The East in the Works of Charles Griffes A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selected Intermediate-Level Solo Piano Music Of

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Selected intermediate-level solo piano music of Enrique Granados: a pedagogical analysis Harumi Kurihara Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Kurihara, Harumi, "Selected intermediate-level solo piano music of Enrique Granados: a pedagogical analysis" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3242. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3242 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. SELECTED INTERMEDIATE-LEVEL SOLO PIANO MUSIC OF ENRIQUE GRANADOS: A PEDAGOGICAL ANALYSIS A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Harumi Kurihara B.M., Loyola University, New Orleans, 1993 M.M.,University of New Orleans, 1997 August, 2005 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my sincere appreciation to my major professor, Professor Victoria Johnson for her expert advice, patience, and commitment to my monograph. Without her help, I would not have been able to complete this monograph. I am also grateful to my committee members, Professors Jennifer Hayghe, Michael Gurt, and Jeffrey Perry for their interest and professional guidance in making this monograph possible. I must also recognize the continued encouragement and support of Professor Constance Carroll who provided me with exceptional piano instruction throughout my doctoral studies. -

IGUSTAV MAHLER Ik STUDY of HIS PERSONALITY 6 WORK

IGUSTAV MAHLER Ik STUDY OF HIS PERSONALITY 6 WORK PAUL STEFAN ML 41O M23S831 c.2 MUSI UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO Presented to the FACULTY OF Music LIBRARY by Estate of Robert A. Fenn GUSTAV MAHLER A Study of His Personality and tf^ork BY PAUL STEFAN TRANSLATED FROM THE GERMAN EY T. E. CLARK NEW YORK : G. SCHIRMER COPYRIGHT, 1913, BY G. SCHIRMER 24189 To OSKAR FRIED WHOSE GREAT PERFORMANCES OF MAHLER'S WORKS ARE SHINING POINTS IN BERLIN'S MUSICAL LIFE, AND ITS MUSICIANS' MOST SPLENDID REMEMBRANCES, THIS TRANSLATION IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED BERLIN, Summer of 1912. TRANSLATOR'S PREFACE The present translation was undertaken by the writer some two years ago, on the appearance of the first German edition. Oskar Fried had made known to us in Berlin the overwhelming beauty of Mahler's music, and it was intended that the book should pave the way for Mahler in England. From his appearance there, we hoped that his genius as man and musi- cian would be recognised, and also that his example would put an end to the intolerable existing chaos in reproductive music- making, wherein every quack may succeed who is unscrupulous enough and wealthy enough to hold out until he becomes "popular." The English musician's prayer was: "God pre- serve Mozart and Beethoven until the right man comes," and this man would have been Mahler. Then came Mahler's death with such appalling suddenness for our youthful enthusiasm. Since that tragedy, "young" musicians suddenly find themselves a generation older, if only for the reason that the responsibility of continuing Mah- ler's ideals now rests upon their shoulders in dead earnest. -

Tchaikovsky's Romeo and Juliet

Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet: A Schleiermacherian Interpretation Emer Nestor This article will discuss the application of Friedrich Daniel Ernst Schleiermacher’s (1768-1834) hermeneutical methods to a general reading of Tchaikovsky’s fantasy-overture, Romeo and Juliet. The German philosopher gave a lecture series on hermeneutics at the University of Berlin in 1819, and from his research on the subject he invariably redefined this field of philosophical thinking. The central elements of his ‘whole and parts’ theory will be discussed as an alternative mode of investigative music analysis. Richard E. Palmer presents six modern definitions of hermeneutics as follows: 1) The theory of biblical exegesis 2) General philological methodology 3) The science of all linguistic understanding 4) The methodological foundation of Geisteswissenschaften 5) Phenomenology of existence and of existential understanding 6) The systems of interpretation, both recollective and iconoclastic used by man to reach the meaning behind myths and symbols.1 The term ‘hermeneutics’ is a word which is prominent in theological, philosophical and literary circles but relatively new to the discipline of musicology.2 Ian Bent asserts that it ‘came to prominence in writing about music implicitly in the nineteenth century and explicitly in the early twentieth century’.3 He remarks that no author in the nineteenth century 1 Richard E. Palmer.: Hermeneutics: Interpretation Theory in Schleiermacher, Dilthey, Heidegger and Gadamer (Evanstown: Northwestern University Press, 1969), 3 3 - Hereafter referred to as Palmer: Hermeneutics. 2 For a more in-depth discussion of hermeneutics see Kurt Mueller-Vollmer: The Hermeneutics Reader: Texts of the German Tradition from the Enlightenment to the Present (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1986). -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Music as Representational Art Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1vv9t9pz Author Walker, Daniel Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Volume I Music as Representational Art Volume II Awakening A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Daniel Walker 2014 © Copyright by Daniel Walker 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Volume I Music as Representational Art Volume II Awakening by Daniel Walker Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Ian Krouse, Chair There are two volumes to this dissertation; the first is a monograph, and the second is a musical composition, both of which are described below. Volume I Music is a language that can be used to express a vast range of ideas and emotions. It has been part of the human experience since before recorded history, and has established a unique place in our consciousness, and in our hearts by expressing that which words alone cannot express. ii My individual interest in the musical language is its use in telling stories, and in particular in the form of composition referred to as program music; music that tells a story on its own without the aid of images, dance or text. The topic of this dissertation follows this line of interest with specific focus on the compositional techniques and creative approach that divide program music across a representational spectrum from literal to abstract. -

COCKEREL Education Guide DRAFT

VICTOR DeRENZI, Artistic Director RICHARD RUSSELL, Executive Director Exploration in Opera Teacher Resource Guide The Golden Cockerel By Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov Table of Contents The Opera The Cast ...................................................................................................... 2 The Story ...................................................................................................... 3-4 The Composer ............................................................................................. 5-6 Listening and Viewing .................................................................................. 7 Behind the Scenes Timeline ....................................................................................................... 8-9 The Russian Five .......................................................................................... 10 Satire and Irony ........................................................................................... 11 The Inspiration .............................................................................................. 12-13 Costume Design ........................................................................................... 14 Scenic Design ............................................................................................... 15 Q&A with the Queen of Shemakha ............................................................. 16-17 In The News In The News, 1924 ........................................................................................ 18-19 -

Brahms and the Changing Piano

The Aesthetics of Textural Ambiguity: Brahms and the Changing Piano Augustus Arnone The thought beneath so slight a film Is more distinctly seen As laces just reveal the surge Or Mists the Apennine -Emily Dickinson Introduction In recent years, a number of performance practice scholars writing on Brahms's piano music have commented on the prominence of low-lying melodic lines, thickly-written accompaniments, and often dense saturation of the lower register.! For such writers these textural features constitute proof that Brahms could not have intended performance on the modern piano. Firms such as Steinway, Bechstein, and Chickering were manufacturing pianos by the early 1860s, roughly the midpoint of Brahms's life, that already exhibited most of the important design innovations that distinguish modern pianos from earlier ones, and these firms enjoyed enormous success across Europe.2 Performance practice scholars have argued that the increased power and sustain of these pianos create irreparable problems of balance and clarity in much of Brahms's music, implying that he was writing for the lighter and more transparent instruments that predate the modern piano, many of which were still manufactured up until the end of the century. The view that low-lying melodies and densely packed textures in the lower register present an undesirable muddiness on the modern piano was already being elaborated towards the end of the nineteenth century. During the last decades of Brahms's life, several treatises appeared elucidating the fundamental principles of what they proclaimed to be the "modern school of pianoforte playing." Three treatises in particular, those by Hans Schmitt (1893), Aleksandr Nikitich Bukhovtsev (1897), and Adolph Christiani (c. -

The Eclectic Careers of Eva and Juliette Gauthier Anita Slominska

Interpreting success and failure: The eclectic careers of Eva and Juliette Gauthier Anita Slominska Art History and Communication Studies McGill University, Montreal April 2009 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ©2009 Anita Slominska Abstract My dissertation explores the eclectic singing careers of sisters Eva and Juliette Gauthier. Born in Ottawa, Eva and Juliettte were aided in their musical aspirations by the patronage of Prime Minister Wilfred Laurier and his wife Lady Zoë. They both received classical vocal training in Europe. Eva spent four years in Java. She studied the local music, which later became incorporated into her concert repertoire in North America. She went on to become a leading interpreter of modern art song. Juliette became a performer of Canadian folk music in Canada, the United States and Europe, aiming to reproduce folk music “realistically” in a concert setting. My dissertation is the result of examining archival materials pertaining to their careers, combined with research into the various social and cultural worlds they traversed. Eva and Juliette’s careers are revealing of a period of transition in the arts and in social experience more generally. These transitions are related to the exploitation of non-Western people, uses of the “folk,” and the emergence of a cultural marketplace that was defined by a mixture of highbrow institutions and mass culture industries. My methodology draws from the sociology of art and cultural history, transposing Eva and Juliette Gauthier against the backdrop of the social, cultural and economic conditions that shaped their career trajectories and made them possible. -

Bowen Abstract

The Rise and Fall of the Bass Clarinet in A Keith Bowen The bass clarinet in A was introduced by Wagner in Lohengrin in 1848. It was used up to 1990 in about sixty works by over twenty composers, including the Ring cycle, five Mahler symphonies and Rosenkavalier. But it last appeared in Messiaen’s Turangalîla-Symphonie (1948, revised 1990), and the instrument is generally regarded as obsolete.1 Several publications discuss the bass clarinet, notably Rice (2009). However, only Leeson2 and Joppig3 seriously discuss the ‘A’ instrument. Leeson suggests possibilities for its popularity: compatibility with the tonality of the soprano clarinets, the extra semitone at the bottom of the range and the sonority of the instrument. For its disappearance he posits the extension of range of the B¨ bass, and the convenience of having only one instrument. He suggests that its history is more likely to be found in the German than in the French bass clarinet tradition. Joppig examines one aspect of this tradition: Mahler’s use of the clarinet family. The first successful4 bass clarinet was the bassoon form, invented by Grenser in 1793 and made in quantity for almost a century. These instruments descended to at least C and had sufficient range for all parts for the bass clarinet in A.5 They were made in B¨ and C, but no examples in A are known so far. Their main use was in wind bands to provide a more powerful bass than the bassoon.6 For orchestral music, they were perceived to be only partially successful as bass for the clarinet family because of their different principle of construction.7 The modern form was invented by Desfontenelles in 1807 and improved by Buffet (1833) and Adolphe Sax (1838). -

The Inextricable Link Between Literature and Music in 19Th

COMPOSERS AS STORYTELLERS: THE INEXTRICABLE LINK BETWEEN LITERATURE AND MUSIC IN 19TH CENTURY RUSSIA A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Ashley Shank December 2010 COMPOSERS AS STORYTELLERS: THE INEXTRICABLE LINK BETWEEN LITERATURE AND MUSIC IN 19TH CENTURY RUSSIA Ashley Shank Thesis Approved: Accepted: _______________________________ _______________________________ Advisor Interim Dean of the College Dr. Brooks Toliver Dr. Dudley Turner _______________________________ _______________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Mr. George Pope Dr. George R. Newkome _______________________________ _______________________________ School Director Date Dr. William Guegold ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. OVERVIEW OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF SECULAR ART MUSIC IN RUSSIA……..………………………………………………..……………….1 Introduction……………………..…………………………………………………1 The Introduction of Secular High Art………………………………………..……3 Nicholas I and the Rise of the Noble Dilettantes…………………..………….....10 The Rise of the Russian School and Musical Professionalism……..……………19 Nationalism…………………………..………………………………………..…23 Arts Policies and Censorship………………………..…………………………...25 II. MUSIC AND LITERATURE AS A CULTURAL DUET………………..…32 Cross-Pollination……………………………………………………………...…32 The Russian Soul in Literature and Music………………..……………………...38 Music in Poetry: Sound and Form…………………………..……………...……44 III. STORIES IN MUSIC…………………………………………………… ….51 iii Opera……………………………………………………………………………..57 -

Symphony and Symphonic Thinking in Polish Music After 1956 Beata

Symphony and symphonic thinking in Polish music after 1956 Beata Boleslawska-Lewandowska UMI Number: U584419 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U584419 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Declaration This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signedf.............................................................................. (candidate) fa u e 2 o o f Date: Statement 1 This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed:.*............................................................................. (candidate) 23> Date: Statement 2 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed: ............................................................................. (candidate) J S liiwc Date:................................................................................. ABSTRACT This thesis aims to contribute to the exploration and understanding of the development of the symphony and symphonic thinking in Polish music in the second half of the twentieth century. -

Nikolai Tcherepnin UNDER the CANOPY of MY LIFE Artistic, Creative, Musical Pedagogy, Public and Private

Nikolai Tcherepnin UNDER THE CANOPY OF MY LIFE Artistic, creative, musical pedagogy, public and private Translated by John Ranck But1 you are getting old, pick Flowers, growing on the graves And with them renew your heart. Nekrasov2 And ethereally brightening-within-me Beloved shadows arose in the Argentine mist Balmont3 The Tcherepnins are from the vicinity of Izborsk, an ancient Russian town in the Pskov province. If I remember correctly, my aged aunts lived on an estate there which had been passed down to them by their fathers and grandfathers. Our lineage is not of the old aristocracy, and judging by excerpts from the book of Records of the Nobility of the Pskov province, the first mention of the family appears only in the early 19th century. I was born on May 3, 1873 in St. Petersburg. My father, a doctor, was lively and very gifted. His large practice drew from all social strata and included literary luminaries with whom he collaborated as medical consultant for the gazette, “The Voice” that was published by Kraevsky.4 Some of the leading writers and poets of the day were among its editors. It was my father’s sorrowful duty to serve as Dostoevsky’s doctor during the writer’s last illness. Social activities also played a large role in my father’s life. He was an active participant in various medical societies and frequently served as chairman. He also counted among his patients several leading musical and theatrical figures. My father was introduced to the “Mussorgsky cult” at the hospitable “Tuesdays” that were hosted by his colleague, Dr. -

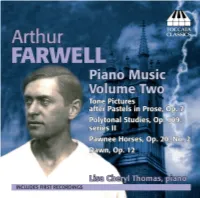

Toccata Classics TOCC0222 Notes

ARTHUR FARWELL: PIANO MUSIC, VOLUME TWO by Lisa Cheryl Thomas When Arthur Farwell, in his late teens and studying electrical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, heard the ‘Unfinished’ Symphony for the first time, he decided that he was going to be not an engineer but a composer. Born in St Paul, Minnesota, on 23 April 1872,1 he was already an accomplished musician: he had learned the violin as a child and often performed in a duo with his pianist elder brother Sidney, in public as well as at home; indeed, he supported himself at college by playing in a sextet. His encounter with Schubert proved detrimental to his engineering studies – he had to take remedial classes in the summer to be able to pass his exams and graduate in 1893 – but his musical awareness grew rapidly, not least though his friendship with an eccentric Boston violin prodigy, Rudolph Rheinwald Gott, and frequent attendances at Boston Symphony Orchestra concerts (as a ‘standee’: he couldn’t afford a seat). Charles Whitefield Chadwick (1854–1931), one of the most prominent of the New England school of composers, offered compositional advice, suggesting, too, that Farwell learn to play the piano as soon as possible. Edward MacDowell (1860–1908), perhaps the leading American Romantic composer, looked over his work from time to time – Farwell’s finances forbade regular study with such an eminent man. But he could afford counterpoint lessons with the organist P Homer Albert Norris (1860–1920), who had studied in Paris with Dubois, Gigout and Guilmant, and piano lessons with Thomas P.