Making America Operatic: Six Composers' Attempts at An

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Transformation of Pushkin's Eugene Onegin Into Tchaikovsky's Opera

THE TRANSFORMATION OF PUSHKIN'S EUGENE ONEGIN INTO TCHAIKOVSKY'S OPERA Molly C. Doran A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2012 Committee: Eftychia Papanikolaou, Advisor Megan Rancier © 2012 Molly Doran All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Eftychia Papanikolaou, Advisor Since receiving its first performance in 1879, Pyotr Il’yich Tchaikovsky’s fifth opera, Eugene Onegin (1877-1878), has garnered much attention from both music scholars and prominent figures in Russian literature. Despite its largely enthusiastic reception in musical circles, it almost immediately became the target of negative criticism by Russian authors who viewed the opera as a trivial and overly romanticized embarrassment to Pushkin’s novel. Criticism of the opera often revolves around the fact that the novel’s most significant feature—its self-conscious narrator—does not exist in the opera, thus completely changing one of the story’s defining attributes. Scholarship in defense of the opera began to appear in abundance during the 1990s with the work of Alexander Poznansky, Caryl Emerson, Byron Nelson, and Richard Taruskin. These authors have all sought to demonstrate that the opera stands as more than a work of overly personalized emotionalism. In my thesis I review the relationship between the novel and the opera in greater depth by explaining what distinguishes the two works from each other, but also by looking further into the argument that Tchaikovsky’s music represents the novel well by cleverly incorporating ironic elements as a means of capturing the literary narrator’s sardonic voice. -

The Magic Flute

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART the magic flute conductor Libretto by Emanuel Schikaneder Harry Bicket Saturday, December 29, 2018 production 1:00–2:45 PM Julie Taymor set designer George Tsypin costume designer Julie Taymor lighting designer The abridged production of Donald Holder The Magic Flute was made possible by a puppet designers Julie Taymor gift from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Michael Curry and Bill Rollnick and Nancy Ellison Rollnick choreographer Mark Dendy The original production of Die Zauberflöte was made possible by a revival stage director David Kneuss gift from Mr. and Mrs. Henry R. Kravis english adaptation J. D. McClatchy Additional funding was received from John Van Meter, The Annenberg Foundation, Karen and Kevin Kennedy, Bill Rollnick and Nancy Ellison Rollnick, Mr. and Mrs. William R. general manager Miller, Agnes Varis and Karl Leichtman, and Peter Gelb Mr. and Mrs. Ezra K. Zilkha jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2018–19 SEASON The Magic Flute is The 447th Metropolitan Opera performance of performed without intermission. WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART’S This performance is being broadcast the magic flute live over The Toll Brothers– Metropolitan Opera conductor International Radio Harry Bicket Network, sponsored by Toll Brothers, in order of vocal appearance America’s luxury ® tamino second spirit homebuilder , with Ben Bliss* Eliot Flowers generous long- first l ady third spirit term support from Gabriella Reyes** N. Casey Schopflocher the Annenberg Foundation and second l ady spe aker GRoW @ Annenberg, Emily D’Angelo** Alfred Walker* The Neubauer Family third l ady sar astro Foundation, the Maria Zifchak Morris Robinson* Vincent A. -

German Jews in the United States: a Guide to Archival Collections

GERMAN HISTORICAL INSTITUTE,WASHINGTON,DC REFERENCE GUIDE 24 GERMAN JEWS IN THE UNITED STATES: AGUIDE TO ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS Contents INTRODUCTION &ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 1 ABOUT THE EDITOR 6 ARCHIVAL COLLECTIONS (arranged alphabetically by state and then city) ALABAMA Montgomery 1. Alabama Department of Archives and History ................................ 7 ARIZONA Phoenix 2. Arizona Jewish Historical Society ........................................................ 8 ARKANSAS Little Rock 3. Arkansas History Commission and State Archives .......................... 9 CALIFORNIA Berkeley 4. University of California, Berkeley: Bancroft Library, Archives .................................................................................................. 10 5. Judah L. Mages Museum: Western Jewish History Center ........... 14 Beverly Hills 6. Acad. of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences: Margaret Herrick Library, Special Coll. ............................................................................ 16 Davis 7. University of California at Davis: Shields Library, Special Collections and Archives ..................................................................... 16 Long Beach 8. California State Library, Long Beach: Special Collections ............. 17 Los Angeles 9. John F. Kennedy Memorial Library: Special Collections ...............18 10. UCLA Film and Television Archive .................................................. 18 11. USC: Doheny Memorial Library, Lion Feuchtwanger Archive ................................................................................................... -

I Hotel Westminster SMULLEN &

4 BOSTON, MASS., MONDAY, MAY 6, 1907 4I BOSONI MASS. M M 6 19 -, I HOLLIS STREET THEATRE. DON'T EAT T., E,MOSELEY & 00, There will be only one more UNTIL YOU VISIT Established 1847 week of the stay of "The Rogers TH A V NUE C AFE; Brothers in Ireland" at the Hollis For Steaks and Chops we Lead them all. For Street Theatre, and then these Everything First-Class at Moderate Prices. Tech merry comedians will take their 471, OLUMBUS AVE. leave of the Boston stage with the WM. PINK & GO. ' ' NEAR WEST NEWTON ST. Men jolliest vaudeville farce that they 14 have ever brought here. Ireland C. A. FATTEN & CO. is an ideal spot for the droll Ger- man comedians to visit, and the Merchant Tailors land of jigs and pretty colleens ap- DM 1. MFMC> SU ITS peals to everybody. The come- FIJL D SCsE SUIrS OUR SPECIAL OFFER $45 dians have hosts of new things this season, and the company which 43 TREMONT ST., Carney Bldg. they have in their support is better Slippers and Ithan any of its predecessors. DR. W. J. CURRIER PARK THEATRE. Pumps OFFICE HOURS 9 TO 4 ER'S I LAN Moccasins, Skates Boston is to have a week of 90 HUNTINGTON AVENUE and Snow Shoes Lu grand opera with Italian celebri- Refers by permission to Prof. T. H. Bartlett unch and Coffee House 145 Tremont Street ties at the Park Theatre, the at- traction being the San Carlo Opera Drawing-Inks Eternal Writing-Ink Company. Alice Nielsen, the ....... -

French Secular Music in Saint-Domingue (1750-1795) Viewed As a Factor in America's Musical Growth. John G

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1971 French Secular Music in Saint-Domingue (1750-1795) Viewed as a Factor in America's Musical Growth. John G. Cale Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Cale, John G., "French Secular Music in Saint-Domingue (1750-1795) Viewed as a Factor in America's Musical Growth." (1971). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2112. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2112 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 72-17,750 CALE, John G., 1922- FRENCH SECULAR MUSIC IN SAINT-DOMINGUE (1750-1795) VIEWED AS A FACTOR IN AMERICA'S MUSICAL GROWTH. The Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College;, Ph.D., 1971 Music I University Microfilms, A XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FRENCH SECULAR MUSIC IN SAINT-DOMINGUE (1750-1795) VIEWED AS A FACTOR IN AMERICA'S MUSICAL GROWTH A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The School of Music by John G. Cale B.M., Louisiana State University, 1943 M.A., University of Michigan, 1949 December, 1971 PLEASE NOTE: Some pages may have indistinct print. -

German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940 Academic attention has focused on America’sinfluence on European stage works, and yet dozens of operettas from Austria and Germany were produced on Broadway and in the West End, and their impact on the musical life of the early twentieth century is undeniable. In this ground-breaking book, Derek B. Scott examines the cultural transfer of operetta from the German stage to Britain and the USA and offers a historical and critical survey of these operettas and their music. In the period 1900–1940, over sixty operettas were produced in the West End, and over seventy on Broadway. A study of these stage works is important for the light they shine on a variety of social topics of the period – from modernity and gender relations to new technology and new media – and these are investigated in the individual chapters. This book is also available as Open Access on Cambridge Core at doi.org/10.1017/9781108614306. derek b. scott is Professor of Critical Musicology at the University of Leeds. -

San Franciscans Soon to Hear "The Secret of Suzanne" "STELLAR MEMBERS of the MUSICAL PROFESSION WHO ARE APPEARING BEFORE SAN FRANCISCO AUDIENCES

THE SAN FRANCISCO CALL, SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 10, 1912. 31 San Franciscans Soon to Hear "The Secret of Suzanne" "STELLAR MEMBERS OF THE MUSICAL PROFESSION WHO ARE APPEARING BEFORE SAN FRANCISCO AUDIENCES. certs early In December. The noted con^ tralto comes here under Greenbaum'i Wolf Ferrari's Opera to Be Played management and will be remembered for her success of last season. She wll appear before the St. Francis Muslca Afternoon of November 17 Art society Tuesday night, December 3 tenor, promises much of musical enter- tainment. Miss Turner is one of the Powell,* * violinist,* comes t( pianists, program Miss Maud By WALTER ANTHONY best of local and the conoertize for us during the first wee! has been selected carefully, as the fol- opportunity a change the concert in December. Among her selections sh< FRANCISCO'S first I complete in pro- lowing wll. show: is featuring a composition by the lat< to hear Wolf Ferrari's opera, i gram. By special request Miss Niel- Sonata, op. 18 (piano and riollnl Rubinstein Coleridge-Taylor, who dedicated his las j Two movements ?Moderate, con moto, SAN"The Secret of Susanne." will sen and Miss Swartz will sing the moderato var. 1. 11. concerto to the American violinist. "Mme. Butterfly." which (a) "From Out Thine Eyes My Songs Are1 . occur Sunday afternoon. November j duet from in Flowing" '...'. Ries IT. when the band of singers they created a sensation last year at i*b) "Time Enough". Nevln SUITOR PROVES FALSE: (C> gathered the production of "Molly Bawn" Lover WOMAN SEEKS DEATH together by Andreas Dip- Boston Puccini's Ballade, op. -

Insufficient Concern: a Unified Conception of Criminal Culpability

Insufficient Concern: A Unified Conception of Criminal Culpability Larry Alexandert INTRODUCTION Most criminal law theorists and the criminal codes on which they comment posit four distinct forms of criminal culpability: purpose, knowl- edge, recklessness, and negligence. Negligence as a form of criminal cul- pability is somewhat controversial,' but the other three are not. What controversy there is concerns how the lines between them should be drawn3 and whether there should be additional forms of criminal culpabil- ity besides these four.' My purpose in this Essay is to make the case for fewer, not more, forms of criminal culpability. Indeed, I shall try to demonstrate that pur- pose and knowledge can be reduced to recklessness because, like reckless- ness, they exhibit the basic moral vice of insufficient concern for the interests of others. I shall also argue that additional forms of criminal cul- pability are either unnecessary, because they too can be subsumed within recklessness as insufficient concern, or undesirable, because they punish a character trait or disposition rather than an occurrent mental state. Copyright © 2000 California Law Review, Inc. California Law Review, Incorporated (CLR) is a California nonprofit corporation. CLR and the authors are solely responsible for the content of their publications. f Warren Distinguished Professor of Law, University of San Diego. I wish to thank all the participants at the Symposium on The Morality of Criminal Law and its honoree, Sandy Kadish, for their comments and criticisms, particularly Leo Katz and Stephen Morse, who gave me comments prior to the event, and Joshua Dressler, whose formal Response was generous, thoughtful, incisive, and prompt. -

American 1Wusic Has Not Yet Uarrived'', Declares

' / 16 MUSICAL AMERICA September 6, 1919 store .employees who have their daily sings are a more efficient and happier lot of workers than those who do not, and American 1Wusic Has Not Yet uArrived'', he is convinced that the same will appl1 to singers in any other vocation. So it will not be a surprising thing Declares New Leader of Boston Symphony to enter the city hall at lunch time hereafter and hear city surveyors, tax Pierre Monteux, Back from F ranee, Begins Rehearsals-" Let Us Forget the War; It H as No Part collectors, policemen off duty and other eaters blending their melodious voices in in the Selection of Programs," Says Parisian the interpretation of a nything from jazz to grand opera. H. P. ~ OSTON, Aug. 29-With the arrival our best in literature and in poetry re 'dance s·pir·it' which characterizes Rus B her e this week of P ierre Moriteux, ma ins and always will be dear to us. sian music-not of the same style as NOTABLE MU SICIANS that of Russia but with a style char the new Boston Symphony Orchest r-a His View of American Music acteristically American. JOIN PEABODY STAFF conductor, the stage is fast being set f or "You ask whether we ar e t o develop "I think it will come. It will be very a Symphony season of rare distinct ion a true American type of music. Yes, or iginal; very American." Baltimore Conservatory Opens on Sept. and success. M. Monteux, with Mme. perhaps so, but the time has not arrived Mr. -

Toccata Classics TOCC0222 Notes

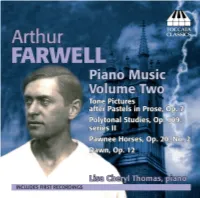

ARTHUR FARWELL: PIANO MUSIC, VOLUME TWO by Lisa Cheryl Thomas When Arthur Farwell, in his late teens and studying electrical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, heard the ‘Unfinished’ Symphony for the first time, he decided that he was going to be not an engineer but a composer. Born in St Paul, Minnesota, on 23 April 1872,1 he was already an accomplished musician: he had learned the violin as a child and often performed in a duo with his pianist elder brother Sidney, in public as well as at home; indeed, he supported himself at college by playing in a sextet. His encounter with Schubert proved detrimental to his engineering studies – he had to take remedial classes in the summer to be able to pass his exams and graduate in 1893 – but his musical awareness grew rapidly, not least though his friendship with an eccentric Boston violin prodigy, Rudolph Rheinwald Gott, and frequent attendances at Boston Symphony Orchestra concerts (as a ‘standee’: he couldn’t afford a seat). Charles Whitefield Chadwick (1854–1931), one of the most prominent of the New England school of composers, offered compositional advice, suggesting, too, that Farwell learn to play the piano as soon as possible. Edward MacDowell (1860–1908), perhaps the leading American Romantic composer, looked over his work from time to time – Farwell’s finances forbade regular study with such an eminent man. But he could afford counterpoint lessons with the organist P Homer Albert Norris (1860–1920), who had studied in Paris with Dubois, Gigout and Guilmant, and piano lessons with Thomas P. -

San Francisco Symphony Michael Tilson Thomas, Music Director

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS PROGRAM Tuesday, May 1, 2012, 8pm Zellerbach Hall San Francisco Symphony Michael Tilson Thomas, music director Jane Glover, conductor Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. 6 in B-flat major, bwv 1051 [Allegro] PROGRAM Adagio ma non tanto Allegro Jonathan Vinocour viola I Yun Jie Liu viola II George Frideric Handel (1685–1759) Water Music Suite No. 3 in G major, Barbara Bogatin viola da gamba I hwv 350 (1717) Marie Dalby Szuts viola da gamba II [Sarabande] or [Menuet] Rigaudons I and II Menuets I and II [Bourrées I and II] Handel Music for the Royal Fireworks, hwv 351 (1749) Overture Bourrée La Paix Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) Brandenburg Concerto No. 3 in G major, La Réjouissance bwv 1048 Menuet I [Allegro] Menuet II Adagio Allegro Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F major, bwv 1047 [Allegro] Andante Allegro assai Cal Performances’ 2011–2012 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. Nadya Tichman violin Robin McKee flute Jonathan Fischer oboe John Thiessen trumpet INTERMISSION 28 CAL PERFORMANCES CAL PERFORMANCES 29 PROGRAM NOTES PROGRAM NOTES George Frideric Handel (1685–1759) Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) Brandenburg Concerto No. 3 “for three presumably means a recorder when he just says Water Music Suite No. 3 in G major, hwv 350 Brandenburg Concerto No. 3 in G major, violins, three violas and three violoncelli, with flauto; however, as in most modern-instrument (1717) bwv 1048 bass for the harpsichord” (all the instrumenta- performances in large halls, the part will here be Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F major, tions are transcribed from Bach’s autograph) has translated to regular flute). -

CYLINDERS 2M = 2-Minute Wax, 4M WA= 4-Minute Wax, 4M BA = Edison Blue Amberol, OBT = Original Box and Top, OP = Original Descriptive Pamphlet

CYLINDERS 2M = 2-minute wax, 4M WA= 4-minute wax, 4M BA = Edison Blue Amberol, OBT = original box and top, OP = original descriptive pamphlet. ReproB/T = Excellent reproduction orange box and printed top Any mold on wax cylinders is always described. All cylinders are boxed (most in good quality boxes) with tops and are standard 2¼” diameter. All grading is visual. All cylinders EDISON unless otherwise indicated. “Direct recording” means recorded directly to cylinder, rather than dubbed from a Diamond-Disc master. This is used for cylinders in the lower 28200 series where there might be a question. BLANCHE ARRAL [s] 4108. Edison BA 28125. MIGNON: Je suis Titania (Thomas). Repro B/T. Just about 1-2. $40.00. ADELINA AGOSTINELLI [s]. Bergamo, 1882-Buenos Aires, 1954. A student in Milan of Giuseppe Quiroli, whom she later married, Agostinelli made her debut in Pavia, 1903, as Giordano’s Fedora. She appeared with success in South America, Russia, Spain, England and her native Italy and was on the roster of the Hammerstein Manhattan Opera, 1908-10. One New York press notice indicates that her rendering of the “Suicidio” from La Gioconda on a Manhattan Sunday night concert “kept her busy bowing in recognition to applause for three or four minutes”. At La Scala she was cast with Battistini in Simon Boccanegra and created for that house in 1911 the Marschallin in their first Rosenkavalier. Her career continued into the mid-1920s when she retired to Buenos Aires and taught. 4113. Edison BA 28159. LA TRAVIATA: Addio del passato (Verdi). ReproB/T.