The Universe

Total Page:16

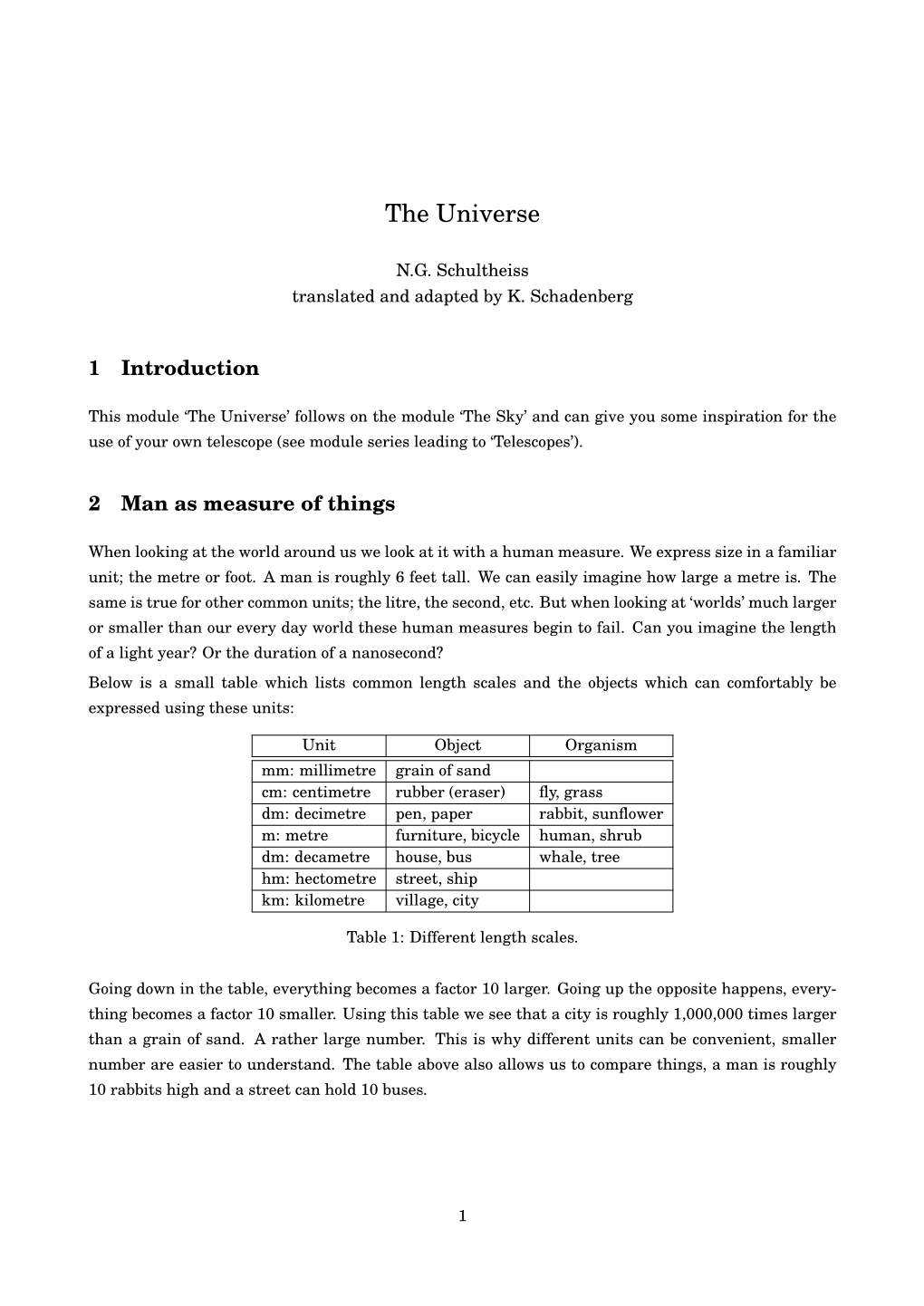

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Measurement Units Style Guide a Writer’S Guide to the Correct Usage of Metric Measurement Units

Measurement units style guide A writer’s guide to the correct usage of metric measurement units This guidance is based on British and internationally agreed standards and represents best practice. It gives advice on how to use and write metric units, mistakes to avoid, what to do about conversions, and where to find further information. A brief explanation of how the metric system works is also given. Some common units Basic rules name symbol Capitals and lower case millimetre mm Names of metric units, whether alone or combined with a prefix, always start with a lower case letter (except at centimetre cm length the beginning of a sentence) - e.g. metre, milligram, watt. metre m kilometre km The symbols for metric units are also written in lower case - except those that are named after persons - e.g. milligram mg m for metre, but W for watt (the unit of power, named after the Scottish engineer, James Watt). Note that this mass gram g rule applies even when the prefix symbol is in lower case, (weight) kilogram kg as in kW for kilowatt. The symbol for litre (L) is an exception. tonne t Symbols for prefixes meaning a million or more are square metre 2 m written in capitals, and those meaning a thousand or less area hectare ha are written in lower case - thus, mL for millilitre, kW for kilowatt, MJ for megajoule (the unit of energy). square kilometre km 2 Plurals millilitre mL or ml Symbols do not change and are never pluralised : 3 cubic centimetre cm 25 kg (but 25 kilograms) volume litre L or l cubic metre m3 Punctuation and spacing watt W Do not put a full stop (period) after a unit symbol (except power kilowatt kW at the end of a sentence). -

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI)

Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) m kg s cd SI mol K A NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Ambler Thompson and Barry N. Taylor NIST Special Publication 811 2008 Edition Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Ambler Thompson Technology Services and Barry N. Taylor Physics Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology Gaithersburg, MD 20899 (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, 1995 Edition, April 1995) March 2008 U.S. Department of Commerce Carlos M. Gutierrez, Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology James M. Turner, Acting Director National Institute of Standards and Technology Special Publication 811, 2008 Edition (Supersedes NIST Special Publication 811, April 1995 Edition) Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Spec. Publ. 811, 2008 Ed., 85 pages (March 2008; 2nd printing November 2008) CODEN: NSPUE3 Note on 2nd printing: This 2nd printing dated November 2008 of NIST SP811 corrects a number of minor typographical errors present in the 1st printing dated March 2008. Guide for the Use of the International System of Units (SI) Preface The International System of Units, universally abbreviated SI (from the French Le Système International d’Unités), is the modern metric system of measurement. Long the dominant measurement system used in science, the SI is becoming the dominant measurement system used in international commerce. The Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of August 1988 [Public Law (PL) 100-418] changed the name of the National Bureau of Standards (NBS) to the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and gave to NIST the added task of helping U.S. -

Maths Objectives – Measurement

Maths Objectives – Measurement Key Stage Objective Child Speak Target KS 1 Y1 Compare, describe and solve practical problems for lengths and I use words such as long/short, longer/shorter, tall/short, double/half to heights [for example, long/short, longer/shorter, tall/short, describe my maths work when I am measuring. double/half]. KS 1 Y1 Compare, describe and solve practical problems for mass/weight When weighing, I use the words heavy/light, heavier than, lighter than [for example, heavy/light, heavier than, lighter than]. to explain my work. KS 1 Y1 Compare, describe and solve practical problems for capacity and When working with capacity, I use the words full/empty, more than, volume [for example, full/empty, more than, less than, half, half full, less than, half, half full and quarter to explain my work. quarter]. KS 1 Y1 Compare, describe and solve practical problems for time [for I can answer questions about time, such as Who is quicker? or What example, quicker, slower, earlier, later]. is earlier? KS 1 Y1 Measure and begin to record lengths and heights. I can measure the length or height of something and write down what measure. KS 1 Y1 Measure and begin to record mass/weight. I can measure how heavy an object is and write down what I find. KS 1 Y1 Measure and begin to record capacity and volume. I can measure the capacity of jugs of water and write down what I measure. KS 1 Y1 Measure and begin to record time (hours, minutes, seconds). I can measure how long something takes to happen - such as how long it takes me to run around the playground. -

Measurement-Resource-Book-1.Pdf

First Steps in Mathematics Measurement Understand Units and Resource Book 1 Direct Measure Improving the mathematics outcomes of students FSIM010 | First Steps in Mathematics: Measurement Book 1 © Western Australian Minister for Education 2013. Published by Pearson Canada Inc. First Steps in Mathematics: Measurement Resource Book 1 Understand Units and Direct Measure © Western Australian Minister for Education 2013 Published in Canada by Pearson Canada Inc. 26 Prince Andrew Place Don Mills, ON M3C 2T8 Text by Sue Willis with Wendy Devlin, Lorraine Jacob, Beth Powell, Dianne Tomazos, and Kaye Treacy for STEPS Professional Development on behalf of the Department of Education and Training, Western Australia. Photos: Ray Boudreau Illustrations: Neil Curtis, Vesna Krstanovich and David Cheung ISBN-13: 978-0-13-188205-8 ISBN-10: 0-13-188205-8 Publisher: Debbie Davidson Director, Pearson Professional Learning: Terry (Theresa) Nikkel Research and Communications Manager: Chris Allen Canadian Edition Consultants: Craig Featherstone, David McKillop, Barry Onslow Development House: Pronk&Associates Project Coordinator: Joanne Close Art Direction: Jennifer Stimson and Zena Denchik Design: Jennifer Stimson and David Cheung Page Layout: Computer Composition of Canada Inc. FSIM010 | First Steps in Mathematics: Measurement Book 1 © Western Australian Minister for Education 2013. Published by Pearson Canada Inc. Diagnostic Map: Measurement Matching and Emergent Phase Comparing Phase Quantifying Phase Most students will enter the Matching and Most students -

Standard Caption Abberaviation

TECHNICAL SHEET Page 1 of 2 STANDARD CAPTION ABBREVIATIONS Ref: T120 – Rev 10 – March 02 The abbreviated captions listed are used on all instruments except those made to ANSI C39. 1-19. Captions for special scales to customers’ requirements must comply with BS EN 60051, unless otherwise specified at time of ordering. * DENOTES captions applied at no extra cost. Other captions on request. ELECTRICAL UNITS UNIT SYMBOL UNIT SYMBOL Direct Current dc Watt W * Alternating current ac Milliwatts mW * Amps A * Kilowatts kW * Microamps µA * Megawatts MW * Milliamps mA * Vars VAr * Kiloamps kA * Kilovars kVAr * Millivolts mV * Voltamperes VA * Kilovolts kV * Kilovoltamperes kVA * Cycles Hz * Megavoltamperes MVA * Power factor cos∅ * Ohms Ω * Synchroscope SYNCHROSCOPE * Siemens S Micromhos µmho MECHANICAL UNITS Inches in Micrometre (micron) µm Square inches in2 Millimetre mm Cubic inches in3 Square millimetres mm2 Inches per second in/s * Cubic millimetres mm3 Inches per minute in/min * Millimetres per second mm/s * Inches per hour in/h * Millimetres per minute mm/min * Inches of mercury in hg Millimetres per hour mm/h * Feet ft Millimetres of mercury mm Hg Square feet ft2 Centimetre cm Cubic feet ft3 Square centimetres cm2 Feet per second ft/s * Cubic centimetres cm3 Feet per minute ft/min * Cubic centimetres per min cm3/min Feet per hour ft/h * Centimetres per second cm/s * Foot pound ft lb Centimetres per minute cm/min * Foot pound force ft lbf Centimetres per hour cm/h * Hours h Decimetre dm Yards yd Square decimetre dm2 Square yards yd2 Cubic -

The Square Kilometre Array (SKA) Will Be an I

INVITED PAPER TheSquareKilometreArray This telescope, to be the largest in the world, will probe the evolution of black holes as well as the basic properties, birth and death of the Universe. By Peter E. Dewdney, Peter J. Hall, Richard T. Schilizzi, and T. Joseph L. W. Lazio ABSTRACT | The Square Kilometre Array (SKA) will be an I. INTRODUCTION ultrasensitive radio telescope, built to further the understand- Advances in astronomy over the past decades have brought ing of the most important phenomena in the Universe, the international community to the verge of charting a including some pertaining to the birth and eventual death of complete history of the Universe. In order to achieve this the Universe itself. Over the next few years, the SKA will make goal, the world community is pooling resources and ex- the transition from an early formative to a well-defined design. pertise to design and construct powerful observatories that This paper outlines how the scientific challenges are translated will probe the entire electromagnetic spectrum, from radio to into technical challenges, how the application of recent gamma-rays, and even beyond the electromagnetic spectrum, technology offers the potential of affordably meeting these studying gravitational waves, cosmic rays, and neutrinos. challenges, and how the choices of technology will ultimately The Square Kilometre Array (SKA) will be one of these be made. The SKA will be an array of coherently connected telescopes, a radio telescope with an aperture of up to a antennas spread over an area about 3000 km in extent, with an million square meters. The SKA was formulated from the 2 aggregate antenna collecting area of up to 106 m at centimeter very beginning as an international, astronomer-led (Bgrass and meter wavelengths. -

Using Mathematical Operations to Convert Metric Linear Units

Converting Metric Linear Units Using Mathematical Operations to Convert Metric Linear Units Converting Larger to Smaller Units To convert from larger to smaller metric linear units, multiply by 10 for each step downward on the metric staircase. Metric Staircase Use this ACRONYM to help you remember the kilo King order of the units: hecto Henry’s King Henry’s deca Daughter Daughter base unit Betty Betty deci Detested Detested centi Counting Counting milli Money Money Examples A) How many cm in 1 m? m to cm is 2 steps Metric Staircase 1 m = 10 × 10 = 100 cm There are 100 cm in 1 m. m dm B) How many mm in 1 m? cm m to mm is 3 steps mm 1 m = 10 × 10 × 10 = 1000 mm There are 1000 mm in 1 m. Remember that 10 × 10 × 10 = 1000 10 × 10 = 100 C) How many mm in 4.2 m? 4.2 × 10 × 10 × 10 = 4200 mm OR 4.2 × 1000 = 4200 mm There are 4200 mm in 4.2 m. Knowledge and Employability Studio Shape and Space: Measurement: Mathematics Linear Measurement: ©Alberta Education, Alberta, Canada (www.LearnAlberta.ca) Converting Metric Linear Units 1/12 D) For every kilometre you travel in a car or school bus, you are travelling 1000 metres. How many metres in 69.7 kilometres? km to m is 3 steps Metric Staircase 10 × 10 × 10 = 1000 m There are 1000 m in 1 km. km 69.7 × 10 × 10 × 10 = 69 700 m hm OR dam 69.7 × 1000 = 69 700 m m There are 69 700 m in 69.7 km. -

Introducyon to the Metric System Bemeasurement, Provips0.Nformal, 'Hands-On Experiences For.The Stud4tts

'DOCUMENT RESUME ED 13A 755 084 CE 009 744 AUTHOR Cáoper, Gloria S., Ed.; Mag4,sos Joel B., Ed. TITLE q Met,rits for.Theatrical COstum g: ° INSTITUTION Ohio State Univ., Columbus. enter for Vocational Education. SPONS AGENCY Ohio State Univ., Columbus. Center for.Vocational Education. PUB DATE 76 4. CONTRACT - OEC-0-74-9335 NOTE 59p.1 For a. related docuMent see CE 009 736-790 EDRS PRICE 10-$0.8.3 C-$3.50 Plus Pdstage: DESCRIPTORS *Curriculu; Fine Arts; Instructional Materials; Learning. ctivities;xMeasurement.Instrnments; *Metric, System; S condary Education; Teaching Technigue8; *Theater AttS; Units of Sttidy (Subject Fields) ; , *Vocational Eiducation- IDENTIFIERS Costumes (Theatrical) AESTRACT . Desigliedto meet tbe job-related m4triceasgrement needs of theatrical costuming students,'thiS instructio11 alpickage is one of live-for the arts and-huminities occupations cluster, part of aset b*: 55 packages for:metric instrection in diftepent occupations.. .The package is in'tended for students who already knovthe occupaiiOnal terminology, measurement terms, and tools currently in use. Each of the five units in this instructional package.contains performance' objectiveS, learning:Activities, and'supporting information in-the form of text,.exertises,- ard tabled. In. add±tion, Suggested teaching technigueS are included. At the'back of the package*are objective-base'd:e"luation items, a-page of answers to' the exercises,and tests, a list of metric materials ,needed for the ,activities4 references,- and a/list of supPliers.t The_material is Y- designed. to accVmodate awariety of.individual teacting,:and learning k. styles, e.g., in,dependent:study, small group, or whole-class Setivity. -

CAR-ANS Part 5 Governing Units of Measurement to Be Used in Air and Ground Operations

CIVIL AVIATION REGULATIONS AIR NAVIGATION SERVICES Part 5 Governing UNITS OF MEASUREMENT TO BE USED IN AIR AND GROUND OPERATIONS CIVIL AVIATION AUTHORITY OF THE PHILIPPINES Old MIA Road, Pasay City1301 Metro Manila UNCOTROLLED COPY INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK UNCOTROLLED COPY CAR-ANS PART 5 Republic of the Philippines CIVIL AVIATION REGULATIONS AIR NAVIGATION SERVICES (CAR-ANS) Part 5 UNITS OF MEASUREMENTS TO BE USED IN AIR AND GROUND OPERATIONS 22 APRIL 2016 EFFECTIVITY Part 5 of the Civil Aviation Regulations-Air Navigation Services are issued under the authority of Republic Act 9497 and shall take effect upon approval of the Board of Directors of the CAAP. APPROVED BY: LT GEN WILLIAM K HOTCHKISS III AFP (RET) DATE Director General Civil Aviation Authority of the Philippines Issue 2 15-i 16 May 2016 UNCOTROLLED COPY CAR-ANS PART 5 FOREWORD This Civil Aviation Regulations-Air Navigation Services (CAR-ANS) Part 5 was formulated and issued by the Civil Aviation Authority of the Philippines (CAAP), prescribing the standards and recommended practices for units of measurements to be used in air and ground operations within the territory of the Republic of the Philippines. This Civil Aviation Regulations-Air Navigation Services (CAR-ANS) Part 5 was developed based on the Standards and Recommended Practices prescribed by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) as contained in Annex 5 which was first adopted by the council on 16 April 1948 pursuant to the provisions of Article 37 of the Convention of International Civil Aviation (Chicago 1944), and consequently became applicable on 1 January 1949. The provisions contained herein are issued by authority of the Director General of the Civil Aviation Authority of the Philippines and will be complied with by all concerned. -

The Astronomical Units

The astronomical units N. Capitaine and B. Guinot November 5, 2018 SYRTE, Observatoire de Paris, CNRS, UPMC 61, avenue de l’Observatoire, 75014 Paris, France e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract The IAU-1976 System of astronomical constants includes three astronomical units (i.e. for time, mass and length). This paper reports on the status of the astronomical unit of length (ua) and mass (MSun) within the context of the recent IAU Resolutions on reference systems and the use of modern observations in the solar system. We especially look at a possible re-definition of the ua as an astronomical unit of length defined trough a fixed relation to the SI metre by a defining number. Keywords: reference systems, astronomical constants, numerical standards 1. INTRODUCTION The IAU-1976 System of astronomical constants includes three astronomical units, namely the astronomical unit of time, the day, D, which is related to the SI by a defining number (D=86400 s), the astronomical unit of mass, i.e. the mass of the Sun, MSun, and the astronomical unit of length, ua. Questions related to the definition, numerical value and role of the astronomical units have been discussed in a number of papers, e.g. (Capitaine & Guinot 1995), (Guinot 1995), (Huang et al. 1995), (Standish 1995, 2004) and (Klioner 2007). The aim of this paper is to report on recent views on these topics. The role of the astronomical unit of time, which (as is the Julian century of 36 525 days) is to provide a unit of time of convenient size for astronomy, does not need further discussion. -

Orders of Magnitude (Length) - Wikipedia

03/08/2018 Orders of magnitude (length) - Wikipedia Orders of magnitude (length) The following are examples of orders of magnitude for different lengths. Contents Overview Detailed list Subatomic Atomic to cellular Cellular to human scale Human to astronomical scale Astronomical less than 10 yoctometres 10 yoctometres 100 yoctometres 1 zeptometre 10 zeptometres 100 zeptometres 1 attometre 10 attometres 100 attometres 1 femtometre 10 femtometres 100 femtometres 1 picometre 10 picometres 100 picometres 1 nanometre 10 nanometres 100 nanometres 1 micrometre 10 micrometres 100 micrometres 1 millimetre 1 centimetre 1 decimetre Conversions Wavelengths Human-defined scales and structures Nature Astronomical 1 metre Conversions https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orders_of_magnitude_(length) 1/44 03/08/2018 Orders of magnitude (length) - Wikipedia Human-defined scales and structures Sports Nature Astronomical 1 decametre Conversions Human-defined scales and structures Sports Nature Astronomical 1 hectometre Conversions Human-defined scales and structures Sports Nature Astronomical 1 kilometre Conversions Human-defined scales and structures Geographical Astronomical 10 kilometres Conversions Sports Human-defined scales and structures Geographical Astronomical 100 kilometres Conversions Human-defined scales and structures Geographical Astronomical 1 megametre Conversions Human-defined scales and structures Sports Geographical Astronomical 10 megametres Conversions Human-defined scales and structures Geographical Astronomical 100 megametres 1 gigametre -

Metrication Leaders Guide 2009

Metrication Leaders Guide This resource book will help make your inevitable upgrade to the metric system easy, smooth, cheap, and fast. Pat Naughtin 2009 2 of 89 Make your upgrade to the metric system easy, smooth, cheap, and fast Decision making for metrication leaders !! " ! # $ Appendices % & % ! !! ' ! ( )% ' !* " " + , -&..)--/& , - ,$ # ! ,, 0 * + # ( http://metricationmatters.com [email protected] 3 of 89 Make your upgrade to the metric system easy, smooth, cheap, and fast. Deciding on a metrication program confirms that you are a metrication leader – not a follower. You have the courage to stand aside from the crowd, decide what you think is best for yourself and for others, and you are prepared to differ from other people in your class, your work group, your company, or your industry. As a metrication leader, you will soon discover three things: 1 Metrication is technically a simple process. 2 Metrication doesn't take long if you pursue a planned and timed program. 3 Metrication can provoke deeply felt anti-metrication emotions in people who have had no measurement experience with metric measures, or people who have difficulty with change. The first two encourage confidence – it's simple and it won't take long – but the third factor can give you an intense feeling of isolation when you first begin your metrication program. You feel you are learning a new language (you are – a new measuring language), while people around you not only refuse to learn this language, but will do what they can to prevent you from growing and from making progressive developments in your life. The purpose of this book is to give you some supporting arguments to use in your metrication process.