TOCC0380DIGIBKLT.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toccata Classics TOCC0222 Notes

ARTHUR FARWELL: PIANO MUSIC, VOLUME TWO by Lisa Cheryl Thomas When Arthur Farwell, in his late teens and studying electrical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, heard the ‘Unfinished’ Symphony for the first time, he decided that he was going to be not an engineer but a composer. Born in St Paul, Minnesota, on 23 April 1872,1 he was already an accomplished musician: he had learned the violin as a child and often performed in a duo with his pianist elder brother Sidney, in public as well as at home; indeed, he supported himself at college by playing in a sextet. His encounter with Schubert proved detrimental to his engineering studies – he had to take remedial classes in the summer to be able to pass his exams and graduate in 1893 – but his musical awareness grew rapidly, not least though his friendship with an eccentric Boston violin prodigy, Rudolph Rheinwald Gott, and frequent attendances at Boston Symphony Orchestra concerts (as a ‘standee’: he couldn’t afford a seat). Charles Whitefield Chadwick (1854–1931), one of the most prominent of the New England school of composers, offered compositional advice, suggesting, too, that Farwell learn to play the piano as soon as possible. Edward MacDowell (1860–1908), perhaps the leading American Romantic composer, looked over his work from time to time – Farwell’s finances forbade regular study with such an eminent man. But he could afford counterpoint lessons with the organist P Homer Albert Norris (1860–1920), who had studied in Paris with Dubois, Gigout and Guilmant, and piano lessons with Thomas P. -

The American Stravinsky

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY The Style and Aesthetics of Copland’s New American Music, the Early Works, 1921–1938 Gayle Murchison THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS :: ANN ARBOR TO THE MEMORY OF MY MOTHERS :: Beulah McQueen Murchison and Earnestine Arnette Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2012 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ϱ Printed on acid-free paper 2015 2014 2013 2012 4321 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-472-09984-9 Publication of this book was supported by a grant from the H. Earle Johnson Fund of the Society for American Music. “Excellence in all endeavors” “Smile in the face of adversity . and never give up!” Acknowledgments Hoc opus, hic labor est. I stand on the shoulders of those who have come before. Over the past forty years family, friends, professors, teachers, colleagues, eminent scholars, students, and just plain folk have taught me much of what you read in these pages. And the Creator has given me the wherewithal to ex- ecute what is now before you. First, I could not have completed research without the assistance of the staff at various libraries. -

FSU ETD Template

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2018 Rooted in America: The Roy Harris and Henry Cowell Sonatas for Violin and Piano Marianna Cutright Brickle Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC ROOTED IN AMERICA: THE ROY HARRIS AND HENRY COWELL SONATAS FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO By MARIANNA CUTRIGHT BRICKLE A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music 2018 Marianna Brickle defended this treatise on April 2, 2018. The members of the supervisory committee were: Corinne Stillwell Professor Directing Treatise Denise Von Glahn University Representative Shannon Thomas Committee Member Benjamin Sung Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that this treatise has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii To my husband, David Brickle and my parents, Wanda and Edwin Cutright, for their unwavering love and support. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my thanks to all of my committee members: Professor Corinne Stillwell, Dr. Denise Von Glahn, Dr. Benjamin Sung, and Dr. Shannon Thomas for their time, support, and insightful contributions to this project. I extend special thanks to my violin teacher Corinne Stillwell for her pearls of wisdom and her mentorship. Without her guidance, this project would not have been possible. The growth that I have experienced in the past five years, I owe largely to her. Thanks to Denise Von Glahn for her Music in the United States II class, that introduced me to Roy Harris, and helped me grow as a writer. -

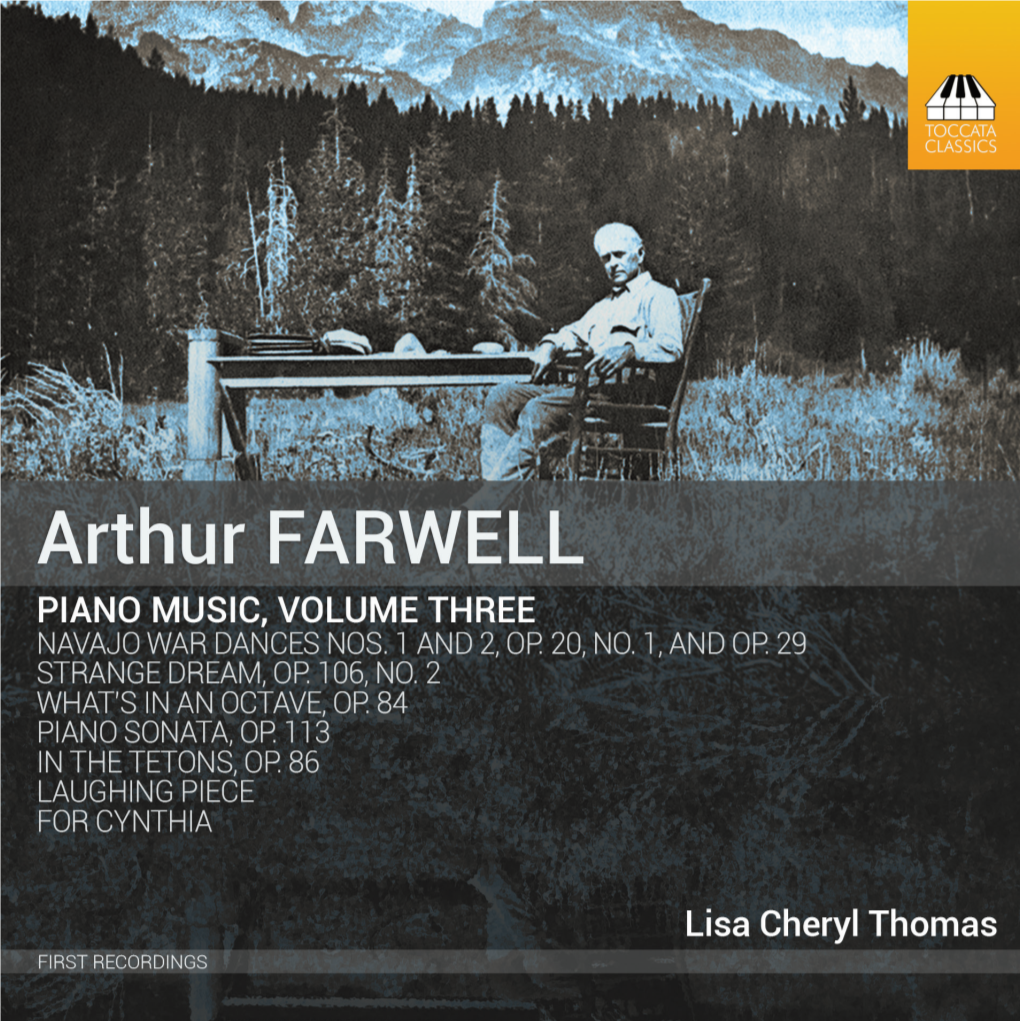

Native American Elements in Piano Repertoire by the Indianist And

NATIVE AMERICAN ELEMENTS IN PIANO REPERTOIRE BY THE INDIANIST AND PRESENT-DAY NATIVE AMERICAN COMPOSERS Lisa Cheryl Thomas, B.M.E., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2010 APPROVED: Adam Wodnicki, Major Professor Steven Friedson, Minor Professor Joseph Banowetz, Committee Member Jesse Eschbach, Chair of the Division of Keyboard Studies Graham Phipps, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Michael Monticino, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Thomas, Lisa Cheryl. Native American Elements in Piano Repertoire by the Indianist and Present-Day Native American Composers. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2010, 78 pp., 25 musical examples, 6 illustrations, references, 66 titles. My paper defines and analyzes the use of Native American elements in classical piano repertoire that has been composed based on Native American tribal melodies, rhythms, and motifs. First, a historical background and survey of scholarly transcriptions of many tribal melodies, in chapter 1, explains the interest generated in American indigenous music by music scholars and composers. Chapter 2 defines and illustrates prominent Native American musical elements. Chapter 3 outlines the timing of seven factors that led to the beginning of a truly American concert idiom, music based on its own indigenous folk material. Chapter 4 analyzes examples of Native American inspired piano repertoire by the “Indianist” composers between 1890-1920 and other composers known primarily as “mainstream” composers. Chapter 5 proves that the interest in Native American elements as compositional material did not die out with the end of the “Indianist” movement around 1920, but has enjoyed a new creative activity in the area called “Classical Native” by current day Native American composers. -

Roy Harris Papers

Roy Harris Papers Processed by the Music Division of the Library of Congress Music Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2010 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/perform.contact Catalog Record: http://lccn.loc.gov/2010562511 Finding aid encoded by Library of Congress Music Division, 2010 Finding aid URL: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/eadmus.mu010029 Latest revision: 2012 April Collection Summary Title: Roy Harris Papers Span Dates: 1893-1998 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1933-1979) Call No.: ML31.H37 Creator: Harris, Roy, 1898-1979 Extent: 6,450 items ; 88 containers ; 40.0 linear feet Language: Material in English Location: Music Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Roy Harris was an American composer. The collection contains materials that document his life and career, including manuscript scores, published and unpublished writings, correspondence, business papers, financial and legal documents, programs, publicity files, photographs, scrapbooks, work files, posters, clippings, and biographical materials. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Boulanger, Nadia--Correspondence. Cage, John--Correspondence. Foss, Lukas, 1922-2009--Correspondence. Harris, Johana--Correspondence. Harris, Johana. Harris, Roy, 1898-1979--Archives. Harris, Roy, 1898-1979--Correspondence. Harris, Roy, 1898-1979--Manuscripts. Harris, Roy, 1898-1979--Photographs. Harris, Roy, 1898-1979. Harris, Roy, 1898-1979. Harris, Roy, 1898-1979. Selections. Ormandy, Eugene, 1899-1985--Correspondence. Persichetti, Vincent, 1915-1987--Correspondence. Starker, Janos--Correspondence. Organizations Pittsburgh International Contemporary Music Festival. -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI DATE: May 16, 2003 I, Nina Perlove , hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in: Flute Performance It is entitled: Ethereal Fluidity: The Late Flute Works of Aaron Copland Approved by: Dr. bruce d. mcclung Dr. Robert Zierolf Dr. Bradley Garner ETHEREAL FLUIDITY: THE LATE FLUTE WORKS OF AARON COPLAND A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS (DMA) in the Division of Performance Studies of the College-Conservatory of Music 2003 by Nina Perlove B.M., University of Michigan, 1995 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 1999 Committee Chair: bruce d. mcclung, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Aaron Copland’s final compositions include two chamber works for flute, the Duo for Flute and Piano (1971) and Threnodies I and II (1971 and 1973), all written as memorial tributes. This study will examine the Duo and Threnodies as examples of the composer’s late style with special attention given to Copland’s tendency to adopt and reinterpret material from outside sources and his desire to be liberated from his own popular style of the 1940s. The Duo, written in memory of flutist William Kincaid, is a representative example of Copland’s 1940s popular style. The piece incorporates jazz, boogie-woogie, ragtime, hymnody, Hebraic chant, medieval music, Russian primitivism, war-like passages, pastoral depictions, folk elements, and Indian exoticisms. The piece also contains a direct borrowing from Copland’s film scores The North Star (1943) and Something Wild (1961). -

UNIVERSITY of CINCINNATI August 2005 Stephanie Bruning Doctor Of

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ The Indian Character Piece for Solo Piano (ca. 1890–1920): A Historical Review of Composers and Their Works D.M.A. Document submitted to the College-Conservatory of Music, University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Piano Performance August 2005 by Stephanie Bruning B.M. Drake University, Des Moines, IA, 1999 M.M. College-Conservatory of Music, University of Cincinnati, 2001 1844 Foxdale Court Crofton, MD 21114 410-721-0272 [email protected] ABSTRACT The Indianist Movement is a title many music historians use to define the surge of compositions related to or based on the music of Native Americans that took place from around 1890 to 1920. Hundreds of compositions written during this time incorporated various aspects of Indian folklore and music into Western art music. This movement resulted from many factors in our nation’s political and social history as well as a quest for a compositional voice that was uniquely American. At the same time, a wave of ethnologists began researching and studying Native Americans in an effort to document their culture. In music, the character piece was a very successful genre for composers to express themselves. It became a natural genre for composers of the Indianist Movement to explore for portraying musical themes and folklore of Native-American tribes. -

A New American Development in Music: Some Characteristic Features Extending from the Legacy of Charles Ives

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1976 A New American Development in Music: Some Characteristic Features Extending From the Legacy of Charles Ives. Joan Kunselman Cordes Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Cordes, Joan Kunselman, "A New American Development in Music: Some Characteristic Features Extending From the Legacy of Charles Ives." (1976). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2955. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2955 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. -

Toccata Classics TOCC 0126 Notes

ARTHUR FARWELL: PIANO MUSIC, VOLUME ONE by Lisa Cheryl Thomas ‘he evil that men do lives ater them’, says Mark Antony in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar; ‘he good is ot interred with their bones.’ Luckily, that isn’t true of composers: Schubert’s bones had been in the ground for over six decades when the young Arthur Farwell, studying electrical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, heard the ‘Uninished’ Symphony for the irst time and decided that he was going to be not an engineer but a composer. Farwell, born in St Paul, Minnesota, on 23 March 1872,1 was already an accomplished musician: he had learned the violin as a child and oten performed in a duo with his pianist elder brother Sidney, in public as well as at home; indeed, he supported himself at college by playing in a sextet. His encounter with Schubert proved detrimental to his engineering studies – he had to take remedial classes in the summer to be able to pass his exams and graduated in 1893 – but his musical awareness expanded rapidly, not least through his friendship with an eccentric Boston violin prodigy, Rudolph Rheinwald Gott, and frequent attendance at Boston Symphony Orchestra concerts (as P a ‘standee’: he couldn’t aford a seat). Charles Whiteield Chadwick (1854–1931), one of the most prominent of the New England school of composers, ofered compositional advice, suggesting, too, that Farwell learn to play the piano as soon as possible. Edward MacDowell (1860–1908), perhaps the leading American Romantic composer of the time, looked over his work from time to time – Farwell’s inances forbade regular study with such an eminent igure, but he could aford counterpoint lessons with the organist Homer Albert Norris (1860–1920), who had studied in Paris with Dubois, Gigout and Guilmant, and piano lessons with homas P. -

The East in the Works of Charles Griffes A

2020 ВЕСТНИК САНКТ-ПЕТЕРБУРГСКОГО УНИВЕРСИТЕТА Т. 10. Вып. 1 ИСКУССТВОВЕДЕНИЕ МУЗЫКА UDC 78.03 The East in the Works of Charles Griffes A. E. Krom Nizhny Novgorod State Academy of Music named after M. Glinka, 40, Piskunova str., Nizhny Novgorod, 603005, Russian Federation For citation: Krom, Anna. “The East in the Works of Charles Griffes”. Vestnik of Saint Petersburg University. Arts 10, no. 1 (2020): 3–16. https://doi.org/10.21638/spbu15.2020.101 The article is devoted to the oriental compositions of the American composer Charles Griffes (1884–1920), created in the 1910s. These include the symphonic poem “The Pleasure-Dome of Kubla Khan” (1912–1917), the vocal cycle “Five Poems of Ancient China and Japan” for voice and piano (1916–1917), and the Japanese pantomime “Sho-Jo” (1917). Significant creative con- tacts (Eva Gauthier, A. Coomaraswamy, E. Bloch, A. Bolm, M. Ito), extensive reading, fascination with folklore, poetry, painting, and philosophy of Asian countries led to the formation of his own method of working with oriental materials. The composer saw prospects for the interaction of Western and Eastern music in his address to the archaic, to the stylization of ancient folklore. An example is the music for the pantomime “Sho-Jo” and the cycle “Five Poems of Ancient Chi- na and Japan.” Natural modes (pentatonic modes), organ points, ascetic quarto-quinto-second verticals, spatial sound, and rhythmic ostinato allow us to draw parallels with new folkloristics, in particular, with the works of I. F. Stravinsky. In the symphonic poem “The Pleasure-Dome of Kubla Khan,” the European influences at the forefront are associated with the study of the “Russian” East (first of all the writings of N. -

LINER NOTES Recorded Anthology of American Music, Inc

BEACH, FOOTE, FARWELL, OREM New World Records 80542 The "Indianist" Movement in American Music by Gilbert Chase The "Indianist" movement in American musical composition that flourished from the 1880s to the 1920s had its antecedents in nineteenth-century Romanticism, with its cult of “the noble savage" nourished by such writers as Chateaubriand, James Fenimore Cooper, and Longfellow, whose Hiawatha was like a magnet for many musicians. On the stage, the famous actor Edwin Forrest starred in the drama Metamora (1828) as "the noble Indian chief," who leads his warriors in a desperate struggle for freedom—"Our Lands! Our Nation's Freedom!—Or the Grave." Romantic writers tended to identify the Indian with the grandeur of Nature. Chateaubriand, a Frenchman, in his novel of the "noble savage" Atala gushed on "the soul's delight to lose itself amidst the wild sublimities of Nature." Such writers often lost their heads but seldom risked their lives. The American wilderness, viewed as untamed, primitive, exotic, lured not only explorers and adventurers hut also scientists, artists, poets, novelists—and at least one musician who came to know at first hand "the magnificent wilds of Kentucky" about which Chateaubriand rhapsodized. This venturesome musician was Anthony Philip Heinrich (1781–1861), a native of Bohemia who emigrated to America in 1810. From 1817 to 1823 he lived in and around Lexington, Kentucky, calling himself "the Wildwood Troubador." According to a contemporary account: Heinrich passed several years of his life among the Indians that once inhabited Kentucky, and many of his compositions refer to these aboriginal companions. He is a species of musical Catlin, painting his dusky friends on the music staff instead of on the canvas, and composing laments, symphonies, dirges, and on the most intensely Indian subjects. -

WILLIAM PARKER New World Records 80463 an Old Song Resung

WILLIAM PARKER New World Records 80463 An Old Song Resung During the last third of the nineteenth century, several thoroughly trained composers from the Northeast began to fashion an American music deriving from German stylistic principles, impeccably crafted and with considerable aesthetic substance--men such as John Knowles Paine, Arthur Foote, George Chadwick, Horatio Parker, and Edward MacDowell. In addition, several of Chadwick's and one of MacDowell's compositions were given an identifiably American flavor, however diluted: Chadwick's Yankee-oriented Second Symphony in B-flat (1886), Fourth String Quartet in E-minor (1896), and Symphonic Sketches (1895-1904); and MacDowell's Second Suite (Indian) in E-minor (1891-1895). Despite the qualitative excellence of their compositions, a nagging question persisted among contemporary writers about the music: Was it American? Before the time of these five musicians, a fascinating New Orleans pianist and composer, Louis Moreau Gottschalk (1829-1869), had already been active and acclaimed. Gottschalk's father was born in London and his mother was of French descent. After training in Paris, he explored the use of the vernacular music of Latin America and the United States in his piano music. He died relatively young, however, leaving behind a memory more of the irresistibly charming pianist than of an innovative creator. Then from 1892 to 1895, the Czech nationalist composer Antonin Dvorák resided in New York, and became attracted to African-American and Amerindian music. He created a few works that integrated these New World sounds with his own Central European manner, especially in the Ninth Symphony (From the New World), Twelfth String Quartet (American), and String Quintet in E-flat.