Martial Arts Cinema and Hong Kong Modernity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Brief Analysis of China's Contemporary Swordsmen Film

ISSN 1923-0176 [Print] Studies in Sociology of Science ISSN 1923-0184 [Online] Vol. 5, No. 4, 2014, pp. 140-143 www.cscanada.net DOI: 10.3968/5991 www.cscanada.org A Brief Analysis of China’s Contemporary Swordsmen Film ZHU Taoran[a],* ; LIU Fan[b] [a]Postgraduate, College of Arts, Southwest University, Chongqing, effects and packaging have made today’s swordsmen China. films directed by the well-known directors enjoy more [b]Associate Professor, College of Arts, Southwest University, Chongqing, China. personalized and unique styles. The concept and type of *Corresponding author. “Swordsmen” begin to be deconstructed and restructured, and the swordsmen films directed in the modern times Received 24 August 2014; accepted 10 November 2014 give us a wide variety of possibilities and ways out. No Published online 26 November 2014 matter what way does the directors use to interpret the swordsmen film in their hearts, it injects passion and Abstract vitality to China’s swordsmen film. “Chivalry, Military force, and Emotion” are not the only symbols of the traditional swordsmen film, and heroes are not omnipotent and perfect persons any more. The current 1. TSUI HARK’S IMAGINARY Chinese swordsmen film could best showcase this point, and is undergoing criticism and deconstruction. We can SWORDSMEN FILM see that a large number of Chinese directors such as Tsui Tsui Hark is a director who advocates whimsy thoughts Hark, Peter Chan, Xu Haofeng , and Wong Kar-Wai began and ridiculous ideas. He is always engaged in studying to re-examine the aesthetics and culture of swordsmen new film technology, indulging in creating new images and film after the wave of “historic costume blockbuster” in new forms of film, and continuing to provide audiences the mainland China. -

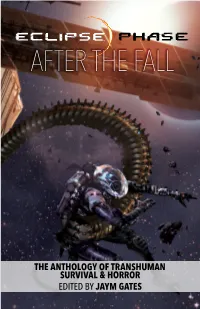

Eclipse Phase: After the Fall

AFTER THE FALL In a world of transhuman survival and horror, technology allows the re-shaping of bodies and minds, but also creates opportunities for oppression and puts the capa- AFTER THE FALL bility for mass destruction in the hands of everyone. Other threats lurk in the devastated habitats of the Fall, dangers both familiar and alien. Featuring: Madeline Ashby Rob Boyle Davidson Cole Nathaniel Dean Jack Graham Georgina Kamsika SURVIVAL &SURVIVAL HORROR Ken Liu OF ANTHOLOGY THE Karin Lowachee TRANSHUMAN Kim May Steven Mohan, Jr. Andrew Penn Romine F. Wesley Schneider Tiffany Trent Fran Wilde ECLIPSE PHASE 21950 Advance THE ANTHOLOGY OF TRANSHUMAN Reading SURVIVAL & HORROR Copy Eclipse Phase created by Posthuman Studios EDITED BY JAYM GATES Eclipse Phase is a trademark of Posthuman Studios LLC. Some content licensed under a Creative Commons License (BY-NC-SA); Some Rights Reserved. © 2016 AFTER THE FALL In a world of transhuman survival and horror, technology allows the re-shaping of bodies and minds, but also creates opportunities for oppression and puts the capa- AFTER THE FALL bility for mass destruction in the hands of everyone. Other threats lurk in the devastated habitats of the Fall, dangers both familiar and alien. Featuring: Madeline Ashby Rob Boyle Davidson Cole Nathaniel Dean Jack Graham Georgina Kamsika SURVIVAL &SURVIVAL HORROR Ken Liu OF ANTHOLOGY THE Karin Lowachee TRANSHUMAN Kim May Steven Mohan, Jr. Andrew Penn Romine F. Wesley Schneider Tiffany Trent Fran Wilde ECLIPSE PHASE 21950 THE ANTHOLOGY OF TRANSHUMAN SURVIVAL & HORROR Eclipse Phase created by Posthuman Studios EDITED BY JAYM GATES Eclipse Phase is a trademark of Posthuman Studios LLC. -

Bullet in the Head

JOHN WOO’S Bullet in the Head Tony Williams Hong Kong University Press The University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © Tony Williams 2009 ISBN 978-962-209-968-5 All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Condor Production Ltd., Hong Kong, China Contents Series Preface ix Acknowledgements xiii 1 The Apocalyptic Moment of Bullet in the Head 1 2 Bullet in the Head 23 3 Aftermath 99 Appendix 109 Notes 113 Credits 127 Filmography 129 1 The Apocalyptic Moment of Bullet in the Head Like many Hong Kong films of the 1980s and 90s, John Woo’s Bullet in the Head contains grim forebodings then held by the former colony concerning its return to Mainland China in 1997. Despite the break from Maoism following the fall of the Gang of Four and Deng Xiaoping’s movement towards capitalist modernization, the brutal events of Tiananmen Square caused great concern for a territory facing many changes in the near future. Even before these disturbing events Hong Kong’s imminent return to a motherland with a different dialect and social customs evoked insecurity on the part of a population still remembering the violent events of the Cultural Revolution as well as the Maoist- inspired riots that affected the colony in 1967. -

Sungkyun Journal of East Asian Studies

Sungkyun Journal of East Asian Studies On the Rooftop: A Study of Marginalized Youth Films in Hong Kong Cinema Xuelin ZHOU University of Auckland Sungkyun Journal of East Asian Studies. Vol. 8, No. 2 ⓒ 2008 Academy of East Asia Studies. pp.163-177 You may use content in the SJEAS back issues only for your personal, non-commercial use. Contents of each article do not represent opinions of SJEAS. Sungkyun Journal of East Asian Studies. Vol.8, No.2. � 2008 Academy of East Asian Studies. pp.163-177 On the Rooftop: A Study of Marginalized Youth Films in Hong Kong Cinema1 Xuelin ZHOU University of Auckland ABSTRACT Researchers of contemporary Hong Kong cinema have tended to concentrate on the monumental, metropolitan and/or historical works of such esteemed directors as Wong Kar-Wai, John Woo and Tsui Hark. This paper focuses instead on a number of low-budget films that circulated below the radar of Chinese as well as Western film scholars but were important to local young viewers, i.e. a cluster of films that feature deviant and marginalized youth as protagonists. They are very interesting as evidence of perceived social problems in contemporary Hong Kong. The paper aims to outline some main features of these marginalized youth films produced since the mid-1990s. Keywords: Hong Kong, cinema, youth culture, youth film, marginalized youth On the Rooftop A scene set on the rooftop of a skyscraper in central Hong Kong appears in New Police Story(2004), or Xin jingcha gushi, by the Hong Kong director Benny Chan, an action drama that features an aged local police officer struggling to fight a group of trouble-making, tech-savvy teenagers.2 The young people are using the rooftop for an “X-party,” an occasion for showing off their skills of skateboarding and cycling, by doing daredevil stunts along the edge of the building. -

Gender and the Family in Contemporary Chinese-Language Film Remakes

Gender and the family in contemporary Chinese-language film remakes Sarah Woodland BBusMan., BA (Hons) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2016 School of Languages and Cultures 1 Abstract This thesis argues that cinematic remakes in the Chinese cultural context are a far more complex phenomenon than adaptive translation between disparate cultures. While early work conducted on French cinema and recent work on Chinese-language remakes by scholars including Li, Chan and Wang focused primarily on issues of intercultural difference, this thesis looks not only at remaking across cultures, but also at intracultural remakes. In doing so, it moves beyond questions of cultural politics, taking full advantage of the unique opportunity provided by remakes to compare and contrast two versions of the same narrative, and investigates more broadly at the many reasons why changes between a source film and remake might occur. Using gender as a lens through which these changes can be observed, this thesis conducts a comparative analysis of two pairs of intercultural and two pairs of intracultural films, each chapter highlighting a different dimension of remakes, and illustrating how changes in gender representations can be reflective not just of differences in attitudes towards gender across cultures, but also of broader concerns relating to culture, genre, auteurism, politics and temporality. The thesis endeavours to investigate the complexities of remaking processes in a Chinese-language cinematic context, with a view to exploring the ways in which remakes might reflect different perspectives on Chinese society more broadly, through their ability to compel the viewer to reflect not only on the past, by virtue of the relationship with a source text, but also on the present, through the way in which the remake reshapes this text to address its audience. -

Download Download

Singapore Sidebar: Erotic Cinema By Toh, Hai Leong Fall 2004 Issue of KINEMA SIFF SIDEBAR: EROTIC CINEMA OF LI HAN HSIANG AND CHU YUAN The legendary directors, Li Han Hsiang and Chu Yuan, made chamber period films in the 1970s for the Shaw Studios in Hong Kong, helmed by the famous Shanghainese brothers Run Run and Runme. Those of us who lived through this period would remember it as prolific time of Hong Kong-made erotica. Films such as the 1973 Illicit Desire (Li Han Hsiang), which featured nudity, were routinely advertised in cinema trailers but were never shown intact. Singapore International Film Festival assembled several landmark erotic works from this period and showed them in the city for the first time on film, and uncut. The Chinese Courtesan films, a gentler but more fatalistic vision of producer Runme Shaw, began withChu Yuan’s first pugilistic - erotic masterpiece, Intimate Confessions Of A Chinese Courtesan (1972). It is the story of an older woman, Lady Chun, who loves her younger charge, Ai Nu (played with cold, distant sexual charisma by Lily Ho, one of Shaw’s beauty legends). This was Hong Kong’s first film with lesbianism as its theme. Chu Yuan pulls out all the stops in this film and the melding of the martial arts and erotic film is near perfect. As the madam of a brothel, Lady Chun hates men but kidnaps young girlstoworkas prostitutes for her. When Ai Nu (literally translated as love slave) is introduced to the brothel, Lady Chun is attracted by her defiance, and sees herself in her. -

Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5pg3z8fg Author Chien, Irene Y. Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames by Irene Yi-Jiun Chien A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media and the Designated Emphasis in New Media in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Linda Williams, Chair Professor Kristen Whissel Professor Greg Niemeyer Professor Abigail De Kosnik Spring 2015 Abstract Programmed Moves: Race and Embodiment in Fighting and Dancing Videogames by Irene Yi-Jiun Chien Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Media Designated Emphasis in New Media University of California, Berkeley Professor Linda Williams, Chair Programmed Moves examines the intertwined history and transnational circulation of two major videogame genres, martial arts fighting games and rhythm dancing games. Fighting and dancing games both emerge from Asia, and they both foreground the body. They strip down bodily movement into elemental actions like stepping, kicking, leaping, and tapping, and make these the form and content of the game. I argue that fighting and dancing games point to a key dynamic in videogame play: the programming of the body into the algorithmic logic of the game, a logic that increasingly organizes the informatic structure of everyday work and leisure in a globally interconnected information economy. -

Spectre, Connoting a Denied That This Was a Reference to the Earlier Films

Key Terms and Consider INTERTEXTUALITY Consider NARRATIVE conventions The white tuxedo intertextually references earlier Bond Behind Bond, image of a man wearing a skeleton mask and films (previous Bonds, including Roger Moore, have worn bone design on his jacket. Skeleton has connotations of Central image, protag- the white tuxedo, however this poster specifically refer- death and danger and the mask is covering up someone’s onist, hero, villain, title, ences Sean Connery in Goldfinger), providing a sense of identity, someone who wishes to remain hidden, someone star appeal, credit block, familiarity, nostalgia and pleasure to fans who recognise lurking in the shadows. It is quite easy to guess that this char- frame, enigma codes, the link. acter would be Propp’s villain and his mask that is reminis- signify, Long shot, facial Bond films have often deliberately referenced earlier films cent of such holidays as Halloween or Day of the Dead means expression, body lan- in the franchise, for example the ‘Bond girl’ emerging he is Bond’s antagonist and no doubt wants to kill him. This guage, colour, enigma from the sea (Ursula Andress in Dr No and Halle Berry in acts as an enigma code for theaudience as we want to find codes. Die Another Day). Daniel Craig also emerged from the sea out who this character is and why he wants Bond. The skele- in Casino Royale, his first outing as Bond, however it was ton also references the title of the film, Spectre, connoting a denied that this was a reference to the earlier films. ghostly, haunting presence from Bond’s past. -

From Free Cinema to British New Wave: a Story of Angry Young Men

SUPLEMENTO Ideas, I, 1 (2020) 51 From Free Cinema to British New Wave: A Story of Angry Young Men Diego Brodersen* Introduction In February 1956, a group of young film-makers premiered a programme of three documentary films at the National Film Theatre (now the BFI Southbank). Lorenza Mazzetti, Lindsay Anderson, Karel Reisz and Tony Richardson thought at the time that “no film can be too personal”, and vehemently said so in their brief but potent manifesto about Free Cinema. Their documentaries were not only personal, but aimed to show the real working class people in Britain, blending the realistic with the poetic. Three of them would establish themselves as some of the most inventive and irreverent British filmmakers of the 60s, creating iconoclastic works –both in subject matter and in form– such as Saturday Day and Sunday Morning, The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner and If… Those were the first significant steps of a New British Cinema. They were the Big Screen’s angry young men. What is British cinema? In my opinion, it means many different things. National cinemas are much more than only one idea. I would like to begin this presentation with this question because there have been different genres and types of films in British cinema since the beginning. So, for example, there was a kind of cinema that was very successful, not only in Britain but also in America: the films of the British Empire, the films about the Empire abroad, set in faraway places like India or Egypt. Such films celebrated the glory of the British Empire when the British Empire was almost ending. -

Unbelievable Bodies: Audience Readings of Action Heroines As a Post-Feminist Visual Metaphor

Unbelievable Bodies: Audience Readings of Action Heroines as a Post-Feminist Visual Metaphor Jennifer McClearen A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Washington 2013 Committee: Ralina Joseph, Chair LeiLani Nishime Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Communication ©Copyright 2013 Jennifer McClearen Running head: AUDIENCE READINGS OF ACTION HEROINES University of Washington Abstract Unbelievable Bodies: Audience Readings of Action Heroines as a Post-Feminist Visual Metaphor Jennifer McClearen Chair of Supervisory Committee: Associate Professor Ralina Joseph Department of Communication In this paper, I employ a feminist approach to audience research and examine the individual interviews of 11 undergraduate women who regularly watch and enjoy action heroine films. Participants in the study articulate action heroines as visual metaphors for career and academic success and take pleasure in seeing women succeed against adversity. However, they are reluctant to believe that the female bodies onscreen are physically capable of the action they perform when compared with male counterparts—a belief based on post-feminist assumptions of the limits of female physical abilities and the persistent representations of thin action heroines in film. I argue that post-feminist ideology encourages women to imagine action heroines as successful in intellectual arenas; yet, the ideology simultaneously disciplines action heroine bodies to render them unbelievable as physically powerful women. -

'The Whole Burden of Civilisation Has Fallen Upon Us'

‘The Whole Burden of Civilisation Has Fallen upon Us’. The Representation of Gender in Zombie Films, 1968-2013 Leon van Amsterdam Student number: s1141627 Leiden University MA History: Cities, Migration and Global Interdependence Thesis supervisor: Marion Pluskota 2 Contents Chapter 1: Introduction .............................................................................................................. 4 Theory ................................................................................................................................. 6 Literature Review ............................................................................................................... 9 Material ............................................................................................................................ 13 Method ............................................................................................................................. 15 Chapter 2: A history of the zombie and its cultural significance ............................................. 18 Race and gender representations in early zombie films .................................................. 18 The sci-fi zombie and Romero’s ghoulish zombie ............................................................ 22 The loss and return of social anxiety in the zombie genre .............................................. 26 Chapter 3: (Post)feminism in American politics and films ....................................................... 30 Protofeminism ................................................................................................................. -

Newsletter 34

Hong Kong Film Archive Quarterly 34 Newsletter 11.2005 Chor Yuen: A Lifetime in the Film Studio Three Glimpses of Takarada Akira Mirage Yellow Willow in the Frost 17 Editorial@ChatRoom English edition of Monographs of HK Film Veterans (3): Chor Yuen is to be released in April 2006. www.filmarchive.gov.hk Hong Kong Film Archive Head Angela Tong Section Heads Venue Mgt Rebecca Lam Takarada Akira danced his way in October. In November, Anna May Wong and Jean Cocteau make their entrance. IT Systems Lawrence Hui And comes January, films ranging from Cheung Wood-yau to Stephen Chow will be revisited in a retrospective on Acquisition Mable Ho Chor Yuen. Conservation Edward Tse Reviewing Chor Yuen’s films in recent months, certain scenes struck me as being uncannily familiar. I realised I Resource Centre Chau Yu-ching must have seen the film as a child though I couldn’t have known then that the director was Chor Yuen. But Research Wong Ain-ling coming to think of it, he did leave his mark on silver screen and TV alike for half a century. Tracing his work brings Editorial Kwok Ching-ling Programming Sam Ho to light how Cantonese and Mandarin cinema evolved into Hong Kong cinema. Today, in the light of the Chinese Winnie Fu film market and the need for Hong Kong cinema to reorient itself, his story about flowers sprouting from the borrowed seeds of Cantonese opera takes on special meaning. Newsletter I saw Anna May Wong for the first time during the test screening. The young artist was heart-rendering.