LINER NOTES Recorded Anthology of American Music, Inc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Land of Harmony a M E R I C a N C H O R a L G E M S

invites you to The Land of Harmony A MERIC A N C HOR A L G EMS April 5 • Shaker Heights April 6 • Cleveland QClevelanduire Ross W. Duffin, Artistic Director The Land of Harmony American Choral Gems from the Bay Psalm Book to Amy Beach April 5, 2014 April 6, 2014 Christ Episcopal Church Historic St. Peter Church shaker heights cleveland 1 Star-spangled banner (1814) John Stafford Smith (1750–1836) arr. R. Duffin 2 Psalm 98 [SOLOISTS: 2, 3, 5] Thomas Ravenscroft (ca.1590–ca.1635) from the Bay Psalm Book, 1640 3 Psalm 23 [1, 4] John Playford (1623–1686) from the Bay Psalm Book, 9th ed. 1698 4 The Lord descended [1, 7] (psalm 18:9-10) (1761) James Lyon (1735–1794) 5 When Jesus wep’t the falling tear (1770) William Billings (1746–1800) 6 The dying Christian’s last farewell (1794) [4] William Billings 7 I am the rose of Sharon (1778) William Billings Solomon 2:1-8,10-11 8 Down steers the bass (1786) Daniel Read (1757–1836) 9 Modern Music (1781) William Billings 10 O look to Golgotha (1843) Lowell Mason (1792–1872) 11 Amazing Grace (1847) [2, 5] arr. William Walker (1809–1875) intermission 12 Flow gently, sweet Afton (1857) J. E. Spilman (1812–1896) arr. J. S. Warren 13 Come where my love lies dreaming (1855) Stephen Foster (1826–1864) 14 Hymn of Peace (1869) O. W. Holmes (1809–1894)/ Matthias Keller (1813–1875) 15 Minuet (1903) Patty Stair (1868–1926) 16 Through the house give glimmering light (1897) Amy Beach (1867–1944) 17 So sweet is she (1916) Patty Stair 18 The Witch (1898) Edward MacDowell (1860–1908) writing as Edgar Thorn 19 Don’t be weary, traveler (1920) [6] R. -

Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études" Qiao-Shuang Xian Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2002 Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études" Qiao-Shuang Xian Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Xian, Qiao-Shuang, "Rediscovering Frédéric Chopin's "Trois Nouvelles Études"" (2002). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2432. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2432 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. REDISCOVERING FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN’S TROIS NOUVELLES ÉTUDES A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Qiao-Shuang Xian B.M., Columbus State University, 1996 M.M., Louisiana State University, 1998 December 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF EXAMPLES ………………………………………………………………………. iii LIST OF FIGURES …………………………………………………………………………… v ABSTRACT …………………………………………………………………………………… vi CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………….. 1 The Rise of Piano Methods …………………………………………………………….. 1 The Méthode des Méthodes de piano of 1840 -

ALAN HOVHANESS: Meditation on Orpheus the Japan Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra William Strickland, Conducting

ALAN HOVHANESS: Meditation on Orpheus The Japan Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra William Strickland, conducting ALAN HOVHANESS is one of those composers whose music seems to prove the inexhaustability of the ancient modes and of the seven tones of the diatonic scale. He has made for himself one of the most individual styles to be found in the work of any American composer, recognizable immediately for its exotic flavor, its masterly simplicity, and its constant air of discovering unexpected treasures at each turn of the road. Meditation on Orpheus, scored for full symphony orchestra, is typical of Hovhaness’ work in the delicate construction of its sonorities. A single, pianissimo tam-tam note, a tone from a solo horn, an evanescent pizzicato murmur from the violins (senza misura)—these ethereal elements tinge the sound of the middle and lower strings at the work’s beginning and evoke an ambience of mysterious dignity and sensuousness which continues and grows throughout the Meditation. At intervals, a strange rushing sound grows to a crescendo and subsides, interrupting the flow of smooth melody for a moment, and then allowing it to resume, generally with a subtle change of scene. The senza misura pizzicato which is heard at the opening would seem to be the germ from which this unusual passage has grown, for the “rushing” sound—dynamically intensified at each appearance—is produced by the combination of fast, metrically unmeasured figurations, usually played by the strings. The composer indicates not that these passages are to be played in 2/4, 3/4, etc. but that they are to last “about 20 seconds, ad lib.” The notes are to be “rapid but not together.” They produce a fascinating effect, and somehow give the impression that other worldly significances are hidden in the juxtaposition of flow and mystical interruption. -

⁄Sþç}˛Ðn‚9Ô£ Rð˘¯Þ

559191 bk BEACH EU 25/05/2004 04:34pm Page 16 To her whose voice and loving hands fl Though I take the wings of morning, Op. 152 Can soothe our heart’s unrest, (1941) MERICAN LASSICS We bring these flowers, fragrant, fair, Though I take the wings of morning A C Our life her love hath blest! To the utmost sea, MAY FLOWERS Lyrics by Ana Mulford Addison Moody Yet my soul hath no sojourning Music by Amy Beach g1933 A.P. SCHMIDT CO. To outdistance Thee. Copyright Renewed and Assigned to SUMMY-BIRCHARD AMY BEACH MUSIC, a division of SUMMY-BIRCHARD INC. Though I climb to highest heaven, All Rights Reserved. Used by Permission of Warner Bros. ’Tis Thy dwelling high; Publications U.S. Inc. Though to death’s dark chamber given, Thou art standing by. fi I sought the Lord, Op. 142 (1937) Songs I sought the Lord, and afterward I knew If I say, the darkness hides me, He moved my soul to seek Him, seeking me; Turns my night to day; It was not I that found, O Saviour true; For with Thee no dark can find me, No, I was found of Thee. Shadows must away! The Year’s at the Spring Thou didst reach forth Thy hand and mine enfold; Even so, Thy hand shall lead me, I Sought the Lord I walked and sank not on the stormy sea; Flee Thee as I will; ’Twas not so much that I on Thee took hold, And Thy strong right arm shall hold me: As Thou, dear Lord, on me. -

April 1923) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 4-1-1923 Volume 41, Number 04 (April 1923) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 41, Number 04 (April 1923)." , (1923). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/700 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. >< T? <1 Theodore Presser Co., Publishers, Philadelphia, Pa. for Child Pianists Teachers Little Albums of Children .ptaliW P“e‘h Send for our interesting Pearls of Instruction in L “Catalogue of Juvenile •ollections makes them children and the Musical Publications This catalogue ha. many helpful The very appearance of these charming wotk8d«Cirfed._Thck.ndertgc9tK nd the covers are just as delightful. little musical gems beh ■ niiMc MOW HELPFUL WITH JUVEN1LES_ TEACHERS WILL FIND THESE / The World of Music Old Rhymes with New Tunes Birthday Jewels THE ETUDE APRIL 1923 Page 219 THE ETUDE AN UP-TO-THE-MINUTE LIST OF 1922-1923 New Music Etude Prize Contest Piano Solos and Duets, Vocal Solos, Sacred and Secular, PIANO SOLOS-VOCAL SOLOS Vocal Duets, Violin and Piano Numbers, ANTHEMS — PART SCfNGS $1,250.00 in Prizes PIANO SOLOS UTE TAKE pipleasure in making the following offer our Etude Prize Contest, being WsKSf of the real value of a contest of this der interest in composition and of of composers. -

Insights Into the Padrone, and Opera by George Whitefield Chadwick

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2004 American Verismo?: insights into The aP drone, and opera by George Whitefield hC adwick (13 November 1854 - 4 April 1931) Jon Steffen Truitt Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Truitt, Jon Steffen, "American Verismo?: insights into The aP drone, and opera by George Whitefield Chadwick (13 November 1854 - 4 April 1931)" (2004). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 304. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/304 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. AMERICAN VERISMO? INSIGHTS INTO THE PADRONE, AN OPERA BY GEORGE WHITEFIELD CHADWICK (13 NOVEMBER 1854 – 4 APRIL 1931) A Written Document Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Jon Steffen Truitt B.M., Baylor University, 1996 M.M., Baylor University, 1999 May 2004 AKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank the members of my committee: Dr. Lori Bade, Professor Robert Grayson, and Dr. Robert Peck for their support. I especially thank my major professor and the chair of my committee, Dr. Kyle Marrero, for his support and encouragement throughout my degree program. Thanks are also due to Dr. -

June 1911) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 6-1-1911 Volume 29, Number 06 (June 1911) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 29, Number 06 (June 1911)." , (1911). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/570 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 361 THE ETUDE -4 m UP-TO-DATE PREMIUMS _OF STANDARD QUALITY__ K MONTHLY JOURNAL FOR THE MUSICIAN, THE MUSIC STUDENT, AND ALL MUSIC LOVERS. Edited by JAMES FRANCIS COOKE », Alaska, Cuba, Porto Kieo, 50 WEBSTER’S NEW STANDARD 4 DICTIONARY Illustrated. NEW U. S. CENSUS In Combination with THE ETUDE money orders, bank check letter. United States postage ips^are always received for cash. Money sent gerous, and iponsible for its safe T&ke Your THE LAST WORD IN DICTIONARIES Contains DISCONTINUANCE isli the journal Choice o! the THE NEW WORDS Explicit directions Books: as well as ime of expiration, RENEWAL.—No is sent for renewals. The $2.50 Simplified Spelling, „„ ...c next issue sent you will lie printed tile date on wliicli your Webster’s Synonyms and Antonyms, subscription is paid up, which serves as a New Standard receipt for your subscription. -

Alan Hovhaness: Exile Symphony Armenian Rhapsodies No

ALAN HOVHANESS: EXILE SYMPHONY ARMENIAN RHAPSODIES NO. 1-3 | SONG OF THE SEA | CONCERTO FOR SOPRANO SaXOPHONE AND STRINGS [1] ARMENIAN RHAPSODY NO. 1, Op. 45 (1944) 5:35 SONG OF THE SEA (1933) ALAN HOVHANESS (1911–2000) John McDonald, piano ARMENIAN RHAPSODIES NO. 1-3 [2] I. Moderato espressivo 3:39 [3] II. Adagio espressivo 2:47 SONG OF THE SEA [4] ARMENIAN RHAPSODY NO. 2, Op. 51 (1944) 8:56 CONCERTO FOR SOPRANO SaXOPHONE CONCERTO FOR SOPRANO SaXOPHONE AND STRINGS, Op. 344 (1980) AND STRINGS Kenneth Radnofsky, soprano saxophone [5] I. Andante; Fuga 5:55 SYMPHONY NO. 1, EXILE [6] II. Adagio espressivo; Allegro 4:55 [7] III. Let the Living and the Celestial Sing 6:23 JOHN McDONALD piano [8] ARMENIAN RHAPSODY NO. 3, Op. 189 (1944) 6:40 KENNETH RADNOFSKY soprano saxophone SYMPHONY NO. 1, EXILE, Op. 17, No. 2 (1936) [9] I. Andante espressivo; Allegro 9:08 BOSTON MODERN ORCHESTRA PROJECT [10] II. Grazioso 3:31 GIL ROSE, CONDUCTOR [11] III. Finale: Andante; Presto 10:06 TOTAL 67:39 RETROSPECTIVE them. But I’ll print some music of my own as I get a little money and help out because I really don’t care; I’m very happy when a thing is performed and performed well. And I don’t know, I live very simply. I have certain very strong feelings which I think many people have Alan Hovhaness wrote music that was both unusual and communicative. In his work, the about what we’re doing and what we’re doing wrong. archaic and the avant-garde are merged, always with melody as the primary focus. -

Classical Music from the Late 19Th Century to the Early 20Th Century: the Creation of a Distinct American Musical Sound

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference Young Historians Conference 2019 May 1st, 12:30 PM - 1:45 PM Classical Music from the Late 19th Century to the Early 20th Century: The Creation of a Distinct American Musical Sound Ashley M. Christensen Lakeridge High School Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the Music Theory Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Christensen, Ashley M., "Classical Music from the Late 19th Century to the Early 20th Century: The Creation of a Distinct American Musical Sound" (2019). Young Historians Conference. 13. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2019/oralpres/13 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. CLASSICAL MUSIC FROM THE LATE 19th CENTURY TO THE EARLY 20th CENTURY: THE CREATION OF A DISTINCT AMERICAN MUSICAL SOUND Marked by the conflict of the Civil War, the late 19th century of American history marks an extremely turbulent time for the United States of America. As the young nation reached the second half of the century, idle threats of a Southern secession from the union bloomed into an all-encompassing conflict. However, through the turbulence of the war, American music persisted. Strengthened in battle, the ideas of a reconstructed American national identity started to form a distinctly different American culture and way of life. This is reflected in the nation’s shift in the music written after the war. -

Toccata Classics TOCC0222 Notes

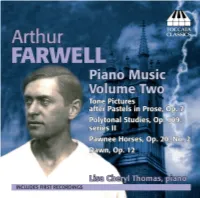

ARTHUR FARWELL: PIANO MUSIC, VOLUME TWO by Lisa Cheryl Thomas When Arthur Farwell, in his late teens and studying electrical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, heard the ‘Unfinished’ Symphony for the first time, he decided that he was going to be not an engineer but a composer. Born in St Paul, Minnesota, on 23 April 1872,1 he was already an accomplished musician: he had learned the violin as a child and often performed in a duo with his pianist elder brother Sidney, in public as well as at home; indeed, he supported himself at college by playing in a sextet. His encounter with Schubert proved detrimental to his engineering studies – he had to take remedial classes in the summer to be able to pass his exams and graduate in 1893 – but his musical awareness grew rapidly, not least though his friendship with an eccentric Boston violin prodigy, Rudolph Rheinwald Gott, and frequent attendances at Boston Symphony Orchestra concerts (as a ‘standee’: he couldn’t afford a seat). Charles Whitefield Chadwick (1854–1931), one of the most prominent of the New England school of composers, offered compositional advice, suggesting, too, that Farwell learn to play the piano as soon as possible. Edward MacDowell (1860–1908), perhaps the leading American Romantic composer, looked over his work from time to time – Farwell’s finances forbade regular study with such an eminent man. But he could afford counterpoint lessons with the organist P Homer Albert Norris (1860–1920), who had studied in Paris with Dubois, Gigout and Guilmant, and piano lessons with Thomas P. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 87, 1967-1968

1 J MIT t / ^ii "fv :' • "" ..."?;;:.»;:''':•::•> :.:::«:>:: : :- • :/'V *:.:.* : : : ,:.:::,.< ::.:.:.: .;;.;;::*.:?•* :-: ;v $mm a , '.,:•'•- % BOSTON ''•-% m SYMPHONY v. vi ORCHESTRA TUESDAY A SERIES EIGHTY-SEVENTH SEASON 1967-1968 -^^VTW-s^ Exquisite Sound From the palaces of ancient Egypt to the concert halls of our modern cities, the wondrous music of the harp has compelled attention from all peoples and all countries. Through this passage of time many changes have been made in the original design. The early instruments shown in drawings on the tomb of Rameses II (1292-1225 B.C.) were richly decorated but lacked the fore-pillar. Later the "Kinner" developed by the Hebrews took the form as we know it today. The pedal harp was invented about 1720 by a Bavarian named Hochbrucker and through this ingenious device it be- came possible to play in eight major and five minor scales complete. Today the harp is an important and familiar instrument providing the "Exquisite Sound" and special effects so important to modern orchestration and arrange- ment. The certainty of change makes necessary a continuous review of your insurance protection. We welcome the opportunity of providing this service for your business or personal needs. We respectfully invite your inquiry CHARLES H. WATKINS & CO. Richard P. Nyquist — Charles G. Carleton 147 Milk Street Boston, Massachusetts Telephone 542-1250 OBRION, RUSSELL & CO. Insurance of Every Description EIGHTY-SEVENTH SEASON 1967-1968 BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ERICH LEINSDORF Music Director CHARLES WILSON Assistant Conductor THE TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA INC. HENRY B. CABOT President TALCOTT M. BANKS Vice-President JOHN L. THORNDIKE Treasurer PHILIP K. -

SAM :: the Society for American Music

Custom Search About Us Membershipp Why SAM? Join or Ren ew Benefits Student Forum Institutions Listserv Social M edia For Members Conferences Future Conferences New Orleans 2019 Past Conferences Perlis Concerts 2018 Conference in Kansas City Awards & Fellowshipps Cambridge Award Housewright Disse rtation Minutes from Award Volume XLIV, No. 2 Low ens Article Award the Annual (Spring 2018) Lowens Book Award Business Tucker Student Pape r Contents Award Meeting Block Fellowshipp 2018 Conference in Kansas On a beautiful Charosh Fellowshipp City Cone Fellowshipp sunny day in early Crawford Fellow shipp Graziano Fellowshipp March, members of Business Meeting Hamm Fellowshipp Minutes the Society for Hampsong Fellows hipp Awards Lowens Fellowshipp American Music From the PresidentP McCulloh Fellowsh ipp SAM Brass Band McLucas Fellowshipp gathered in Salon 3 Celebrates Thirty Shirley Fellowshipp of the Years Southern Fellowsh ipp This and all other photos of the Kansas City meeting Student Forum Thomson Fellowshipp Intercontinental taken by Michael Broyles Reportp Tick Fellowshipp Walser-McClary Hotel Kansas City Fellowshipp for our annual business meeting. President Sandra Graham called the SAM’s Culture of Giving meeting to order at 4:33 p.m. and explained some of the major changes that Johnson Publication The PaulP Whiteman Subvention have been in the works for a while. First she discussed the new SAM logo and Sight & S ound Subvention Collection at Williams recognized the work of Board Members-at-Large Steve Swayne and Glenda Digital Lectures College Student Travel Goodman, who led a committee to find a graphic designer and then to provide feedback and guidance to the designer.