Socially Engaged Street Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feature Article} {Profile}

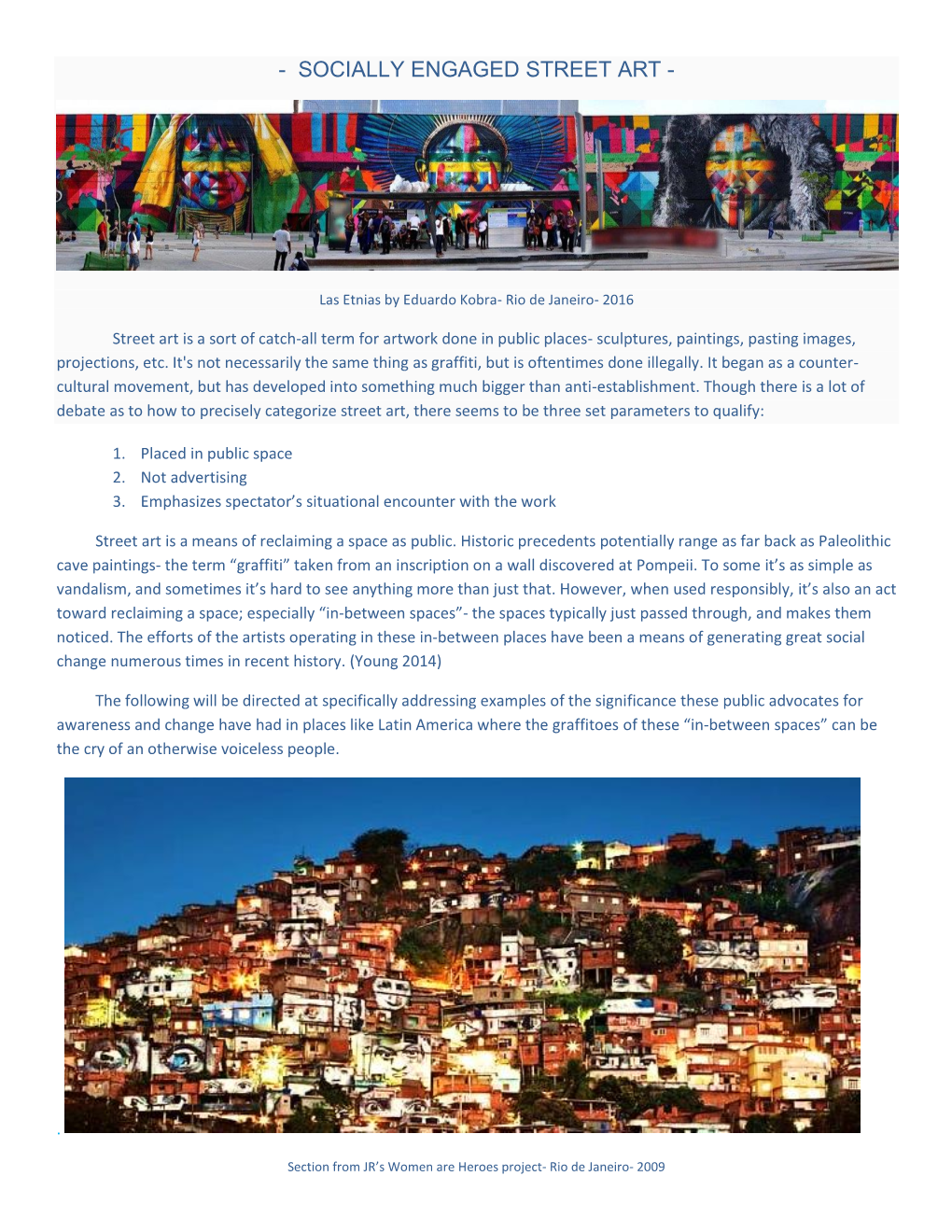

{PROFILE} {PROFILE} {FEATURE ARTICLE} {PROFILE} 28 {OUTLINE} ISSUE 4, 2013 Photo Credit: Sharon Givoni {FEATURE ARTICLE} Street Art: Another Brick in the Copyright Wall “A visual conversation between many voices”, street art is “colourful, raw, witty” 1 and thought-provoking... however perhaps most importantly, a potential new source of income for illustrators. Here, Melbourne-based copyright lawyer, Sharon Givoni, considers how the laws relating to street art may be relevant to illustrators. She tries to make you “street smart” in an environment where increasingly such creations are not only tolerated, but even celebrated. 1 Street Art Melbourne, Lou Chamberlin, Explore Australia Publishing Pty Ltd, 2013, Comments made on the back cover. It canvasses: 1. copyright issues; 2. moral rights laws; and 3. the conflict between intellectual property and real property. Why this topic? One only needs to drive down the streets of Melbourne to realise that urban art is so ubiquitous that the city has been unofficially dubbed the stencil graffiti capital. Street art has rapidly gained momentum as an art form in its own right. So much so that Melbourne-based street artist Luke Cornish (aka E.L.K.) was an Archibald finalist in 2012 with his street art inspired stencilled portrait.1 The work, according to Bonham’s Auction House, was recently sold at auction for AUD $34,160.00.2 Stencil seen in the London suburb of Shoreditch. Photo Credit: Chris Scott Artist: Unknown It is therefore becoming increasingly important that illustra- tors working within the street art scene understand how the law (particularly copyright law) may apply. -

Moral Rights: the Anti-Rebellion Graffiti Heritage of 5Pointz Richard H

digitalcommons.nyls.edu Faculty Scholarship Articles & Chapters 2018 Moral Rights: The Anti-Rebellion Graffiti Heritage of 5Pointz Richard H. Chused New York Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/fac_articles_chapters Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Land Use Law Commons, and the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation Chused, Richard H., "Moral Rights: The Anti-Rebellion Graffiti Heritage of 5Pointz" (2018). Articles & Chapters. 1172. https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/fac_articles_chapters/1172 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles & Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@NYLS. Moral Rights: The Anti-Rebellion Graffiti Heritage of 5Pointz Richard Chused* INTRODUCTION Graffiti has blossomed into far more than spray-painted tags and quickly vanishing pieces on abandoned buildings, trains, subway cars, and remote underpasses painted by rebellious urbanites. In some quarters, it has become high art. Works by acclaimed street artists Shepard Fairey, Jean-Michel Basquiat,2 and Banksy,3 among many others, are now highly prized. Though Banksy has consistently refused to sell his work and objected to others doing so, works of other * Professor of Law, New York Law School. I must give a heartfelt, special thank you to my artist wife and muse, Elizabeth Langer, for her careful reading and constructive critiques of various drafts of this essay. Her insights about art are deeply embedded in both this paper and my psyche. Familial thanks are also due to our son, Benjamin Chused, whose knowledge of the graffiti world was especially helpful in composing this paper. -

Anti-Trump Street Art Along the US-Mexico Border" (2019)

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Center for Advanced Research in Global CARGC Papers Communication (CARGC) 8-2019 Dreamers and Donald Trump: Anti-Trump Street Art Along the US- Mexico Border Julia Becker [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/cargc_papers Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Becker, Julia, "Dreamers and Donald Trump: Anti-Trump Street Art Along the US-Mexico Border" (2019). CARGC Papers. 11. https://repository.upenn.edu/cargc_papers/11 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/cargc_papers/11 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dreamers and Donald Trump: Anti-Trump Street Art Along the US-Mexico Border Description What tools are at hand for residents living on the US-Mexico border to respond to mainstream news and presidential-driven narratives about immigrants, immigration, and the border region? How do citizen activists living far from the border contend with President Trump’s promises to “build the wall,” enact immigration bans, and deport the millions of undocumented immigrants living in the United States? How do situated, highly localized pieces of street art engage with new media to become creative and internationally resonant sites of defiance? CARGC Paper 11, “Dreamers and Donald Trump: Anti-Trump Street Art Along the US-Mexico Border,” answers these questions through a textual analysis of street art in the border region. Drawing on her Undergraduate Honors Thesis and fieldwork she conducted at border sites in Texas, California, and Mexico in early 2018, former CARGC Undergraduate Fellow Julia Becker takes stock of the political climate in the US and Mexico, examines Donald Trump’s rhetoric about immigration, and analyzes how street art situated at the border becomes a medium of protest in response to that rhetoric. -

The Evolution of Graffiti Art

Journal of Conscious Evolution Volume 11 Article 1 Issue 11 Issue 11/ 2014 June 2018 From Primitive to Integral: The volutE ion of Graffiti Art White, Ashanti Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/cejournal Part of the Clinical Psychology Commons, Cognition and Perception Commons, Cognitive Psychology Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Liberal Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons, Social Psychology Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, Sociology of Religion Commons, and the Transpersonal Psychology Commons Recommended Citation White, Ashanti (2018) "From Primitive to Integral: The vE olution of Graffiti Art," Journal of Conscious Evolution: Vol. 11 : Iss. 11 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/cejournal/vol11/iss11/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Conscious Evolution by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. : From Primitive to Integral: The Evolution of Graffiti Art Journal of Conscious Evolution Issue 11, 2014 From Primitive to Integral: The Evolution of Graffiti Art Ashanti White California Institute of Integral Studies ABSTRACT Art is about expression. It is neither right nor wrong. It can be beautiful or distorted. It can be influenced by pain or pleasure. It can also be motivated for selfish or selfless reasons. It is expression. Arguably, no artistic movement encompasses this more than graffiti art. -

Graffiti De Oz Montanía, Fotografía De Xoan García Huguet

CUADERNOS SALAZAR #1 DISLOCACIONES CENTro CULTURAL DE ESPAÑA Juan DE SALAZAR Tacuary 745 y Herrera 834 CUADERNOS SALAZAR #1 Asunción (Paraguay) +59521449921 [email protected] DISLOCACIONES Dislocaciones www.juande salazar.org.py Tw: @ccejs_py Fb: CCEJS_AECID Paraguay Los cuadernos del Salazar se editan bajo licencia Creative Commons: Reconocimiento del autor Sin fines de lucro Sin obra derivada CUADERNOS SALAZAR #1 DISLOCACIONES EMBAJADA DE ESPAÑA Embajador—Diego Bermejo Romero de Terreros CENTRO CULTURAL DE ESPAÑA JUAN DE SALAZAR Directora—Eloísa Vaello Marco COLECCIÓN CUADERNOS SALAZAR #1 DISLOCACIONES Coordinación y edición—Ruth Osorio Cuidados de la edición y corrección—Toni García Diseño editorial—Alejandro Valdez, Ana Ayala, Paolo Herrera. Autores que colaboran en éste número —Azeta, Oz Montanía, Adriana Almada, Rosa Palazón, Vladimir Velázquez, Lía Colombino, Luís Caputo, Daniel Mittmann, Lorena Cabrera, Rafo Vera, Fros, Rocío Céspedes, Kast, Kleina Mc, Leda Sostoa, Legasy, Lonchi Romero, PrizPrazPruz, Mali, Lucas We, Eulo García, María Glausser, Saturn, Rafael Scorza, Walter Souza, Eddy Graff, Vidal González, Yana Vallejo, Eloísa Vaello Marco, Ruth Osorio. Agradecimientos a Patty Acuña, una de las fundadoras de la Casa de los Payasos, quien con su luz sigue irradiando, a Yamil Ríos, referente de la cultura hip hop, por el apoyo y colaboración y a Patricio Dobrée. Imagen de portada—Graffiti de Oz Montanía, Fotografía de Xoan García Huguet. Impreso en ARTE NUEVO 1.000 Ejemplares Asunción, 17 de octubre de 2013. A los soñadores -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:__June 5, 2007_______ I, Jennifer Lynn Hardin_______________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Masters of Arts in: Art History It is entitled: “ A Season in Hell”: David Wojnarowicz’s Rimbaud in New York Series (1978-79) This work and its defense approved by: Chair: Dr.Kimberly Paice______________ Dr. Michael Carrasco___________ Dr. Mikiko Hirayama____________ _______________________________ _______________________________ “A Season in Hell”: David Wojnarowicz’s Rimbaud In New York Series (1978-79) A thesis submitted to the Art History Faculty of the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning University of Cincinnati In candidacy for the degree of Masters of Arts in Art History Jennifer Hardin June 2007 Advisor: Dr. Kimberly Paice Abstract David Wojnarowicz (1954-1992) was an interdisciplinary artist who rejected traditional scholarship and was suspicious of institutions. Wojnarowicz’s Arthur Rimbaud in New York series (1978-79) is his earliest complete body of work. In the series a friend wears the visage of the French symbolist poet. My discussion of the photographs involves how they convey Wojnarowicz’s notion of the city. In chapter one I discuss Rimbaud’s conception of the modern city and how Wojnarowicz evokes the figure of the flâneur in establishing a link with nineteenth century Paris. In the final chapters I address the issue of the control of the city and an individual’s right to the city. In chapter two I draw a connection between the renovations of Paris by Baron George Eugène Haussman and the gentrification Wojnarowicz witnessed of the Lower East side. -

The Legitimation of Street Art in Amsterdam the Role of Street Art Today Museum

The legitimation of street art in Amsterdam The role of Street Art Today Museum Student Name: Giovanna Di Giacomo Student Number: 459774 Supervisor: Dr. D. S. Ferreira Second Reader: Dr. P.P.L. Berkers Master in Arts, Culture & Society Erasmus School of History, Culture and Communication Erasmus University Rotterdam Master Thesis 12 June 2017 The legitimation of street art in Amsterdam: The role of Street Art Today Museum ABSTRACT Street art is originally a rebellious, illegal and underground practice that emerged on the city walls. Even though this cultural manifestation appeared outside of the art world, it is frequently found in art institutions. Considering that what is placed in such settings is more acknowledged as art, street art is framed by artistic and cultural value when exhibited in art galleries and museums. In such a way, it is moving from the periphery towards a central position in the art world. Due to the anti-institutional discourse that was originally part of street art, there is a controversy regarding its presence in art institutions, since this can be considered a threat to its marginal character. Currently, the organization Street Art Today is building a museum dedicated exclusively to street art in the city of Amsterdam. Therefore, the present thesis focuses on this case, in order to explore how a formerly rebellious artistic expression can be acknowledged as an art form by the traditional art world, without losing its roots. Thus, the following research question was addressed: What is the role of Street Art Today museum in the legitimation of street art in Amsterdam? In order to provide an answer, ten semi-structured, in-depth interviews were conducted with actors from the Amsterdam’s street art scene. -

STREET ART/SOKAK SANATI Sokak Sanatı, Halka Açık Yerlerde Yapılan Her Türlü Sanatsal Aktiviteye Deniyor

STREET ART/SOKAK SANATI Sokak sanatı, halka açık yerlerde yapılan her türlü sanatsal aktiviteye deniyor. Yalnız klasik sokak sanatı tanımına, devlet destekli , sponsorlu çalışmalar girmiyor. Mesela Şehir Tiyatroları gidip sokakta bir gösteri yaparsa, bu sokak sanatı olmuyor. (Anonim, 2008) Almanya-Köln (Orijinal, Ocak 2013) Sokak sanatı, graffiti, şablon (stencil graffiti), sticker art, street poster art, video projection, wheatpasting ve sokakta yapılan pantomim, tiyatro, illüzyon, hava akrobasisi, juggling gibi bir çok sanatı içermektedir. (Anonim, 2008) İtalya-Roma (Orijinal, Aralık 2012) Almanya-Köln (Orijinal, Ocak 2013) Hepsinde bir aktivizm, bir mesaj kaygısı ya da gelişmiş bir görsel lezzet var. Bu alternatif üreyen sanat anlayışına "Culture jamming" deniyor. Almanya-Hamburg (Orijinal, Kasım 2012) Bazı sokak sanatçıları, galerilerle ilgilenmeyen geniş kitlelere ulaşabilecekleri boş birer alan olarak sokakları düşünürken, bazıları ise bunun zorluğunu ve risklerini seviyor. Geleneksel sanat, bir galeriden diğerine taşınabilir ama sokak sanatı olduğu yere ait bir aidiyet barındırmaktadır. (Anonim, 2012) İtalya-Floransa (Orijinal, Aralık 2012) Modern sokak sanatı, üzerine çalışılan yerin dokusunu da taşıyor ve bu yüzden biyolojik bir varlık olarak görülüyor. Para veya ün söz konusu değil, sadece artistik kaygılar ve insanların beynini gıdıklama isteğinden bahsedilebilir. (Anonim, 2012) Sokak sanatçısı mevcut sanat tanımını değiştirme arzusunda değildir fakat kendi dili ile mevcut çevreyi sorgulama eylemindedir. Sokak sanatında işin kendisinden çok, önünden geçen insanlara neler hissettirdiği önemli. (Anonim, 2008) İstanbul Genellikle çağdaş kamusal sanat çalışmasını bölgesel graffiti, vandalizm ve ortak sanattan ayırt etmek için kullanılır. Banksy savaş karşıtı, çevreci, hayvan haklarını savunan tüketim çılgınlıgını elestiren, dünyanın pek çok yerinde yaptıgı duvar resimleri ile tanınıyor. Estetik beğeniyi hitap eden ve aynı zamanda protesto yönü ağır basan kendine has tarzını yaratmayı bilmiştir. -

Defining and Understanding Street Art As It Relates to Racial Justice In

Décor-racial: Defining and Understanding Street Art as it Relates to Racial Justice in Baltimore, Maryland A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Meredith K. Stone August 2017 © 2017 Meredith K. Stone All Rights Reserved 2 This thesis titled Décor-racial: Defining and Understanding Street Art as it Relates to Racial Justice in Baltimore, Maryland by MEREDITH K. STONE has been approved for the Department of Geography and the College of Arts and Sciences by Geoffrey L. Buckley Professor of Geography Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT STONE, MEREDITH K., M.A., August 2017, Geography Décor-racial: Defining and Understanding Street Art as it Relates to Racial Justice in Baltimore, Maryland Director of Thesis: Geoffrey L. Buckley Baltimore gained national attention in the spring of 2015 after Freddie Gray, a young black man, died while in police custody. This event sparked protests in Baltimore and other cities in the U.S. and soon became associated with the Black Lives Matter movement. One way to bring communities together, give voice to disenfranchised residents, and broadcast political and social justice messages is through street art. While it is difficult to define street art, let alone assess its impact, it is clear that many of the messages it communicates resonate with host communities. This paper investigates how street art is defined and promoted in Baltimore, how street art is used in Baltimore neighborhoods to resist oppression, and how Black Lives Matter is influencing street art in Baltimore. -

5Pointz Decision

Case 1:13-cv-05612-FB-RLM Document 172 Filed 02/12/18 Page 1 of 100 PageID #: 4939 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK --------------------------------------------------x JONATHAN COHEN, SANDRA Case No. 13-CV-05612(FB)(RLM) FABARA, STEPHEN EBERT, LUIS LAMBOY, ESTEBAN DEL VALLE, RODRIGO HENTER DE REZENDE, DANIELLE MASTRION, WILLIAM TRAMONTOZZI, JR., THOMAS LUCERO, AKIKO MIYAKAMI, CHRISTIAN CORTES, DUSTIN SPAGNOLA, ALICE MIZRACHI, CARLOS GAME, JAMES ROCCO, STEVEN LEW, FRANCISCO FERNANDEZ, and NICHOLAI KHAN, Plaintiffs, -against- G&M REALTY L.P., 22-50 JACKSON DECISION AVENUE OWNERS, L.P., 22-52 JACKSON AVENUE, LLC, ACD CITIVIEW BUILDINGS, LLC, and GERALD WOLKOFF, Defendants. --------------------------------------------------x MARIA CASTILLO, JAMES COCHRAN, Case No. 15-CV-3230(FB)(RLM) LUIS GOMEZ, BIENBENIDO GUERRA, RICHARD MILLER, KAI NIEDERHAUSEN, CARLO NIEVA, RODNEY RODRIGUEZ, and KENJI TAKABAYASHI, Plaintiffs, -against- Case 1:13-cv-05612-FB-RLM Document 172 Filed 02/12/18 Page 2 of 100 PageID #: 4940 G&M REALTY L.P., 22-50 JACKSON AVENUE OWNERS, L.P., 22-52 JACKSON AVENUE, LLC, ACD CITIVIEW BUILDINGS, LLC, and GERALD WOLKOFF, Defendants. -----------------------------------------------x Appearances: For the Plaintiff For the Defendant ERIC BAUM DAVID G. EBERT ANDREW MILLER MIOKO TAJIKA Eisenberg & Baum LLP Ingram Yuzek Gainen Carroll & 24 Union Square East Bertolotti, LLP New York, NY 10003 250 Park Avenue New York, NY 10177 BLOCK, Senior District Judge: TABLE OF CONTENTS I ..................................................................5 II ..................................................................6 A. The Relevant Statutory Framework . 7 B. The Advisory Jury . 11 C. The Witnesses and Evidentiary Landscape. 13 2 Case 1:13-cv-05612-FB-RLM Document 172 Filed 02/12/18 Page 3 of 100 PageID #: 4941 III ................................................................16 A. -

Mural Mural on the Wall: Revisiting Fair Use of Street Art

UIC REVIEW OF INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LAW MURAL MURAL ON THE WALL: REVISITING FAIR USE OF STREET ART MADYLAN YARC ABSTRACT Mural mural on the wall, what’s the fairest use of them all? Many corporations have taken advantage of public art to promote their own brand. Corporations commission graffiti advertising campaigns because they create a spectacle that gains traction on social media. The battle rages on between the independent artists who wish to protect the exclusive rights over their art, against the corporations who argue that the public art is fair game and digital advertising is fair use of art. The Eastern Market district of Detroit is home to the Murals in the Market Festival. In January 2018, Mercedes Benz obtained a permit from the City of Detroit to photograph its G 500 SUV in specific downtown areas. On January 26, 2018, Mercedes posted six of these photographs on its Instagram account. When Defendant-artists threatened to file suit, Mercedes removed the photos from Instagram as a courtesy. In March 2019, Mercedes filed three declaratory judgment actions against the artists for non-infringement. This Comment will analyze the claims for relief put forth in Mercedes’ complaint and evaluate Defendant-artists’ arguments. Ultimately, this Comment will propose how the court should rule in the pending litigation of MBUSA LLC v. Lewis. Cite as Madylan Yarc, Mural Mural on the Wall: Revisiting Fair Use of Street Art, 19 UIC REV. INTELL. PROP. L. 267 (2020). MURAL MURAL ON THE WALL: REVISITING FAIR USE OF STREET ART MADYLAN YARC I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 267 A. -

App. 1 950 F.3D 155 (2D Cir. 2020) United States Court of Appeals

App. 1 950 F.3d 155 (2d Cir. 2020) United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit Maria CASTILLO, James Cochran, Luis Gomez, Bien- benido Guerra, Richard Miller, Carlo Nieva, Kenji Taka- bayashi, Nicholai Khan, Plaintiffs-Appellees, Jonathan Cohen, Sandra Fabara, Luis Lamboy, Esteban Del Valle, Rodrigo Henter De Rezende, William Tramon- tozzi, Jr., Thomas Lucero, Akiko Miyakami, Christian Cortes, Carlos Game, James Rocco, Steven Lew, Francisco Fernandez, Plaintiffs-Counter- Defendants-Appellees, Kai Niederhause, Rodney Rodriguez, Plaintiffs, v. G&M REALTY L.P., 22-50 Jackson Avenue Owners, L.P., 22-52 Jackson Avenue LLC, ACD Citiview Buildings, LLC, and Gerald Wolkoff, Defendants-Appellants. Nos. 18-498-cv (L), 18-538-cv (CON) August Term 2019 Appeal from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York Nos. 15-cv-3230 (FB) (RLM), 13-cv-5612 (FB) (RLM), Frederic Block, District Judge, Presiding. Argued August 30, 2020 Decided February 20, 2020 Amended February 21, 2020 Attorneys and Law Firms ERIC M. BAUM (Juyoun Han, Eisenberg & Baum, LLP, New York, NY, Christopher J. Robinson, Rottenberg Lipman Rich, P.C., New York, NY, on the brief), Eisenberg & Baum, LLP, New York, NY, for Plaintiffs-Appellees. MEIR FEDER (James M. Gross, on the brief), Jones Day, New York, NY, for Defendants-Appellants. App. 2 Before: PARKER, RAGGI, and LOHIER, Circuit Judges. BARRINGTON D. PARKER, Circuit Judge: Defendants‐Appellants G&M Realty L.P., 22‐50 Jack- son Avenue Owners, L.P., 22‐52 Jackson Avenue LLC, ACD Citiview Buildings, LLC, and Gerald Wolkoff (collec- tively “Wolkoff”) appeal from a judgment of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York (Frederic Block, J.).