Revisiting the Wackernagelposition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Allegato a Annesso Alla Legge 28 Dicembre 2001, N

ALLEGATO “A” . COMUNE DI LUSIANA CONCO Provincia di Vicenza D.U.P.: DOCUMENTO UNICO DI PROGRAMMAZIONE /NOTA DI AGGIORNAMENTO 2020-2021-2022 1 ALLEGATO “A” QUADRO GENERALE DEL NUOVO COMUNE DI LUSIANA CONCO Il Comune di Lusiana Conco è collocato territorialmente nella fascia meridionale dell’Altopiano dei Sette Comuni, la particolare conformazione morfologica e la posizione ai margini della pianura sono i due principali elementi che hanno delineato i caratteri identitari e determinato lo sviluppo socioeconomico del territorio. Il popolamento dell’area sud dell’Altopiano trae origine dall’antica migrazione delle genti bavaresi e dallo spostamento di popolazioni di origine veneta, essenzialmente per motivazioni di natura economica, legate alla possibilità di praticare l’allevamento, la pastorizia, l’agricoltura, l’artigianato , utilizzando le risorse dell’ambiente e i contatti con la pianura. L’appartenenza alla Reggenza dei Sette Comuni sin dall’inizio della sua costituzione (1310) per Lusiana, più tardi come “Contrade Annesse” per Conco, garantì il mantenimento delle leggi comunitarie e di altre forme di autonomia che trovano riscontro ancora oggi nella stessa gestione dei boschi e dei pascoli. Il territorio comunale si estende su 61,19 km² (di questi, 34,34 km² appartenevano all'ex comune di Lusiana e 26,85 km² all'ex comune di Conco). La quota minima è di 229 m (presso Laverda), mentre la massima è di 1388 m (monte Gusella o Mosca). Nel demanio di uso civico ex Comune di Lusiana ma territorio amministrativo (censuario) di Asiago si trova Cima XII che con i suoi 2336 m la montagna più alta della provincia e di tutte le prealpi vicentine. -

Roana E Rotzo

Territori e contrade di Roana e Rotzo, Altopiano dei Sette Comuni In allen de lentlen Robaan un Rotz, Hooga Ebene bon Siben Komoine 12 22 luglio hùbiot 2018 Boolkhènt au in de Hooga Ebene bon Siben Komoine PATROCINIO Provincia Comune Comune Istituto di Cultura Associazioni Pro Loco Boolkhènt in de Hoga Zait! REGIONE DEL VENETO di Vicenza di Roana di Rotzo Cimbra del Comune di Roana Benvenuti sull’Altopiano dei Sette Comuni. Benvenuti in Hoga Zait! Letteralmente Hoga Zait significa “tempo alto”, “tempo bello” e, quindi, tempo di festa. Camporovere Hoga Zait è la festa dei Cimbri. Kamparube Ghéebar metanandar! La Schella indica Mezzaselva dove si svolgono Toballe gli eventi Il Sindaco Valentino Frigo e l’Amministrazione Ci sarà musica! Comunale di Roana Roana Robaan Per i più piccoli Canove Roan Per tutta la famiglia Rotzo Rotz Appuntamento culturale Cesuna Kan-Züne È indispensabile Treschè Conca calzare scarpe Kunka da trekking Si suppone che il graffito Schella o da ginnastica preistorico della Val d’Assa a “microcoppelle” e Schellaträgar potesse rappresentare una mappa; per questo motivo Gli Schellaträgar, ha ispirato il sistema di rappresentazione rappresentanti delle sei frazioni toponomastica e custodi della campana, del territorio utilizzato per questo libretto diventano ambasciatori cimbri oltre che per il sistema con il compito di dare il benvenuto di identità visiva del Comune di Roana agli ospiti dal mondo. Hoga Zait 2018: L’abito degli Schellaträgar: tradizione del territorio e identità lo studio per il nuovo costume Dal 2006 anni questa Amministrazione, nell’ambito delle iniziative proposte Per l’edizione 2018 di Hoga Zait dall’Assessorato al Turismo e Cultura, organizza Hoga Zait - Il Festival Cimbro®, si è voluto approfondire l’aspetto nell’intenzione di proseguire una manifestazione che coinvolge tutta del costume tipico dell’Altopiano la popolazione, sia turista che residente. -

Allegato “A” NUOVA FORMULAZIONE DI N. 2 SCHEDE IDENTIFICATIVE DELLE TIPOLOGIA DI PROGETTO OGGETTO DELL’ATTO AGGIUNTIVO

Parte integrante e sostanziale dello schema del primo atto aggiuntivo di cui all’ALLEGATO 2 alla deliberazione del Comitato paritetico n. 7 del 14 marzo 2018 Schema del Primo atto aggiuntivo alla convenzione di cui all’Articolo 4,comma 1, Punti c) ed e) del Regolamento del Comitato Paritetico per la gestione dell’Intesa avente ad oggetto “Attuazione della proposta di Programma di interventi strategici limitatamente al primo stralcio per gli interventi denominati “Progetto strategico di ammodernamento e sviluppo infrastrutturale per la mobilità turistica invernale ed estiva dell’Altopiano di Asiago (VI) – Area “Larici – Val Formica”” e “Interventi di ammodernamento e completamento dei comprensori sciistici dell’Altopiano di Asiago – Monte Verena” nel territorio della provincia di Vicenza” Allegato “A” NUOVA FORMULAZIONE DI N. 2 SCHEDE IDENTIFICATIVE DELLE TIPOLOGIA DI PROGETTO OGGETTO DELL’ATTO AGGIUNTIVO IL PRESIDENTE DEL COMITATO PARITETICO IL PRESIDENTE PER LA GESTIONE DELL'INTESA PER DELLA REGIONE DEL VENETO IL FONDO COMUNI DI CONFINE - ______________ - - On. Roger De Menech - PAT/RFD336-20/02/2018-0106714 - Allegato Utente 3 (A03) A. DENOMINAZIONE DEL PROGETTO STRATEGICO PROGETTO STRATEGICO DI AMMODERNAMENTO E SVILUPPO INFRASTRUTTURALE PER LA MOBILITA’ TURISTICA INVERNALE ED ESTIVA DELL’ALTOPIANO DI ASIAGO (VI) – AREA “ LARICI –VAL FORMICA ” B. SOGGETTO/I PROPONENTE/I (Art. 7 Linee guida) Comune di Rotzo – Comune di Roana – Comune di Lusiana (Comune Capofila) C. CRITICITÀ CHE HANNO PORTATO ALL’INDIVIDUAZIONE DEL PROGETTO (descrizione sommaria , massimo 500 caratteri) - Necessità di completare, con sostituzione della vecchia sciovia “Cima Larici” inattiva per fine vita tecnica con una nuova seggiovia quadriposto, la dotazione impiantistica funiviaria dell’importante stazione turistica estiva ed invernale di Val Formica – Cima Larici, sorta nell’anno 1966 e da qualche anno soggetta ad importanti interventi di riqualificazione ed ammodernamento per iniziativa pubblica e privata . -

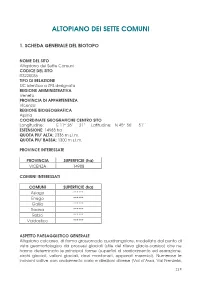

Altopiano Dei Sette Comuni

ALTOPIANO DEI SETTE COMUNI 1. SCHEDA GENERALE DEL BIOTOPO NOME DEL SITO Altopiano dei Sette Comuni CODICE DEL SITO IT3220036 TIPO DI RELAZIONE SIC identico a ZPS designata REGIONE AMMINISTRATIVA Veneto PROVINCIA DI APPARTENENZA Vicenza REGIONE BIOGEOGRAFICA Alpina COORDINATE GEOGRAFICHE CENTRO SITO Longitudine: E 11° 26’ 21” Latitudine: N 45° 56’ 51’’ ESTENSIONE: 14988 ha QUOTA PIU’ ALTA: 2336 m s.l.m. QUOTA PIU’ BASSA: 1300 m s.l.m. PROVINCE INTERESSATE PROVINCIA SUPERFICIE (ha) VICENZA 14988 COMUNI INTERESSATI COMUNI SUPERFICIE (ha) Asiago ****** Enego ****** Gallio ****** Roana ****** Rotzo ****** Valdastico ****** ASPETTO PAESAGGISTICO GENERALE Altopiano calcareo, di forma grossomodo quadrangolare, modellato dal punto di vista geomorfologico da processi glaciali (stile del rilievo glacio-carsico) che ne hanno determinato le principali forme (superfici di sradicamento ed esarazione, circhi glaciali, valloni glaciali, dossi montonati, apparati morenici). Numerose le incisioni vallive con andamento vario e direzioni diverse (Val d’Assa, Val Frenzela, 215 Val Gadena). A causa della natura eminentemente permeabile del substrato geologico, mancano quasi completamente i corsi d’acqua superficiali. Diversi i fenomeni carsici rilevabili nell’area. La vegetazione è differenziata a seconda della quota e della tipologia del substrato. Sono presenti formazioni boschive miste (bosco misto) nell’orizzonte collinare sub-montano. Le faggete sono diffuse soprattutto nell’orizzonte montano inferiore a quote comprese tra i 1000 e 1300 m e comunque quasi mai in formazioni pure ma consociate al Peccio. La pecceta caratterizza quasi per intero l’orizzonte montano superiore (formazioni miste con abete bianco nelle aree più umide) mentre i lariceti si rinvengono sporadicamente a quote più elevate (1650-1850 m). -

Formaggio Malga Dell'altopiano Dei Sette

Atlante dei prodotti agroalimentari tradizionali del Veneto FORMAGGI FORMAGGIO MALGA DELL’ALTOPIANO DEI SETTE COMUNI Eventuali sinonimi e termini dialettali dopo 6 mesi (allevo mezzano), stagionato pronto buendo sopra del sale a secco. Rivoltate e salate Formaggio malga Altopiano dei Sette Comuni, al- dopo 1 anno (allevo vecchio) o 1 anno e mezzo, 2 per 6-7 giorni, le forme si portano poi nel reparto levo di malga. anni (allevo stravecchio). di stagionatura dove rimangono per un anno o due La pasta è dura, con occhiatura piccola e sparsa a seconda del tipo di formaggio che si vuole otte- detta ad “occhio di pernice” che tende a ridursi nere. mano a mano che la stagionatura procede e la for- ma perde fi no ad un quarto del proprio peso. Usi La crosta si presenta liscia e regolare di colore gial- L’allevo di malga viene utilizzato solitamente come lo paglierino che scurisce con la maturazione. Le formaggio di fi ne pasto e usualmente si accompa- dimensioni variano in altezza dai 9 ai 12 cm e in gna con la polenta, morbida o abbrustolita. peso dai 7 ai 9 kg; il diametro varia dai 30 ai 36 cm. Al tatto la pasta si presenta compatta e leggermen- Reperibilità te untuosa, all’olfatto si ha un’intensa sensazione Nelle malghe dell’Altopiano e presso i rivenditori di fi ori amari, spezie, timo e fi eno secco. della zona, è reperibile durante tutto l’anno. Processo di produzione Territorio interessato alla produzione Il latte munto della sera viene fi ltrato, lasciato ripo- Sette Comuni dell’altopiano di Asiago, in particola- sare tutte la notte in vasche di acciaio e al mattino re Gallio, Rotzo, Conco, Lusiana, Enego in provin- successivo la panna formatasi viene tolta. -

2° RADUNO SEZIONI DEL VENETO ASIAGO E ALTOPIANO DEI SETTE COMUNI (VI)

CLUB ALPINO ITALIANO REGIONE DEL VENETO 2° RADUNO SEZIONI DEL VENETO 17 SETTEMBRE 2017 ASIAGO e ALTOPIANO DEI SETTE COMUNI (VI) Breve guida con descrizione dei 10 percorsi proposti 1 INQUADRAMENTO TERRITORIALE L’ambito del Piano di Area dell’Altopiano dei Sette Comuni, dei costi e delle colline pedemontane vicentine comprende il territorio dell’Altopiano dei Sette Comuni, i versanti sud-ovest (fino a 600 m. s.l.m.) con la fascia dei costi e delle colline di Marostica e Bassano, e ad est il versante della destra Brenta. L’ambito del Piano di Area sorge nella parte settentrionale della Provincia di Vicenza, confinando a nord con il Trentino-Alto Adige. L’Altopiano è coronato a nord da una linea di cresta, le cui cime arrivano a superare i 2300 m., mentre verso sud è delimitato da una dorsale con quote comprese tra i 1000 e i 1400 m.; al centro si trova una fascia morfologicamente depressa, allungata in senso est-ovest, con altitudine media intorno ai 1000 m., che accoglie i maggiori centri abitati: Rotzo, Roana, Canove, Asiago, Gallio, Foza e d Enego. L’Altopiano risulta nettamente isolato a causa delle profonde incisioni vallive che lo separano dalle vicine aree montuose: a nord la Valsugana e a est il Canale del Brenta, a ovest il tratto il tratto meridionale della Val d’Astico e la Val Torra; solo verso sud è presente una scarpata di raccordo alle colline pedemontane che consente un acceso relativamente facile all’Altopiano. Per contro le scarpate che scendono al fondo delle valli citate sono molto rapide, spesso caratterizzate da pareti strapiombanti; qui l’erosione ha messo a nudo la sequenza degli strati rocciosi che compongono il corpo dell’Altopiano, consentendo di ricostruire la storia geologica. -

“La Reggenza Dei Sette Comuni”. I Primi Documenti Che Citano I

SOCIETA’ ED ECONOMIA PREMESSA STORICA “La Reggenza dei Sette Comuni”. I primi documenti che citano i “Sette Comuni” li troviamo agli inizi del XIV secolo. In particolare, una pergamena del 1339 (conservata presso la biblioteca Bertoliana) evidenzia l’unità politica raggiunta dall’insieme delo Sette Comuni allocrchè richiesero agli Scaligeri, ottenendola, l’indipendenza da Vicenza, l‘autonomia politico-amministrativa e totale esenzione fiscale. L’organo politico che governava questo territorio fu, nel tempo, battezzato “Reggenza dei Sette Comuni”. Si trattava di una piccola Repubblica (467 kmq – oltre il 20% della Provincia di Vicenza - e circa sette volte più estesa di San Marino il cui Governatore, guardacaso, era chiamato “Reggente”), con una storia che durò cinque secoli, caratterizzati da un’amministrazione che scaturiva dalla democrazia diretta, (fondata sulle vicinie, cioè le assemblee dei capifamiglia) e da una politica estera volta a salvaguardare l’economia del territorio e la propria autonomia. Anche l’economia si esprimeva con la medesima modalità di governo: democrazia e proprietà e/o diritti sulla proprietà dei beni silvo pastorali di natura societaria/collettiva; un collettivismo che conviveva con la proprietà privata delle fattorie adiacenti i singoli villaggi. Le comunità costituivano quelle che potrebbero essere definite delle società proto- cooperative. La forma espressiva, come accennato, era costituita dalla vicinia, ovvero dall’assemblea dei capifamiglia intesi come “capi di casa”, chiamata a decidere sul bene comune e sui beni collettivi nonchè sulla nomina dei procuratori abilitati a trattare talora singoli affari e a garantire la diligente cura degli affari correnti. I „vicini-proprietari“ votavano esclusivamente „per testa“; era ammessa la delega di voto (ad un familiare) e l’assemblea regolamentava l’uso die beni silvo pastoriali: appunto, all’incirca come avviene oggi nelle moderne società cooperative. -

“I Territori Della Montagna”

approfondimento tematico “I Territori della Montagna” Allegato alla Relazione del PTCP Piano Territoriale Coordinamento Provinciale Ufficio di Piano INDICE INTRODUZIONE.............................................................................................................. 4 QUADRO DI RIFERIMENTO ISTITUZIONALE E NORMATIVO ........................................ 5 Disposizioni normative emanate dalla Comunità Europea........................................ 5 Normativa nazionale................................................................................................... 6 Normativa regionale................................................................................................... 8 Piano territoriale regionale di coordinamento................................................................... 11 LE MONTAGNE VICENTINE......................................................................................... 13 Ambito n. 1 - Il sistema del Pasubio e delle Piccole Dolomiti ................................. 14 Sistema insediativo................................................................................................... 14 Servizi alla popolazione residente.............................................................................. 14 Servizi alla popolazione residente.............................................................................. 15 Sistema della mobilità................................................................................................ 16 Sistema ambientale.................................................................................................. -

ASIAGO a Cura Di G

1 NOTE ILLUSTRATIVE della CARTA GEOLOGICA D’ITALIA alla scala 1:50.000 foglio 082 ASIAGO a cura di G. Barbieri1, P. Grandesso1 con i contributi di Geologia del Substrato V. De Zanche1, P. Gianolla2, G. Roghi3, D. Zampieri1, A. Zanferrari4 Geologia del Quaternario M. Cucato1 Aspetti applicativi W. Del Piero5, P. Mietto1, E. Schiavon5 PROGETTO1 Analisi biostratigrafiche P. Grandesso Analisi petrografiche C. Stefani1, D. Visonà6 1 Dipartimento di Geologia, Paleontologia e Geofisica, Università degli Studi di Padova 2 Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Università degli Studi di Ferrara 3 Istituto di Geoscienze e Georisorse, CNR, Padova 4 Dipartimento Georisorse e Territorio, Università degli Studi di Udine 5 Regione del Veneto - Direzione Geologia e Attività Estrattive 6 Dipartimento di Mineralogia e Petrologia, Università degli StudiCARG di Padova 2 Direttore del Dipartimento Difesa del Suolo - Servizio Geologico d’Italia: L. Serva Responsabile del Progetto CARG per il Dipartimento Difesa del Suolo - Servizio Geologico d’Italia: F. Galluzzo Responsabile del Progetto CARG per la Regione del Veneto: F. Toffoletto PER IL DIPARTIMENTO DIFESA D EL SUOLO - SERVIZIO GEOLO G ICO D’ITALIA : Revisione scientifica: M. Pantaloni (coordinatore), R. Graciotti, M.L. Pampaloni Coordinamento cartografico: D. Tacchia (coordinatore), S. Falcetti Revisione informatizzazione dei dati geologici: L. Battaglini, C. Cipollini, D. Delogu, M.C. Giovagnoli (ASC) Coordinamento editoriale e allestimento per la stampa: M. Cosci, S. Falcetti PER LA RE G IONE D EL VENETO : Allestimento editoriale e cartografico: R. Campana Allestimento informatizzazione dei dati geologici: R. Campana (responsabile), V. Perna, R. Campana (direzione lavori), R. Campana (collaudo) Informatizzazione e allestimento cartografico per la stampa dalla Banca Dati a cura della S.EL.CA.PROGETTO s.r.l., Firenze Gestione tecnico-amministrativa del Progetto CARG: M.T. -

Unità Di Apprendimento “Viaggio Nel Bosco”

Unità di apprendimento “Viaggio nel bosco” Classe 1^F Anno scolastico 2018/19 Enego 2 27 Era la sera del 29 ottobre quando il nostro Altopiano è stato sconvolto da un Enego, un po’ di storia…. evento che nessuno avrebbe potuto immaginare. Il vento, a più di 150 Km/h, ha raso al suolo i nostri boschi. Enego è sempre stato un luogo strategico. Marcesina, zona bellissima e invidiata da tutti, con alberi maestosi, prati lus- ETÀ PREROMANA sureggianti e malghe, è diventata irriconoscibile. Questo evento ha turbato I primi insediamenti umani, sull’Altopiano, risalgono al mesolitico dal tutti! 10.000 all’8.000 a.C.; il Bostel costituisce uno dei primi insediamenti. I Guardando ora il bosco, sembra che qualcuno , con molta cura, abbia allinea- Veneti si stabilirono in questo territorio nel I a.C.. to gli alberi sul suolo. ETÀ ROMANA Si dice che i danni siano paragonabili alla distruzione avvenuta durante la Enego è stato anche un avamposto romano, i romani costruirono, in Grande Guerra. E’ stato stimato, infatti, che sono stati schiantati circa località Bastia, un torrione che serviva a controllare la Valsugana. La 300.000 alberi, il 10% del patrimoni boschivo dell’Altopiano! Valsugana era un’ importante via di scambio tra l’attuale Germania e Tutto questo è accaduto perché il vento proveniente dal mar Mediterraneo si l’Italia. I Romani avevano costruito degli edifici dove si trova oggi il cen- è surriscaldato, a causa del cambiamento climatico, e si è incontrato con quel- tro di Enego, avevano costruito un tempio dedicato alla dea Diana. -

Relazione Tecnica

Regione del Veneto Comune di Lusiana Provincia di Vicenza PIANO DI ASSETTO DEL TERRITORIO (PAT) Legge regionale 23 aprile 2004, n. 11 "Norme per il governo del territorio" RELAZIONE TECNICA Relazione tecnica che espone gli esiti delle analisi, della concertazione e delle verifiche territoriali, necessarie per la valutazione di sostenibilità ambientale e territoriale (L.R. n. 11/2004, Art. 13 e D.G.R. n. 3178/2004, lett. g) 2 _______________________________________________________________________________________________ Dalla Torre.Fantin.Pellizzer Architetti Pianificatori Associati via A. Nonis, 18 - 36063 Marostica - tel. e fax 0424 780958 Regione del Veneto Comune di Lusiana Provincia di Vicenza PIANO DI ASSETTO DEL TERRITORIO (PAT) Legge regionale 23 aprile 2004, n. 11 "Norme per il governo del territorio" RELAZIONE TECNICA Indice 1. Esiti delle analisi 1.1. Nuova Legge Urbanistica Regionale: contenuti, finalità e obiettivi 1.2. Scelte strategiche e obiettivi di sostenibilità del piano 1.3. Lo stato attuale dell’ambiente in Comune di Lusiana 1.3.1. Inquadramento del territorio comunale 1.3.1.1. Il sistema insediativo del Comune di Lusiana. Evoluzione storica 1.3.2. Il Quadro Conoscitivo e la raccolta dei dati 1.3.2.1. Componente aria 1.3.2.2. Componente clima 1.3.2.3. Componente acqua 1.3.2.4. Componente suolo e sottosuolo 1.3.2.5. Componente agenti fisici 1.3.2.5.1. Rumore 1.3.2.5.2. Inquinamento luminoso 1.3.2.5.3. Campi elettromagnetici 1.3.2.5.4. Radon 1.3.2.6. Componente biodiversità, flora e fauna 1.3.2.6.1. Descrizione del Sito di Importanza Comunitaria (SIC) “Granezza” 1.3.2.7. -

Roana Pro Loco Roana T

siago omuni ITAAEN 7C 4 stagioni 1 altopiano altri punti di informazione IAT turistica asiago gallio Ufficio Turistico SIT di Asiago Ufficio Turistico Gallio T. 0424 447919 T. 0424 462221 roana Pro Loco Roana T. 0424 66047 roana Pro Loco Treschè Conca T. 345 709 5489 IAT di territorio - Chalet turistico Pro Loco Cesuna T. 0424 67064 loc. treschè conca Pro Loco Camporovere T. 347 8061309 T. 0424 694361 Pro Loco Canove T. 0424 692125 Pro Loco Mezzaselva T. 0424 66457 rotzo Pro Loco Rotzo T. 0424 691079 foza Comune di Foza - Promozione turistica T. 0424 443641 enego Ufficio del turismo - Pro Loco di Enego T. 0424 490160 conco Pro Loco Conco T. 392 6723669 lusiana Pro Loco Lusiana T. 0424 406098 Prodotto da: 2 gallio Ufficio Turistico Gallio T. 0424 447919 roana Pro Loco Roana T. 0424 66047 Pro Loco Treschè Conca T. 345 709 5489 enego Pro Loco Cesuna T. 0424 67064 Pro Loco Camporovere T. 347 8061309 Pro Loco Canove T. 0424 692125 foza Stoner Pro Loco Mezzaselva T. 0424 66457 gallio Camporovere rotzo roana Pro Loco Rotzo T. 0424 691079 rotzo asiago Stoccaredo foza Mezzaselva Canove Sasso Comune di Foza - Promozione turistica T. 0424 443641 Treschè enego Conca Cesuna Ufficio del turismo - Pro Loco di Enego T. 0424 490160 conco Rubbio Pro Loco Conco T. 392 6723669 conco Piovene lusiana Rocchette Pro Loco Lusiana T. 0424 406098 lusiana VERONA VICENZA PADOVA MILANO VENEZIA 3 In quale periodo dell’anno volete vivere la montagna? On the Northern reaches of the province of Vicenza, Questa guida vuole presentarvi un territorio che con at about 1000m above sea level, lie the lower alpine i suoi mille metri di altitudine media offre tantissime grasslands of the Plateau of Asiago.