A Biodiversity Profile of Afghanistan in 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review and Updated Checklist of Freshwater Fishes of Iran: Taxonomy, Distribution and Conservation Status

Iran. J. Ichthyol. (March 2017), 4(Suppl. 1): 1–114 Received: October 18, 2016 © 2017 Iranian Society of Ichthyology Accepted: February 30, 2017 P-ISSN: 2383-1561; E-ISSN: 2383-0964 doi: 10.7508/iji.2017 http://www.ijichthyol.org Review and updated checklist of freshwater fishes of Iran: Taxonomy, distribution and conservation status Hamid Reza ESMAEILI1*, Hamidreza MEHRABAN1, Keivan ABBASI2, Yazdan KEIVANY3, Brian W. COAD4 1Ichthyology and Molecular Systematics Research Laboratory, Zoology Section, Department of Biology, College of Sciences, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran 2Inland Waters Aquaculture Research Center. Iranian Fisheries Sciences Research Institute. Agricultural Research, Education and Extension Organization, Bandar Anzali, Iran 3Department of Natural Resources (Fisheries Division), Isfahan University of Technology, Isfahan 84156-83111, Iran 4Canadian Museum of Nature, Ottawa, Ontario, K1P 6P4 Canada *Email: [email protected] Abstract: This checklist aims to reviews and summarize the results of the systematic and zoogeographical research on the Iranian inland ichthyofauna that has been carried out for more than 200 years. Since the work of J.J. Heckel (1846-1849), the number of valid species has increased significantly and the systematic status of many of the species has changed, and reorganization and updating of the published information has become essential. Here we take the opportunity to provide a new and updated checklist of freshwater fishes of Iran based on literature and taxon occurrence data obtained from natural history and new fish collections. This article lists 288 species in 107 genera, 28 families, 22 orders and 3 classes reported from different Iranian basins. However, presence of 23 reported species in Iranian waters needs confirmation by specimens. -

Distribution of Ophiomorus Nuchalis Nilson & Andrén, 1978

All_short_Notes_shorT_NoTE.qxd 08.08.2016 11:01 seite 16 92 shorT NoTE hErPETozoA 29 (1/2) Wien, 30. Juli 2016 shorT NoTE logischen Grabungen (holozän); pp. 76-83. in: distribution of Ophiomorus nuchalis CABElA , A. & G rilliTsCh , h. & T iEdEMANN , F. (Eds.): Atlas zur Verbreitung und Ökologie der Amphibien NilsoN & A NdréN , 1978: und reptilien in Österreich: Auswertung der herpeto - faunistischen datenbank der herpetologischen samm - Current status of knowledge lung des Naturhistorischen Museums in Wien; Wien; (Umweltbundesamt). PUsChNiG , r. (1934): schildkrö - ten bei Klagenfurt.- Carinthia ii, Klagenfurt; 123-124/ The scincid lizard genus Ophio morus 43-44: 95. PUsChNiG , r. (1942): Über das Fortkommen A. M. C. dUMéril & B iBroN , 1839 , is dis - oder Vorkommen der griechischen land schildkröte tributed from southeastern Europe (southern und der europäischen sumpfschildkröte in Kärnten.- Balkans) to northwestern india (sindhian Carinthia ii, Klagenfurt; 132/52: 84-88. sAMPl , h. (1976): Aus der Tierwelt Kärntens. die Kriechtiere deserts) ( ANdErsoN & l EViToN 1966; s iN- oder reptilien; pp. 115-122. in: KAhlEr , F. (Ed.): die dACo & J ErEMčENKo 2008 ) and com prises Natur Kärntens; Vol. 2; Klagenfurt (heyn). sChiNd- 11 species ( BoUlENGEr 1887; ANdEr soN & lEr , M . (2005): die Europäische sumpfschild kröte in EViToN ilsoN NdréN Österreich: Erste Ergebnisse der genetischen Unter - l 1966; N & A 1978; suchungen.- sacalia, stiefern; 7: 38-41. soChU rEK , E. ANdErsoN 1999; KAzEMi et al. 2011). seven (1957): liste der lurche und Kriechtiere Kärntens.- were reported from iran including O. blan - Carinthia ii, Klagenfurt; 147/67: 150-152. fordi BoUlENGEr , 1887, O. brevipes BlAN- KEY Words: reptilia: Testudines: Emydidae: Ford , 1874, O. -

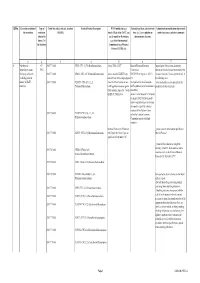

Qrno. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 CP 2903 77 100 0 Cfcl3

QRNo. General description of Type of Tariff line code(s) affected, based on Detailed Product Description WTO Justification (e.g. National legal basis and entry into Administration, modification of previously the restriction restriction HS(2012) Article XX(g) of the GATT, etc.) force (i.e. Law, regulation or notified measures, and other comments (Symbol in and Grounds for Restriction, administrative decision) Annex 2 of e.g., Other International the Decision) Commitments (e.g. Montreal Protocol, CITES, etc) 12 3 4 5 6 7 1 Prohibition to CP 2903 77 100 0 CFCl3 (CFC-11) Trichlorofluoromethane Article XX(h) GATT Board of Eurasian Economic Import/export of these ozone destroying import/export ozone CP-X Commission substances from/to the customs territory of the destroying substances 2903 77 200 0 CF2Cl2 (CFC-12) Dichlorodifluoromethane Article 46 of the EAEU Treaty DECISION on August 16, 2012 N Eurasian Economic Union is permitted only in (excluding goods in dated 29 may 2014 and paragraphs 134 the following cases: transit) (all EAEU 2903 77 300 0 C2F3Cl3 (CFC-113) 1,1,2- 4 and 37 of the Protocol on non- On legal acts in the field of non- _to be used solely as a raw material for the countries) Trichlorotrifluoroethane tariff regulation measures against tariff regulation (as last amended at 2 production of other chemicals; third countries Annex No. 7 to the June 2016) EAEU of 29 May 2014 Annex 1 to the Decision N 134 dated 16 August 2012 Unit list of goods subject to prohibitions or restrictions on import or export by countries- members of the -

The Republic of Tajikistan Ministry of Energy and Industry

The Republic of Tajikistan Ministry of Energy and Industry DATA COLLECTION SURVEY ON THE INSTALLMENT OF SMALL HYDROPOWER STATIONS FOR THE COMMUNITIES OF KHATLON OBLAST IN THE REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN FINAL REPORT September 2012 Japan International Cooperation Agency NEWJEC Inc. E C C CR (1) 12-005 Final Report Contents, List of Figures, Abbreviations Data Collection Survey on the Installment of Small Hydropower Stations for the Communities of Khatlon Oblast in the Republic of Tajikistan FINAL REPORT Table of Contents Summary Chapter 1 Preface 1.1 Objectives and Scope of the Study .................................................................................. 1 - 1 1.2 Arrangement of Small Hydropower Potential Sites ......................................................... 1 - 2 1.3 Flowchart of the Study Implementation ........................................................................... 1 - 7 Chapter 2 Overview of Energy Situation in Tajikistan 2.1 Economic Activities and Electricity ................................................................................ 2 - 1 2.1.1 Social and Economic situation in Tajikistan ....................................................... 2 - 1 2.1.2 Energy and Electricity ......................................................................................... 2 - 2 2.1.3 Current Situation and Planning for Power Development .................................... 2 - 9 2.2 Natural Condition ............................................................................................................ -

Download Article (PDF)

ISSN 0375-1511 Rec. zool. Surv. India: 112(part-3) : 101-112,2012 OBSERVATIONS ON THE STATUS AND DIVERSITY OF BUTTERFLIES IN THE FRAGILE ECOSYSTEM OF LADAKH 0 & K) AVTAR KAUR SIDHU, KAILASH CHANDRA* AND JAFER PALOT** High Altitude Regional Centre, Zoological Survey of India, Solan, H.P. * Zoological Survey of India,M-Block, New Alipore, Kolkata 700 053. **Western Ghats Regional Centre, Zoological Survey of India, Calicut, Kerala INTRODUCTION between Zansker and Ladakh ranges and Nubra valley on the east side of Ladakh range crossing As one of the more inaccessible parts of the the Khardungla pass. The river Indus is the Himalayan Ranges, the cold deserts of India are backbone of Ladakh. resource poor regions. These could be considered as an important study area because of their As a distinct biome, this cold desert need extremely fragile ecosystem. The regions on the specially focused research and a concerted effort north flank of the Himalayas experience heavy in terms of natural resource management, snowfall and these remains virtually cut off from especially in the light of their vulnerable ecosystems the rest of the country for several months in the and highly deficient natural resource status. year. Summers are short. The proportion of oxygen Ecology and biodiversity of the Ladakh is under is less than in many other places at a comparable severe stress due to severe pressures. Ladakh and altitude because of lack of vegetation. There is little Kargil districts have been greatly disturbed since moisture to temper the effects of rarefied air. The 1962 because of extensive military activities. -

Uzbekistan: Tashkent Province Sewerage Improvement Project

Initial Environmental Examination May 2021 Uzbekistan: Tashkent Province Sewerage Improvement Project Prepared by the Joint Stock Companies “Uzsuvtaminot” for the Asian Development Bank. ..Þ,zýUçâÛ,ÜINÞâ'' .,UzSUVTAMINoT" »KSIYADORLIK J°¼IY»ÂI JoINT ýâÞáÚ áÞÜà°ItÓr 1¾¾¾35, O'zbekiston Respublikasi l0OO35, Republic of Uzbekistan Toshkent shahri, Niyozbek yo'li ko'chasi 1-çã Tashkent ciý, Niyozbek 5ruli stÛÕÕt 1 apt. telefon: +998 55 5Þ3 l2 55 telephone: +998 55 503 12 55 uzst14,exat.uz, infcl(rtluzsuv. çz æzst{o exat. uz, iÛ[Þ(Ð æzsçç, æz _ 2 Ñ 1,1AÙ 202l Nq 4l2L 1 4 2 Ò ÂÞ: ¼r. Jung ½Þ ºim Project Officer SÕßiÞr UrÌÐß Development Specialist ÁÕßtrÐl and West Asia DÕàÐÓtmÕßt UrÌÐß Development and Water Division °siÐß Development ²Ðßk Subject: Project 52045-001 Tashkent ÀrÞçißáÕ Sewerage lmprovement Project - Revised lnitial Environmental Examination Dear ¼r. Kim, We hÕrÕÌà endorse the final revised and updated version of the lnitial µßvirÞßmÕßtÐl Examination (lEE) àrÕàÐrÕd fÞr the Tashkent ÀrÞçißáÕ Sewerage lmprovement ÀrÞjÕát. The lEE has ÌÕÕß discussed and reviewed Ìã the Projecls Coordination Unit ußdÕr JSc "UZSUVTAMlNoT". We ÕßSçrÕ, that the lEE will ÌÕ posted Þß the website of the JSC "UZSUVTAMlNoT" to ÌÕ available to the project affected àÕÞà|Õ, the printed áÞàã will also ÌÕ delivered to Ñ hokimiyats for disclosure to the local people. FuÓthÕr, hereby we submit the lEE to ADB for disclosure Þß the ÔD² website. Sincerely, Rusta janov Deputy irman of the Board CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 1 May 2021) Currency unit – Uzbekistan Sum (SUM) -

65 Butterfly Diversity of Jayantikunj, Rewa (M.P.)

International Journal of Advanced Research and Development ISSN: 2455-4030, Impact Factor: RJIF 5.24 www.newresearchjournal.com/advanced Volume 1; Issue 4; April 2016; Page No. 65-69 Butterfly diversity of Jayantikunj, Rewa (M.P.) 1 Pinky Suryawanshi, 2 Arti Saxena 1 Research Scholar, Zoology Deptt., Govt. Science College, Rewa (M.P.), A.P.S. University, Rewa (M.P.). 2 Professor of Zoology Govt. Science College, Rewa (M.P.). Abstract The investigation was conducted at the Jayantikunj, Rewa (M.P.). It is situated at the western site of Govt. Science College Hostel, Rewa (M.P.). Butterfly watching and recording was done in such a way that there should be least one visit in each line transect during a week with the aid of binocular and digital cameras. Total 138 species of butterflies were recorded belonging to 117 genera and 11 families. Lycaenidae family is consisting of maximum number of genera and species. During unfavourable seasons, that in spring and summer, a low population found. Grass yellow (Eurema spp; family pieridae) had high population in all seasons in spring or summer depending on the site. Keywords: Butterfly; Lepidoptera; biodiversity; Jayantikunj 1. Introduction College Hostel, Rewa (M.P.). It is about 0.023 hectares. In There are 1.4 million species on earth; over 53% are insects Jayantikunj rare, vulnurable, medicinal and Threatned species while about 15,000-16,000 species of butterflies are known of plants were planted in the nursery for selling. Besides worldwide (Hossan, 1994) [1]. Butterflies have been regarded planted trees, a variety of annual wild plants and perennial as the symbol of beauty and grace (Rafi et al., 2000) [2]. -

Estimations Relative to Birds of Prey in Captivity in the United States of America

ESTIMATIONS RELATIVE TO BIRDS OF PREY IN CAPTIVITY IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA by Roger Thacker Department of Animal Laboratories The Ohio State University Columbus, Ohio 43210 Introduction. Counts relating to birds of prey in captivity have been accomplished in some European countries; how- ever, to the knowledge of this author no such information is available in the United States of America. The following paper consistsof data related to this subject collected during 1969-1970 from surveys carried out in many different direc- tions within this country. Methods. In an attempt to obtain as clear a picture as pos- sible, counts were divided into specific areas: Research, Zoo- logical, Falconry, and Pet Holders. It became obvious as the project advanced that in some casesthere was overlap from one area to another; an example of this being a falconer working with a bird both for falconry and research purposes. In some instances such as this, the author has used his own judgment in placing birds in specific categories; in other in- stances received information has been used for this purpose. It has also become clear during this project that a count of "pets" is very difficult to obtain. Lack of interest, non-coop- eration, or no available information from animal sales firms makes the task very difficult, as unfortunately, to obtain a clear dispersal picture it is from such sourcesthat informa- tion must be gleaned. However, data related to the importa- tion of birds' of prey as recorded by the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife is included, and it is felt some observa- tions can be made from these figures. -

Journal of Threatened Taxa

PLATINUM The Journal of Threatened Taxa (JoTT) is dedicated to building evidence for conservaton globally by publishing peer-reviewed artcles OPEN ACCESS online every month at a reasonably rapid rate at www.threatenedtaxa.org. All artcles published in JoTT are registered under Creatve Commons Atributon 4.0 Internatonal License unless otherwise mentoned. JoTT allows unrestricted use, reproducton, and distributon of artcles in any medium by providing adequate credit to the author(s) and the source of publicaton. Journal of Threatened Taxa Building evidence for conservaton globally www.threatenedtaxa.org ISSN 0974-7907 (Online) | ISSN 0974-7893 (Print) Communication A second report on butterflies (Lepidoptera) from Ladakh Union Territory and Lahaul, Himachal Pradesh, India Sanjay Sondhi, Balakrishnan Valappil & Vidya Venkatesh 26 May 2020 | Vol. 12 | No. 8 | Pages: 15817–15827 DOI: 10.11609/jot.5606.12.8.15817-15827 For Focus, Scope, Aims, Policies, and Guidelines visit htps://threatenedtaxa.org/index.php/JoTT/about/editorialPolicies#custom-0 For Artcle Submission Guidelines, visit htps://threatenedtaxa.org/index.php/JoTT/about/submissions#onlineSubmissions For Policies against Scientfc Misconduct, visit htps://threatenedtaxa.org/index.php/JoTT/about/editorialPolicies#custom-2 For reprints, contact <[email protected]> The opinions expressed by the authors do not refect the views of the Journal of Threatened Taxa, Wildlife Informaton Liaison Development Society, Zoo Outreach Organizaton, or any of the partners. The journal, the publisher, -

Biodiversity Profile of Afghanistan

NEPA Biodiversity Profile of Afghanistan An Output of the National Capacity Needs Self-Assessment for Global Environment Management (NCSA) for Afghanistan June 2008 United Nations Environment Programme Post-Conflict and Disaster Management Branch First published in Kabul in 2008 by the United Nations Environment Programme. Copyright © 2008, United Nations Environment Programme. This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. UNEP would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the United Nations Environment Programme. United Nations Environment Programme Darulaman Kabul, Afghanistan Tel: +93 (0)799 382 571 E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.unep.org DISCLAIMER The contents of this volume do not necessarily reflect the views of UNEP, or contributory organizations. The designations employed and the presentations do not imply the expressions of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP or contributory organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or its authority, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Unless otherwise credited, all the photos in this publication have been taken by the UNEP staff. Design and Layout: Rachel Dolores -

Diversity and Distribution of Butterflies in Pakistan

Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies 2016; 4(5): 579-585 E-ISSN: 2320-7078 P-ISSN: 2349-6800 Diversity and distribution of butterflies in JEZS 2016; 4(5): 579-585 © 2016 JEZS Pakistan: A review Received: 22-07-2016 Accepted: 23-08-2016 Salma Batool Salma Batool and Dr. Mubashar Hussain Department of Zoology, University of Gujrat Hafiz Abstract Hayat Campus, Gujrat, Pakistan The main purpose of this review paper is to check the diversity and distribution of butterflies in different Dr. Mubashar Hussain areas of Pakistan. The main study areas included Bhawalpur, Multan, Tolipir national park, Azad and Assistant Professor, University Jamu Kashmir, Union Council Koaz Bahram Dheri Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Faisalabad, Districts (Kotli, of Gujrat Hafiz Hayat Campus, Mirpur and Bhimber) of Azad Kashmir, Sindh, Jamshoro district(Sindh), District Muzaffarabad, Azad Gujrat, Pakistan Kashmir, Karachi, Lahore, West Pakistan, Rawalpindi and Islamabad, Northwest Himalaya (Galgit and Azad Kashmir), Islamabad and Murree, Poonch division of Azad Kashmir, Kabal, Swat, Tehsil Tangi (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa), Hazara University(garden campus, Mansehra), Kohat (Khyber Pakhtunkhwa), Murree, Chitral. The highest diversity of butterflies present in Bhawalpur. The total number of 4397 specimens, which were recognized into 19 families and 70 species from Bhawalpur. The areas rich in plant diversity show high butterfly diversity. Keywords: Diversity, butterfly, Pakistan, distribution Introduction Butterflies belong to Order Lepidoptera which is the second-largest order of insects. Lepidoptera is one of the most widespread and widely recognizable insect order in the world [1]. More than 28,000 species of butterflies present worldwide and about 80% found in tropical regions. More than 5,000 species of insects including 400 species of butterflies and moths [19] have been reported from Pakistan. -

Strigiformes) and Lesser Nighthawks (Chodeiles Acutipennis

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE The Evolution of Quiet Flight in Owls (Strigiformes) and Lesser Nighthawks (Chodeiles acutipennis) A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Evolution, Ecology, and Organismal Biology by Krista Le Piane December 2020 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Christopher J. Clark, Chairperson Dr. Erin Wilson Rankin Dr. Khaleel A. Razak Copyright by Krista Le Piane 2020 The Dissertation of Krista Le Piane is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I thank my Oral Exam Committee: Dr. Khaleel A. Razak (chairperson), Dr. Erin Wilson Rankin, Dr. Mark Springer, Dr. Jesse Barber, and Dr. Scott Curie. Thank you to my Dissertation Committee: Dr. Christopher J. Clark (chairperson), Dr. Erin Wilson Rankin, and Dr. Khaleel A. Razak for their encouragement and help with this dissertation. Thank you to my lab mates, past and present: Dr. Sean Wilcox, Dr. Katie Johnson, Ayala Berger, David Rankin, Dr. Nadje Najar, Elisa Henderson, Dr. Brian Meyers Dr. Jenny Hazelhurst, Emily Mistick, Lori Liu, and Lilly Hollingsworth for their friendship and support. I thank the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County (LACM), the California Academy of Sciences (CAS), Museum of Vertebrate Zoology (MVZ) at UC Berkeley, the American Museum of Natural History (ANMH), and the Natural History Museum (NHM) in Tring for access to specimens used in Chapter 1. I would especially like to thank Kimball Garrett and Allison Shultz for help at LACM. I also thank Ben Williams, Richard Jackson, and Reddit user NorthernJoey for permission to use their photos in Chapter 1. Jessica Tingle contributed R code and advice to Chapter 1 and I would like to thank her for her help.