Expanding Horizons: the International Avant-Garde, 1962-75

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

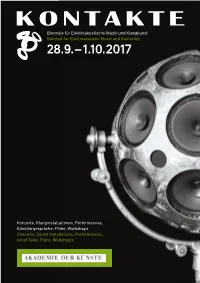

Konzerte, Klanginstallationen, Performances, Künstlergespräche, Filme, Workshops Concerts, Sound Installations, Performances, Artist Talks, Films, Workshops

Biennale für Elektroakustische Musik und Klangkunst Biennial for Electroacoustic Music and Sound Art 28.9. – 1.10.2017 Konzerte, Klanginstallationen, Performances, Künstlergespräche, Filme, Workshops Concerts, Sound Installations, Performances, Artist Talks, Films, Workshops 1 KONTAKTE’17 28.9.–1.10.2017 Biennale für Elektroakustische Musik und Klangkunst Biennial for Electroacoustic Music and Sound Art Konzerte, Klanginstallationen, Performances, Künstlergespräche, Filme, Workshops Concerts, Sound Installations, Performances, Artist Talks, Films, Workshops KONTAKTE '17 INHALT 28. September bis 1. Oktober 2017 Akademie der Künste, Berlin Programmübersicht 9 Ein Festival des Studios für Elektroakustische Musik der Akademie der Künste A festival presented by the Studio for Electro acoustic Music of the Akademie der Künste Konzerte 10 Im Zusammenarbeit mit In collaboration with Installationen 48 Deutsche Gesellschaft für Elektroakustische Musik Berliner Künstlerprogramm des DAAD Forum 58 Universität der Künste Berlin Hochschule für Musik Hanns Eisler Berlin Technische Universität Berlin Ausstellung 62 Klangzeitort Helmholtz Zentrum Berlin Workshop 64 Ensemble ascolta Musik der Jahrhunderte, Stuttgart Institut für Elektronische Musik und Akustik der Kunstuniversität Graz Laboratorio Nacional de Música Electroacústica Biografien 66 de Cuba singuhr – projekte Partner 88 Heroines of Sound Lebenshilfe Berlin Deutschlandfunk Kultur Lageplan 92 France Culture Karten, Information 94 Studio für Elektroakustische Musik der Akademie der Künste Hanseatenweg 10, 10557 Berlin Fon: +49 (0) 30 200572236 www.adk.de/sem EMail: [email protected] KONTAKTE ’17 www.adk.de/kontakte17 #kontakte17 KONTAKTE’17 Die zwei Jahre, die seit der ersten Ausgabe von KONTAKTE im Jahr 2015 vergangen sind, waren für das Studio für Elektroakustische Musik eine ereignisreiche Zeit. Mitte 2015 erhielt das Studio eine großzügige Sachspende ausgesonderter Studiotechnik der Deut schen Telekom, die nach entsprechenden Planungs und Wartungsarbeiten seit 2016 neue Produktionsmöglichkeiten eröffnet. -

The Rai Studio Di Fonologia (1954–83)

ELECTRONIC MUSIC HISTORY THROUGH THE EVERYDAY: THE RAI STUDIO DI FONOLOGIA (1954–83) Joanna Evelyn Helms A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2020 Approved by: Andrea F. Bohlman Mark Evan Bonds Tim Carter Mark Katz Lee Weisert © 2020 Joanna Evelyn Helms ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Joanna Evelyn Helms: Electronic Music History through the Everyday: The RAI Studio di Fonologia (1954–83) (Under the direction of Andrea F. Bohlman) My dissertation analyzes cultural production at the Studio di Fonologia (SdF), an electronic music studio operated by Italian state media network Radiotelevisione Italiana (RAI) in Milan from 1955 to 1983. At the SdF, composers produced music and sound effects for radio dramas, television documentaries, stage and film operas, and musical works for concert audiences. Much research on the SdF centers on the art-music outputs of a select group of internationally prestigious Italian composers (namely Luciano Berio, Bruno Maderna, and Luigi Nono), offering limited windows into the social life, technological everyday, and collaborative discourse that characterized the institution during its nearly three decades of continuous operation. This preference reflects a larger trend within postwar electronic music histories to emphasize the production of a core group of intellectuals—mostly art-music composers—at a few key sites such as Paris, Cologne, and New York. Through close archival reading, I reconstruct the social conditions of work in the SdF, as well as ways in which changes in its output over time reflected changes in institutional priorities at RAI. -

3770001904221.Pdf

This is America! Meredith Monk (b. 1942) 1 Ellis Island 3’02 Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990) Symphonic Dances from West Side Story (transcription: John Musto) 2 Prologue 4’18 3 Somewhere 4’29 4 Mambo 2’19 5 Cha-Cha 1’02 6 Meeting Scene 0'41 7 Cool 0’38 8 Fugue 3’02 9 Rumble 2’01 10 Finale 2’27 Philip Glass (b. 1937) Four Movements for Two Pianos 11 Movement 1 6’21 12 Movement 2 4’49 13 Movement 3 6’19 14 Movement 4 5’30 John Adams (b. 1947) Hallelujah Junction 15 Movement 1 6’43 16 Movement 2 2’52 17 Movement 3 5’58 TT: 62’34 3 THIS IS AMERICA! | VANESSA WAGNER & WILHEM LATCHOUMIA Entretien avec Vanessa Wagner et Wilhem Latchoumia Apparu au milieu des années 60 aux États-Unis, le courant minimaliste a longtemps tutoyé l’avant-garde avant de gagner, au fil des ans, une audience beaucoup plus large et de s’imposer comme une étape majeure de la musique contemporaine. Terry Riley, La Monte Young, Steve Reich et Philip Glass, tous américains, sont considérés comme les pionniers de ce courant. Si beaucoup de ces compositeurs contestent l’étiquette minimaliste, réductrice à leurs yeux, leur approche se rejoint dans la recherche de nouvelles structures musicales, comme l’emploi de motifs répétitifs, une certaine forme de dépouillement et l’emploi de certains procédés spécifiques (la technique de « phasing » de Reich, utilisant simultanément des enregistrements avec un léger décalage). Les minimalistes ont intégré de nombreuses influences pour nourrir leur travail, le jazz et l’improvisation pour Terry Riley, la mouvance expérimentale pour La Monte Young, la musique indienne pour Philip Glass, les cultures africaines pour Steve Reich. -

Ambiant Creativity Mo Fr Workshop Concerts Lectures Discussions

workshop concerts lectures discussions ambiant creativity »digital composition« March 14-18 2011 mo fr jérôme bertholon sebastian berweck ludger brümmer claude cadoz omer chatziserif johannes kreidler damian marhulets thomas a. troge iannis zannos // program thursday, march 17th digital creativity 6 pm, Lecture // Caught in the Middle: The Interpreter in the Digital Age and Sebastian Berweck contemporary ZKM_Vortragssaal music 6.45 pm, IMA | lab // National Styles in Electro- acoustic Music? thomas a. troged- Stipends of “Ambiant Creativity” and Sebastian fdfd Berweck ZKM_Vortragssaal 8 pm, Concert // Interactive Creativity with Sebastian Berweck (Pianist, Performer), works by Ludger Brümmer, Johannes Kreidler, Enno Poppe, Terry Riley, Giacinto Scelsi ZKM_Kubus friday, march 18th 6 pm, Lecture // New Technologies and Musical Creations Johannes Kreidler ZKM_Vortragsaal 6.45 pm, Round Table // What to Expect? Hopes and Problems of Technological Driven Art Ludger Brümmer, Claude Cadoz, Johannes Kreidler, Thomas A. Troge, Iannis Zannos ZKM_Vortragssaal 8 pm, Concert // Spatial Creativity, works by Jérôme Bertholon, Ludger Brümmer, Claude Cadoz, Omer Chatziserif, Damian Marhulets, Iannis Zannos ZKM_Kubus 10pm, Night Concert // Audiovisual Creativity with audiovisual compositions and dj- sets by dj deepthought and Damian Marhulets ZKM_Musikbalkon // the project “ambiant creativity” The “Ambiant Creativity” project aims to promote the potential of interdisciplinary coopera- tion in the arts with modern technology, and its relevance at the European Level. The results and events are opened to the general public. The project is a European Project funded with support from the European Commission under the Culture Program. It started on October, 2009 for a duration of two years. The partnership groups ACROE in France, ZKM | Karlsruhe in Germany and the Ionian University in Greece. -

City, University of London Institutional Repository

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. ORCID: 0000-0002-0047-9379 (2021). New Music: Performance Institutions and Practices. In: McPherson, G and Davidson, J (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Music Performance. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/25924/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] New Music: Performance Institutions and Practices Ian Pace For publication in Gary McPherson and Jane Davidson (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Music Performance (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021), chapter 17. Introduction At the beginning of the twentieth century concert programming had transitioned away from the mid-eighteenth century norm of varied repertoire by (mostly) living composers to become weighted more heavily towards a historical and canonical repertoire of (mostly) dead composers (Weber, 2008). -

Ulrich Buch Engl. Ulrich Buch Englisch

Stockhausen-Stiftung für Musik First edition 2012 Published by Stockhausen-Stiftung für Musik 51515 Kürten, Germany (Fax +49-[0] 2268-1813) www.stockhausen-verlag.com All rights reserved. Copying prohibited by law. O c Copyright Stockhausen-Stiftung für Musik 2012 Translation: Jayne Obst Layout: Kathinka Pasveer ISBN: 978-3-9815317-0-1 STOCKHAUSEN A THEOLOGICAL INTERPRETATION BY THOMAS ULRICH Stockhausen-Stiftung für Musik 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preliminary Remark .................................................................................................. VII Preface: Music and Religion ................................................................................. VII I. Metaphysical Theology of Order ................................................................. 3 1. Historical Situation ....................................................................................... 3 2. What is Music? ............................................................................................. 5 3. The Order of Tones and its Theological Roots ............................................ 7 4. The Artistic Application of Stockhausen’s Metaphysical Theology in Early Serialism .................................................. 14 5. Effects of Metaphysical Theology on the Young Stockhausen ................... 22 a. A Non-Historical Concept of Time ........................................................... 22 b. Domination Thinking ................................................................................ 23 c. Progressive Thinking -

Jazz Concert

Aritst Series presents: City of Tomorrow Woodind Quintet Wednesday, October 7, 2015 at 8 pm Lagerquist Concert Hall, Mary Baker Russell Music Center Pacific Lutheran University School of Arts and Communication / Department of Music present Artist Series presents: City of Tomorrow Woodwind Quintet Elise Blatchford, Flute Stuart Breczinski, Oboe Rane Moore, Clarinet Nanci Belmont, Bassoon Leander Star, Horn Wednesday, October 7, 2015, at 8 pm Lagerquist Concert Hall, Mary Baker Russell Music Center Welcome to Lagerquist Concert Hall. Please disable the audible signal on all watches, pagers and cellular phones for the duration of the concert. Use of cameras, recording equipment and all digital devices is not permitted in the concert hall. PROGRAM Rotary........................................................................................................... Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928-2007) Blow (1989) .............................................................................................................Franco Donatoni (1927-2000) INTERMISSION Daedalus ........................................................................................................................... John Aylward (b. 1980) East Wind ......................................................................................................................... Shulamit Ran (b. 1949) Elise Blatchford, flute Music for Breathing .............................................................................................................. Nat Evans (b. 1980) About the -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Performing Percussion in an Electronic World: An Exploration of Electroacoustic Music with a Focus on Stockhausen's Mikrophonie I and Saariaho's Six Japanese Gardens Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9b10838z Author Keelaghan, Nikolaus Adrian Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Performing Percussion in an Electronic World: An Exploration of Electroacoustic Music with a Focus on Stockhausen‘s Mikrophonie I and Saariaho‘s Six Japanese Gardens A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts by Nikolaus Adrian Keelaghan 2016 © Copyright by Nikolaus Adrian Keelaghan 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Performing Percussion in an Electronic World: An Exploration of Electroacoustic Music with a Focus on Stockhausen‘s Mikrophonie I and Saariaho‘s Six Japanese Gardens by Nikolaus Adrian Keelaghan Doctor of Musical Arts University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Robert Winter, Chair The origins of electroacoustic music are rooted in a long-standing tradition of non-human music making, dating back centuries to the inventions of automaton creators. The technological boom during and following the Second World War provided composers with a new wave of electronic devices that put a wealth of new, truly twentieth-century sounds at their disposal. Percussionists, by virtue of their longstanding relationship to new sounds and their ability to decipher complex parts for a bewildering variety of instruments, have been a favored recipient of what has become known as electroacoustic music. -

Pierre Boulez Rituel

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Pierre Boulez Born March 26, 1925, Montbrison, France. Currently resides in Paris, France. Rituel (In memoriam Bruno Maderna) Boulez composed this work in 1974 and 1975, and conducted the first performance on April 2, 1975, in London. The score calls for three flutes and two alto flutes, three oboes and english horn, three clarinets, E- flat clarinet and bass clarinet, alto saxophone, four bassoons, six horns, four trumpets, four trombones, six violins, two violas, two cellos, and a percussion battery consisting of tablas, japanese bells, woodblocks, japanese woodblock, maracas, tambourine, sizzle cymbal, turkish cymbal, chinese cymbal, cow bells, snare drums (with and without snares), guiros, bongo, claves, maracas-tubes, triangles, hand drums, castanets, temple blocks, tom-toms, log drum, conga, gongs, and tam-tams. Performance time is approximately twenty- five minutes. Bruno Maderna died on November 13, 1973. For many years he had been a close friend of Pierre Boulez (and a true friend of all those involved in new music activities) and a treasured colleague; like Boulez, he had made his mark both as a composer and as a conductor. “In fact, to get any real idea of what he was like as a person,” Boulez wrote at the time of his death, “the conductor and the composer must be taken together; for Maderna was a practical person, equally close to music whether he was performing or composing.” In 1974 Boulez began Rituel as a memorial piece in honor of Maderna. (In the catalog of his works, Rituel follows . explosante-fixe . ., composed in 1971 as a homage to Stravinsky.) The score was completed and performed in 1975. -

Department of Music to Present Concert of Contemporary Italian Music

Department of Music to present concert of contemporary Italian music April 26, 1974 Contemporary Italian music will be presented in a concert Tuesday, May 7, by the Department of Music of the University of California, San Diego. The free concert will be held at 8:15 p.m. in Building 409 on the Matthews campus. Works of young or little known Italian composers will be performed by music faculty and graduate students under the direction of Roberto Laneri. The program will include "Gesti" for piano and "Variazioni su 'Fur Elise' di Beethoven" by Guiseppe Chiari, "Introduzione, Musique de Nuit e Toccata" for clarinet and percussion by Mauro Bortolotti and "Tre Piccoli Pezzi" for flute, oboe and clarinet by Aldo Clementi. Other works will be four songs by Laneri: a selection from "Black Ivory," "George Arvanitis at the Cafe Blue Note - 2:00 a.m. or so," "Per Guiseppe Chiari" and "Imaginary Crossroads #1." The performance will also include "VII" for voice and saxophone by Giacinto Scelsi and "Note e Non" for flute, trombone, violincello, contrabass and percussion by Giancarlo Schiaffini. Chiari, a resident of Florence, is considered a Dada musician. His work is viewed as an expression of revolution by the common people against the repressive division of work in class-oriented societies. Brotolotti and Clementi are composition teachers who helped establish the Nuova Consonanza, a music association for furthering new music in Rome. Their music is transitional between the post-Webern avant-garde style and the work of younger composers. Laneri, a clarinetist and composer, is a Ph.D. -

AMRC Journal Volume 21

American Music Research Center Jo urnal Volume 21 • 2012 Thomas L. Riis, Editor-in-Chief American Music Research Center College of Music University of Colorado Boulder The American Music Research Center Thomas L. Riis, Director Laurie J. Sampsel, Curator Eric J. Harbeson, Archivist Sister Dominic Ray, O. P. (1913 –1994), Founder Karl Kroeger, Archivist Emeritus William Kearns, Senior Fellow Daniel Sher, Dean, College of Music Eric Hansen, Editorial Assistant Editorial Board C. F. Alan Cass Portia Maultsby Susan Cook Tom C. Owens Robert Fink Katherine Preston William Kearns Laurie Sampsel Karl Kroeger Ann Sears Paul Laird Jessica Sternfeld Victoria Lindsay Levine Joanne Swenson-Eldridge Kip Lornell Graham Wood The American Music Research Center Journal is published annually. Subscription rate is $25 per issue ($28 outside the U.S. and Canada) Please address all inquiries to Eric Hansen, AMRC, 288 UCB, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309-0288. Email: [email protected] The American Music Research Center website address is www.amrccolorado.org ISBN 1058-3572 © 2012 by Board of Regents of the University of Colorado Information for Authors The American Music Research Center Journal is dedicated to publishing arti - cles of general interest about American music, particularly in subject areas relevant to its collections. We welcome submission of articles and proposals from the scholarly community, ranging from 3,000 to 10,000 words (exclud - ing notes). All articles should be addressed to Thomas L. Riis, College of Music, Uni ver - sity of Colorado Boulder, 301 UCB, Boulder, CO 80309-0301. Each separate article should be submitted in two double-spaced, single-sided hard copies. -

Spectralism in the Saxophone Repertoire: an Overview and Performance Guide

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY Spectralism in the Saxophone Repertoire: An Overview and Performance Guide A PROJECT DOCUMENT SUBMITTED TO THE BIENEN SCHOOL OF MUSIC IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS for the degree DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS Program of Saxophone Performance By Thomas Michael Snydacker EVANSTON, ILLINOIS JUNE 2019 2 ABSTRACT Spectralism in the Saxophone Repertoire: An Overview and Performance Guide Thomas Snydacker The saxophone has long been an instrument at the forefront of new music. Since its invention, supporters of the saxophone have tirelessly pushed to create a repertoire, which has resulted today in an impressive body of work for the yet relatively new instrument. The saxophone has found itself on the cutting edge of new concert music for practically its entire existence, with composers attracted both to its vast array of tonal colors and technical capabilities, as well as the surplus of performers eager to adopt new repertoire. Since the 1970s, one of the most eminent and consequential styles of contemporary music composition has been spectralism. The saxophone, predictably, has benefited tremendously, with repertoire from Gérard Grisey and other founders of the spectral movement, as well as their students and successors. Spectral music has continued to evolve and to influence many compositions into the early stages of the twenty-first century, and the saxophone, ever riding the crest of the wave of new music, has continued to expand its body of repertoire thanks in part to the influence of the spectralists. The current study is a guide for modern saxophonists and pedagogues interested in acquainting themselves with the saxophone music of the spectralists.