The Cinema of Hong Kong History, Arts, Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

See It Big! Action Features More Than 30 Action Movie Favorites on the Big

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ‘SEE IT BIG! ACTION’ FEATURES MORE THAN 30 ACTION MOVIE FAVORITES ON THE BIG SCREEN April 19–July 7, 2019 Astoria, New York, April 16, 2019—Museum of the Moving Image presents See It Big! Action, a major screening series featuring more than 30 action films, from April 19 through July 7, 2019. Programmed by Curator of Film Eric Hynes and Reverse Shot editors Jeff Reichert and Michael Koresky, the series opens with cinematic swashbucklers and continues with movies from around the world featuring white- knuckle chase sequences and thrilling stuntwork. It highlights work from some of the form's greatest practitioners, including John Woo, Michael Mann, Steven Spielberg, Akira Kurosawa, Kathryn Bigelow, Jackie Chan, and much more. As the curators note, “In a sense, all movies are ’action’ movies; cinema is movement and light, after all. Since nearly the very beginning, spectacle and stunt work have been essential parts of the form. There is nothing quite like watching physical feats, pulse-pounding drama, and epic confrontations on a large screen alongside other astonished moviegoers. See It Big! Action offers up some of our favorites of the genre.” In all, 32 films will be shown, many of them in 35mm prints. Among the highlights are two classic Technicolor swashbucklers, Michael Curtiz’s The Adventures of Robin Hood and Jacques Tourneur’s Anne of the Indies (April 20); Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai (April 21); back-to-back screenings of Mad Max: Fury Road and Aliens on Mother’s Day (May 12); all six Mission: Impossible films -

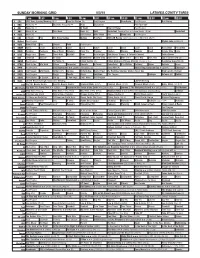

Sunday Morning Grid 5/3/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/3/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program NewsRadio Paid Program Bull Riding 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Equestrian PGA Tour Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Brooklyn Nets at Atlanta Hawks. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Pre-Race NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: GEICO 500. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Afghan Luke (2011) (R) 18 KSCI Breast Red Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Fresh Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Fast. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight Rick Steves’ Europe: A Cultural Carnival Father Brown 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Taxi › (2004) (PG-13) 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Pumas vs Azul República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program 101 Dalmatians ›› (1996) Glenn Close. -

OFFICIAL RECORD of PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 29

LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 29 April 2015 9455 OFFICIAL RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 29 April 2015 The Council met at Eleven o'clock MEMBERS PRESENT: THE PRESIDENT THE HONOURABLE JASPER TSANG YOK-SING, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ALBERT HO CHUN-YAN THE HONOURABLE LEE CHEUK-YAN THE HONOURABLE JAMES TO KUN-SUN THE HONOURABLE CHAN KAM-LAM, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE LEUNG YIU-CHUNG DR THE HONOURABLE LAU WONG-FAT, G.B.M., G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE EMILY LAU WAI-HING, J.P. THE HONOURABLE TAM YIU-CHUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ABRAHAM SHEK LAI-HIM, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE TOMMY CHEUNG YU-YAN, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE FREDERICK FUNG KIN-KEE, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE VINCENT FANG KANG, S.B.S., J.P. 9456 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL ─ 29 April 2015 THE HONOURABLE WONG KWOK-HING, B.B.S., M.H. PROF THE HONOURABLE JOSEPH LEE KOK-LONG, S.B.S., J.P., Ph.D., R.N. THE HONOURABLE JEFFREY LAM KIN-FUNG, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE ANDREW LEUNG KWAN-YUEN, G.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE WONG TING-KWONG, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CYD HO SAU-LAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE STARRY LEE WAI-KING, J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE LAM TAI-FAI, S.B.S., J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN HAK-KAN, J.P. THE HONOURABLE CHAN KIN-POR, B.B.S., J.P. DR THE HONOURABLE PRISCILLA LEUNG MEI-FUN, S.B.S., J.P. -

Bullet in the Head

JOHN WOO’S Bullet in the Head Tony Williams Hong Kong University Press The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © Tony Williams 2009 ISBN 978-962-209-968-5 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Condor Production Ltd., Hong Kong, China Contents Series Preface ix Acknowledgements xiii 1 The Apocalyptic Moment of Bullet in the Head 1 2 Bullet in the Head 23 3 Aftermath 99 Appendix 109 Notes 113 Credits 127 Filmography 129 1 The Apocalyptic Moment of Bullet in the Head Like many Hong Kong films of the 1980s and 90s, John Woo’s Bullet in the Head contains grim forebodings then held by the former colony concerning its return to Mainland China in 1997. Despite the break from Maoism following the fall of the Gang of Four and Deng Xiaoping’s movement towards capitalist modernization, the brutal events of Tiananmen Square caused great concern for a territory facing many changes in the near future. Even before these disturbing events Hong Kong’s imminent return to a motherland with a different dialect and social customs evoked insecurity on the part of a population still remembering the violent events of the Cultural Revolution as well as the Maoist- inspired riots that affected the colony in 1967. -

Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5pg3z8fg Author Chien, Irene Y. Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames by Irene Yi-Jiun Chien A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media and the Designated Emphasis in New Media in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Linda Williams, Chair Professor Kristen Whissel Professor Greg Niemeyer Professor Abigail De Kosnik Spring 2015 Abstract Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames by Irene Yi-Jiun Chien Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media Designated Emphasis in New Media University of California, Berkeley Professor Linda Williams, Chair Programmed Moves examines the intertwined history and transnational circulation of two major videogame genres, martial arts fighting games and rhythm dancing games. Fighting and dancing games both emerge from Asia, and they both foreground the body. They strip down bodily movement into elemental actions like stepping, kicking, leaping, and tapping, and make these the form and content of the game. I argue that fighting and dancing games point to a key dynamic in videogame play: the programming of the body into the algorithmic logic of the game, a logic that increasingly organizes the informatic structure of everyday work and leisure in a globally interconnected information economy. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION The wuxia film is the oldest genre in the Chinese cinema that has remained popular to the present day. Yet despite its longevity, its history has barely been told until fairly recently, as if there was some force denying that it ever existed. Indeed, the genre was as good as non-existent in China, its country of birth, for some fifty years, being proscribed over that time, while in Hong Kong, where it flowered, it was gen- erally derided by critics and largely neglected by film historians. In recent years, it has garnered a following not only among fans but serious scholars. David Bordwell, Zhang Zhen, David Desser and Leon Hunt have treated the wuxia film with the crit- ical respect that it deserves, addressing it in the contexts of larger studies of Hong Kong cinema (Bordwell), the Chinese cinema (Zhang), or the generic martial arts action film and the genre known as kung fu (Desser and Hunt).1 In China, Chen Mo and Jia Leilei have published specific histories, their books sharing the same title, ‘A History of the Chinese Wuxia Film’ , both issued in 2005.2 This book also offers a specific history of the wuxia film, the first in the English language to do so. It covers the evolution and expansion of the genre from its beginnings in the early Chinese cinema based in Shanghai to its transposition to the film industries in Hong Kong and Taiwan and its eventual shift back to the Mainland in its present phase of development. Subject and Terminology Before beginning this history, it is necessary first to settle the question ofterminology , in the process of which, the characteristics of the genre will also be outlined. -

Redirected from Films Considered the Greatest Ever) Page Semi-Protected This List Needs Additional Citations for Verification

List of films considered the best From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from Films considered the greatest ever) Page semi-protected This list needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be chall enged and removed. (November 2008) While there is no general agreement upon the greatest film, many publications an d organizations have tried to determine the films considered the best. Each film listed here has been mentioned in a notable survey, whether a popular poll, or a poll among film reviewers. Many of these sources focus on American films or we re polls of English-speaking film-goers, but those considered the greatest withi n their respective countries are also included here. Many films are widely consi dered among the best ever made, whether they appear at number one on each list o r not. For example, many believe that Orson Welles' Citizen Kane is the best mov ie ever made, and it appears as #1 on AFI's Best Movies list, whereas The Shawsh ank Redemption is #1 on the IMDB Top 250, whilst Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back is #1 on the Empire magazine's Top 301 List. None of the surveys that produced these citations should be viewed as a scientif ic measure of the film-watching world. Each may suffer the effects of vote stack ing or skewed demographics. Internet-based surveys have a self-selected audience of unknown participants. The methodology of some surveys may be questionable. S ometimes (as in the case of the American Film Institute) voters were asked to se lect films from a limited list of entries. -

June 2010 Newsletter

June 2010 – Volume 2, Issue 6 THE DRAGON’S LAIR NEWSLETTER OF THE IRON DRAGON KUNG FU AND KICKBOXING CLUB 91 STATION STREET, UNIT 8, AJAX, ONTARIO L1S 3H2 June 2010 VOLUME 2, ISSUE 6 (905) 427-7370 / [email protected] / www.iron-dragon.ca COMMENTARY As I sit here writing this newsletter in the sweltering heat of an amazing Victoria Day weekend I am overcome by a sense of nostalgia. Can it be that the Bruce Lee film “Enter the Dragon” was released some 37 years ago?!!! It was a trip down memory lane as I prepared the articles related to that film! I will be thrilled if just one of my students discovers this film for the very first time! June 2010 will prove to be a milestone in the competitive aspirations of our club. We have no fewer than 5 competitive events scheduled this month! Our fighter Shawn Nanay will be fighting for an unprecedented 3 times in one month! Our Lil and Young Dragons are competing in the Canada Cup Continuous Sparring Competition and Julian Dias, Chris DiGiovanni and Kevin Lee will be fighting in the Ontario Jiu Jitsu Championships. Competitions in 3 disciplines – Kickboxing , Continuous Fighting and Grappling all in one month!!! We have come a long, long way baby! MARTIAL ARTS IN THE MEDIA “Enter the Dragon” – Bruce Lee’s film masterpiece Enter the Dragon was a groundbreaking film that was released in North America in the summer of 1973, shortly after the death of its star, Bruce Lee. The release of this film was the highlight of the Kung Fu Mania that swept the North American continent in the early 1970’s. -

Episode 289 – Talking Sammo Hung | Whistlekickmartialartsradio.Com

Episode 289 – Talking Sammo Hung | whistlekickMartialArtsRadio.com Jeremy Lesniak: Hey there, thanks for tuning in. Welcome, this is whistlekick martial arts radio and today were going to talk all about the man that I believe is the most underrated martial arts actor of today, possibly of all time, Sammo Hung. If you're new to the show you may not know my voice I'm Jeremy Lesniak, I'm the founder of whistlekick we make apparel and sparring gear and training aids and we produce things like this show. I wanna thank you for stopping by, if you want to check out the show notes for this or any of the other episodes we've done, you can find those over at whistlekickmartialartsradio.com. You find our products at whistlekick.com or on Amazon or maybe if you're one of the lucky ones, at your martial arts school because we do offer wholesale accounts. Thank you to everyone who has supported us through purchases and even if you aren’t wearing a whistlekick shirt or something like that right now, thank you for taking the time out of your day to listen to this episode. As I said, here on today's episode, were talking about one of the most respected martial arts actor still working today, a man who has been active in the film industry for almost 60 years. None other the Sammo Hung. Also known as Hung Kam Bow i'll admit my pronunciation is not always the best I'm doing what I can. Hung originates from Hong Kong where he is known not only as an actor but also as an action choreographer, producer, and director. -

Do You Know Bruce Was Known by Many Names?

Newspapers In Education and the Wing Luke Museum of the Asian Pacific American Experience present ARTICLE 2 DO YOU KNOW BRUCE WAS KNOWN BY MANY NAMES? “The key to immortality is living a life worth remembering.”—Bruce Lee To have one English name and one name in your family’s mother tongue is common Bruce began teaching and started for second and third generation Asian Americans. Bruce Lee had two names as well as his first school here in Seattle, on a number of nicknames he earned throughout his life. His Chinese name was given to Weller Street, and then moved it to him by his parents at birth, while it is said that a nurse at the hospital in San Francisco its more prominent location in the where he was born gave him his English name. While the world knows him primarily University District. From Seattle as Bruce Lee, he was born Lee Jun Fan on November 27, 1940. he went on to open schools in Oakland and Los Angeles, earning Bruce Lee’s mother gave birth to him in the Year of the Dragon during the Hour of the him the respectful title of “Sifu” by Dragon. His Chinese given name reflected her hope that Bruce would return to and be his many students which included Young Bruce Lee successful in the United States one day. The name “Lee Jun Fan” not only embodied the likes of Steve McQueen, James TM & (C) Bruce Lee Enterprises, LLC. All Rights Reserved. his parents’ hopes and dreams for their son, but also for a prosperous China in the Coburn, Kareem Abdul Jabbar, www.brucelee.com modern world. -

Cultural Representation in Bruce Lee's the Way of the Dragon Min

Confronting Orientalism with Cinematic Art: Cultural Representation in Bruce Lee’s The Way of the Dragon Min-Hua Wu http://benz.nchu.edu.tw/~intergrams/intergrams/162/162-wu.pdf ISSN: 1683-4186 Abstract Taking Edward Said’s discourse on Orientalism as a point of departure, this paper attempts to explore how Bruce Lee confronts Orientalism with cinematic art. It analyzes one of Lee’s representative films, The Way of the Dragon, examining how the director manipulates traditional kung fu cameras to subvert stereotypical cultural representations. In this unique action film, he makes the best of Chinese kung fu while appealing to the art of Western filmmaking, where—as an actor and director— he strives to screen against and beyond occidental stereotypes. As a result, he transforms a Western mythology into an Asian heroic myth and tinges the theory and practice of his kung fu formation with a Gramscian hegemonic vein in a sophisticated manner. This study also discusses audience receptions of Lee’s cinematic representations based on Stuart Hall’s encoding-decoding model for cultural analysis. From Lee’s brand new perspective, the audience witnesses that an Oriental nobody dares to go so far as to stand up against Orientalism and manage to defy Western sweeping generalizations of the Orient. The film thus rewrites the stereotypical discourse that portrays the so- called Chinaman as affected and not effective. Presenting a firm Chinese subjectivity by means of kung fu fightings on the stage and in the limelight, Lee succeeds in asserting himself as an important international cinematic figure who in one sense or another utters the unutterable suppressed inner voices for the Chinese people, the Oriental, and all those who belong to the marginal. -

Download Heroic Grace: the Chinese Martial Arts Film Catalog (PDF)

UCLA Film and Television Archive Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office in San Francisco HEROIC GRACE: THE CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FILM February 28 - March 16, 2003 Los Angeles Front and inside cover: Lau Kar-fai (Gordon Liu Jiahui) in THE 36TH CHAMBER OF SHAOLIN (SHAOLIN SANSHILIU FANG ) present HEROIC GRACE: THE CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FILM February 28 - March 16, 2003 Los Angeles Heroic Grace: The Chinese Martial Arts Film catalog (2003) is a publication of the UCLA Film and Television Archive, Los Angeles, USA. Editors: David Chute (Essay Section) Cheng-Sim Lim (Film Notes & Other Sections) Designer: Anne Coates Printed in Los Angeles by Foundation Press ii CONTENTS From the Presenter Tim Kittleson iv From the Presenting Sponsor Annie Tang v From the Chairman John Woo vi Acknowledgments vii Leaping into the Jiang Hu Cheng-Sim Lim 1 A Note on the Romanization of Chinese 3 ESSAYS Introduction David Chute 5 How to Watch a Martial Arts Movie David Bordwell 9 From Page to Screen: A Brief History of Wuxia Fiction Sam Ho 13 The Book, the Goddess and the Hero: Sexual Bérénice Reynaud 18 Aesthetics in the Chinese Martial Arts Film Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon—Passing Fad Stephen Teo 23 or Global Phenomenon? Selected Bibliography 27 FILM NOTES 31-49 PROGRAM INFORMATION Screening Schedule 51 Print & Tape Sources 52 UCLA Staff 53 iii FROM THE PRESENTER Heroic Grace: The Chinese Martial Arts Film ranks among the most ambitious programs mounted by the UCLA Film and Television Archive, taking five years to organize by our dedicated and intrepid Public Programming staff.