Symphony and Symphonic Thinking in Polish Music After 1956 Beata

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

20Th-Century Repertory

Mikrokosmos List 665. - 2 - January 2021 ....20TH-CENTURY REPERTORY 1 Adam, Claus: Vcl Con/ Barber: Die Natali - Kates vcl, cond.Mester 1975 S LOUISVILLE LS 745 A 12 2 Adams, John: Shaker Loops, Phrygian Gates - McCray pno, Ridge SQ, etc 1979 S 1750 ARCH S 1784 A 10 3 Baaren, Kees van: Musica per orchestra; Musica per organo/Brons, Carel: Prisms DONEMUS 72732 A 8 (organ) - Wolff organ, cond.Haitink , (score enclosed) S 4 Badings: Con for Orch/H.Andriessen: Kuhnau Var/Brahms: Sym 4 - Regionaal 2 x REGIONAAL JBTG A 15 Jeugd Orkest, cond.Sevenhuijsen live, 1982, 1984 S 7118401 5 Bax: Sym 3, The Happy Forest - London SO, cond.Downes (UK) (p.1969) S RCA SB 6806 A 8 6 Bernstein, Elmer: Summer and Smoke (sound track) - cond.comp S ENTRACTE ERS 6519 A 8 7 Bernstein, Elmer: The Magnificent Seven - cond.comp S LIBERTY EG 260581 A 8 8 Bernstein, Elmer: To Kill a Mockingbird (film music) - Royal PO, cond.E.Bernstein FILMMUSIC FMC 7 A 25 1976 S 9 Bernstein, Elmer: Walk on the Wild Side (soundtrack) - cond.comp S CHOREO AS 4 A 8 10 Bernstein, Ermler: Paris Swings (soundtrack) S CAPITOL ST 1288 A 8 11 Bolling: The Awakening (soundtrack) S ENTRACTE ERS 6520 A 8 12 Bretan, Nicolae: Ady Lieder - comp.pno & vocal (one song only), L.Konya bar, MHS 3779 A 8 F.Weiss, M.Berkofsky pno S 13 Castelnuovo-Tedesco: The Well-Tempered Guitars - Batendo Guitar Duo (gatefold) 2 x ETCETERA ETC 2009 A 15 (p.1986) S 14 Casterede, Jacques: Suite a danser - Hewitt Orch (light music) 10" DISCOPHILE SD 5 B+ 10 15 Dandara, Liviu: Timpul Suspendat, Affectus, Quadriforium III -

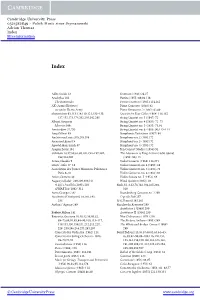

Polish Music Since Szymanowski Adrian Thomas Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 0521582849 - Polish Music since Szymanowski Adrian Thomas Index More information Index Adler,Guido 12 Overture (1943) 26,27 Aeschylus 183 Partita (1955) 69,94,116 The Eumenides Pensieri notturni (1961) 114,162 AK (Armia Krajowa) Piano Concerto (1949) 62 see under Home Army Piano Sonata no. 2 (1952) 62,69 aleatoricism 93,113,114,119,121,132–133, Quartet for Four Cellos (1964) 116,162 137,152,173,176,202,205,242,295 String Quartet no. 3 (1947) 72 Allegri,Gregorio String Quartet no. 4 (1951) 72–73 Miserere 306 String Quartet no. 5 (1955) 73,94 Amsterdam 32,293 String Quartet no. 6 (1960) 90,113–114 Amy,Gilbert 89 Symphonic Variations (1957) 94 Andriessen,Louis 205,265,308 Symphony no. 2 (1951) 72 Ansermet,Ernest 9 Symphony no. 3 (1952) 72 Apostel,Hans Erich 87 Symphony no. 4 (1953) 72 Aragon,Louis 184 Ten Concert Studies (1956) 94 archaism 10,57,60,61,68,191,194–197,294, The Adventure of King Arthur (radio opera) 299,304,305 (1959) 90,113 Arrau,Claudio 9 Viola Concerto (1968) 116,271 artists’ cafés 17–18 Violin Concerto no. 4 (1951) 69 Association des Jeunes Musiciens Polonais a` Violin Concerto no. 5 (1954) 72 Paris 9–10 Violin Concerto no. 6 (1957) 94 Attlee,Clement 40 Violin Sonata no. 5 (1951) 69 Augustyn,Rafal 289,290,300,311 Wind Quintet (1932) 10 A Life’s Parallels (1983) 293 Bach,J.S. 8,32,78,182,194,265,294, SPHAE.RA (1992) 311 319 Auric,Georges 7,87 Brandenburg Concerto no. -

Zbornik Radova | Književnost Knjiga 2 Knjiga Bosanskohercegovački Slavistički Kongres Zbornik Radova (Knjiga 2)

Bosanskohercegovački slavistički kongres II ZBORNIK RADOVA | KNJIŽEVNOST KNJIGA 2 KNJIGA BOSANSKOHERCEGOVAČKI SLAVISTIČKI KONGRES ZBORNIK RADOVA (KNJIGA 2) © Slavistički komitet; prvo izdanje, 2019. Sva prava pridržana. Nijedan dio ove publikacije ne smije se umnožavati na bilo koji način ili javno reproducirati bez prethodnog dopuštenja izdavača. Izdavač Slavistički komitet, Sarajevo Filozofski fakultet u Sarajevu, F. Račkog 1, Sarajevo, BiH tel. (+387) 33 253 170 e-mail [email protected] www.slavistickikomitet.ba REDAKCIJA Ifeta Čirić-Fazlija, Dijana Hadžizukić, Adijata Ibrišimović-Šabić, Andrea Lešić, Lejla Mulalić, Edina Murtić Glavni urednik Senahid Halilović Urednica Adijata Ibrišimović-Šabić ISSN 2303-4106 ZBORNIK RADOVA | KNJIŽEVNOST Bosanskohercegovački slavistički kongres II Zbornik radova (knjiga 2) Sarajevo, 2019. KNJIGA 2 KNJIGA Objavljivanje ove knjige finansijski je podržalo Federalno ministarstvo obrazovanja i nauke. Bosanskohercegovački slavistički kongres II: Zbornik radova (knjiga 2) 5 SADRŽAJ Predgovor . 9 Adijata Ibrišimović-Šabić: Pod/sjećanja: Prvi bosanskohercegovački slavistički kongres (Predstavljanje Zbornika radova iz književnosti) . 11 I. Književni folklor i stara književnost............................... 15 Masha Belyavski-Frank: Flowers, Fruit, and Food: Symbolism in Bosnian and Macedonian Love Songs and Wedding Songs . 17 Dolores Grmača: Mali Nauk krstjanski fra Matije Divkovića . 40 II. Književnosti narodā BiH i (južno)slavenske književnosti u komparativnoj, interliterarnoj i interkulturalnoj -

Cds by Composer/Performer

CPCC MUSIC LIBRARY COMPACT DISCS Updated May 2007 Abercrombie, John (Furs on Ice and 9 other selections) guitar, bass, & synthesizer 1033 Academy for Ancient Music Berlin Works of Telemann, Blavet Geminiani 1226 Adams, John Short Ride, Chairman Dances, Harmonium (Andriessen) 876, 876A Adventures of Baron Munchausen (music composed and conducted by Michael Kamen) 1244 Adderley, Cannonball Somethin’ Else (Autumn Leaves; Love For Sale; Somethin’ Else; One for Daddy-O; Dancing in the Dark; Alison’s Uncle 1538 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Jazz Improvisation (vol 1) 1270 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: The II-V7-1 Progression (vol 3) 1271 Aerosmith Get a Grip 1402 Airs d’Operettes Misc. arias (Barbara Hendricks; Philharmonia Orch./Foster) 928 Airwaves: Heritage of America Band, U.S. Air Force/Captain Larry H. Lang, cond. 1698 Albeniz, Echoes of Spain: Suite Espanola, Op.47 and misc. pieces (John Williams, guitar) 962 Albinoni, Tomaso (also Pachelbel, Vivaldi, Bach, Purcell) 1212 Albinoni, Tomaso Adagio in G Minor (also Pachelbel: Canon; Zipoli: Elevazione for Cello, Oboe; Gluck: Dance of the Furies, Dance of the Blessed Spirits, Interlude; Boyce: Symphony No. 4 in F Major; Purcell: The Indian Queen- Trumpet Overture)(Consort of London; R,Clark) 1569 Albinoni, Tomaso Concerto Pour 2 Trompettes in C; Concerto in C (Lionel Andre, trumpet) (also works by Tartini; Vivaldi; Maurice André, trumpet) 1520 Alderete, Ignacio: Harpe indienne et orgue 1019 Aloft: Heritage of America Band (United States Air Force/Captain Larry H. -

Graå»Yna Bacewicz and Her Violin Compositions

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 Gra#yna Bacewicz and Her Violin Compositions: From a Perspective of Music Performance Hui-Yun (Yi-Chen) Chung Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC GRAŻYNA BACEWICZ AND HER VIOLIN COMPOSITIONS- FROM A PERSPECTIVE OF MUSIC PERFORMANCE By HUI-YUN (YI-CHEN) CHUNG A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2011 Hui‐Yun Chung defended this treatise on November 3, 2011. The members of the supervisory committee were: Eliot Chapo Professor Directing Treatise James Mathes University Representative Melanie Punter Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above‐named committee members, and certifies that the treatise has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii To my beloved family iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my deep gratitude and thanks to Professor Eliot Chapo for his support and guidance in the completion of my treatise. I also thank my committee members, Dr. James Mathes and Professor Melanie Punter, for their time, support and collective wisdom throughout this process. I would like to give special thanks to my previous violin teacher, Andrzej Grabiec, for his encouragement and inspiration. I wish to acknowledge my great debt to Dr. John Ho and Lucy Ho, whose kindly support plays a crucial role in my graduate study. I am grateful to Shih‐Ni Sun and Ming‐Shiow Huang for their warm‐hearted help. -

Penderecki Has Enjoyed an International Reputation for Music That Blends Direct, Emotional Appeal with Contemporary Compositional Techniques

CMYK NAXOS NAXOS Since 1966, with the composition of the St Luke Passion (Naxos 8.557149), Penderecki has enjoyed an international reputation for music that blends direct, emotional appeal with contemporary compositional techniques. The neo-Romantic choral work, Te Deum, was inspired by the anointing of Karol Wojtyla as the first Polish Pope in 1978. Although Penderecki’s recent choral works have tended to be similarly monumental in scale, he has written several of a more compact DDD PENDERECKI: nature, such as Hymne an den heiligen Daniel, whose opening ranks as one of the composer’s most PENDERECKI: affecting. This disc closes with two works for strings: the experimental Polymorphia from 1961, 8.557980 and the expressive Chaconne, written in 2005 as a tribute to the late Pope John Paul II. Krzysztof Playing Time PENDERECKI 67:06 (b. 1933) Te Deum Te Deum Te Te Deum (1979-80)* 36:46 Deum Te 1 Part One 13:02 2 Part Two 7:53 3 Part Three 15:51 4 Hymne an den heiligen Daniel (1997)† 12:14 www.naxos.com Made in the EU Kommentar auf Deutsch Booklet notes in English ൿ 5 Polymorphia (1961) 10:48 & 6 Polish Requiem: Chaconne (2005) 7:18 Ꭿ 2007 Naxos Rights International Ltd. Izabela Kłosi´nska, Soprano* • Agnieszka Rehlis, Mezzo-soprano* Adam Zdunikowski, Tenor* • Piotr Nowacki, Bass* Warsaw National Philharmonic Choir*† (Henryk Wojnarowski, choirmaster) Warsaw National Philharmonic Orchestra • Antoni Wit Sung texts are available at www.naxos.com/libretti/557980.htm 8.557980 Recorded from 5th to 7th September, 2005 (tracks 1-3), and on 29th September, 2005 (track 4), 8.557980 at Warsaw Philharmonic Hall, Poland Produced, engineered and edited by Andrzej Lupa and Aleksandra Nagórko (tracks 1 and 4), and Andrzej Sasin and Aleksandra Nagórko (tracks 2 and 3) • Publisher: Schott Musik Booklet notes: Richard Whitehouse • Cover image: Grey Black Cross by Sybille Yates (dreamstime.com). -

The Political Hamlet According to Jan Kott and Jerzy Grotowski

Multicultural Shakespeare: Translation, Appropriation and Performance Volume 17 Article 6 June 2018 The Political Hamlet According to Jan Kott and Jerzy Grotowski Wanda Świątkowska Jagiellonian University in Cracow Follow this and additional works at: https://digijournals.uni.lodz.pl/multishake Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Świątkowska, Wanda (2018) "The Political Hamlet According to Jan Kott and Jerzy Grotowski," Multicultural Shakespeare: Translation, Appropriation and Performance: Vol. 17 , Article 6. DOI: 10.18778/2083-8530.17.06 Available at: https://digijournals.uni.lodz.pl/multishake/vol17/iss32/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Humanities Journals at University of Lodz Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Multicultural Shakespeare: Translation, Appropriation and Performance by an authorized editor of University of Lodz Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Multicultural Shakespeare: Translation, Appropriation and Performance vol. 17 (32), 2018; DOI: 10.18778/2083-8530.17.06 ∗ Wanda Świątkowska The Political Hamlet According to Jan Kott and Jerzy Grotowski1 Abstract: The article presents political interpretations of Hamlet in Poland in the turbulent period of politcal changes between the mid-1950s and mid-1960s. The author discusses the relationships between Shakespeare’s tragedy and Polish political context as well as the influence of audience expectations in the specific interpretations. The selected performances are: Hamlet by Roman Zawistowski (at the Old Theatre in Cracow 1956) and Hamlet Study by Jerzy Grotowski (at the Laboratory Theatre of 13 Rows in Opole 1964). They both were hugely influenced by major commentators of Hamlet, i.e. -

Expanding Horizons: the International Avant-Garde, 1962-75

452 ROBYNN STILWELL Joplin, Janis. 'Me and Bobby McGee' (Columbia, 1971) i_ /Mercedes Benz' (Columbia, 1971) 17- Llttle Richard. 'Lucille' (Specialty, 1957) 'Tutti Frutti' (Specialty, 1955) Lynn, Loretta. 'The Pili' (MCA, 1975) Expanding horizons: the International 'You Ain't Woman Enough to Take My Man' (MCA, 1966) avant-garde, 1962-75 'Your Squaw Is On the Warpath' (Decca, 1969) The Marvelettes. 'Picase Mr. Postman' (Motown, 1961) RICHARD TOOP Matchbox Twenty. 'Damn' (Atlantic, 1996) Nelson, Ricky. 'Helio, Mary Lou' (Imperial, 1958) 'Traveling Man' (Imperial, 1959) Phair, Liz. 'Happy'(live, 1996) Darmstadt after Steinecke Pickett, Wilson. 'In the Midnight Hour' (Atlantic, 1965) Presley, Elvis. 'Hound Dog' (RCA, 1956) When Wolfgang Steinecke - the originator of the Darmstadt Ferienkurse - The Ravens. 'Rock All Night Long' (Mercury, 1948) died at the end of 1961, much of the increasingly fragüe spirit of collegial- Redding, Otis. 'Dock of the Bay' (Stax, 1968) ity within the Cologne/Darmstadt-centred avant-garde died with him. Boulez 'Mr. Pitiful' (Stax, 1964) and Stockhausen in particular were already fiercely competitive, and when in 'Respect'(Stax, 1965) 1960 Steinecke had assigned direction of the Darmstadt composition course Simón and Garfunkel. 'A Simple Desultory Philippic' (Columbia, 1967) to Boulez, Stockhausen had pointedly stayed away.1 Cage's work and sig- Sinatra, Frank. In the Wee SmallHoun (Capítol, 1954) Songsfor Swinging Lovers (Capítol, 1955) nificance was a constant source of acrimonious debate, and Nono's bitter Surfaris. 'Wipe Out' (Decca, 1963) opposition to himz was one reason for the Italian composer being marginal- The Temptations. 'Papa Was a Rolling Stone' (Motown, 1972) ized by the Cologne inner circle as a structuralist reactionary. -

My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 My Bloody Valentine's Loveless David R. Fisher Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS By David R. Fisher A thesis submitted to the College of Music In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of David Fisher on March 29, 2006. ______________________________ Charles E. Brewer Professor Directing Thesis ______________________________ Frank Gunderson Committee Member ______________________________ Evan Jones Outside Committee M ember The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables......................................................................................................................iv Abstract................................................................................................................................v 1. THE ORIGINS OF THE SHOEGAZER.........................................................................1 2. A BIOGRAPHICAL ACCOUNT OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE.………..………17 3. AN ANALYSIS OF MY BLOODY VALENTINE’S LOVELESS...............................28 4. LOVELESS AND ITS LEGACY...................................................................................50 BIBLIOGRAPHY..............................................................................................................63 -

An Analysis of Polish Devotion to the Catholic Church Under Communism Kathryn Burns Union College - Schenectady, NY

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2013 More Catholic than the Pope: An Analysis of Polish Devotion to the Catholic Church under Communism Kathryn Burns Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, and the European History Commons Recommended Citation Burns, Kathryn, "More Catholic than the Pope: An Analysis of Polish Devotion to the Catholic Church under Communism" (2013). Honors Theses. 638. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/638 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “More Catholic than the Pope”: An Analysis of Polish Devotion to the Catholic Church under Communism By Kathryn Burns ******************** Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of History UNION COLLEGE June 2013 Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………..........................................1 Chapter I. The Roman Catholic Church‟s Influence in Poland Prior to World War II…………………………………………………………………………………………………...4 Chapter II. World War II and the Rise of Communism……………….........................................38 Chapter III. The Decline and Demise of Communist Power……………….. …………………..63 Chapter IV. Conclusion………………………………………………………………………….76 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………………..78 ii Abstract Poland is home to arguably the most loyal and devout Catholics in Europe. A brief examination of the country‟s history indicates that Polish society has been subjected to a variety of politically, religiously, and socially oppressive forces that have continually tested the strength of allegiance to the Catholic Church. -

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES from The

EAST-CENTRAL EUROPEAN & BALKAN SYMPHONIES From the 19th Century To the Present A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers K-P MILOSLAV KABELÁČ (1908-1979, CZECH) Born in Prague. He studied composition at the Prague Conservatory under Karel Boleslav Jirák and conducting under Pavel Dedeček and at its Master School he studied the piano under Vilem Kurz. He then worked for Radio Prague as a conductor and one of its first music directors before becoming a professor of the Prague Conservatoy where he served for many years. He produced an extensive catalogue of orchestral, chamber, instrumental, vocal and choral works. Symphony No. 1 in D for Strings and Percussion, Op. 11 (1941–2) Marko Ivanovič/Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Symphony No. 2 in C for Large Orchestra, Op. 15 (1942–6) Marko Ivanovič/Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Symphony No. 3 in F major for Organ, Brass and Timpani, Op. 33 (1948-57) Marko Ivanovič//Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8) SUPRAPHON SU42022 (4 CDs) (2016) Libor Pešek/Alena Veselá(organ)/Brass Harmonia ( + Kopelent: Il Canto Deli Augei and Fišer: 2 Piano Concerto) SUPRAPHON 1110 4144 (LP) (1988) Symphony No. 4 in A major, Op. 36 "Chamber" (1954-8) Marko Ivanovic/Czech Chamber Philharmonic Orchestra, Pardubice ( + Martin·: Oboe Concerto and Beethoven: Symphony No. 1) ARCO DIVA UP 0123 - 2 131 (2009) Marko Ivanovič//Prague Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. -

Cult of the Most Holy Mother of God

CULT OF THE MOST HOLY MOTHER OF GOD Together with fidelity to Catholicism, Polish Christianity is distinquished by its Marian cult. The Marian cult began spreading throughout Poland from the dawn of Polish Christianity, and soon became part of everyday life and the spiritual culture of the nation. The oldest Polish churches are named after the Blessed Virgin Mary. The oldest Polish religious hymn, written by St. Adalbert, sung to the present day is Bogurodzica (Mother of God). Architectural monuments with Marian icons and sculptures testify to the antiquity of the Marian cult. There are over two hundred shrines with crowned, wonder–working images or the Mother or God in Poland. The largest shrine at Jasna Góra in Częstochowa, attracts thousands or pil- grims both from home and abroad. Polish royal families had the custom of paying homage to the Mary on Jasna Góra. Testimony to the Marian cult is also found in the monuments or Polish literature of all periods and types. Folkloristic creativity has transmitted to us a whole series or legends, poems, and songs about the Virgin Mary, as well as primitive folk sculptures and paintings. Mary has become part of Polish daily life through rites and feasts of the ecclesiastical year (the mysteries of Christ's and Mary's life), through ties to folk observances, through many devotions, songs, litanies, the rosary, the "Hours"(formerly chanted daily at home), and most of all through her wonder–working Częstochowa icon, a copy of which is found in almost every home. "O You, whose image is seen in every Polish cottage, Church, and store, in every sumptuous apartment, In the hand of the dying, and over the child's crib, And before whom both night and day shines the eternal light.