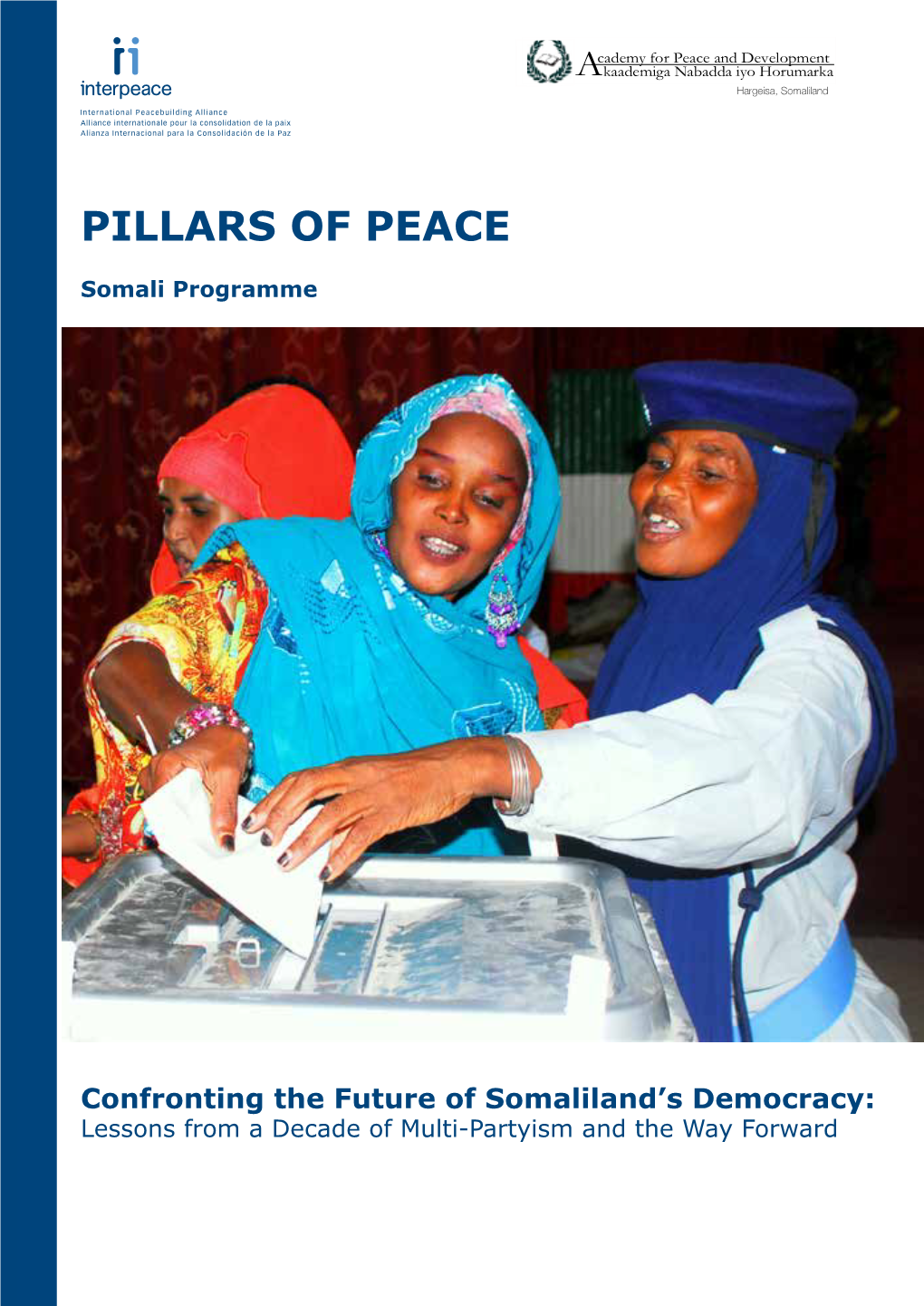

Election Results: Complications and Achievements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti

Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti DISSERTATION ZUR ERLANGUNG DER GRADES DES DOKTORS DER PHILOSOPHIE DER UNIVERSTÄT HAMBURG VORGELEGT VON YASIN MOHAMMED YASIN from Assab, Ethiopia HAMBURG 2010 ii Regional Dynamics of Inter-ethnic Conflicts in the Horn of Africa: An Analysis of the Afar-Somali Conflict in Ethiopia and Djibouti by Yasin Mohammed Yasin Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (POLITICAL SCIENCE) in the FACULITY OF BUSINESS, ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES at the UNIVERSITY OF HAMBURG Supervisors Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff HAMBURG 15 December 2010 iii Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank my doctoral fathers Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit and Prof. Dr. Rainer Tetzlaff for their critical comments and kindly encouragement that made it possible for me to complete this PhD project. Particularly, Prof. Jakobeit’s invaluable assistance whenever I needed and his academic follow-up enabled me to carry out the work successfully. I therefore ask Prof. Dr. Cord Jakobeit to accept my sincere thanks. I am also grateful to Prof. Dr. Klaus Mummenhoff and the association, Verein zur Förderung äthiopischer Schüler und Studenten e. V., Osnabruck , for the enthusiastic morale and financial support offered to me in my stay in Hamburg as well as during routine travels between Addis and Hamburg. I also owe much to Dr. Wolbert Smidt for his friendly and academic guidance throughout the research and writing of this dissertation. Special thanks are reserved to the Department of Social Sciences at the University of Hamburg and the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) that provided me comfortable environment during my research work in Hamburg. -

September 29, 2005 Parliamentary Election Assessment Report

International Republican Institute Suite 700 1225 Eye St., NW Washington, D.C. 20005 (202) 408-9450 (202) 408-9462 FAX www.iri.org International Republican Institute Somaliland September 29, 2005 Parliamentary Election Assessment Report Table of Contents Map of Somaliland……………………………………………………………………..….2 Executive Summary…………………………………………………………………….....3 I. Background Information.............................................................................................…..5 II. Legal and Administrative Framework………………………………..………..……….8 III. Pre-Election Period……………. …...……………………………..…………...........12 IV. Election Day…………...…………………………………………………………….18 V. Post-Election Period and Results.…………………………………………………….27 VI. Findings and Recommendations……………………………………………………..33 VII. Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………..38 Appendix A: Voting Results in 2005 Presidential Elections…………………………….39 Appendix B: Voting Results in 2003 Presidential Elections…………………………….41 Appendix C: Voting Results in 2002 Local Government Elections……………………..43 Appendix D: Voting Trends……………………………………………………………..44 IRI – Somaliland September 29, 2005 Parliamentary Election Assessment Report 1 Map of Somaliland IRI – Somaliland September 29, 2005 Parliamentary Election Assessment Report 2 Executive Summary Background The International Republican Institute (IRI) has conducted programs in Somaliland since 2002 with the support of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), the U.S. Department of State, and the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). IRI’s Somaliland -

SOMALILAND GENDER GAP ASSESSMENT March 2019 Acknowledgements

SOMALILAND GENDER GAP ASSESSMENT March 2019 Acknowledgements Many organisations and individuals gave crucial cooperation in the implementation of this research. The research team would like to extend their appreciation to those who volunteered their time to participate in various capacities, particularly interviewees and focus group discussion participants. This report is a production of and attributable to NAGAAD, with Oxfam providing funding and technical support and Forcier Consulting implementing the research. Thank you to the staff from each organisation involved in the production of this report. Contact: NAGAAD, Hargeisa, Somaliland. [email protected] www.nagaad.org This report is not a legally binding document. It is a collaborative informational and assessment document and does not necessarily reflect the views of any of the contributing organisations or funding agencies in all of its contents. Any errors are the sole responsibility of the authors. Supported by: CONTENTS Acronyms 4 1. Executive Summary: The Gender Gap at a Glance 5 2. Recommendations 9 3. Introduction 11 4. Indicators for Composite Gender Gap Index 12 5. Limitations 13 6. Research Findings 14 6.1 Economic Participation 14 6.2 Economic Opportunity 19 6.3 Political Empowerment 31 6.4 Educational Attainment 37 7. Conclusion 50 8. Technical Annex 51 8.1 Methodological Framework 51 8.2 Index Calculation 52 ACRONYMS ABE Alternative Basic Education CATI Computer-Assisted Telephone Interviews FGD Focus Group Discussion HAVOYOCO Horn of Africa Voluntary Youth Committee -

Understanding Household Responses to Food Insecurity and Famine Conditions in Rural Somaliland

Understanding Household Responses to Food Insecurity and Famine Conditions in Rural Somaliland By Ismail Ibrahim Ahmed A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of London Wye College University of London December 1994 ProQuest Number: 11010333 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11010333 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 / ' " V ' .• •‘W^> / a - ; "n ^T.k:, raj V£\ aK ^ 's a ABSTRACT This thesis examines the responses adopted by rural households in Somaliland to changes in their resource endowments and market exchange during the 1988- 1992 food crisis. It tests whether there is a predictable sequence of responses adopted by rural households when faced with food insecurity and famine conditions and examines the implications of this for famine early warning and famine response. The research is based on fieldwork conducted in rural Somaliland in 1992. A sample of 100 households interviewed just before the outbreak of the war in 1987 were re-sampled, allowing comparisons to be made before and after the crisis. -

Briefing Paper

NEW ISSUES IN REFUGEE RESEARCH Working Paper No. 65 Pastoral society and transnational refugees: population movements in Somaliland and eastern Ethiopia 1988 - 2000 Guido Ambroso UNHCR Brussels E-mail : [email protected] August 2002 Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit Evaluation and Policy Analysis Unit United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees CP 2500, 1211 Geneva 2 Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] Web Site: www.unhcr.org These working papers provide a means for UNHCR staff, consultants, interns and associates to publish the preliminary results of their research on refugee-related issues. The papers do not represent the official views of UNHCR. They are also available online under ‘publications’ at <www.unhcr.org>. ISSN 1020-7473 Introduction The classical definition of refugee contained in the 1951 Refugee Convention was ill- suited to the majority of African refugees, who started fleeing in large numbers in the 1960s and 1970s. These refugees were by and large not the victims of state persecution, but of civil wars and the collapse of law and order. Hence the 1969 OAU Refugee Convention expanded the definition of “refugee” to include these reasons for flight. Furthermore, the refugee-dissidents of the 1950s fled mainly as individuals or in small family groups and underwent individual refugee status determination: in-depth interviews to determine their eligibility to refugee status according to the criteria set out in the Convention. The mass refugee movements that took place in Africa made this approach impractical. As a result, refugee status was granted on a prima facie basis, that is with only a very summary interview or often simply with registration - in its most basic form just the name of the head of family and the family size.1 In the Somali context the implementation of this approach has proved problematic. -

Territorial Diagnostic Report of the Land Resources of Somaliland

Territorial diagnostic report of the land resources of Somaliland Technincal Report No. L-21 February, 2016 Somalia Water and Land Information Management Ngecha Road, Lake View. P.O Box 30470-00100, Nairobi, Kenya. Tel +254 020 4000300 - Fax +254 020 4000333, Email: [email protected] Website: http//www.faoswalim.org Funded by the European Union and implemented by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 1 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the SWALIM Project concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries This document should be cited as follows: Ullah, Saleem, 2016. Territorial diagnostic report of the land resources of Somaliland. FAO-SWALIM, Nairobi, Kenya. 2 Table of Contents List of Acronyms .......................................................................................................................... 7 Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................................ 9 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... 10 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 16 1.1 Background -

CLAIMING the EASTERN BORDERLANDS After the 1997

CHAPTER SEVEN CLAIMING THE EASTERN BORDERLANDS After the 1997 Hargeysa Conference, the Somaliland state apparatus consolidated. It deepened, as the state realm displaced governance arrangements overseen by clan elders. And it broadened, as central government control extended geographically from the capital into urban centres such as Borama in the west and Bur’o in the east. In the areas east of Bur’o government was far less present or efffective, especially where non-Isaaq clans traditionally lived. Erigavo, the capital of Sanaag Region, which was shared by the Habar Yunis, the Habar Ja’lo, the Warsengeli and the Dhulbahante, was fijinally brought under formal government control in 1997, after Egal sent a delegation of nine govern- ment ministers originating from the area to sort out local government with the elders and political actors on the ground. After fijive months of negotiations, the president was able to appoint a Mayor for Erigavo and a Governor for Sanaag.1 But east of Erigavo, in the area inhabited by the Warsengeli, any claim to governance from Hargeysa was just nominal.2 The same was true for most of Sool Region inhabited by the Dhulbahante. Eastern Sanaag and Sool had not been Egal’s priority. The president did not strictly need these regions to be under his military control in order to preserve and consolidate his position politically or in terms of resources. The port of Berbera was vital for the economic survival of the Somaliland government. Erigavo and Las Anod were not. However, because the Somaliland government claimed the borders of the former British protec- torate as the borders of Somaliland, Sanaag and Sool had to be seen as under government control. -

Somali Fisheries

www.securefisheries.org SECURING SOMALI FISHERIES Sarah M. Glaser Paige M. Roberts Robert H. Mazurek Kaija J. Hurlburt Liza Kane-Hartnett Securing Somali Fisheries | i SECURING SOMALI FISHERIES Sarah M. Glaser Paige M. Roberts Robert H. Mazurek Kaija J. Hurlburt Liza Kane-Hartnett Contributors: Ashley Wilson, Timothy Davies, and Robert Arthur (MRAG, London) Graphics: Timothy Schommer and Andrea Jovanovic Please send comments and questions to: Sarah M. Glaser, PhD Research Associate, Secure Fisheries One Earth Future Foundation +1 720 214 4425 [email protected] Please cite this document as: Glaser SM, Roberts PM, Mazurek RH, Hurlburt KJ, and Kane-Hartnett L (2015) Securing Somali Fisheries. Denver, CO: One Earth Future Foundation. DOI: 10.18289/OEF.2015.001 Secure Fisheries is a program of the One Earth Future Foundation Cover Photo: Shakila Sadik Hashim at Alla Aamin fishing company in Berbera, Jean-Pierre Larroque. ii | Securing Somali Fisheries TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES, TABLES, BOXES ............................................................................................. iii FOUNDER’S LETTER .................................................................................................................... v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................. vi DEDICATION ............................................................................................................................ vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY (Somali) ............................................................................................ -

Somaliland Assistance Bulletin

Somaliland Assistance Bulletin 1 – 30 November 2005 HUMANITARIAN SITUATION Security & Access The overall security situation in Somaliland remained stable. A verdict was issued on the trail case of the 10 arrested suspects of the killings of four humanitarian workers occurring in 2003 and 2004. The case originally started in March 2005. According to the regional court in Hargeisa, 8 men were found guilty of "terrorism" and were sentenced to death. Following the killing of the 4 expatriate humanitarian workers, the UN in collaboration with the national authorities established a Special Protection Unit (SPU) initially to provide protection for humanitarian workers of UN & international NGOs, subsequently extended to the rest of the community. Since then no further incidents were reported. A deadly mine accident occurred in Burao on 16 November 2005 where a vehicle diverted from the main road towards a roadside short cut. Three out of a total of seven passengers were reported dead, including one UN staff member. Somaliland Mine Action Center (SMAC), supported by UNDP, coordinates mine action activities, since late 1999, an approximate area of around 115 million square meters has been cleared. Food Security/Livelihoods Aerial Photograph of Burao settlements, source UN Habitat. Deyr rain started on time, whereby most areas received Ministry of Health & Labour (MOH&L), the Somali Red normal to above normal rains except for parts of Crescent Society, Save the Children Fund, Candlelight southern Awdal region. Rainfall distribution and intensity and Havoyoco. Sources of income among Burao were good and allowed for further replenishment of water settlements were labeled more irregular and unreliable. -

From Somalia

Home > Research > Responses to Information Requests RESPONSES TO INFORMATION REQUESTS (RIRs) New Search | About RIRs | Help 25 November 2011 SOM103870.E Somalia: Somaliland, including government structure, security, and access for internally displaced persons (IDPs) from Somalia Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Ottawa Somaliland, located in the northwest of Somalia, is a self-declared independent republic (The Europa World Year Book 2011; Human Rights Watch 2011). It officially seceded from Somalia in 1991, but has not been recognized by the international community (MRG 2010, 17; The Guardian 26 Aug. 2011). Government and Administration Somaliland has a directly elected president and a bicameral legislature (US 8 Apr. 2011 Sec. 3; Human Rights Watch July 2009, 16-17) comprised of a house of representatives and a house of elders (ibid.; ACCORD Dec. 2009, 5). Its 2010 presidential elections were deemed to be generally free and fair by international observers (Human Rights Watch 2011; US 8 Apr. 2011, Sec. 3). The United States (US) Department of State notes that while the 2002 Somaliland constitution is based on democratic principles, the region also uses laws enacted prior to 1991, and does not recognize Somalia's Transitional Federal Charter (ibid., Sec.1.e). Somaliland's administrative institutions are considered to be generally functional (ibid., Sec. 3; ACCORD Dec. 2009, 5; The Guardian 26 Aug. 2011). However, sources also note that the government's limited revenue, due in part to its ineligibility for international development assistance as an unrecognized sovereign state, limits its ability to provide basic public services (ibid.; Human Rights Watch July 2009, 12; Freedom House 2011). -

Somaliland – a Walk on Thin Ice 1

7|2011 KAS INTERNATIONAL REPORTS 79 SOMALILAND – A WALK ON THIN ICE 1 Harriet Gorka “Northerners can in no way claim that the 1960 merger with the South was a shotgun wedding – by all accounts unification was wildly popular. Northerners could argue, however, that they asked for an annulment of the union prior to the honeymoon and that their request was unjustly denied.”2 This statement by a legal scholar reflects the prevailing balancing act of the conflict in Somaliland, which some might say started with the voluntary unification of Harriet Gorka worked Somaliland and the Italian Trust Territory of Somalia. Yet from February to April 2011 at the Konrad- the conflict goes deeper and is more far reaching than Adenauer-Stiftung in “just” the desire to secede from the Somali state. It is Windhoek, Namibia. an ongoing debate whether the right to self-determination should prevail over the notions of territorial integrity and sovereignty. May 2011 marked the 20-year anniversary of Somaliland’s proclamation of independence. However, its status has not officially been recognised by any state, even though it has a working constitutional government, an army, a national flag and its own currency, which should make Somaliland a stand out example for other entities seeking independence. The territory also sets itself apart from the rest of Somalia because it is stable and peaceful, which has been achieved by integrating clan culture into its government. The accom- plishments of the past two decades are impressive, despite 1 | The opinion expressed by the author is not in all points similar to the opinion of the editors. -

Rethinking the Somali State

Rethinking the Somali State MPP Professional Paper In Partial Fulfillment of the Master of Public Policy Degree Requirements The Hubert H. Humphrey School of Public Affairs The University of Minnesota Aman H.D. Obsiye May 2017 Signature below of Paper Supervisor certifies successful completion of oral presentation and completion of final written version: _________________________________ ____________________ ___________________ Dr. Mary Curtin, Diplomat in Residence Date, oral presentation Date, paper completion Paper Supervisor ________________________________________ ___________________ Steven Andreasen, Lecturer Date Second Committee Member Signature of Second Committee Member, certifying successful completion of professional paper Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 3 Methodology .......................................................................................................................... 5 The Somali Clan System .......................................................................................................... 6 The Colonial Era ..................................................................................................................... 9 British Somaliland Protectorate ................................................................................................. 9 Somalia Italiana and the United Nations Trusteeship .............................................................. 14 Colonial