Mural Mural on the Wall: Revisiting Fair Use of Street Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Practical Guide to Creating a Mural

A PRACTICAL GUIDE TO CREATING A MURAL 1 WHY CREATE A MURAL? The benefits of murals are plentiful: not only do they beautify and enhance the urban environment, they deter costly tagging, foster community partnerships and pride, and can even boost the local economy. Above all, they’re fun! This guide assists artists, community organizations, business and property owners and arts and heritage organizations by recommending best practices in mural production. The guide is to be used in conjunction with the City of Nelson Murals Policy, which outlines the approval process for murals. An application form must be completed to propose a mural. The City of Nelson’s Cultural Development Commission is also available to offer advice. DEFINITIONS COMMEMORATION: The act of honouring or perpetuating the memory of a person, persons, event, historical period or idea that has been deemed significant. COMMUNITY ART: Public participation and collaboration with professional artists in visual art, dance, music, theatre, literary and/or media arts within a community context and venue. MURAL: A large-scale artwork completed on a surface with the permission of the owner. Media may include paint, ceramic, wood, tile and photography, etc. SIGN: If the primary intent of the work is to convey commercial information, it is a sign. TAGGING: A common type of graffiti is "tagging", which is the writing, painting or "bombing" of an identifiable symbolic character or "tag" that may or may not contain letters. PUBLIC WALLS: A space that belongs to a public organization, i.e. municipal, provincial or federal government. Approval for the mural should be among the first steps undertaken in the planning process. -

Mural Installation Guide City of Frankfort, Kentucky

Mural Installation Guide City of Frankfort, Kentucky This guide is intended to provide answers to basic questions anyone must answer about creating a mural, from how to prepare a wall surface, to what kind of approvals you will need, to appropriate materials to use. The information here has been culled from best practices that have been documented by artists and mural organizations throughout the country. While this guide provides a roadmap, every project will have its own unique circumstances. Anyone taking on a mural project should look for guidance from artists, curators, arts organizations or others who are experienced with the details of mural production. At the end of this publication there is a Resource Guide that provides additional information and tips about where to find help. In This Guide… Part One – Evaluating a Wall I Page 2 Part Two – Approvals and Permissions I Page 4 Part Three – Creating a Design I Page 5 Part Four – Prep Work I Page 6 Part Five – Paint and Supplies I Page 9 Part Six – Maintenance, Repair, Conservation I Page 11 Part Seven – Checklist of Commonly Used Items I Page 12 Part Eight – Resource Guide I Page 13 Part One – Evaluating a Wall The best type of surface to receive paint is one that is a raw, unpainted brick, concrete or stone material that is free of the defects described below. However, keep in mind that the unpainted masonry requires special approval from the Architectural Review Board. Painting unpainted masonry in the historic district is generally not permitted. Wood, metal and other materials that are in new or good condition can also be satisfactory if properly prepared and sealed. -

Anti-Trump Street Art Along the US-Mexico Border" (2019)

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Center for Advanced Research in Global CARGC Papers Communication (CARGC) 8-2019 Dreamers and Donald Trump: Anti-Trump Street Art Along the US- Mexico Border Julia Becker [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/cargc_papers Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Becker, Julia, "Dreamers and Donald Trump: Anti-Trump Street Art Along the US-Mexico Border" (2019). CARGC Papers. 11. https://repository.upenn.edu/cargc_papers/11 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/cargc_papers/11 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dreamers and Donald Trump: Anti-Trump Street Art Along the US-Mexico Border Description What tools are at hand for residents living on the US-Mexico border to respond to mainstream news and presidential-driven narratives about immigrants, immigration, and the border region? How do citizen activists living far from the border contend with President Trump’s promises to “build the wall,” enact immigration bans, and deport the millions of undocumented immigrants living in the United States? How do situated, highly localized pieces of street art engage with new media to become creative and internationally resonant sites of defiance? CARGC Paper 11, “Dreamers and Donald Trump: Anti-Trump Street Art Along the US-Mexico Border,” answers these questions through a textual analysis of street art in the border region. Drawing on her Undergraduate Honors Thesis and fieldwork she conducted at border sites in Texas, California, and Mexico in early 2018, former CARGC Undergraduate Fellow Julia Becker takes stock of the political climate in the US and Mexico, examines Donald Trump’s rhetoric about immigration, and analyzes how street art situated at the border becomes a medium of protest in response to that rhetoric. -

The Evolution of Graffiti Art

Journal of Conscious Evolution Volume 11 Article 1 Issue 11 Issue 11/ 2014 June 2018 From Primitive to Integral: The volutE ion of Graffiti Art White, Ashanti Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/cejournal Part of the Clinical Psychology Commons, Cognition and Perception Commons, Cognitive Psychology Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Liberal Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons, Social Psychology Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, Sociology of Religion Commons, and the Transpersonal Psychology Commons Recommended Citation White, Ashanti (2018) "From Primitive to Integral: The vE olution of Graffiti Art," Journal of Conscious Evolution: Vol. 11 : Iss. 11 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/cejournal/vol11/iss11/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Conscious Evolution by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. : From Primitive to Integral: The Evolution of Graffiti Art Journal of Conscious Evolution Issue 11, 2014 From Primitive to Integral: The Evolution of Graffiti Art Ashanti White California Institute of Integral Studies ABSTRACT Art is about expression. It is neither right nor wrong. It can be beautiful or distorted. It can be influenced by pain or pleasure. It can also be motivated for selfish or selfless reasons. It is expression. Arguably, no artistic movement encompasses this more than graffiti art. -

SAMPLE Portfolio Assessment for ART-395 Urban Mural

SAMPLE Portfolio Assessment for ART-395 Urban Mural Art Note from the Office of Portfolio Assessment Knowledge and background in more “applied” subjects tend to be better suited for portfolio assessment credit because the student’s proof of “doing the work” is viewed as direct evidence of the knowledge. In this portfolio you will see more than a dozen “samples of work” along with several letters of support. In such portfolios those are the two most significant types of necessary evidence to earn credit. ART-395 Urban Mural Art – Table of Contents Course Description and Learning Outcomes page 1 Introduction page 2 Narrative pages 3- 13 Evidence Items • Bibliography page 14 • Letter of support page 15 • Letter of support page 16 • Newspaper Article pages 17 & 18 • Newspaper Article page 19 • Samples of work (17 pages) pages 20 - 36 Summary page 37 Urban Mural Art (ART-395) 3.00 s.h. Course Description The course discusses the history and practice of the contemporary mural movement. The course couples step-by-step analysis of the process of designing with the actual painting of a mural. In addition students will learn to see mural art as a tool for social change. Combining theory with practice, students will design and pain a large outdoor mural in West Philadelphia in collaboration with Philadelphia high school students and local community groups. Learning outcomes: • Develop and understanding of the history and practice of mural design • Analyze the design process • Design and paint a mural • Articulate familiarity with the concept of mural painting as it reflects social change • Demonstrate the ability to collaborate with groups and individuals toward a finished piece of art Introduction My career as an artist predates my career as an educator. -

Defining and Understanding Street Art As It Relates to Racial Justice In

Décor-racial: Defining and Understanding Street Art as it Relates to Racial Justice in Baltimore, Maryland A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Meredith K. Stone August 2017 © 2017 Meredith K. Stone All Rights Reserved 2 This thesis titled Décor-racial: Defining and Understanding Street Art as it Relates to Racial Justice in Baltimore, Maryland by MEREDITH K. STONE has been approved for the Department of Geography and the College of Arts and Sciences by Geoffrey L. Buckley Professor of Geography Robert Frank Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT STONE, MEREDITH K., M.A., August 2017, Geography Décor-racial: Defining and Understanding Street Art as it Relates to Racial Justice in Baltimore, Maryland Director of Thesis: Geoffrey L. Buckley Baltimore gained national attention in the spring of 2015 after Freddie Gray, a young black man, died while in police custody. This event sparked protests in Baltimore and other cities in the U.S. and soon became associated with the Black Lives Matter movement. One way to bring communities together, give voice to disenfranchised residents, and broadcast political and social justice messages is through street art. While it is difficult to define street art, let alone assess its impact, it is clear that many of the messages it communicates resonate with host communities. This paper investigates how street art is defined and promoted in Baltimore, how street art is used in Baltimore neighborhoods to resist oppression, and how Black Lives Matter is influencing street art in Baltimore. -

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice

Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practice PUBLICATIONS COORDINATION: Dinah Berland EDITING & PRODUCTION COORDINATION: Corinne Lightweaver EDITORIAL CONSULTATION: Jo Hill COVER DESIGN: Jackie Gallagher-Lange PRODUCTION & PRINTING: Allen Press, Inc., Lawrence, Kansas SYMPOSIUM ORGANIZERS: Erma Hermens, Art History Institute of the University of Leiden Marja Peek, Central Research Laboratory for Objects of Art and Science, Amsterdam © 1995 by The J. Paul Getty Trust All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-89236-322-3 The Getty Conservation Institute is committed to the preservation of cultural heritage worldwide. The Institute seeks to advance scientiRc knowledge and professional practice and to raise public awareness of conservation. Through research, training, documentation, exchange of information, and ReId projects, the Institute addresses issues related to the conservation of museum objects and archival collections, archaeological monuments and sites, and historic bUildings and cities. The Institute is an operating program of the J. Paul Getty Trust. COVER ILLUSTRATION Gherardo Cibo, "Colchico," folio 17r of Herbarium, ca. 1570. Courtesy of the British Library. FRONTISPIECE Detail from Jan Baptiste Collaert, Color Olivi, 1566-1628. After Johannes Stradanus. Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum-Stichting, Amsterdam. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Historical painting techniques, materials, and studio practice : preprints of a symposium [held at] University of Leiden, the Netherlands, 26-29 June 1995/ edited by Arie Wallert, Erma Hermens, and Marja Peek. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-89236-322-3 (pbk.) 1. Painting-Techniques-Congresses. 2. Artists' materials- -Congresses. 3. Polychromy-Congresses. I. Wallert, Arie, 1950- II. Hermens, Erma, 1958- . III. Peek, Marja, 1961- ND1500.H57 1995 751' .09-dc20 95-9805 CIP Second printing 1996 iv Contents vii Foreword viii Preface 1 Leslie A. -

Brunswick Mural Project 106 Island Drive Saint Simons Island, GA 31522 912-638-8770

Brunswick Mural Project 106 Island Drive Saint Simons Island, GA 31522 912-638-8770 www.glynnvisualarts.org/brunswick-mural-project.html [email protected] INFO FOR ARTISTS Brunswick Mural Project 106 Island Drive Saint Simons Island, GA 31522 912-638-8770 www.glynnvisualarts.org/brunswick-mural-project.html [email protected] Brunswick Mural Committee ROLES AND PROCESS o Serves as the clearing house and coordination point for the Brunswick Mural Project to implement murals o Collects and records names of potential mural artists, building owners and volunteers as a resource bank to execute murals in downtown Brunswick o Identifies and communicates with various community stakeholders including city and county government (elected officials, DDA, Main Street, etc.), businesses, the arts community, the historic preservation board and other interested parties about BMP o Seeks funding and other resources for murals o Glynn Visual Arts as a non-profit community arts center and part of the CoH Arts Sub-Committee acts as repository and distribution point for any monies collected to fund the BMP project Brunswick Mural Project 106 Island Drive Saint Simons Island, GA 31522 912-638-8770 www.glynnvisualarts.org/brunswick-mural-project.html [email protected] ARTIST’S PROCESS 1. Artist submits design ideas and budget to the Mural Committee based on the guidelines included in BMP package 2. Mural Committee matches artist and design with building owner 3. Artist and building owner agree on design, timeline, budget, etc. (contract or MOU may be required) 4. Artist or building owner submits design and completed Certificate of Appropriateness Form to the Historic Preservation Board for approval 5. -

The Writing on the Wall: Graffiti, Street Art, and a New Organic Urban Architecture Name: Isabella Siegel Faculty Adviser: Professor Laura Mcgrane

The Writing on the Wall: Graffiti, Street Art, and a New Organic Urban Architecture Name: Isabella Siegel Faculty Adviser: Professor Laura McGrane In the past half a century, graffiti and street art have grown from roots in Philadelphia to become a worldwide phenomenon. Graffiti is a method of self-expression and defiance that has mutated into new art forms that breach the status quo and gesture toward insurrection. Street art has evolved from such work, as a thriving tradition that works to articulate fears and hopes of a city’s inhabitants on the very buildings they live in. Street art, and graffiti as well, is a complex art form, especially when detangling issues of legality in the U.S. The language of “Organic Architecture” describes the way that the inhabitants of a built space work to determine what fills the empty spaces that remain. Graffiti and street art often constitute the materials with which these inhabitants build. Both genres are methods of expression of a personality, a frustration, or a window into the urban subconscious. These issues speak to Fine Arts and Art History majors, but also to those who study Political Science, History, Economics, Sociology, and Anthropology, and the Growth and Form of Cities. Art history is often used as a bridge into all of these topics, and the study of un-commissioned wall-art is no exception. The insurrectionist political nature of many pieces of street art, and much of graffiti as well, can be studied through the unique lens of someone with a background in political science. -

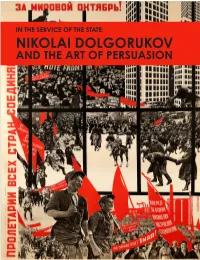

Nikolai Dolgorukov

IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: AGES IM CO U N R T IO E T S Y C E O L L F © T O H C E M N 2020 A E NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV R M R R I E L L B . C AND THE ART OF PERSUASION IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV’ AND THE ART OF PERSUASION NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV’ AND THE ART OF THE STATE: IN THE SERVICE © 2020 Merrill C. Berman Collection IN THE SERVICE OF THE STATE: NIKOLAI DOLGORUKOV AND THE ART OF PERSUASION 1 Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Series Editor, Adrian Sudhalter Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph.D. Content editing by Karen Kettering, Ph.D., Independent Scholar, Seattle, Washington Research assistance by Sofía Granados Dyer, graduate student, Higher School of Economics, Moscow, and Elena Emelyanova, Curator, Rare Books Department, The Russian State Library, Moscow Design, typesetting, production, and photography by Jolie Simpson Copy editing by Madeline Collins Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2020 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted © 2020 the Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Illustrations on pages 39–41 for complete caption information. Cover: Poster: Za Mirovoi Oktiabr’! Proletarii vsekh stran soediniaites’! (Proletariat of the World, Unite Under the Banner of World October!), 1932 Lithograph 57 1/2 x 39 3/8” (146.1 x 100 cm) (p. 103) Acknowledgments We are especially grateful to Sofía Granados Dyer, graduate student at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow, for conducting research in various Russian archives as well as for assisting with the compilation of the documentary sections of this publication: Bibliography, Exhibitions, and Chronology. -

Mural Creation Best Practices

Mural Creation Best Practices Since 2006, Heritage Preservation’s Rescue Public Murals (RPM) initiative has confronted the risks that community murals face by being located in outdoor, public spaces. Murals have been, and are an increasingly, popular public art form that adds vibrancy and vitality to the built landscape. Many communities in the United States, large and small, have mural programs or are actively commissioning murals. Unfortunately, almost every community is also aware of the negative image that a faded, flaking, or vandalized mural creates or the misfortune of an artist’s work that has been unjustly removed or destroyed. While working to ensure the protection and preservation of existing murals, RPM recognizes that many common issues that murals face could have been mitigated with careful planning and preparation. RPM has held conversations and brainstorming sessions with muralists, conservators, art historians, arts administrators, materials scientists, and engineers to document best practices for mural creation. We present these recommendations on this website. Recommendations are not meant to be prescriptive but instead to pose questions and raise issues that should be considered at each stage of creating a mural: planning, wall selection, wall and surface preparation, painting, coating, and maintenance. Each recommendation has been considered both for mural commissioning organizations/agencies and for artists to address their particular needs and concerns. Each section includes links to further reading on the topic. The recommendations on this website assume that a mural that is painted with careful planning and consideration to technique and materials and that receives regular maintenance could have a lifespan of 20-30 years. -

The Unfamiliar in Modern Art: Street Art As a Model

International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change. www.ijicc.net Volume 12, Issue 10, 2020 The Unfamiliar in Modern Art: Street Art as a Model Rana Meery Mizala, Ibtisam Naji Kadhemb*, aBabylon University/ College of Fine Arts/ Department of Design, bBabylon University/ College of Fine Arts/ Department of Plastic Arts, Email: [email protected], b*[email protected] Contemporary art experiences, including street art, are a holistic phenomenon that works to capture everything that surrounds us socially and psychologically, and melts it in a simulation and study of reality as one of the environmental arts that seeks to beautify and preserve the environment. Thus, we always find it be dynamic, as it attracts the changes that afflict civilisation. We even find that the structure of contemporary conceptual art and environmental art has taken a path different from what was previously mentioned in their construction or completion. The later worked to involve the recipient in its construction by raising questions, leaving that to the recipient to mobilise his cognitive abilities to answer the proposals of the contemporary technical text. The true philosophical significance of the work of art is particularly evident in the face of the artist, for what it is in the world (absurdity or strange), and his rebellion only comes by imposing an organised artistic form on reality (Ibrahim, 2010). The criticism of reasonableness in all its varieties, the glorification of life and its elevations, and limitation to the unfamiliar in the implementation of artwork, lasts for hours and days throughout the perspective body to show the viewer that it is real and three- dimensional.