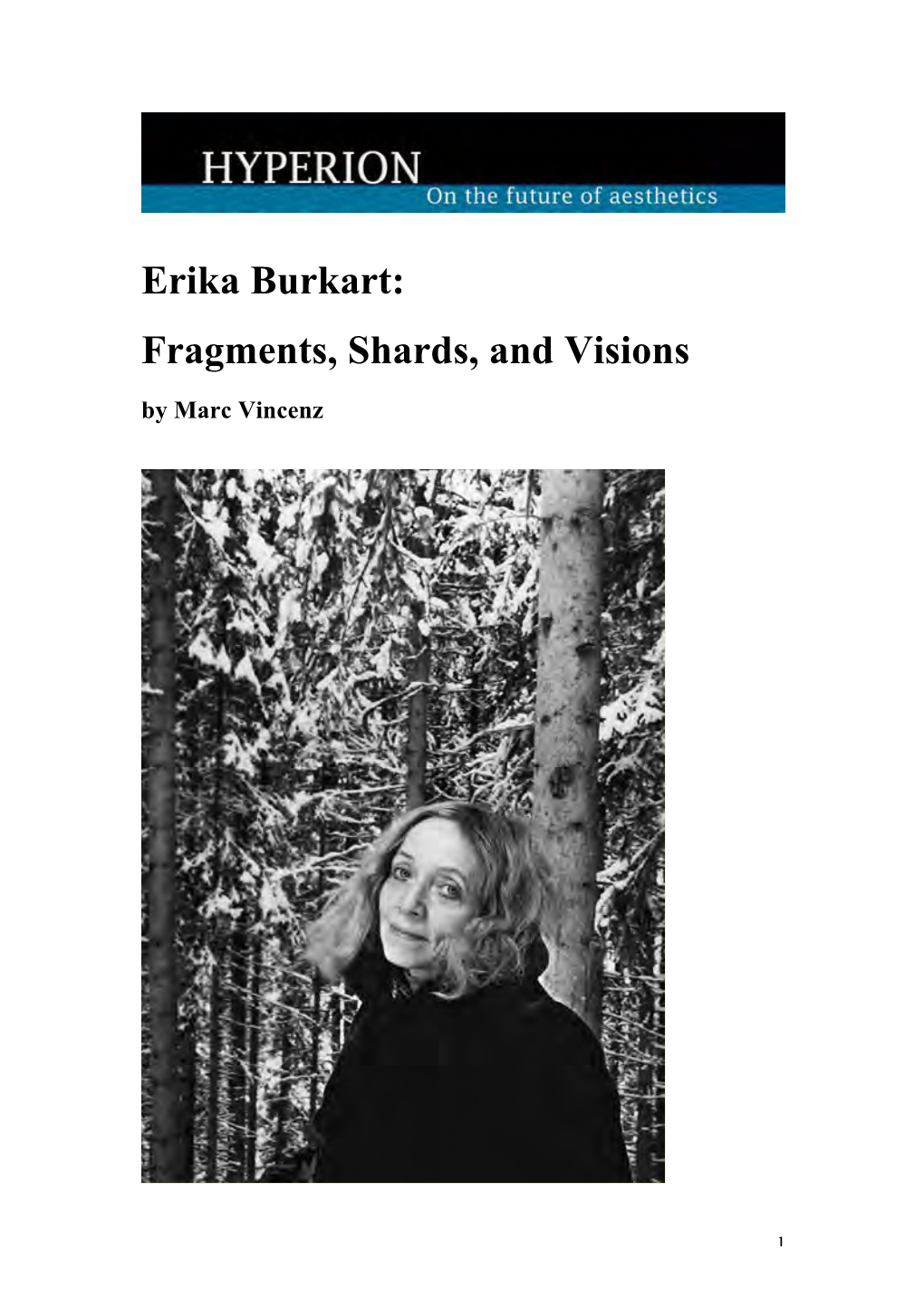

Erika Burkart: Fragments, Shards, and Visions by Marc Vincenz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Imagepresentation (PDF, 76 Pages, 8.9

THE CANTON OF AARGAU: ECONOMY AND EMPLOYMENT The Canton of Aargau is situated in Switzerland’s strongest economic area. Some 340 000 people are employed here in around 40 000 companies. An above-average proportion of these workers are active in the field of research and development. In fact, this is more than twice the national average. Our economic, tax and financial policies make the Canton of Aargau an attractive place of business for international corporations as well as for small and medium-sized businesses. The innovative Robotec Solutions AG known as a leading enterprise in robot applications. Standard & Poor’s has awarded the Canton of Aargau the rating AA+. And it’s no wonder. After all, we have a low unemployment rate, a moderate taxation rate, a strong economy and a high standard of living. These factors appeal to many well-known companies operating here in a wide range of industries – including ABB, GE, Franke, Syngenta and Roche. Our media landscape is equally diverse. In addition to AZ Medien, the canton boasts numerous other well-positioned local media companies. THE CANTON OF AARGAU: LIFE AND LIVING SINA SINGER The Canton of Aargau is currently home to some 670 000 people. That makes us the fourth-largest canton in Switzerland. Aargau is an urban area, yet also modest in size. The Canton of Aargau is within reasonable distance of anywhere – whether by car or public transport. However, for those who prefer to stay and be part of the local scene, Aargau has well-established communities and a wealth of vibrant traditions. -

Sendung Für Deutschlandradio Kultur Verrücktes Land Der Gletscher Und Des Pfirsichs

COPYRIGHT: Dieses Manuskript ist urheberrechtlichCOPYRIGHT geschützt. Es darf ohne GenehmigungDieses Manuskript nicht ist verwerteturheberrechtlich werden. geschützt. Insbesondere Es darf ohne G enehmigungdarf es nicht nicht verwertet werden. Insbesondere darf es nicht ganz oder teilweise oder in Auszügen ganz oder teilweise oder in Auszügen abgeschrieben oder in abgeschrieben oder in sonstiger Weise vervielfältigt werden. Für Rundfunkzwecke sonstigerdarf das ManuskriptWeise vervielfältigt nur mit Genehmigung werden. von Deutschlandradio Für Rundfunkzwecke Kultur benutzt darf werden. das Manuskript nur mit Genehmigung von DeutschlandRadio / Funkhaus Berlin benutzt werden. Sendung für DeutschlandRadio Kultur Verrücktes Land der Gletscher und des Pfirsichs. Neue Lyrik aus der Schweiz Von Uwe Stolzmann Musik. UNTERLEGEN. 1. O-Ton: Raphael Urweider. 0.00 vorfrühling. // teilweise schnee noch / verwehte helle zettel / ein eingezwängter bach / bringt wasser mit sich / und licht wie ein weh ein ach // gläserne käfer überrennen / ameisen als gäbe es sie nicht / der spatzenbock lässt von der / spätzin und hüpft stolz in den / noch nackten weißen baum Musik. ÜBERBLENDEN IN: 2. Atmo: Vögel. UNTERLEGEN. Autor: In einem Bergdorf im Süden der Schweiz steht ein junger Mann. Gleich neben der Kirche steht er, in Guttannen, einem 300-Seelen-Ort unterhalb des Grimselpasses. Der junge Mann, ein hochgeschätzter Lyriker, ist zu Besuch im Land seiner Kindheit. 2 3. O-Ton: Raphael Urweider. 17.49 / 18.28 Ich heiße Raphael Urweider, ich bin 1974 geboren und im Berner Oberland die ersten Jahre aufgewachsen, bis sieben – Autor: Der Vater, ein Pfarrer, schrieb in der Freizeit Gedichte und Kolumnen. Die schöngeistige Atmosphäre daheim habe ansteckend gewirkt, sagt Urweider. 4. O-Ton: Raphael Urweider. 21.54 Der Geruch auch von Bibliothek war im ganzen Haus zu spüren. -

Autorinnen Und Autoren Aus Baden-Württemberg Und Ihre Bücher Drama & Lyrik

Autorinnen und Autoren aus Baden-Württemberg und ihre Bücher Drama & Lyrik ........................................................................................................................... 11 Romane & Erzählungen ........................................................................................................ 19 Krimis ............................................................................................................................................35 Badenia & Württembergica ................................................................................................45 Kinder- & Jugendbücher ..................................................................................................... 51 Biografien & Lebenszeugnisse ..........................................................................................63 Literaturpreise & Stipendien .............................................................................................69 Die Wanderausstellung Autorinnen und Autoren aus Baden-Württemberg und ihre Bücher, präsentiert die Bandbreite der Schriftsteller des Landes. In Kooperation mit dem Ministerium für Wissenschaft, Forschung und Kunst Baden-Württemberg stellt der Börsenverein des Deutschen Buchhandels, Landesverband Baden-Württem- berg e. V., die Wanderausstellung zusammen. Die Auswahl der Bücher erfolgte in Zu- sammenarbeit mit Vertretern des Ministeriums, des Börsenvereins, des Verbandes deutscher Schriftsteller (VS), des Freien Deutschen Autorenverbandes (FDA), fachkun- digen Buchhändlerinnen -

Jahresbericht Des Vereins Zur Förderung Des Schweizerischen Literaturarchivs 2014

Jahresbericht des Vereins zur Förderung des Schweizerischen Literaturarchivs 2014 Jahresbericht Daniel de Roulet Robert Saitschick Hansjörg Schneider Hans Zbinden Zwischenbericht Ammann Verlag Impressum Jahresbericht Wieder liegt ein Jahr hinter uns. Mir als interimistisch gewählte Präsidentin obliegt es, eine Brücke zu schlagen zwischen dem vierjährigen Präsidium von Dieter Bachmann, dem wir die wiedergewonnene Freiheit für sein schrift- stellerisches Schaffen von Herzen gönnen und dem neuen Präsidenten, Prof. Thomas Geiser, der sein Amt vorbehältlich seiner Wahl in diesem Jahr an- treten wird. Die Mitgliederversammlung des Fördervereins fand in diesem Jahr in Zürich statt (12.5.2014). Als besonderes Erlebnis wurde dem Vorstand und den Vereinsmitgliedern im Anschluss an den offiziellen Teil die Teilnahme an einer Aufzeichnung des „Literaturclubs“ geboten. Im „Papiersaal“ konnte man einem der letzten „Literaturclubs“ unter der Leitung von Stefan Zwei- fel beiwohnen und gespannt den lebendigen und kontroversen Diskussio- nen zu ausgewählten Werken der deutschsprachigen Literatur folgen. An der Mitgliederversammlung wurden auch die Nachlässe präsentiert, de-ren Erschliessung ansteht; der Vorstand hat schliesslich drei Stipendien zu Paul Ilg (Lisa Hurter), Hermann Burger (Elias Zimmermann) und Gonzague de Reynold (Kristian Lasak) vergeben. Am Vorlass von Daniel de Roulet arbei- teten in diesem Jahr Elsa Nguyen und Vincent Yersin. Die Abschlussberich- te von letztjährigen Stipendiaten finden Sie nachfolgend (Michael Borter [Hansjörg Schneider]; -

Swiss National Library. 102Nd Annual Report 2015

Swiss National Library 102nd Annual Report 2015 Interactive artists‘ books: three-dimensional projections that visitors can manipulate using gestures, e.g. Dario Robbiani’s Design your cake and eat it too (1996). Architectural guided tour of the NL. The Gugelmann Galaxy: Mathias Bernhard drew on the Gugelmann Collection to create a heavenly galaxy that visitors can move around using a smartphone. Table of Contents Key Figures 2 Libraries are helping to shape the digital future 3 Main Events – a Selection 6 Notable Acquisitions 9 Monographs 9 Prints and Drawings Department 10 Swiss Literary Archives 11 Collection 13 “Viva” project 13 Acquisitions 13 Catalogues 13 Preservation and conservation 14 Digital Collection 14 User Services 15 Circulation 15 Information Retrieval 15 Outreach 15 Prints and Drawings Department 17 Artists’ books 17 Collection 17 User Services 17 Swiss Literary Archives 18 Collection 18 User Services 18 Centre Dürrenmatt Neuchâtel 19 Finances 20 Budget and Expenditures 2014/2015 20 Funding Requirement by Product 2013-2015 20 Commission and Management Board 21 Swiss National Library Commission 21 Management Board 21 Organization chart Swiss National Library 22 Thanks 24 Further tables with additional figures and information regarding this annual report can be found at http://www.nb.admin.ch/annual_report. 1 Key Figures 2014 2015 +/-% Swiss literary output Books published in Switzerland 12 711 12 208 -4.0% Non-commercial publications 6 034 5 550 -8.0% Collection Collections holdings: publications (in million units) 4.44 -

RENE CHAR Lou CASTEL KARI HUKKILA MAURA DEL SERRA ERIKA BURKART RAINALD GOETZ TH

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! RENE CHAR Lou CASTEL KARI HUKKILA MAURA DEL SERRA ERIKA BURKART RAINALD GOETZ TH. BERNHARD SCHILLER BARTOK-KODALY ELIO PETRI & MORE !!"#$%&'!"(()!(**%'!+)!,-+.! ! ! !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! ! ! ! vvv MAST HEAD Publisher: Contra Mundum Press Editor-in-Chief: Rainer J. Hanshe Senior Editors: Andrea Scrima & Carole Viers-Andronico PDF Design: Martin Rehtul Sucimsagro Logo Design: Liliana Orbach Advertising & Donations: Giovanni Piacenza (Donations can be made at: [email protected]) CMP Website: Bela Fenyvesi & Atrio LTD. Design: Alessandro Segalini Letters to the editors are welcome and should be e-mailed to: [email protected] Hyperion is published three times a year by Contra Mundum Press, Ltd. P.O. Box 1326, New York, NY 10276, U.S.A. W: http://contramundum.net For advertising inquiries, e-mail Giovanni Piacenza: [email protected] Contents © 2013 by Contra Mundum Press, Ltd. and each respective author. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from Contra Mundum Press, Ltd. After two years, all rights revert to the respective authors. If any work originally published by Contra Mundum Press is republished in any format, acknowledgement must be noted as following and a direct link to our site must be included in legible font at the bottom of the new publication: “Author/Editor, title, year -

Indice V Prefazione Di Roger Francillon 3 Avvertenza 7 Introduzione 25 Anelito Preromantico Gli Esordi Lirici in Lingua Tedesca

Indice V Prefazione di Roger Francillon 3 Avvertenza 7 Introduzione 25 Anelito preromantico Gli esordi lirici in lingua tedesca 27 Albrecht von Haller 31 Salomon Gessner 35 Lo spirito e la terra Il cosmopolitismo nella letteratura romanda fra sette e ottocento 39 Isabelle de Charrière 43 Germaine de Staël 47 Benjamin Constant 53 Charles-Victor de Bonstetten 56 Henri-Frédéric Amiel 59 Liberi e svizzeri Scrittori politici di lingua italiana 62 Vincenzo Dalberti 65 Stefano Franscini 69 Chimere dell’assoluto Narrativa svizzera tedesca dell’ottocento 72 Jeremias Gotthelf 84 Gottfried Keller 99 Conrad Ferdinand Meyer 111 Cari Spitteler 117 Rinascita di un’identità La letteratura retoromancia 121 Giachen Caspar Muoth 123 Peider Lansel 127 Idilli lacustri e montani Residui ottocenteschi nella narrativa svizzera italiana 129 Francesco Chiesa 135 Angelo Nessi 139 Giuseppe Zoppi 143 Tra simbolo e realtà La letteratura romanda agli esordi del novecento 146 Charles-Ferdinand Ramuz 155 Gonzague de Reynold 159 Guy de Pourtalès 162 Charles-Albert Cingria 165 Denis de Rougemont 169 Heimatlose Narrativa e poesia svizzere tedesche d’inizio novecento, fra critica sociale e straniamento 171 Jakob Bührer 175 Rudolf Jakob Humm 179 Kurt Guggenheim 183 Meinrad Inglin 188 Ludwig Hohl 192 Hermann Hesse 203 Robert Walser 214 Jakob Schaffner 218 Friedrich Glauser 225 Karl Stamm 227 Basta con le pannocchie al sole Poesia e prosa nella Svizzera italiana dagli anni quaranta 229 Pino Bernasconi 231 Felice Menghini 233 Remo Fasani 236 Amleto Pedroli 239 Ugo Canonica 243 -

Constantes Y Transformaciones En La Narrativa De La Suiza Alemana De

Configurando un nuevo espacio literario: constantes y transformaciones en la narrativa de la Suiza alemana de finales del siglo XX1 Configuring a new literary space: Constants and transformations in the fiction of German Swiss narrative at the end of the 20th Century Isabel HERNÁNDEZ Universidad Complutense de Madrid Departamento de Filología Alemana [email protected] El presente artículo analiza la situación de la literatura en la Suiza alemana a lo largo de la PALABRAS CLAVE segunda mitad del siglo XX, poniendo de relieve cómo, a pesar de los cambios y las trans- formaciones experimentadas durante ese periodo es posible observar una serie de Literatura constantes que se han mantenido a pesar del paso del tiempo y de la evolución histórica, suiza en RESUMEN política y sociológica del país, y gracias a las cuales es posible llegar a establecer una serie lengua alemana de géneros comunes a los autores de las distintas generaciones que han convivido y convi- Temas ven en este riquísimo escenario literario. Motivos Siglo XX The present article focuses on the situation of Literature in German Switzerland throughout KEY the second half of the 20th century. It will be demonstrated the existence of some constant WORDS factors in spite of the passage of time, the sociological and political evolution and the German Swiss changes and transformations experimented during that period. Those factors allow the de- literature ABSTRACT finition of common genres to authors who belong to different generations and who have Themes Motifs been coexisting in this rich literary scenery. 20th century SUMARIO 1. Situación de la narrativa en la Suiza alemana a finales del siglo XX. -

Inhaltsverzeichnis 13.10.2016

Inhaltsverzeichnis 13.10.2016 Martin Bodmer-Stiftung für einen Gottfried Keller-Preis Utoquai 55 Lieferschein-Nr.: 9755778 Postfach 1425 Abo-Nr.: 3003568 8032 Zürich Themen-Nr.: 840.1 Ausschnitte: 12 Folgeseiten: 11 Total Seitenzahl: 23 Auflage Seite 01.10.2016 Literarischer Monat 4'500 1 Die achtzehn Köpfe der Esther M. 01.10.2016 Literarischer Monat 4'500 7 Vorrede 01.10.2016 Literarischer Monat 4'500 10 Liebe Leserinnen und Leser 01.10.2016 Literarischer Monat 4'500 11 Skizze eines Porträts von Pietro De Marchi 10.10.2016 Der Landbote 27'811 15 Zwischen Alpträumen und Lonely Planet 10.10.2016 Zürcher Unterländer / Neues Bülacher Tagblatt 17'573 16 Zwischen Alpträumen und Lonely Planet 10.10.2016 Zürcher Oberländer 21'930 17 Zwischen Alpträumen und Lonely Planet 10.10.2016 lausanne-tourisme.ch Keine Angabe 18 Carte blanche Esther Montandon à l'AJAR 09.10.2016 agendalugano.ch Keine Angabe 19 La carta delle arance 10.10.2016 Corriere del Ticino 36'108 21 La poesia di De Marchi 10.10.2016 Anzeiger von Uster 6'663 22 Zwischen Alpträumen und Lonely Planet 11.10.2016 La Rivista / Camera di Commercio Italiana 8'000 23 Il Premio Gottfried Keller 2016 assegnato a Pietro De Marchi ARGUS der Presse AG Rüdigerstrasse 15 CH-8027 Zürich Tel. +41(44) 388 82 00 Mail [email protected] www.argus.ch Datum: 01.10.2016 Literarischer Monat Medienart: Print Themen-Nr.: 840.001 8037 Zürich Medientyp: Spezial- und Hobbyzeitschriften Abo-Nr.: 3003568 044/ 361 26 06 Auflage: 4'500 Seite: 39 www.schweizermonat.ch Erscheinungsweise: 4x jährlich Fläche: 151'818 mm² Die achtzehn Köpfe der Esther M. -

Swiss-German Literature 1945-2000

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Faculty Publications World Languages and Literatures 1-1-2005 Swiss-German Literature 1945-2000 Romey Sabalius San Jose State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/world_lang_pub Part of the German Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Romey Sabalius. "Swiss-German Literature 1945-2000" The Literary Encyclopedia and Literary Dictionary (2005). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the World Languages and Literatures at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Swiss-German Literature, 1945-2000 (1945-2000) Romey Sabalius (San José‚ State University) Places: Switzerland. For a nation with only seven million inhabitants, the literature of Switzerland is astonishingly complex. First, it should be noted that the small country actually possesses four literatures, respective to each of their language regions (German, French, Italian, and Rhaeto-Romansh). The literatures produced in the different linguistic regions have as little in common with each other as do German, French, and Italian literatures. Generally, the focal point for Swiss authors is the culture of the respective larger neighboring country. In the case of eastern Switzerland, where Rhaeto-Romansh is spoken by less than 100.000 people, authors publish primarily in German to reach a larger audience (Iso Camartin [1944-], Reto Hänny [1947-], Flurin Spescha [1958-2000]). In addition, the German language region of Switzerland is further divided by numerous dialects, which all differ immensely from standard German and to a significant extent from each other. -

Archivi E Lasciti

Dipartimento federale dell’interno DFI Ufficio federale della cultura UFC Biblioteca nazionale svizzera BN I vent’anni dell’Archivio svizzero di letteratura ASL Conferenza stampa dell’11 gennaio 2011 Archivi e lasciti Dal 1895 al 1988 Editions Bertil Galland 1994 (selezione; parte della colle- Jakob Haringer Benziger Verlagsarchiv zione di manoscritti della Otto F. Walter Rosmarie Buri Biblioteca nazionale svizze- Josef Viktor Widmann Gion Deplazes ra) Hans Rudolf Hilty S. Corinna Bille 1991 Pierre-Paul Plan Jakob Bührer Christoph Geiser Blaise Cendrars Friedrich Glauser 1995 Maurice Chappaz Golo Mann Jacques Chessex Jean Gebser Giovanni Orelli Gian Fontana Hermann Hesse Andri Peer Hannelise Hinterberger Hermann Hiltbrunner Pierre-Olivier Walzer Eduard Korrodi Erwin Jaeckle Gertrud Wilker Niklaus Meienberg Isabelle Kaiser Hans Walter Hans Kayser 1992 Maria Waser Cécile Lauber Alliance culturelle romande Heinz Weder Carl Albert Loosli Cla Biert Peter Lotar Otto Frei 1996 Emil Ludwig Rolf Geissbühler Georges Borgeaud Henry-Louis Mermod Hans-F. Geyer Patricia Highsmith Hans Morgenthaler Beat Sterchi Rolf Hochhuth Hans-Albrecht Moser Walter Vogt Paul Nizon Otto Nebel Jean Rudolf von Salis Gonzague de Reynold Alexander Seiler Rainer Maria Rilke 1993 William Ritter Ulrich Becher Romain Rolland Hans Boesch 1997 Max Rychner Marc Eigeldinger Edmond Bille Annemarie Schwarzenbach Jakob Flach Alexander Moritz Frey Carl Spitteler Peter Friedli (Fotosamm- Mariella Mehr Karl Stauffer-Bern lung) Silja Walter Otto Wirz Louise Gamper-Weber Emil Zbinden -

Zu Reto Hännys Prosawerken Vor Dem Hintergrund Sprachästhetischer Tendenzen in Der Deutschschweizer Literatur

ESTUDIOS LITERARIOS Revista de Filología Alemana ISSN: 1133-0406 https://dx.doi.org/10.5209/rfal.64353 Raffinierte Spracharabesken und rhythmische Wortkaskaden: zu Reto Hännys Prosawerken vor dem Hintergrund sprachästhetischer Tendenzen in der Deutschschweizer Literatur Dorota Sośnicka1 Recibido: 9 de enero de 2019 / Aceptado: 1 de febrero de 2019 Zusammenfassung. Der Aufsatz charakterisiert die wichtigsten Merkmale und Voraussetzungen der sprachästhetischen Tendenzen, wie sie sich seit Mitte der 1970er Jahre in der Deutschschweizer Gegenwartsliteratur bemerkbar machten, und überblickt das Schaffen einiger ‚Sprachartisten‘, die einerseits in Reaktion auf die Undurchschaubarkeit der Realität, andererseits als Ausdruck der zunehmenden Sprachreflexion und Sprachskepsis ihre hochartifiziellen Werke vorgelegt haben. Vor diesem Hintergrund konzentriert sich der Beitrag auf das Schaffen Reto Hännys als eines der radikalsten Sprachexperimentatoren, dessen von Intertextualität geprägte, bildstarke und rhythmisierte Texte im Hinblick auf ihre Problematik und Komposition besprochen werden. Schlüsselwörter: Sprachästhetik; Sprachartistik; Sprachskepsis; Literaturexperimente. [en] Ingenious Linguistc Arabesques and Rhythmic Word Cascades: the Prose Works of Reto Hänny in Relation to Aesthetic Linguistic Trends in German-Swiss Literature Abstract. This article characterises the most important features and assumptions of the trend towards aesthetic use of language which has been present in contemporary German-Swiss literature since the middle of the 1970s; it surveys the work of several ‘language artists’ whose highly contrived publications are a reaction on the one hand to the opacity of reality and on the other to an increasing scrutiny and distrust of language. Against this background, the article concentrates on the work of Reto Hänny as the most radical of the experimenters; his works, which are marked by extensive intertextuality, powerful imagery and rhythmic structures, are discussed in relation both to the problems they address and to the manner of their composition.