Ardea 94(3): 639–650

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oversight and Reauthorization Hearing on the Rehabilitation Act of 1983

DOCUMEIIT RESUME ED 249 748 EC 170 860 TITLE Ove- ght and Reauthorization Hearing on the Rehabilitation Act of 1983. Bearings before the Subcot 'Nitta. on Select Education of the Committee on Education and Labor. Rouse of Representatives, Ninety -- Eighth Congress, First Session Narch 21 and 23, 1983). INSTITUTION Congress of the U.S., Washington, D.C.Rouse Commettee on Education and Labor. PUB DATE 84; NOTE ' FUR TYPE 4114*I 1/Legislative/Regulatory Materials (090) EDRS PRICE NFO1 /FC18 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Compliance (Legal); Disabilities; *Federal Legislation; Federal Programs; Bearings; Rehabilitation; *Vocational Rehabilitation 'IDENTIFIERS *Rehabilitation Act 1973 ABSTRACT Excerpts are presented from the March 1983 hearings on oversight and reauthorization of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. Prepared statements are included from federal officials; representatives of professional rehabilitation and education associations and state and local agencies; etudents; and other interested persons. In addition to the statements, letters and supplemental materials on the topic are also, provided from associations, agencies, university faculty, and federal officials. The statements touch on amendisents to the act, provisions for independent living, rehabilitation research, and rehabilitation training. (CL) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRA are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** -

Bush Sort Victorieux Des Élections

www.lemonde.fr 58e ANNÉE – N 17973 – 1,20 ¤ – FRANCE MÉTROPOLITAINE --- JEUDI 7 NOVEMBRE 2002 FONDATEUR : HUBERT BEUVE-MÉRY – DIRECTEUR : JEAN-MARIE COLOMBANI Le nouveau visage Bush sort victorieux des élections d’« aden » A mi-mandat présidentiel, le Parti républicain est majoritaire au Congrès après le scrutin du 5 novembre LES RÉPUBLICAINS ont rem- f LE GUIDE des sorties culturelles porté une victoire remarquable Le parti revient cette semaine dans une for- aux élections du mardi 5 novem- du président mule rénovée. En cinq rubriques – bre, donnant au président George Musiques, Cinéma, Scènes, Arts et W. Bush la majorité dans les deux a la majorité dans En famille –, aden, distribué en Ile- Chambres du Congrès. Mal élu en de-France, propose une sélection 2000, M. Bush voit son assise politi- les deux Chambres de sorties, de spectacles, les dates que renforcée par un succès électo- du Congrès des concerts à réserver dès mainte- ral qui lui donne une marge de nant, un choix de disques et de manœuvre plus grande encore f DVD. dans la stratégie qu’il entend sui- La Maison Blanche Autre innovation : notre supplé- vre face à l’Irak. Sur ce front-là éga- confortée ment, disponible en version Web, lement, il devrait enregistrer cette et sa newsletter sont accessibles semaine un succès avec le vote par gratuitement à l’adresse le Conseil de sécurité de l’ONU fIrak : l’ONU prête http://aden.lemonde.fr. d’une résolution très contraignan- Notre supplément te pour le régime de Bagdad. à voter la résolution Ce scrutin dit de mi-mandat pré- américaine sidentiel voit en général le parti du ROBERT HUE S’EN VA président perdre du terrain au Con- grès. -

Parasites of Seabirds: a Survey of Effects and Ecological Implications Junaid S

Parasites of seabirds: A survey of effects and ecological implications Junaid S. Khan, Jennifer Provencher, Mark Forbes, Mark L Mallory, Camille Lebarbenchon, Karen Mccoy To cite this version: Junaid S. Khan, Jennifer Provencher, Mark Forbes, Mark L Mallory, Camille Lebarbenchon, et al.. Parasites of seabirds: A survey of effects and ecological implications. Advances in Marine Biology, Elsevier, 2019, 82, 10.1016/bs.amb.2019.02.001. hal-02361413 HAL Id: hal-02361413 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02361413 Submitted on 30 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Parasites of seabirds: a survey of effects and ecological implications Junaid S. Khan1, Jennifer F. Provencher1, Mark R. Forbes2, Mark L. Mallory3, Camille Lebarbenchon4, Karen D. McCoy5 1 Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment and Climate Change Canada, 351 Boul Saint Joseph, Gatineau, QC, Canada, J8Y 3Z5; [email protected]; [email protected] 2 Department of Biology, Carleton University, 1125 Colonel By Dr, Ottawa, ON, Canada, K1V 5BS; [email protected] 3 Department of Biology, Acadia University, 33 Westwood Ave, Wolfville NS, B4P 2R6; [email protected] 4 Université de La Réunion, UMR Processus Infectieux en Milieu Insulaire Tropical, INSERM 1187, CNRS 9192, IRD 249. -

Oil and Gas in America's Arctic Ocean

Oil and Gas in America’s Arctic Ocean: Past Problems Counsel Precaution Michael LeVine, Peter Van Tuyn, Layla Hughes* “Although it can be a forbidding moonscape, the Arctic is also var- ied, majestic, serene, memorably beautiful and occasionally gentle. The far north is not only a prowling bear, a battering storm and vi- cious cold, but also a fat bumblebee buzzing among delicately yel- low arctic poppies.”1 “I believe there will not be an oil spill.”2 I. INTRODUCTION For most of history, the U.S. Arctic Ocean was protected from large-scale industrial activities by sea ice, remoteness, and plentiful re- sources in other, more accessible regions. That reality is rapidly changing as receding sea ice and the growing world demand for resources have led to increased corporate interest in the Arctic Ocean. This industrial pres- sure occurs against the backdrop of a swiftly changing climate, an ab- sence of holistic planning for the future of the region, missing scientific information, and a lack of proven technologies. The potential for industrial development in the America’s Arctic Ocean has generated substantial controversy. At the center of this con- troversy are a series of decisions made by the federal government to al- low offshore oil and gas activities in the Chukchi and Beaufort seas. * Michael LeVine is Pacific Senior Counsel for Oceana, an international nonprofit organization dedicated to maintaining and restoring ocean ecosystems. He is based in Juneau, AK. Peter Van Tuyn is an environmental attorney with the law firm Bessenyey & Van Tuyn, L.L.C., located in Anchorage, AK. -

Snake River Sporting Club Development Permit 02-0024

Snake River Fund letter - Snake River Sporting Club Development Permit 02-0024 violations ait.d Baecker <[email protected]> Tue 11/13/2018 1:12 PM io’ Haruifton Smith <[email protected]>; Susan Johnson <[email protected]>; Chandler Windorn <cwi ndorn (Otetoncountywy.gov>; Cc.Board Of County Commissioners <[email protected]>; [email protected] <[email protected]>; Mary Moore <[email protected]>; David Cernicek <[email protected]>; Michael T Happold <[email protected]>; Luther Propst <[email protected]>; [email protected] <[email protected]>; I urn ,in,nnt.s 213 KB) 20181113SRF_TCPD_SRSC,,yiohitions letter.pdf; Dear Susan, Humilton & Chandler (as well as CC’d parties): Pime,e find the Snake River Fund’s ,ittaclred kttei imploring Teton County and other agency partners to follow the law, rules, and procedtire set forth in tue tnm rim’, of eton County’s Development Permit 02—0024 issued Snake River Sporting Club and its agents. Viukriams of this cievimlopriment permit and its conditions are evident. The Wilc] and Scernic Snake River needs to be protect from these very actions. The Snake River is a local and national asset. Locally the Snake River is both arid ecological and economic artery to our community. Nationally, the Snake River is an icon of free flowing wildness. Uphold tIre rules, regulations, and laws of our land, deny all after—the-fact perrrrt applications before you with regaids to bank stabilization and channel nltwahons on the Snake River, its side channels and banks. Si ice rely, Jared Baeckei Jared Baecker Executive Dir ector Snake River Func) iC k’ ‘NY 83002 0: (307) 734-6773 C: 307) 200-1653 To stop receiving messages from Board Of County Commissioners group, stop following it, Snake River Fund PC Box 7033 Jackson, WY 83002 307-734-6773 snake rivet f tin d.c ig in to @5 flake river t u n d.c r g Susan Johnson November 13, 2018 Hamilton Smith Chandler Windom Teton County Planning Department 200 S. -

Biological Opinion for the National Petroleum Reserve – Alaska Integrated Activity Plan 2013

F8 Biological Opinion for the National Petroleum Reserve – Alaska Integrated Activity Plan 2013 Prepared by: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Fairbanks Fish and Wildlife Field Office 101 12th Ave, Room 110 Fairbanks, Alaska 99701 February 5, 2013 1 Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 9 The Action Area ............................................................................................................................ 12 The Proposed Action..................................................................................................................... 12 Actions Common to Multiple Oil and Gas Activities ........................................................... 14 Staging Areas .................................................................................................................... 14 Aircraft Flights .................................................................................................................. 14 Construction of Roads (gravel and winter ice roads) ........................................................ 14 Summer support work ....................................................................................................... 17 Management of wastes ...................................................................................................... 17 Development and Production Scenario ................................................................................ -

Lcfs15isor.Pdf

California Environmental Protection Agency Air Resources Board STAFF REPORT: INITIAL STATEMENT OF REASONS FOR PROPOSED RULEMAKING PROPOSED RE-ADOPTION OF THE LOW CARBON FUEL STANDARD Industrial Strategies Division Transportation Fuels Branch Oil & Gas and GHG Mitigation Branch December 2014 This Page Left Intentionally Blank State of California AIR RESOURCES BOARD STAFF REPORT: INITIAL STATEMENT OF REASONS FOR RULEMAKING PROPOSED RE-ADOPTION OF THE LOW CARBON FUEL STANDARD REGULATION Date of Release: January 2, 2015 Scheduled for Consideration: February 19, 2015 This report has been reviewed by the staff of the California Air Resources Board and approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and policies of the Air Resources Board, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. State of California AIR RESOURCES BOARD This Page Left Intentionally Blank Acknowledgments This report was prepared with the assistance and support from many individuals within the Air Resources Board. In addition, staff would like to acknowledge the assistance and cooperation from many individuals from other divisions and offices of the Air Resources Board, whose contributions throughout the development process have been invaluable. Staff would like to acknowledge the cooperation from the numerous State, federal, and governmental agencies that have provided assistance throughout the rulemaking process. Staff would also like to acknowledge the invaluable -

The Hansen Shipping Photographic Collection

The Hansen Shipping Photographic Collection A Catalogue Compiled By Donald A. Taylor The Hansen Shipping Photographic Collection Name of Vessel Catalogue Type Engine Position Flag View of Dock Other Vessels Supplemetary Approx. date of Number of Mach. Vessel Information photo A960 (HMS) 3475/83A ? UK ¾ S Bow Cardiff 1972/4 A961 (HMS) 3661/10D ? UK Stern Cardiff Lock Tug (Stern) 1972/4 LOWGARTH A961 (HMS) 3662/10D ? UK P Bow Cardiff 1972/4 A961 (HMS) 3663/10D ? UK P Bow Cardiff 1972/4 A961 (HMS) 3664/10D ? UK ¾ P Bow Cardiff 1972/4 A961 (HMS) 3665/10D ? UK ¾ S Stn Cardiff 1972/4 * A ANDREEW 448/756 GC M AFT USSR P Bs Cardiff FP Timber deck 1936/7 cargo A J FALKLAND 2676/2707 GC ST MID SW P Bow Cardiff FP Timber deck 1948/9 cargo A L KENT 2820/2842 GC ST MID PA ¾ P Bow Penarth Head Watermans boat 3 IS 1949 AAGOT 386/694 GC ST MID F ¾ P Bow Penarth Head Watermans boat 3 IS Deck cargo pit 1936/7 props AAGOT 392/700 GC ST MID F S Bs 3 IS Deck cargo pit 1936/7 props AASE MAERSK 1851/1929 T M AFT D ¾ S Bow 3 IS 23/12/1947 ABELONE VENDILA 3392/25A GC M MID D S Bs Cardiff 3 IS Timber deck 1962/3 cargo * ABSALON 420/728 GC ST MID D P Bs 3 IS Timber deck 1936/7 cargo, Discharging * ABSIRTEA 414/722 GC ST MID I P Bs Penarth Head Watermans boat, Tug WDA 1936/7 ABU 3390/23A T M AFT NY S Bow Cardiff FP 1964/5 ABGARA 406/714 GC ST MID LA P Bs Cardiff 3 IS 1936/7 ACAVUS 2229/2287 T M AFT UK ¾ S Stn Cardiff 3 IS 1948 ACHEO 1518/1615 Cable Layer ST MID I ¾ S Bow FD 13/05/1947 ACROPOLIS 2946/2966 GC ST MID PA P Bs Cardiff LBD 1950 ACROPOLIS 2947/2966 GC ST MID PA P Bs Cardiff LBD 1950 ACTUALITY 2276/2331 C M AFT UK ¾ S Stn RQ 1948 ADAK 3467/77A Bulk Ore M AFT SW P Stn Cardiff FP 1972/4 HMS ADAMANT 3431/52A S UK ¾ S Bow Tug - WELSH ROSE HMS ADAMANT 3432/52A S UK ¾ S Bow HMS ADAMANT 3433/52A S UK ¾ S Bow Entering Cardiff HMS ADAMANT 3434/52A S UK ¾ S Bow Entering Cardiff Similar Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales 1 of 146 The Hansen Shipping Photographic Collection HMS ADAMANT 3435/52A S UK ¾ S Bow 4 Tugs HMS ADAMANT 3436/52A S UK S Quarter Cardiff ADAMTIOS J. -

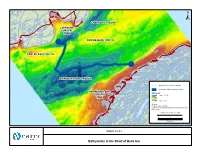

Bathymetry in the Strait of Belle Isle

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !!! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! L'Anse Amour ! -80 -60 ! Forteau -50 ! ± LABRADOR TROUGH LABRADOR COASTAL -100 ZONE -80 -80 -1 00 L'Anse-au-Clair ! CENTRE BANK NORTH -90 ! -50 CENTRE BANK SOUTH -40 -60 0 -100 Green Island Cove 5 -60 ! - -80 -90 ! Pines Cove ! -100 Shoal Cove ! Sandy Cove ! NEWFOUNDLAND TROUGH -10 -20 Savage Cove ! -9 0 -30 Bathymetry Lines (10 m interval) 00 -1 Submarine Cable Crossing Corridor - ! 1 0 0 0 NEWFOUNDLAND -1 0 Bathymetry * COASTAL High : 127.09 -2 Flower's Cove ZONE0 ! -70 Low : -0.16 Sources: * Fugro Jacques (2007) Location of troughs and banks from Woodworth-Lynas et al. (1992). -60 FIGURE ID: HVDC_ST_406a ! 0 3 6 0 Kilometres -5 -80 ! ! FIGURE 10.5.2-2 ! Bathymetry in the Strait of Belle Isle ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !!! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! -

IRON WORKS CO. CLOTHING HOUSE, L. KLINE & Co

WASHINGTON IRON WORKS CO. Foundry and Machine Shops, / - CORNER OF SECOND AND JACKSON STREETS. ENGINES AND MACHINERY Of all kinds built, estimated for and repaired. Castings of all kinds, in Iron and Brass, including House Work. Pattern Shop in connection with the Works. TO SAVE MONEY, Buy your Clothing and Gent's Furnishing Goods at the STAR CLOTHING HOUSE, 208 COMMERCIAL STREET, L. KLINE & Co., Leading Clothiers and Hatters. SEATTLE DIRECTORY. O. W. LYNCH. L. M. WOOD. LYNCH & WOOD, DEALERS IN FURNITURE Bedding, Wlatfrasses, Lounges and Parlor Sets OF THE LATEST STYLE. Window Shades, ' Window Cornices, Poles, Curtains and Lam brequins. Carpets sewed and laid with dispatch and in a workmanlike manner. Fine Upholsters' a Specialtj'. 917 Front Street, Seattle. <&» DRAYAGE.^ Every faciBify for delivering freight, moving ma chinery and Safes, and heavy materiaB. Goods handSed carefuBBy and satisfaction guaranteed. Coai deBivered to any part of the city. D. RflcDilftSIEL, Drayman, P. 0. Box 27. SEATTLE BiiJISS &M& BELL FOyHDRY. JOHN E. GOOD &CO., Steamboat? Railroad! and MM Castings, Also Babbit-Metals of all grades on hand and made to order at .short notice and of best material. First-class work guaranteed. Brass finishing in all its branches. Old Copper, Brass and Lead wanted. 421 Commercial street, [P. O. Box 769], Seattle. MEDICAL BATHS, Office on Mill street, below Post Office, SEATTLE, W. T. Invalids who may desire to investigate my new and improved method of treating the body for the different ailments are cordially invited to my institution. DP. H. I)DANE. VILLARD HOUSE, C. S. PLOUGH, Proprietor. No. -

Multi-Year Counts of Sea Ducks and Gulls in the Nearshore of the Pribilof Islands, Alaska

NORTHWESTERN NATURALIST 98:215–227 WINTER 2017 MULTI-YEAR COUNTS OF SEA DUCKS AND GULLS IN THE NEARSHORE OF THE PRIBILOF ISLANDS, ALASKA STEPHEN JINSLEY Wildlife Conservation Society, 169 Titanium Way, Whitehorse, YT Y1A 0E9 Canada, and Department of Biology, University of Victoria, 3800 Finnerty Rd, Victoria, BC V8P 5C2 Canada; [email protected] PAUL IMELOVIDOV,DUSTIN JJONES Aleut Community of St. Paul Island, Tribal Government, Ecosystem Conservation Office, 2050 Venia Minor Road, St. Paul Island, AK 99660 USA BRUCE WROBSON Community and Ecology Resources, LLC, 2442 NW Market Street #761, Seattle, WA 98107 USA PHILLIP AZAVADIL Aleut Community of St. Paul Island, Tribal Government, Ecosystem Conservation Office, 2050 Venia Minor Road, St. Paul Island, AK 99660 USA ROSANA PAREDES Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, 104 Nash Hall, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331 USA ABSTRACT—Monitoring avian populations over both the reproductive and non-reproductive seasons is required to better understand population changes. Obtaining baseline data in remote sites, however, is often difficult during the non-breeding season, especially in ice-driven ecosystems. We determined annual changes in numbers of over-wintering sea duck and large-bodied gull species and identified their main areas of concentration at one of the Pribilof Islands (St. Paul) in the Bering Sea. Formally trained local citizens undertook weekly counts using standardized methods over 3 non-breeding seasons (2008–2009; 2009–2010; 2010–2011) from late autumn to early spring. Sea ducks and large-bodied gulls were present nearshore in considerable numbers from November to January, and maximum counts usually occurred between February and March when sea-ice cover is at its maximum near the Pribilof Islands. -

Kootenai County Republican (Rathdrum, Idaho), 1902-02-21, [P ]

f the littlo city of Monterey, committed ly belonged to one of the many wood suicide Sunday night in a lodging chopping crew» in the vicinity. The house at Seattle. Less than an hour ffen tn « mu later Edith Curran, a beautiful 19-year- man's head was completely severed I« from the body. FROM DISPATCH£S °ld g,r1' vvho had been employed as a waitress in a hotel also NEWS HERE IS BRIEFLY TOLD. HEAD OF THE STEEL TRUST. t restaurant, OHEGON notbs. ended her life. Both took carbolic acid. IE. Review of Happenings in Both Despondency was the cause Of the 4500 cattle put in winter feed- in both < hoii-e selection ot inirrrutui item« ing quarters on Butter creek this win- filtern and Western Hemisphere« Cases. He tin« Hern Spending Two Months Guthered Thruuich the Rrrk — ter over half have been shipped out Haring the !*nat Week—National. Chairman Mercer of the house pub- Traveling Oxer the Continent and T*luHt Ex ery- and over three quarters sold. Hlaioricnl, Political and Penonai lie buildings committee has informed Srclion Shims General England—Waa Aeenmpanled by The Oregon Railroad & Navigation Representative Jones that in his opin-; Growth—Msiif Accidents Occur» ■ Wife and Slater—Trade Outlook U »U. gventa Teraely Expounded. company today chartered the steam- ; ion his committee would favorably re-1 Personals. ship Indrasamha, a new 10.00»» ton ves-; Eavorable. e BelW I port the bills recently passed by the! sei, to take the place of the steamship v® Rev. George Carter Needham, the senate making appropriations for pub-1 Knight Companion, which was wreck-; ioted evangelish, is dead.