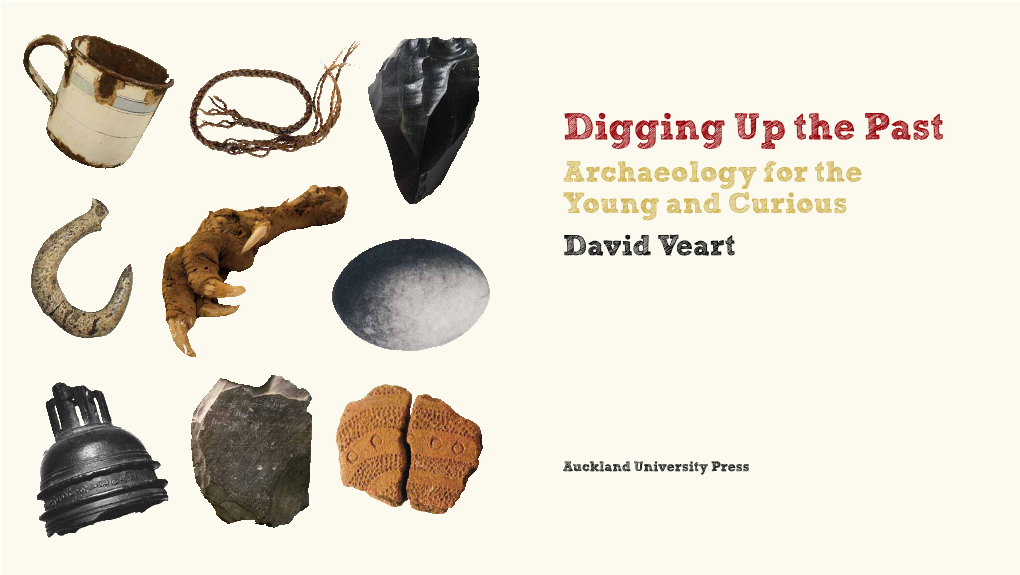

Digging up the Past Archaeology for the Young and Curious David Veart

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rhamnus Alaternus - Environmental Weed on Motutapu and Rangitoto Islands, Auckland

Tane 36: 57-66 (1997) RHAMNUS ALATERNUS - ENVIRONMENTAL WEED ON MOTUTAPU AND RANGITOTO ISLANDS, AUCKLAND Mairie L. Fromont CI- School of Environmental and Marine Sciences, Tamaki Campus, University of Auckland, Private Bag 92019, Auckland SUMMARY Rhamnus (Rhamnus alaternus) is an environmental weed on the Inner Hauraki Gulf Islands, Auckland. The species has densely colonised coastal slopes of Motutapu Island and invaded unique Metrosideros forest on Rangitoto Island. It can develop dense leafy canopies under which no other plants grow. If left unhindered, rhamnus is likely to smother areas reserved for reforestation in a large restoration programme on Motutapu Island, and progressively replace native plants on Rangitoto Island. Ample seed dispersal of rhamnus is facilitated by common frugivorous birds. Spread of the species is restricted by stock grazing and rabbit browsing, but was probably recently enhanced by the removal of large numbers of possums and wallabies from Motutapu and Rangitoto Islands. Keywords: Rhamnus alaternus; Auckland; Inner Hauraki Gulf; Motutapu Island; Rangitoto Island; weed impact; weed dispersal; browse pressure; weed control strategy. INTRODUCTION Rhamnus (Rhamnus alaternus) also called evergreen, or Italian buckthorn, is a small Mediterranean evergreen tree (Zohary 1962, Tutin et al. 1968, Di Castri 1981). It was sold in New Zealand last century (Hay's Annual Garden Book 1872), but this seems to have been discontinued, as rhamnus is generally not well known as a garden plant in New Zealand today. Rhamnus has naturalised locally from Northland to Otago, particularly in coastal environments (Fromont 1995). The species has become a serious environmental weed in the Auckland Region mostly on the islands of the Inner Hauraki Gulf. -

Success of Translocations of Red-Fronted Parakeets

Conservation Evidence (2010) 7, 21-26 www.ConservationEvidence.com Success of translocations of red-fronted parakeets Cyanoramphus novaezelandiae novaezelandiae from Little Barrier Island (Hauturu) to Motuihe Island, Auckland, New Zealand Luis Ortiz-Catedral* & Dianne H. Brunton Ecology and Conservation Group, Institute of Natural Sciences, Massey University, Private Bag 102-904, Auckland, New Zealand * Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected] SUMMARY The red-fronted parakeet Cyanoramphus novaezelandiae is a vulnerable New Zealand endemic with a fragmented distribution, mostly inhabiting offshore islands free of introduced mammalian predators. Four populations have been established since the 1970s using captive-bred or wild-sourced individuals translocated to islands undergoing ecological restoration. To establish a new population in the Hauraki Gulf, North Island, a total of 31 parakeets were transferred from Little Barrier Island (Hauturu) to Motuihe Island in May 2008 and a further 18 in March 2009. Overall 55% and 42% of individuals from the first translocation were confirmed alive at 30 and 60 days post-release, respectively. Evidence of nesting and unassisted dispersal to a neighbouring island was observed within a year of release. These are outcomes are promising and indicate that translocation from a remnant wild population to an island free of introduced predators is a useful conservation tool to expand the geographic range of red-fronted parakeets. BACKGROUND mammalian predators and undergoing ecological restoration, Motuihe Island. The avifauna of New Zealand is presently considered to be the world’s most extinction- Little Barrier Island (c. 3,000 ha; 36 °12’S, prone (Sekercioglu et al. 2004). Currently, 77 175 °04’E) lies in the Hauraki Gulf of approximately 280 extant native species are approximately 80 km north of Auckland City considered threatened of which approximately (North Island), and is New Zealand’s oldest 30% are listed as Critically Endangered wildlife reserve, established in 1894 (Cometti (Miskelly et al. -

Maori Cartography and the European Encounter

14 · Maori Cartography and the European Encounter PHILLIP LIONEL BARTON New Zealand (Aotearoa) was discovered and settled by subsistence strategy. The land east of the Southern Alps migrants from eastern Polynesia about one thousand and south of the Kaikoura Peninsula south to Foveaux years ago. Their descendants are known as Maori.1 As by Strait was much less heavily forested than the western far the largest landmass within Polynesia, the new envi part of the South Island and also of the North Island, ronment must have presented many challenges, requiring making travel easier. Frequent journeys gave the Maori of the Polynesian discoverers to adapt their culture and the South Island an intimate knowledge of its geography, economy to conditions different from those of their small reflected in the quality of geographical information and island tropical homelands.2 maps they provided for Europeans.4 The quick exploration of New Zealand's North and The information on Maori mapping collected and dis- South Islands was essential for survival. The immigrants required food, timber for building waka (canoes) and I thank the following people and organizations for help in preparing whare (houses), and rocks suitable for making tools and this chapter: Atholl Anderson, Canberra; Barry Brailsford, Hamilton; weapons. Argillite, chert, mata or kiripaka (flint), mata or Janet Davidson, Wellington; John Hall-Jones, Invercargill; Robyn Hope, matara or tuhua (obsidian), pounamu (nephrite or green Dunedin; Jan Kelly, Auckland; Josie Laing, Christchurch; Foss Leach, stone-a form of jade), and serpentine were widely used. Wellington; Peter Maling, Christchurch; David McDonald, Dunedin; Bruce McFadgen, Wellington; Malcolm McKinnon, Wellington; Marian Their sources were often in remote or mountainous areas, Minson, Wellington; Hilary and John Mitchell, Nelson; Roger Neich, but by the twelfth century A.D. -

Evaluating the Progress of Restoration Planting on Motutapu Island, New Zealand

University of Auckland, 2015 Evaluating the progress of restoration planting on Motutapu Island, New Zealand Robert Vennell1* 1 University of Auckland, Private Bag 92019, Auckland 1142, New Zealand * Email for correspondence: [email protected] Introduction Ecological restoration is an intentional human activity that attempts to accelerate the recovery of an ecosystem that has become degraded, damaged or destroyed (SER, 2004). Often the impacts to ecosystems are so great that they cannot recover to their ecological state prior to the disturbance (SER, 2004; Suding et al. 2004). Therefore the key focus of most restoration efforts is to return ecosystems back to their historic trajectories (SER, 2004; Forbes & Craig, 2013) in order to enhance their overall health, integrity and sustainability. In order to achieve this goal, a historic reference state is generally used as a framework and to provide a starting point for designing the restoration (Balauger et al. 2012). There is concern however that we currently lack sufficient knowledge of historic ecosystems to replicate their composition and function faithfully (Davis, 2000; Choi et al. 2007). In order to mitigate this problem, a modern analogue is often used – the reference ecosystem (SER, 2004). This consists of a contemporary habitat that is assumed to representative of the desired historic reference state, and can serve as a model that restoration activities attempt to emulate (White & Walker, 1997). As a result it also provides an ideal opportunity for evaluating the success of restoration activities, allowing comparisons to be made against restored ecosystems and outcomes effectively measured (e.g. Stephenson, 1999; Palmer et al. 2005; Klein et al. -

District Plan

36 PART 12 APPENDICES CITY OF AUCKLAND - DISTRICT PLAN HAURAKI GULF ISLANDS SECTION - OPERATIVE 1996 Page 1 updated 07/06/2011 CITY OF AUCKLAND - DISTRICT PLAN Page 2 HAURAKI GULF ISLANDS SECTION - OPERATIVE 1996 updated 07/06/2011 APPENDICES CONTENTS.................................................................................................. PAGE APPENDIX A - PROHIBITED ACTIVITIES................................................4 APPENDIX B - SCHEDULE OF PROTECTED ITEMS..............................5 APPENDIX C - SITES OF ECOLOGICAL SIGNIFICANCE.....................13 APPENDIX D - RARE, THREATENED AND ENDEMIC SPECIES WITHIN THE HAURAKI GULF ISLANDS................................................24 APPENDIX E - WAIHEKE ISLAND - MOTUTAPU ISLAND RADIO PROTECTION CORRIDOR......................................................................26 APPENDIX F - SCHEDULE OF BUILDING RESTRICTION YARDS ......27 APPENDIX G - SCHEDULE OF DESIGNATED LAND............................28 APPENDIX H - WAIHEKE ISLAND AIRFIELDS LIMITED SCHEDULE OF CONDITIONS .....................................................................................38 APPENDIX I - CLARIS AIRPORT PROTECTION FANS.........................40 APPENDIX J - SECTIONS 7, 8 AND 9 OF THE HAURAKI GULF MARINE PARK ACT 2000 .......................................................................41 CITY OF AUCKLAND - DISTRICT PLAN HAURAKI GULF ISLANDS SECTION - OPERATIVE 1996 Page 3 updated 07/06/2011 APPENDIX A - PROHIBITED ACTIVITIES APPENDIX A - PROHIBITED ACTIVITIES The following listed activities -

Changes in the Wild Vascular Flora of Tiritiri Matangi Island, 1978–2010

AvailableCameron, on-line Davies: at: Vascular http://www.newzealandecology.org/nzje/ flora of Tiritiri Matangi 307 Changes in the wild vascular flora of Tiritiri Matangi Island, 1978–2010 Ewen K. Cameron1* and Neil C. Davies2 1Auckland War Memorial Museum, Private Bag 92018, Auckland, New Zealand 2Glenfield College, PO Box 40176, Glenfield 0747, Auckland, New Zealand *Author for correspondence (Email: [email protected]) Published online: 18 November 2013 Abstract: Tiritiri Matangi Island (‘Tiri’) in the Hauraki Gulf of the northern North Island of New Zealand was deforested, pastorally farmed, and then farming was abandoned in 1972. This history is typical of many northern New Zealand islands. The island’s modern history is less typical; since 1984 it has been the focus of a major restoration project involving thousands of volunteers. No original forest remains, but grazed secondary forest in a few valley bottoms covered about 20% of the island when farming was abandoned. Tiri’s wild vascular flora was recorded in the 1900s and again in the 1970s. From 2006–2010 we collated all past records, herbarium vouchers, and surveyed the island to produce an updated wild flora. Our results increase the known pre-1978 flora by 31% (adding 121 species, varieties and hybrids). A further six species are listed as known only from the seed rain; 32 species as planted only; and one previous wild record is rejected. These last three decades have seen major changes on the island: the eradication of the exotic seed predator Pacific rat, Rattus exulans, in 1993; the planting of about 280,000 native trees and shrubs during 1984–94 as part of a major restoration project along with a massive increase in human visitation; and the successful translocation of 11 native bird species and three native reptile species. -

Rangitoto National Park Rewild Opportunity

Rangitoto National Park Rewild opportunity Inspiring our community to rewild this place The Opportunity Context Floating in Auckland’s front garden, Rangitoto, These motu were recognized as part of the Motutapu, Motuihe/Te motu-a-Ihenga, and Hauraki Gulf Maritime Park for a period after Browns Island (Motukorea), are predator-free 1967. motu (islands) that will flourish when native There are plans to rewild larger areas of these forest is thriving on them all. motu but the timeframe is long. With current Rangtitoto motu contains the world’s largest and projected employment needs, there is a pohutukawa forest. The other 3 motu pastoral wonderful opportunity to rewild now, to attain areas are ideal for rewilding of native forest, immediate ecological and social value. wetlands/streams and coastal ecology. Some Some areas of WWII development and roads planting by volunteers has already been started on Rangitoto could also be rewilded. on Motuihe and Motutapu. The motu are important ecological stepping The motu are also nationally important coastal stones within the Hauraki Gulf motu, and and volcanic landscapes, visitor destinations, between the Hunua Ranges, eastern Auckland, land environments and geopreservation sites. and some of the other maunga of Auckland The conferring of National Park status would that the iwi plans to rewild. recognize these nationally important values, These motu are also host to a variety of with all the benefits that rewilding can create. nationally important native species; Plants – shore spurge, shore buttercup, kohihi, pinaki, Kirk’s tree daisy Birds – little spotted kiwi, Current Management North Island brown kiwi, saddleback, takahe, shore plover, brown teal, northern NZ dotterel, Most parts of these motu are managed by DOC whitehead, little blue penguin Reptiles – as Scenic and Recreation Reserves, which were tuatara, Dauvacel’s gecko. -

The Rangitoto and Motutapu Pest Eradication - a Feasibility Study

The Rangitoto and Motutapu Pest Eradication - A Feasibility Study SEPTEMBER 2008 The Rangitoto and Motutapu Pest Eradication A Feasibility Study Richard Griffiths and David Towns SEPTEMBER 2008 Published by Department of Conservation Auckland Conservancy Private Bag 68-508, Newton, Auckland New Zealand Cover: Rangitoto looking from Motutapu Photo: DOC © Copyright September 2008, New Zealand Department of Conservation ISBN 978-0-478-14494-9 (hardcopy) ISBN 978-0-478-14495-6 (web PDF) ISBN 978-0-478-14496-3 (HTML) File: NHT 02-17-01-18 In the interest of forest conservation, DOC Science Publishing supports paperless electronic publishing. When printing, recycled paper is used wherever possible. Executive Summary The eradication of the seven remaining animal pest species remaining on Rangitoto and Motutapu was announced by the Prime Minister and Minister of Conservation in June 2006. With stoats, cats, hedgehogs, rabbits, mice and two species of rats spread across an area of 3842ha, the proposed project is the most challenging and complex island pest eradication the Department of Conservation (DOC) has ever attempted. To better understand the scale and complexity of the project, a feasibility study was undertaken. This study considered the ecological, economic and social context of the project to allow an informed decision to be made on whether or not to commit resources to further eradication planning. This document outlines the findings of the feasibility study and concludes that while a number of contingencies exist within the project, the proposed eradication is not only feasible, but has many significant benefits. No single precedent exists on which this project can be modelled and information from a wide range of sources has been required. -

PREHISTORIC PA SITES of METROPOLITAN AUCKLAND by Bruce W. Hayward SUMMARY One Hundred and Ninety-Eight Prehistoric Pa (=Forts) A

TANE 29, 1983 PREHISTORIC PA SITES OF METROPOLITAN AUCKLAND by Bruce W. Hayward New Zealand Geological Survey, P. O. Box 30368, Lower Hutt SUMMARY One hundred and ninety-eight prehistoric pa (=forts) are known from the Auckland metropolitan area and over half of these have traceable Maori names. At least 20% of the sites have been completely destroyed and another 20% have suffered extensive damage caused by land ploughing, urban sprawl, quarrying, public works and marine erosion. Most pa in the area were built between 1450 and 1830, with the majority probably constructed during the late 16th to early 18th centuries when the area had its largest prehistoric population. Distribution of pa sites reflects the distribution of the prehistoric population. Inland pa are clustered around Auckland's volcanoes where extensive gardens were established on the rich volcanic soils. Others are associated with smaller gardens on the islands of the inner Hauraki Gulf and the lower valleys on the west coast of the Waitakere Ranges. Coastal pa were built along most shorelines with a notable exception being the western and southern shores of the inner Waitemata Harbour. The pa sites are classified as: 1. Volcanic hill pa - large sites with extensively terraced slopes and upper portion often fortified with pallisades; sometimes a few ditch defences across crater rims. 2. Ridge and hill pa - moderate-sized sites, often with ditch and bank defences on 1 or 2 sides. 3. Coastal headland pa - small to moderate size, usually with ditch defences across the landward side. 4. Clifftop pa - small size, naturally cliffed defences on one side with other 3 sides ringed with ditch and bank defences. -

Island Operating Procedure (IOP): Rangitoto and Motutapu Islands

Rangitoto and Motutapu Islands: Island Operating Procedure (IOP) v. October 2019 Table of Contents Foreword.............................................................................................................................. 5 Part 1 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 7 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................ 7 1.1. Terminology ............................................................................................... 7 1.2. Purpose ..................................................................................................... 7 1.3. Scope ........................................................................................................ 7 1.4. Legal Compliance ...................................................................................... 7 1.5. Mana Whenua ........................................................................................... 7 1.6. Overall Control ........................................................................................... 7 1.7. Day to Day Management and Control ........................................................ 7 Part 2 Biosecurity, Health and Safety ................................................................................ 8 2. Biosecurity ................................................................................................................. 8 2.1. Compliance ............................................................................................... -

Annual Report 2017 2018 Kiwis for Kiwi Is a National Charity That Works in Partnership with the Department of Conservation to Protect Kiwi and Increase Their Numbers

Annual Report 2017 2018 Kiwis for kiwi is a national charity that works in partnership with the Department of Conservation to protect kiwi and increase their numbers. Our role is to work with community- and iwi-led kiwi conservation groups to achieve the national goal of 2% growth of all kiwi species. We do this by raising and distributing funds to projects providing safe habitat, and growing more kiwi in k ohanga- sites for release to predator-controlled areas in the wild. Our vision: To take kiwi from endangered to everywhere. Our purpose: To ensure the long-term sustainability and growth of our kiwi populations. 2 Kiwis for kiwi Annual Report 2017 - 2018 Cover image © Neil Hutton Rongomai ahua, the first chick to be released onto Motutapu Island as part of Kiwis for kiwi’s new strategy, being introduced to his new home by trustee Ruud Kleinpaste. © Bridget Winstone Kiwis for kiwi Annual Report 2017 - 2018 3 CHAIRMAN’S REVIEW The war on predators is fast becoming kiwi community groups, often volunteers, have been creating However, the Trust remains under-funded to complete the a nationwide movement. predator free habitats for years. The Trust has been very proud first stage of its recovery strategy in a timely fashion. We to support them and will continue to do so. need an additional $6m over the next five years to deliver the accelerated breeding programme. Without this funding, the Hundreds of community groups and literally thousands of But in terms of preserving the national kiwi population, we’ve programme will take much longer. -

Rangitoto Island Is a Pest-Free Island

sacred island RANGITOTO FERRY TIMES & FARES Travel time is WEEKDAYS WEEKENDS & approximately 25 minutes MOTUTAPU ISLAND from downtown Auckland PUBLIC HOLIDAYS RANGITOTO DEPARTS - 7. 30 am* AUCKLAND 9. 15 am 9. 15 am 10. 30 am 10. 30 am ISLAND 12. 15 pm 12. 15 pm *EARLY BIRD SAILING: ADULT $23 | CHILD $11.50 - 1. 30 pm APPROVED DEPARTS 9. 25 am 9. 25 am DEVONPORT 12. 25 pm 12. 25 pm ferry & tours Motutapu, which means Sacred Island, has a rich history dating back to DEPARTS - 8. 00 am*** the Jurassic period, and is one of the oldest islands in the Hauraki Gulf. RANGITOTO 12. 45 pm 12. 45 pm The island is home to historic Reid Homestead farm (1901), scenic walking 2. 30 p m** 2. 30 p m** **Sailing does not stop at Devonport 3. 30 pm 4. 00 pm tracks, World War II gun emplacements and spectacular views of the ***Sailing goes via Half Moon Bay Gulf. There are over 300 recorded Maori archaeological sites, including - 5. 00 pm distinctive pa sites, reflecting the vibrant life that existed on the island. RETURN FARES: A restoration project of over 500,000 native trees have been planted by ADULT $33 | CHILD $16.50 | FAMILY $89 volunteers of the Motutapu Restoration Trust to help renew the natural and BOOKINGS ARE RECOMMENDED. cultural landscape of Motutapu. Find out more, and how you can help at motutapu.org.nz MOTUTAPU & MOTUIHE FERRY TIMES & FARES WALK BETWEEN THE ISLANDS! SERVICE OPERATES ON THE FOLLOWING SUNDAYS The Motutapu ferry arrives/departs at Home Bay.