Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newsletter 34

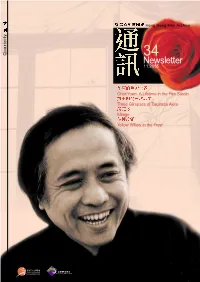

Hong Kong Film Archive Quarterly 34 Newsletter 11.2005 Chor Yuen: A Lifetime in the Film Studio Three Glimpses of Takarada Akira Mirage Yellow Willow in the Frost 17 Editorial@ChatRoom English edition of Monographs of HK Film Veterans (3): Chor Yuen is to be released in April 2006. www.filmarchive.gov.hk Hong Kong Film Archive Head Angela Tong Section Heads Venue Mgt Rebecca Lam Takarada Akira danced his way in October. In November, Anna May Wong and Jean Cocteau make their entrance. IT Systems Lawrence Hui And comes January, films ranging from Cheung Wood-yau to Stephen Chow will be revisited in a retrospective on Acquisition Mable Ho Chor Yuen. Conservation Edward Tse Reviewing Chor Yuen’s films in recent months, certain scenes struck me as being uncannily familiar. I realised I Resource Centre Chau Yu-ching must have seen the film as a child though I couldn’t have known then that the director was Chor Yuen. But Research Wong Ain-ling coming to think of it, he did leave his mark on silver screen and TV alike for half a century. Tracing his work brings Editorial Kwok Ching-ling Programming Sam Ho to light how Cantonese and Mandarin cinema evolved into Hong Kong cinema. Today, in the light of the Chinese Winnie Fu film market and the need for Hong Kong cinema to reorient itself, his story about flowers sprouting from the borrowed seeds of Cantonese opera takes on special meaning. Newsletter I saw Anna May Wong for the first time during the test screening. The young artist was heart-rendering. -

CHEUNG Wood-Yau 張活游(1910–1985.12.10)

CHEUNG Wood-yau 張活游(1910–1985.12.10) Actor A native of Meixian, Guangdong, Cheung was born in Guangzhou with the original name Cheung Kin-yu. Cheung made ends meet as a worker and theatre attendant before enrolling in the Cantonese Opera Actors Training School ran by The Chinese Artists Association in Guangzhou. Earning the recognition of Cantonese opera maestro Pak Yuk-tong, he became a principal actor upon graduation and had collaborated with celebrated opera artists such as Sit Kok-sin and Ma Si-tsang. He joined the Hong Kong film industry in 1939 and was immediately cast as the lead in his debut work, Breaking Through the Bronze Net (1939). Cheung later starred in over 20 titles, including Triple Flirtation of the White Chrysanthemum (1939), Grave of the Sisters-in-Law (1939), When Will You Return? (1940) and Love in Another Life (1941); and became a well-known actor before the war. After Hong Kong fell into Japanese occupation, he returned to the Mainland and performed Cantonese operas to earn his keep. He came back to Hong Kong after the war and resumed his screen career. His two-part film series, Crime Doesn’t Pay (1949) broke box-office records and catapulted him to mega-stardom. His prominent works from this period include Black Heaven (1950), A Girl Named Leung Lang-yim (in two parts, 1950), Red and White Peonies (1952), etc. In 1952, Cheung co-founded The Union Film Enterprise Ltd with numerous film workers and took part in features such as Family (1953), Spring (1953), Autumn (1954), Father and Son (1954), Anna (1955), Romance at the Western Chamber (1956), A Beautiful Corpse Comes to Life (1956), Human Relationships (1959) and Long Live Money (1961). -

Download Heroic Grace: the Chinese Martial Arts Film Catalog (PDF)

UCLA Film and Television Archive Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office in San Francisco HEROIC GRACE: THE CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FILM February 28 - March 16, 2003 Los Angeles Front and inside cover: Lau Kar-fai (Gordon Liu Jiahui) in THE 36TH CHAMBER OF SHAOLIN (SHAOLIN SANSHILIU FANG ) present HEROIC GRACE: THE CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS FILM February 28 - March 16, 2003 Los Angeles Heroic Grace: The Chinese Martial Arts Film catalog (2003) is a publication of the UCLA Film and Television Archive, Los Angeles, USA. Editors: David Chute (Essay Section) Cheng-Sim Lim (Film Notes & Other Sections) Designer: Anne Coates Printed in Los Angeles by Foundation Press ii CONTENTS From the Presenter Tim Kittleson iv From the Presenting Sponsor Annie Tang v From the Chairman John Woo vi Acknowledgments vii Leaping into the Jiang Hu Cheng-Sim Lim 1 A Note on the Romanization of Chinese 3 ESSAYS Introduction David Chute 5 How to Watch a Martial Arts Movie David Bordwell 9 From Page to Screen: A Brief History of Wuxia Fiction Sam Ho 13 The Book, the Goddess and the Hero: Sexual Bérénice Reynaud 18 Aesthetics in the Chinese Martial Arts Film Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon—Passing Fad Stephen Teo 23 or Global Phenomenon? Selected Bibliography 27 FILM NOTES 31-49 PROGRAM INFORMATION Screening Schedule 51 Print & Tape Sources 52 UCLA Staff 53 iii FROM THE PRESENTER Heroic Grace: The Chinese Martial Arts Film ranks among the most ambitious programs mounted by the UCLA Film and Television Archive, taking five years to organize by our dedicated and intrepid Public Programming staff. -

Newsletter 63 More English Translation

Hong Kong Film Archive e-Newsletter 63 More English translation Publisher: Hong Kong Film Archive © 2013 Hong Kong Film Archive All rights reserved. No part of the content of this document may be reproduced, distributed or exhibited in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Research Golden Harvest and the Generational Change in 1970s Hong Kong Cinema Po Fung The 1970s were a period of pivotal transitions in Hong Kong cinema. It was also the era of Golden Harvest, from its birth to becoming the main pillar of the film industry. In changing times, Golden Harvest had the flexibility to move with the times, but on the other hand its success came from it spearheading much of the change. Looking at the changes in the company itself, one can see some of significant movements in Hong Kong cinema back then. A New Crop of Homegrown Directors Founded in 1970, Golden Harvest released its debut production The Invincible Eight in 1971. Before The Big Boss hit the screens on 31 October, 1971, Golden Harvest’s productions and distributions include Lo Wei’s The Invincible Eight; Zatoichi and the One-Armed Swordsman, co-directed by Hsu Tseng-hung and Yasuda Kimiyoshi; Hsu Tseng-hung’s The Last Duel, Yip Wing-cho’s The Blade Spares None; Huang Feng’s The Angry River and The Fast Sword; Lo Wei’s The Comet Strikes; Wong Tin-lam’s The Chase; Hsu Tseng-hung’s The Invincible Sword and Law Chi’s Thunderbolt.1 On genre, these were all martial arts, or wuxia films from the ‘new wuxia era’ trend driven by the Shaw Brothers. -

Martial Arts Cinema and Hong Kong Modernity

Martial Arts Cinema and Hong Kong Modernity Aesthetics, Representation, Circulation Man-Fung Yip Hong Kong University Press Th e University of Hong Kong Pokfulam Road Hong Kong www.hkupress.org © 2017 Hong Kong University Press ISBN 978-988-8390-71-7 (Hardback) All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any infor- mation storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. An earlier version of Chapter 2 “In the Realm of the Senses” was published as “In the Realm of the Senses: Sensory Realism, Speed, and Hong Kong Martial Arts Cinema,” Cinema Journal 53 (4): 76–97. Copyright © 2014 by the University of Texas Press. All rights reserved. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Printed and bound by Paramount Printing Co., Ltd. in Hong Kong, China Contents Acknowledgments viii Notes on Transliteration x Introduction: Martial Arts Cinema and Hong Kong Modernity 1 1. Body Semiotics 24 2. In the Realm of the Senses 56 3. Myth and Masculinity 85 4. Th e Diffi culty of Diff erence 115 5. Marginal Cinema, Minor Transnationalism 145 Epilogue 186 Filmography 197 Bibliography 203 Index 215 Introduction Martial Arts Cinema and Hong Kong Modernity Made at a time when confi dence was dwindling in Hong Kong due to a battered economy and in the aft ermath of the SARS epidemic outbreak,1 Kung Fu Hustle (Gongfu, 2004), the highly acclaimed action comedy by Stephen Chow, can be seen as an attempt to revitalize the positive energy and tenacious resolve—what is commonly referred to as the “Hong Kong spirit” (Xianggang jingshen)—that has allegedly pro- pelled the city’s amazing socioeconomic growth. -

University of Southampton Research Repository Eprints Soton

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Film Studies Hong Kong Cinema Since 1997: The Response of Filmmakers Following the Political Handover from Britain to the People’s Republic of China by Sherry Xiaorui Xu Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2012 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF HUMANITIES Film Studies Doctor of Philosophy HONG KONG CINEMA SINCE 1997: THE RESPONSE OF FILMMAKERS FOLLOWING THE POLITICAL HANDOVER FROM BRITAIN TO THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA by Sherry Xiaorui Xu This thesis was instigated through a consideration of the views held by many film scholars who predicted that the political handover that took place on the July 1 1997, whereby Hong Kong was returned to the sovereignty of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) from British colonial rule, would result in the “end” of Hong Kong cinema. -

A Different Brilliance—The D & B Story

1. Yes, Madam (1985): Michelle Yeoh 2. Love Unto Wastes (1986): (left) Elaine Jin; (right) Tony Leung Chiu-wai 3. An Autumn’s Tale (1987): (left) Chow Yun-fat; (right) Cherie Chung 4. Where’s Officer Tuba? (1986): Sammo Hung 5. Hong Kong 1941 (1984): (from left) Alex Man, Cecilia Yip, Chow Yun-fat 6. It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad World (1987): (front row from left) Loletta Lee, Elsie Chan, Pauline Kwan, Lydia Sum, Bill Tung; (back row) John Chiang 7. The Return of Pom Pom (1984): (left) John Sham; (right) Richard Ng 8. Heart to Hearts (1988): (from left) Dodo Cheng, George Lam, Vivian Chow Pic. 1-8 © 2010 Fortune Star Media Limited All Rights Reserved Contents 4 Foreword Kwok Ching-ling, Wong Ha-pak 〈Chapter I〉 Production • Cinema Circuits 10 D & B’s Development: From Production Company to Theatrical Distribution Po Fung Circuit 19 Retrospective on the Big Three: Dickson Poon and the Rise-and-Fall Story of the Wong Ha-pak D & B Cinema Circuit 29 An Unconventional Filmmaker—John Sham Eric Tsang Siu-wang 36 My Days at D & B Shu Kei In-Depth Portraits 46 John Sham Diversification Strategies of a Resolute Producer 54 Stephen Shin Targeting the Middle-Class Audience Demographic 61 Linda Kuk An Administrative Producer Who Embodies Both Strength and Gentleness 67 Norman Chan A Production Controller Who Changes the Game 73 Terence Chang Bringing Hong Kong Films to the International Stage 78 Otto Leong Cinema Circuit Management: Flexibility Is the Way to Go 〈Chapter II〉 Creative Minds 86 D & B: The Creative Trajectory of a Trailblazer Thomas Shin 92 From -

Japanese Women, Hong Kong Films, and Transcultural Fandom

SOME OF US ARE LOOKING AT THE STARS: JAPANESE WOMEN, HONG KONG FILMS, AND TRANSCULTURAL FANDOM Lori Hitchcock Morimoto Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Communication and Culture Indiana University April 2011 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Doctoral Committee _______________________________________ Prof. Barbara Klinger, Ph.D. _______________________________________ Prof. Gregory Waller, Ph.D. _______________________________________ Prof. Michael Curtin, Ph.D. _______________________________________ Prof. Michiko Suzuki, Ph.D. Date of Oral Examination: April 6, 2011 ii © 2011 Lori Hitchcock Morimoto ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii For Michael, who has had a long “year, two at the most.” iv Acknowledgements Writing is a solitary pursuit, but I have found that it takes a village to make a dissertation. I am indebted to my advisor, Barbara Klinger, for her insightful critique, infinite patience, and unflagging enthusiasm for this project. Gratitude goes to Michael Curtin, who saw promise in my early work and has continued to mentor me through several iterations of his own academic career. Gregory Waller’s interest in my research has been gratifying and encouraging, and I am most appreciative of Michiko Suzuki’s interest, guidance, and insights. Richard Bauman and Sumie Jones were enthusiastic readers of early work leading to this dissertation, and I am grateful for their comments and critique along the way. I would also like to thank Joan Hawkins for her enduring support during her tenure as Director of Graduate Studies in CMCL and beyond, as well as for the insights of her dissertation support group. -

The Cantonese "Youth Film” and Music of the 1960S in Hong Kong CHAN, Pui Shan a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment O

The Cantonese "Youth Film” and Music of the 1960s in Hong Kong CHAN, Pui Shan A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Music The Chinese University of Hong Kong January 2011 |f 23APR2fi>J !?I Thesis Committee Professor YU Siu Wah (Chair) Professor Michael Edward McCLELLAN (Thesis Supervisor) Professor Victor Amaro VICENTE (Committee Member) Professor LI Siu Leung (External Examiner) X i Contents Acknowledgements ii Abstract iii Chapter 1: 1 The Political and Social Influence on the Development of Hong Kong Film Industry and the Cantonese Cinema in the 1950s and the 1960s Chapter 2: 24 Defining the Genre: Three Characteristics of Hong Kong Cantonese Youth Film Chapter 3: 53 The Functions and Characteristics of Song in Cantonese Youth Film Chapter 4: 87 The Modernity of Cantonese Cinema and the City (Hong Kong) Conclusion: 104 Hong Kong Cantonese Youth Film and the Construction of Identity • Appendix 1 107 Appendix 2 109 Appendix 3 \\\ Bibliography 112 • ii Acknowledgements I am grateful for the teaching offered by the teaching staff and the sharing among friends at the Music Department of the Chinese University of Hong Kong. This experience is valuable to me. I have to thank Ada Chan, Lucy Choi, Angel Tsui, Julia Heung and Carman Tsang for their encouragement and prayers. I would also like to express my gratitude to my family which allowed me to pursue my studies in Music and Ethnomusicology. Furthermore, I cannot give enough thanks to my supervisor, Professor Michael E. McClellan for his patience, understanding, kindness, guidance, thoughtful and substantial support. -

The Transnational Asian Studio System: Cinema, Nation-State, and Globalization In

The Transnational Asian Studio System: Cinema, Nation-State, and Globalization in Cold War Asia by Sangjoon Lee A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Cinema Studies New York University May, 2011 _______________________ Zhang Zhen UMI Number: 3464660 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3464660 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346 ⓒ Sangjoon Lee All Right Reserved, 2011 DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my father, Lee Eui-choon, and my mother, Kim Sung-ki, for their love and support. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the generous support and encouragement of my committee members and fellow colleagues at NYU. My deepest debts are to my dissertation advisor; Professor Zhang Zhen has provided me through intellectual inspirations and guidance, a debt that can never be repaid. Professor Zhang is the best advisor anyone could ask for and her influence on me and this project cannot be measured. This dissertation owes the most to her. I have been extremely fortunate to have the support of another distinguished film scholar, Professor Yoshimoto Mitsuhiro, who has influenced my graduate studies since the first seminar I took at NYU. -

Wuxia Fictions: Chinese Martial Arts in Film, Literature and Beyond

EnterText 6.1 LEON HUNT Introduction For a genre that could be seen, not unreasonably, to be living on borrowed time, Chinese Martial Arts narratives have enjoyed a remarkable amount of critical attention and global visibility in recent years. It is hard to separate this phenomenon from the international impact of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (Ang Lee, China/US/Taiwan/Hong Kong, 2000) and the subsequent cycle of Pan-Chinese (and Pan-Asian) “Martial Arthouse” films that have followed it—Hero (Zhang Yimou, China/Hong Kong, 2002), House of Flying Daggers (Zhang Yimou, China/Hong Kong, 2004), The Promise (Chen Kaige, China/Hong Kong/Japan/South Korea, 2005), Seven Swords (Tsui Hark, Hong Kong/China/South Korea, 2005) and Huo Yuanjia/Fearless (Ronny Yu, Hong Kong/China, 2006). While this cycle might be located within what Dean Chan here calls a “fashionably nostalgic imaginary” in an East Asian context, in Western film criticism it popularised a previously unfamiliar generic label, the wuxia pian, which amongst other things served to differentiate the films from the more lowbrow “kung fu films” that met with considerable international success (if rather less critical recognition) in the 1970s. “Martial Arthouse” cinema was greeted by many Western critics as an apparently new trend in transnational action cinema, but as also indicative of a larger generic heritage that lent it cultural “authenticity.” This has often posed problems when, for example, reading the gender politics of wuxia heroines—is the “feminism” of Crouching Tiger evidence of the genre’s “Westernisation” or simply a more self-conscious elaboration on Leon Hunt: Introduction 1 EnterText 6.1 a tradition of women warriors that stretches back to the origins of the genre (and, indeed, its historical-mythical basis)? Significantly, the title of this issue is not “Kung Fu (or gongfu) Fictions,” the (Cantonese) term that entered Western discourse in the 1970s and acted as a catch-all label for the Chinese Martial Arts “craze” (including its pedagogic industries). -

Representations of Chinese Women Warriors in the Western Media

REPRESENTATIONS OF CHINESE WOMEN WARRIORS IN THE CINEMAS OF HONG KONG, MAINLAND CHINA AND TAIWAN SINCE 1980 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Chinese at the University of Canterbury by Yunxiang Chen University of Canterbury 2007 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENT .................................................................................. i ABSTRACT .................................................................................................... ii Introduction................................................................................................ 1 1. HERstory of Chinese women warriors ........................................... 13 1.1 Basic Imagery ...................................................................................... 13 1.2 Thematic Continuity.......................................................................... 17 1.3 A Brief History of Women Warriors in Chinese Cinemas....... .23 2. Western Influence .................................................................................. 43 2.1 Western Women Warriors ..............................................................44 2.2 Chinese Women Warriors in Hollywood ................................... 54 3. Hong Kong .................................................................................................61 3.1 Peking Opera Blue .................................................................................... 61 3.2 Dragon Inn .............................................................................................