Toccata Classics TOCC 0126 Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The John and Anna Gillespie Papers an Inventory of Holdings at the American Music Research Center

The John and Anna Gillespie papers An inventory of holdings at the American Music Research Center American Music Research Center, University of Colorado at Boulder The John and Anna Gillespie papers Descriptive summary ID COU-AMRC-37 Title John and Anna Gillespie papers Date(s) Creator(s) Repository The American Music Research Center University of Colorado at Boulder 288 UCB Boulder, CO 80309 Location Housed in the American Music Research Center Physical Description 48 linear feet Scope and Contents Papers of John E. "Jack" Gillespie (1921—2003), Professor of music, University of California at Santa Barbara, author, musicologist and organist, including more than five thousand pieces of photocopied sheet music collected by Dr. Gillespie and his wife Anna Gillespie, used for researching their Bibliography of Nineteenth Century American Piano Music. Administrative Information Arrangement Sheet music arranged alphabetically by composer and then by title Access Open Publication Rights All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the American Music Research Center. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], John and Anna Gillespie papers, University of Colorado, Boulder Index Terms Access points related to this collection: Corporate names American Music Research Center - Page 2 - The John and Anna Gillespie papers Detailed Description Bibliography of Nineteenth-Century American Piano Music Music for Solo Piano Box Folder 1 1 Alden-Ambrose 1 2 Anderson-Ayers 1 3 Baerman-Barnes 2 1 Homer N. Bartlett 2 2 Homer N. Bartlett 2 3 W.K. Bassford 2 4 H.H. Amy Beach 3 1 John Beach-Arthur Bergh 3 2 Blind Tom 3 3 Arthur Bird-Henry R. -

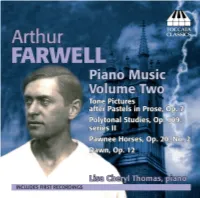

Toccata Classics TOCC0222 Notes

ARTHUR FARWELL: PIANO MUSIC, VOLUME TWO by Lisa Cheryl Thomas When Arthur Farwell, in his late teens and studying electrical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, heard the ‘Unfinished’ Symphony for the first time, he decided that he was going to be not an engineer but a composer. Born in St Paul, Minnesota, on 23 April 1872,1 he was already an accomplished musician: he had learned the violin as a child and often performed in a duo with his pianist elder brother Sidney, in public as well as at home; indeed, he supported himself at college by playing in a sextet. His encounter with Schubert proved detrimental to his engineering studies – he had to take remedial classes in the summer to be able to pass his exams and graduate in 1893 – but his musical awareness grew rapidly, not least though his friendship with an eccentric Boston violin prodigy, Rudolph Rheinwald Gott, and frequent attendances at Boston Symphony Orchestra concerts (as a ‘standee’: he couldn’t afford a seat). Charles Whitefield Chadwick (1854–1931), one of the most prominent of the New England school of composers, offered compositional advice, suggesting, too, that Farwell learn to play the piano as soon as possible. Edward MacDowell (1860–1908), perhaps the leading American Romantic composer, looked over his work from time to time – Farwell’s finances forbade regular study with such an eminent man. But he could afford counterpoint lessons with the organist P Homer Albert Norris (1860–1920), who had studied in Paris with Dubois, Gigout and Guilmant, and piano lessons with Thomas P. -

Fifty Years Later: a Promise Fulfilled, in True Western Style

the ncOLIVIAhor Volume V, No. 1 A MEILY SOCIETY Winter 2007 Fifty Years Later: A Promise Fulfilled, in True Western Style n May 6, 2006, Catherine Suzanne “Sue” the children were older, I began to investigate the pos- OMcLaughlin Montgomery ’56 did Miss sibility of finishing my degree. At Oral Roberts Uni- Peabody proud. She graduated! True, she marched into versity I made the most progress; however, we moved Kumler Chapel with the Western Program class of 2006 to Illinois before I fin- rather than the Western College for Women class of ished! But we did move to a university 1956, but in many ways the 50-year delay made the oc- town, Charleston, casion all the more meaningful. home of Eastern Illi- As she wrote to her friends and family — who at- nois University. I pe- tended some 22 strong — “If I had graduated 50 years titioned for my degree ago we all would not be meeting on this day ... Many and was accepted of you would have missed the ceremony, the reunion of into their program. I thought I just might family and friends and the celebration.” Two Western grads: Sue Montgom- make it there. ery ’56, ’06 and daughter-in-law She told her story in this letter to Miami’s Presi- Oh, no, my hus- Allison Schweser Montgomery ’93 dent David Hodge: band had a stroke and October 26, 2006 we again had to move. This time to Leesburg, Florida, so he could be in warm weather. As you must have Dear President Hodge, guessed, no degree completed. -

Volume 46, Number 01 (January 1928) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 1-1-1928 Volume 46, Number 01 (January 1928) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 46, Number 01 (January 1928)." , (1928). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/752 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Journal of the ^Musical Home Everywhere THE ETUDE ) ''Music MCagazi January 1928 NEW YEARS AMBITIONS Panted by C. W. Snyder PRICE 25 CENTS $2.00 A YEAR •/ ' * ' . • - - - V ■ / * ETV D E jssMastf-r ift 1 Outstanding Piano Composen Whose Works Are Worth Knowing festers fjruguay.H Canada,’ tiS* STjE? Auditor! Td WARD^JwOTtHHIPOTER “? , Subscrib/rs We will gladly send any ot tnese compositions to piano teachers, allowing the privilege of ex¬ amining them on our “On Sale” plan and per¬ mitting the return ofot those not desired.aesirea. Askask forior “On Order Blank and the details of ?his helpful plan if you have never enjoyed its jVL/ 12 IS d-1 ffir n kJ> PRINTED IN THE UN,TED STATES OP AMERICA * — ' - ™L,SHE, > -V THEODORE PRESSER CO. -

The American Stravinsky

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY The Style and Aesthetics of Copland’s New American Music, the Early Works, 1921–1938 Gayle Murchison THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS :: ANN ARBOR TO THE MEMORY OF MY MOTHERS :: Beulah McQueen Murchison and Earnestine Arnette Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2012 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ϱ Printed on acid-free paper 2015 2014 2013 2012 4321 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-472-09984-9 Publication of this book was supported by a grant from the H. Earle Johnson Fund of the Society for American Music. “Excellence in all endeavors” “Smile in the face of adversity . and never give up!” Acknowledgments Hoc opus, hic labor est. I stand on the shoulders of those who have come before. Over the past forty years family, friends, professors, teachers, colleagues, eminent scholars, students, and just plain folk have taught me much of what you read in these pages. And the Creator has given me the wherewithal to ex- ecute what is now before you. First, I could not have completed research without the assistance of the staff at various libraries. -

Volume 65, Number 08 (August 1947) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 8-1-1947 Volume 65, Number 08 (August 1947) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 65, Number 08 (August 1947)." , (1947). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/181 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. XUQfr JNftr o 10 I s vation Army Band, has retired, after an AARON COPLAND’S Third Symphony unbroken record of sixty-four years’ serv- and Ernest Bloch’s Second Quartet have ice as Bandmaster in the Salvation Army. won the Award of the Music Critics Cir- cle of New York as the outstanding music American orchestral and chamber THE SALZBURG FESTI- BEGINNERS heard for the first time in New York VAL, which opened on PIANO during the past season. YOUNG July 31, witnessed an im- FOB portant break with tra- JOHN ALDEN CARPEN- dition when on August TER, widely known con- 6 the world premiere of KEYBOARD TOWN temporary American Gottfried von Einem’s composer, has been opera, “Danton’s Tod,” By Louise Robyn awarded the 1947 Gold was produced. -

August 1940) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 8-1-1940 Volume 58, Number 08 (August 1940) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 58, Number 08 (August 1940)." , (1940). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/258 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. M V — — .. — — PSYCHOLOGY FOR THE MUSIC TEACHER Swisher ' By Waller Samuel Thurlow been bought than any More copies of this book have other music practical working reference book issued in recent years. A text. A real improve his hold on students and hel D to the teacher who wishes to interest and Personality Read Contents. Music Study , Peuckota, leal “Those Who and attention. Learn, The .Material with Mhtch He Work. Suggestions f Types How ITe r 3 Lieurance and bibliographies and imitation Questions, suggestions, at end of quotations. each chapter. Illustrated with musical Who Study Move Ahead wam^ScB men The American Composer FROM SONG TO SYMPHONY g PUBLISHED MONTHLY Has Revealed So Successfully By Daniel Gregory Mason By Theodore Presser Co., Philadelphia, pa. Lazy Minds Lie Asleep In Bed” in Lore While Second Year ASD ADVISORY STAFF Romance, and Tribal "A Study Course in Music Understanding’’ EDITORIAL The Beauty, Adopted by The National Federation of Music Clubs DR. -

FSU ETD Template

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2018 Rooted in America: The Roy Harris and Henry Cowell Sonatas for Violin and Piano Marianna Cutright Brickle Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC ROOTED IN AMERICA: THE ROY HARRIS AND HENRY COWELL SONATAS FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO By MARIANNA CUTRIGHT BRICKLE A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music 2018 Marianna Brickle defended this treatise on April 2, 2018. The members of the supervisory committee were: Corinne Stillwell Professor Directing Treatise Denise Von Glahn University Representative Shannon Thomas Committee Member Benjamin Sung Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that this treatise has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii To my husband, David Brickle and my parents, Wanda and Edwin Cutright, for their unwavering love and support. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my thanks to all of my committee members: Professor Corinne Stillwell, Dr. Denise Von Glahn, Dr. Benjamin Sung, and Dr. Shannon Thomas for their time, support, and insightful contributions to this project. I extend special thanks to my violin teacher Corinne Stillwell for her pearls of wisdom and her mentorship. Without her guidance, this project would not have been possible. The growth that I have experienced in the past five years, I owe largely to her. Thanks to Denise Von Glahn for her Music in the United States II class, that introduced me to Roy Harris, and helped me grow as a writer. -

Download Finding

National Federation of Music Clubs Records This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit April 05, 2018 Describing Archives: A Content Standard National Federation of Music Clubs Indianapolis, Indiana National Federation of Music Clubs Records Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 5 History and Governance.......................................................................................................................... 5 Proceedings, Minutes, Reports, Programs.............................................................................................17 Financial/Legal/Administrative..............................................................................................................34 NFMC Publications............................................................................................................................... 59 Presidential papers................................................................................................................................. 78 Activities/Projects/Programs..................................................................................................................82 Scrapbooks.......................................................................................................................................... -

Native American Elements in Piano Repertoire by the Indianist And

NATIVE AMERICAN ELEMENTS IN PIANO REPERTOIRE BY THE INDIANIST AND PRESENT-DAY NATIVE AMERICAN COMPOSERS Lisa Cheryl Thomas, B.M.E., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2010 APPROVED: Adam Wodnicki, Major Professor Steven Friedson, Minor Professor Joseph Banowetz, Committee Member Jesse Eschbach, Chair of the Division of Keyboard Studies Graham Phipps, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Michael Monticino, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Thomas, Lisa Cheryl. Native American Elements in Piano Repertoire by the Indianist and Present-Day Native American Composers. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2010, 78 pp., 25 musical examples, 6 illustrations, references, 66 titles. My paper defines and analyzes the use of Native American elements in classical piano repertoire that has been composed based on Native American tribal melodies, rhythms, and motifs. First, a historical background and survey of scholarly transcriptions of many tribal melodies, in chapter 1, explains the interest generated in American indigenous music by music scholars and composers. Chapter 2 defines and illustrates prominent Native American musical elements. Chapter 3 outlines the timing of seven factors that led to the beginning of a truly American concert idiom, music based on its own indigenous folk material. Chapter 4 analyzes examples of Native American inspired piano repertoire by the “Indianist” composers between 1890-1920 and other composers known primarily as “mainstream” composers. Chapter 5 proves that the interest in Native American elements as compositional material did not die out with the end of the “Indianist” movement around 1920, but has enjoyed a new creative activity in the area called “Classical Native” by current day Native American composers. -

Roy Harris Papers

Roy Harris Papers Processed by the Music Division of the Library of Congress Music Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2010 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/perform.contact Catalog Record: http://lccn.loc.gov/2010562511 Finding aid encoded by Library of Congress Music Division, 2010 Finding aid URL: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/eadmus.mu010029 Latest revision: 2012 April Collection Summary Title: Roy Harris Papers Span Dates: 1893-1998 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1933-1979) Call No.: ML31.H37 Creator: Harris, Roy, 1898-1979 Extent: 6,450 items ; 88 containers ; 40.0 linear feet Language: Material in English Location: Music Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Roy Harris was an American composer. The collection contains materials that document his life and career, including manuscript scores, published and unpublished writings, correspondence, business papers, financial and legal documents, programs, publicity files, photographs, scrapbooks, work files, posters, clippings, and biographical materials. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Boulanger, Nadia--Correspondence. Cage, John--Correspondence. Foss, Lukas, 1922-2009--Correspondence. Harris, Johana--Correspondence. Harris, Johana. Harris, Roy, 1898-1979--Archives. Harris, Roy, 1898-1979--Correspondence. Harris, Roy, 1898-1979--Manuscripts. Harris, Roy, 1898-1979--Photographs. Harris, Roy, 1898-1979. Harris, Roy, 1898-1979. Harris, Roy, 1898-1979. Selections. Ormandy, Eugene, 1899-1985--Correspondence. Persichetti, Vincent, 1915-1987--Correspondence. Starker, Janos--Correspondence. Organizations Pittsburgh International Contemporary Music Festival. -

UNIVERSITY of CINCINNATI August 2005 Stephanie Bruning Doctor Of

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ The Indian Character Piece for Solo Piano (ca. 1890–1920): A Historical Review of Composers and Their Works D.M.A. Document submitted to the College-Conservatory of Music, University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Piano Performance August 2005 by Stephanie Bruning B.M. Drake University, Des Moines, IA, 1999 M.M. College-Conservatory of Music, University of Cincinnati, 2001 1844 Foxdale Court Crofton, MD 21114 410-721-0272 [email protected] ABSTRACT The Indianist Movement is a title many music historians use to define the surge of compositions related to or based on the music of Native Americans that took place from around 1890 to 1920. Hundreds of compositions written during this time incorporated various aspects of Indian folklore and music into Western art music. This movement resulted from many factors in our nation’s political and social history as well as a quest for a compositional voice that was uniquely American. At the same time, a wave of ethnologists began researching and studying Native Americans in an effort to document their culture. In music, the character piece was a very successful genre for composers to express themselves. It became a natural genre for composers of the Indianist Movement to explore for portraying musical themes and folklore of Native-American tribes.