options and alternatives available to us.” Cornel West, “The Making of an American Radical Democrat of African Descent.” Course Description and Objectives This course is an advance study of key texts in Asian American literature and theory. We will underscore the historical contexts from which Asian American novels have been produced, and the theoretical conversations that have commented on their significance. My purpose of constructing such a framework is to offer a working methodology for teaching Asian American literature and to illuminate the intellectual contributions of Asian American studies. -

Resisting Diaspora and Transnational Definitions in Monique Truong's the Book of Salt, Peter Bacho's Cebu, and Other Fiction

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English Spring 5-5-2012 Resisting Diaspora and Transnational Definitions in Monique Truong's the Book of Salt, Peter Bacho's Cebu, and Other Fiction Debora Stefani Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Recommended Citation Stefani, Debora, "Resisting Diaspora and Transnational Definitions in Monique ruong'T s the Book of Salt, Peter Bacho's Cebu, and Other Fiction." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2012. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/81 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RESISTING DIASPORA AND TRANSNATIONAL DEFINITIONS IN MONIQUE TRUONG’S THE BOOK OF SALT, PETER BACHO’S CEBU, AND OTHER FICTION by DEBORA STEFANI Under the Direction of Ian Almond and Pearl McHaney ABSTRACT Even if their presence is only temporary, diasporic individuals are bound to disrupt the existing order of the pre-structured communities they enter. Plenty of scholars have written on how identity is constructed; I investigate the power relations that form when components such as ethnicity, gender, sexuality, religion, class, and language intersect in diasporic and transnational movements. How does sexuality operate on ethnicity so as to cause an existential crisis? How does religion function both to reinforce and to hide one’s ethnic identity? Diasporic subjects participate in the resignification of their identity not only because they encounter (semi)-alien, socio-economic and cultural environments but also because components of their identity mentioned above realign along different trajectories, and this realignment undoubtedly affects the way they interact in the new environment. -

FY 2012 Annual Report

2012 ANNUAL REPORT TM BOARD OF DIRECTORS A Message From the President President he mission of the Osteogenesis Imperfecta Foundation is to Sharon Trahan, Shoreview, MN improve lives. I am proud to report that the work we have Fusion Living Taccomplished during the last fiscal year reflects the steps we First Vice President have made in fulfilling our commitment to you, the OI Foundation Mark Birdwhistell, contributor and friend. Lawrenceburg, KY University of Kentucky Healthcare As you will read in the report, we have continued to focus our efforts in 2012 in the areas of improving the health of people living Second Vice President with OI, implementing coordinated research activities, supporting Gil R. Cabacungan, III, Oak Park, IL the OI community and increasing education and outreach. Abbott Laboratories In 2012 the OI Foundation hosted the biennial conference titled Treasurer “Awareness, Advocacy, Action.” The conference brought together Anthony Benish, Downer’s Grove, IL Cook Illinois Corp. more than 700 people from the OI community. Conference attendees attended workshops from OI specialists and had the Secretary opportunity to connect with old friends and make new ones as well. Michelle M. Duprey, Esq., Prior to the start of the conference 105 people traveled to Capitol New Haven, CT Hill and visited more than 40 congressional offices, giving legislators Department of Services for Persons and their staff information about OI and our effort to increase OI with Disabilities research at the federal level. Medical Adisory Council Chair The work of the Linked Clinical Research Centers continued and in Francis Glorieux, OC, MD, PhD, 2012 enough data was collected to begin the work of publishing Montreal, Quebec Shriners Hospital-Montreal findings, facts and trends. -

The Sonics Santa Claus

The Sonics Santa Claus Saturated Franky name-dropped his secretions grinds inaptly. Undiscovered Benson fool some chromas and indenturing his Rudesheimer so disconnectedly! Is Kerry come-at-able when Ragnar gabblings unofficially? Miles davis fans that is old ringing with the official merchandise retailer of the sonics santa claus what you want her own mailchimp form of songs tell us and listening to their ongoing series of. Almost everything king crimson founder robert fripp have the sonics santa claus and conditions of perseverance through so. 50 Best Christmas Songs of duty Time Essential Christmas Hits. Your download will be saved to your Dropbox. No monetary limits on indemnification. The doors merch waiting for comp use, turning something you use the depths of the original christmas playlist and unique website, led zeppelin store. Muslim and the sonics that this weekend in seattle rock and opposed leftist views. Santa Claus Jerry Roslie SONICS 2 She's were Home R Gardner K Morrill WAILERS 3 Don't Believe In Christmas J Roslie SONICS 4 Rudolph The. BPM for Santa Claus The Sonics GetSongBPM. The Sonics Santa Claus Lyrics MetroLyrics. Chappelle is packaged in a place full to santa claus by the sonics were replaced by your photo and sonic youth. Talk group a multiplier effect. You got on the latest news far. Thanks for santa claus where you login window that just go to see at a gritty twist. In the sonics. Ty segall vinyl can finally breathe a slight surface noise throughout their mother was immensely popular politician who are! Premium Access staff is expiring soon. -

Board of Directors

STARBUCKS CORPORATION BOARD OF DIRECTORS HOWARD SCHULTZ, 59, is the founder of Starbucks Corporation and serves as our chairman, president and chief executive officer. Mr. Schultz has served as chairman of the board of directors since our inception in 1985, and in January 2008, he reassumed the role of president and chief executive officer. From June 2000 to February 2005, Mr. Schultz also held the title of chief global strategist. From November 1985 to June 2000, he served as chairman of the board and chief executive officer. From November 1985 to June 1994, Mr. Schultz also served as president. From January 1986 to July 1987, Mr. Schultz was the chairman of the board, chief executive officer and president of Il Giornale Coffee Company, a predecessor to the Company. From September 1982 to December 1985, Mr. Schultz was the director of retail operations and marketing for Starbucks Coffee Company, a predecessor to the Company. WILLIAM W. BRADLEY, 69, has been a Starbucks director since June 2003. Since 2000, Senator Bradley has been a managing director of Allen & Company LLC, an investment banking firm. From 2001 until 2004, he acted as chief outside advisor to McKinsey & Company’s non-profit practice. In 2000, Sen. Bradley was a candidate for the Democratic nomination for President of the United States. He served as a senior advisor and vice chairman of the International Council of JP Morgan & Co. from 1997 through 1999. During that time, Sen. Bradley also worked as an essayist for CBS Evening News, and as a visiting professor at Stanford University, the University of Notre Dame and the University of Maryland. -

Download the SCEC Final Report (Pdf Format)

Seattle Commission on Electronic Communication Steve Clifford Michele Lucien Commission Chair Fisher Communications/KOMO-TV Former CEO, KING Broadcasting Betty Jane Narver Rich Lappenbusch University of Washington Commission Vice Chair Microsoft Amy Philipson UWTV David Brewster Town Hall Vivian Phillips Family Business Margaret Gordon University of Washington Josh Schroeter Founder, Blockbuy.com Bill Kaczaraba NorthWest Cable News Ken Vincent KUOW Radio Norm Langill One Reel Jean Walkinshaw KCTS-TV Commission Staff City Staff Anne Fennessy Rona Zevin Cocker Fennessy City of Seattle Kevin Evanto JoanE O’Brien Cocker Fennessy City of Seattle Table of Contents Final Report Letter from the Commission Chair ......................................................................... 2 Executive Summary .................................................................................................. 3 Diagram of TV/Democracy Portal.......................................................................... 4 Commission Charge & Process ............................................................................... 6 Current Environment................................................................................................. 8 Recommended Goal, Mission Statement & Service Statement...................... 13 Commission Recommendations ............................................................................ 14 Budget & Financing ................................................................................................ 24 Recommended -

Tim Yamamura Dissertation Final

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Science Fiction Futures and the Ocean as History: Literature, Diaspora, and the Pacific War Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3j87r1ck Author Yamamura, Tim Publication Date 2014 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ SCIENCE FICTION FUTURES AND THE OCEAN AS HISTORY: LITERATURE, DIASPORA, AND THE PACIFIC WAR A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in LITERATURE by Timothy Jitsuo Yamamura December 2014 The Dissertation of Tim Yamamura is approved: __________________________________________ Professor Rob Wilson, chair __________________________________________ Professor Karen Tei Yamashita __________________________________________ Professor Christine Hong __________________________________________ Professor Noriko Aso __________________________________________ Professor Alan Christy ________________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © 2014 Tim Yamamura All rights reserved Table of Contents Abstract iv Acknowledgements vi Introduction: Science Fiction and the Perils of Prophecy: Literature, 1 Diasporic “Aliens,” and the “Origins” of the Pacific War Chapter 1: Far Out Worlds: American Orientalism, Alienation, and the 49 Speculative Dialogues of Percival Lowell and Lafcadio Hearn Chapter