Bachelor Thesis Arabic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Developing an Arabic Typography Course for Visual Communication Design

Developing an Arabic Typography course for Visual Communication Design Students in the Middle East and North African Region A thesis submitted to the School of Visual Communication Design, College of Communication and Information of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts by Basma Almusallam May, 2014 Thesis written by Basma Almusallam B.F.A, Kuwait University, 2008 M.F.A, Kent State University, 2014 Approved by ___________________________ Jillian Coorey, M.F.A., Advisor ___________________________ AnnMarie LeBlanc, M.F.A., Director, School of Visual Communication Design ___________________________ Stanley T. Wearden, Ph.D., Dean, College of Communication and Information Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS………………………………………………………………...... iii LIST OF FIGURES……………………………………………………………………….. v PREFACE………………………………………………………………………………..... vi CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………. 1 The Current Issue………………………………………………….. 1 Core Objectives……………………………………………………. 3 II. THE HISTORY OF THE ARABIC WRITING SYSTEM, CALLIGRAPHY AND TYPOGRAPHY………………………………………....………….. 4 The Arabic Writing System……………………………………….. 4 Arabic Calligraphy………………………………………………… 5 The Undocumented Art of Arabic Calligraphy……………….…… 6 The Shift Towards Typography and the Digital Era………………. 7 The Pressing Issue of the Present………………………………….. 8 A NOTE ON THE PROCESS…………………………………………………………….. 10 Applying a Framework for Research Documentation…………….. 11 Mental Model……………………………………………………… 12 Proposed User Testing……………………………………………. -

The Unique Ibn Al-Bawwab Manuscript

D.S.RICE THE UNIQUE IBN AL-BAWWAB MANUSCRIPT The text of the Qur'an was recorded'in the Prophet's lifetime, on a variety of writing materials.These inclu- ded such diverse materials as papyrus, parchment, leather, limestone slabs,shoulder blades,ribs, saddle- boards, &c. The Qur'an was first collectedunder the first caliph, Abu Bakr, and codified under the third caliph, 'Uthman. It was, in all likelihood, written on parchmenton both occasions,although one sourcehas it that papyrus was used on the first. All the early Qur'ans which have so far come to light are on parchment, with the exception of a small frag- ment on papyruswhich is attributed to the third Islamic century. The earliest Qur'ans w\ich have reachedus are written in variety of angular scripts commonly-but inappro- priately-describedas Kufic. No completeKufic Qur'an has, to my knowledge, survived and none is provided with a colophon. It is still a matter of controversy whether we possessany Qur'an which can be dated to the first century of the Muslim era.There are a number "signatures" of coclices which bear of the caliphs 'Uthman and 'Ali, but these have been shown to be later pious forgeries. Thanks to the studies published in the course of the last fifty years,especially by B. Moritz, J. von Karaba- cek, G. Bergstrásser,O. Pretzl,A. Grohmann, N. Abbott, and G. Levi della Vida much progresshas been made in the provisional dating of certain Kufic Qur'ans to the late first and to the second century of the Hijra. -

The Study of the Principles of Philosophy of Islamic Art Hasti Safavi University of Exeter Stocker Road, Exeter, United Kingdom, EX4 4PY

RUDN Journal of Philosophy 2020 Vol. 24 No. 1 23—38 Âåñòíèê ÐÓÄÍ. Ñåðèÿ: ÔÈËÎÑÎÔÈß http://journals.rudn.ru/philosophy DOI: 10.22363/2313-2302-2020-24-1-23-38 Research Article / Научная статья The Study of the Principles of Philosophy of Islamic Art Hasti Safavi University of Exeter Stocker Road, Exeter, United Kingdom, EX4 4PY Abstract. The main discourse on Islamic art in the western academia primarily views Islamic art through the lens of art history and sociology of art. Islamic art is considered as sacred in Islamic civilisation and culture, and derives its sanctity from the Quran as the fountain from which it has emanated, which Muslims consider to be the Word of God, much like Christ is the Word of God in Christianity. The Quran has played a formative role in shaping the trinity of sacred Islamic art which is Quranic recitation, calligraphy and architecture. However, another approach which not only is viable but can be considered of great importance to the study of Islamic art, is the employment and utilisation of principles of Islamic philosophy and Sufism which were the pillars of the intellectual milieu in which a given work of art is produced. The application of such principles allows a more comprehensive and detailed interpretation of a work of art. In this paper, the primary Islamic philosophy and sufi doctrines that will be dis- cussed are the concepts of imagination, colour, and calligraphy and examples of their applica- tion in the khānqāh and shrine ensemble of Shaykh Ṣafi al-Din Ardabīlī in Ardabil, Iran. Keywords: Islamic art, philosophy, Sufism, Quran, imagination, colour, calligraphy, Shaykh Ṣafi al-Din Ardabīlī’s shrine ensemble Article history: The article was submitted on 03.10.2019 The article was accepted on 06.11.2020 For citation: Hasti Safavi. -

Language Culture Type 2.Indd

Arabic script and typography is alphabetical; the direction of writing is from right to left; within a word, most letters form connected groups. AOne expects an alphabet to consist of a few dozen letters repre- senting one unique sound each. The Arabic alphabet evolved somewhat away from this ideal: although most letters correspond to a sound, a few letters are ambivalent between two or more sounds. Some letters don’t represent sound at all: they have only a grammatical function. For modern office use there are 28 basic letters, eight of them only differentiated from other letters by diacritics, and six optional letters for representing vowels. Older spellings made less use of diacritics for dif- ferentiating; on the other hand, to facilitate Qur’an recitation, additional vowel signs occur, along with elaborate cantillation marks. To acknowl- edge slight variations of the received text, some Qur’an editions have ad- ditional diacritics, discretely adding or eliminating consonant letters. As the Arabic script evolved into a connected script, it developed an elaborate system of assimilations and dissimilations between adjacent letters. Outside a small group of connoisseurs and calligraphers who study the principles established by the Ottoman letter artists, surpris- ingly little is understood of the efficiency and subtlety of this system,¹ and modern industrial type designs follow the approach found in el- ementary Western teaching materials.² There, beginners in Arabic script are given a maximally simplified scheme. While simplification is totally sound from a pedagogical perspective, it provides too narrow a basis for the development of professional typography. The Arabic script stems from the same source as the Latin, Greek, and Hebrew writing systems: Phoenician (figure 1).³ The underlying proto- alphabet had some two dozen characters; there were no vowels. -

Designing Software to Meet the Needs of International Users

DESIGNING SOFTWARE TO MEET THE NEEDS OF INTERNATIONAL USERS A Project Report Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Anthropology San José State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by David Mohr December 2013 © 2013 David Mohr ALL RIGHTS RESERVED SAN JOSÉ STATE UNIVERSITY The Undersigned Graduate Committee Approves the Project Report Titled DESIGNING SOFTWARE TO MEET THE NEEDS OF INTERNATIONAL USERS by David Mohr APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY _____________________________________________________________________________ Dr. Chuck Darrah, Department of Anthropology Date _____________________________________________________________________________ Dr. Roberto Gonzalez, Department of Anthropology Date _____________________________________________________________________________ Professor Awad Awad, Middle Eastern Studies, Department of Humanities, Date Arabic Coordinator, Department of World Languages and Literatures Abstract Most software applications are designed and built in North America, catering to English- speaking, North American users. Ethnography is commonly used to ensure the product addresses the needs of domestic customers, but there is no analogous research with regard to foreign consumers. As a result, often times the features in these applications fail to sufficiently address the needs, expectations, and workflow of non-English-speaking users. Although software engineering manuals minutely detail the technical aspects of bringing an English application to -

Qadi-S and the Political Use of the Mazalim Jurisdiction Under the ’Abbasids Mathieu Tillier

Qadi-s and the political use of the mazalim jurisdiction under the ’Abbasids Mathieu Tillier To cite this version: Mathieu Tillier. Qadi-s and the political use of the mazalim jurisdiction under the ’Abbasids. Christian Lange, Maribel Fierro. Public Violence in Islamic Societies: Power, Discipline, and the Construction of the Public Sphere, 7th–18th Centuries CE, Edinburgh University Press, pp.42-66, 2009. hal- 00587370v1 HAL Id: hal-00587370 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00587370v1 Submitted on 21 Apr 2011 (v1), last revised 8 Aug 2011 (v2) HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. GRAHAMS IMAC:Users:Graham:Public:GRAHAM'S IMAC JOBS:11654 - EUP - LANGE:EB0038 - LANGE TXT GRAHAMS IMAC:Users:Graham:Public:GRAHAM'S IMAC JOBS:11654 - EUP - LANGE:EB0038 - LANGE TXT 2 Qāḍīs and the political use of the maẓālim jurisdiction under the ʿAbbāsids Mathieu Tillier* The role of the maẓālim jurisdiction is generally regarded as threefold by present-day historians. As ordinary courts – all grievances could in theory be brought to the caliph – the maẓālim symbolized the discretion- ary authority vested in the ruler who could, at any time, exercise a power that he would ordinarily delegate to other judges. -

Studies and Sources in Islamic Art and Architecture

STUDIES AND SOURCES IN ISLAMIC ART AND ARCHITECTURE SUPPLEMENTS TO MUQARNAS Sponsored by the Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture at Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts. VOLUME IX PREFACING THE IMAGE THE WRITING OF ART HISTORY IN SIXTEENTH-CENTURY IRAN BY DAVID J. ROXBURGH BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON • KÖLN 2001 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Roxburgh, David J. Prefacing the image : the writing of art history in sixteenth-century Iran / David J. Roxburgh. p. cm. — (Studies and sources in Islamic art and architecture. Supplements to Muqarnas, ISSN 0921 0326 ; v. 9) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 9004113762 (alk. papier) 1. Art, Safavid—Historiography—Sources. 2. Art, Islamic—Iran– –Historiography—Sources. 3. Art criticism—Iran—History—Sources. I. Title. II. Series. N7283 .R69 2000 701’.18’095509024—dc21 00-062126 CIP Die Deutsche Bibliothek - CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Roxburgh, David J.: Prefacing the image : the writing of art history in sixteenth century Iran / by David J. Roxburgh. – Leiden; Boston; Köln : Brill, 2000 (Studies and sources in Islamic art and architectue; Vol 9) ISBN 90-04-11376-2 ISSN 0921-0326 ISBN 90 04 11376 2 © Copyright 2001 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910 Danvers MA 01923, USA. -

The Rehla of Ibn Battuta

Gackwad's Oriental Series Published under the Authority of the Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, Baroda General Editor : A. N. Jani, M.A.. Ph.D.. D.Litt., KavyaHrtha. Director. Oriental Institute No. 122 THE REHLA OF IBN BATTUTA ( INDIA. MALDIVE ISLANDS AND CEYLON ) ) ) THE REHLA OF IBN BATTCTA • •••••• (INDIA, MALDIVE ISLANDS AND CEYLON TRANSLATION AND COMMENTARY By Mabdi Husain, M.A. ( Punjab ), Ph.D. (London), D.Liu. ( Sorbcnne, Paris Oriental Institute Baroda 1976 First Woo: 1953 Stednd Edition (Reprint): 1976 Copies 500 Published with Financial Aid of the University Grants Commission, Govt, of Gujarat & M. S. University of Baroda Price Rs. 71=00 Copies can be had from : — The Manager, UNIVERSITY PUBLICATION SALES UNIT, M. S. University of Baroda ( Sadhana Press ), Near Palace Gate, Palace Road, BARODA-390 001 Re-printed by photo-offset process at 'the " Printrasee-' Bagikhana, Baroda. for Shri Rasiklal G. Patel, Manager, Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda Press (Sadhana Press), Near Palace Gate, Palace Road, Baroda and published on behalf of the Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda by Pr. h- N. Jani, Director, Oriental Institute, Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, Baroda, March 1976. FOREWORD The Rehla of Ibn Ea\\u\a was first published in the Gaekwad's Oriental Series as No. CXXII in 1953 by the then Director, the Late Professor G. H. Bhatt It should not be necessary to justify this reprint of an imported work of Muslim Cultural History, which has been in demand for a long time. I hope this reprint will fill a long-felt desideratum. T thanks the University Grants Commission, the Government of Gujarat and the M. -

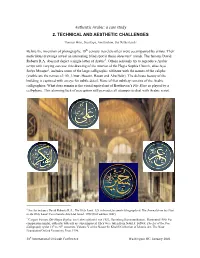

Authentic Arabic: a Case Study 2. TECHNICAL and AESTHETIC CHALLENGES

Authentic Arabic: a case study 2. TECHNICAL AND AESTHETIC CHALLENGES Thomas Milo, DecoType, Amsterdam, the Netherlands Before the invention of photography, 19th century travelers often were accompanied by artists. Their meticulous drawings reveal an interesting blind spot in these observers’ minds. The famous David Roberts R.A. does not depict a single letter of Arabic1. Others seriously try to reproduce Arabic script with varying success: this drawing of the interior of the Hagia Sophia Church, alias Aya Sofya Mosque2, includes some of the large calligraphic tableaux with the names of the caliphs (visible are the names of: Ali, Umar, Husain, Hasan and Abu Bakr). The delicate beauty of the building is captured with an eye for subtle detail. None of that subtlety remains of the Arabic calligraphies. What does remain is the visual equivalent of Beethoven’s Für Elise as played by a cell-phone. This alarming lack of perception still pervades all attempts to deal with Arabic script. 1 See for instance David Roberts R.A., The Holy Land, 123 coloured facsimile lithographs & The Journal from his Visit to the Holy Land, Terra Sancta Arts Ltd, Israel, 1982 (first edition 1842) 2 Caspare Fossati, Die Hagia Sophia, nach dem tafelwerk von 1852, Harenberg Kommunikation , Dortmund 1980. For comparison similar, authentic tableaux are superimposed. They were taken from Nabil F. Safwat, The Art of the Pen, Calligraphy of the 14th to 20th centuries, Volume V of the Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art, The Nour Foundation/Oxford University Press 1996. 20th International Unicode Conference Washington DC, January 2002 Authentic Arabic 2 – Technical and Æsthetic Challenges A more recent illustration is a drawing of the interior of the Süleymaniye Mosque in Istanbul3. -

Classifying Arabic Fonts Based on Design Characteristics: PANOSE-A

Classifying Arabic Fonts Based on Design Characteristics: PANOSE-A Jehan Janbi A Thesis In the Department of Computer Science & Software Engineering Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Computer Science) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada July 2016 © Jehan Janbi, 2016 Abstract In desktop publishing, fonts are essential components in each document design. With the development of font design software and tools, there are thousands of digital fonts. Increasing the number of available fonts makes selecting an appropriate font, which best serves the objective of a design, not an intuitive issue. Designers can search for a font like any other file types by using general information such as name and file format. But for document design purposes, the design features or visual characteristics of fonts are more meaningful for designers than font file information. Therefore, representing fonts’ design features by searchable and comparable data would facilitate searching and selecting a desirable font. One solution is to represent a font’s design features by a code composed of several digits. This solution has been implemented as a computerized system called PANOSE-1 for Latin script fonts. PANOSE-1 is a system for classifying and matching typefaces based on design features. It is composed of 10 digits, where each digit represents a specific design feature. It is used within several font management tools as an option for ordering and searching fonts based on their design features. It is also used in font replacement processes when an application or an operating system detects a missing font in an immigrant document or website. -

Multilingual Fonts for Arabic Script Jamil Khan* Department of Computer Science, University of Peshawar, Pakistan

chnology Te & n S o o ti ft a w a m r r Khan, J Inform Tech Softw Eng 2015, 5:3 e o f E Journal of n n I g f DOI: 10.4172/2165-7866.1000154 i o n l e a e n r r i n u g o J ISSN: 2165-7866 Information Technology & Software Engineering Research Article Open Access Multilingual Fonts for Arabic Script Jamil Khan* Department of Computer Science, University of Peshawar, Pakistan Abstract This paper is about developing a multi-lingual font for Pashto, Arabic, Urdu and Persian in such a way that the text for these four languages can be typed in it. Main purpose for developing fonts was to handle and remove many problems faced in earlier fonts. Fonts developed as a part of this work are ligature-based and text for all four languages (Pashto, Arabic, Urdu, and Persian) can be written in a single font. The paper is structured as follows: Shortcomings of existing fonts based on Arabic script and some text editors are discussed in Section-I. Section-II discusses the proposed solution to all those limitations. In Section-III, is about implementation of suggested solution, and Section-IV discusses features of the suggested solution. Section-V concludes the paper and Section-VI discusses future work discussed for Arabic typography. Keywords: Component; Formatting; Style; Styling; Insert manually in Inpage or sometimes with the help of other software such as CorelDraw. Introduction Liwal pashto system for windows During this work, some existing fonts based on Arabic script, including Pashto, Urdu, and Persian, are used in different bilingual text Liwal Pashto System–introduced in 2004 for Windows-98 and editors, and their limitations are pointed out. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The diwan of Abu Al-Hasan Al-Tihami Al-Furayh, Osman Saleh How to cite: Al-Furayh, Osman Saleh (1969) The diwan of Abu Al-Hasan Al-Tihami, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9931/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk THE DIWAN OF' ABU AL-HASAN AL-TIHAMI THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OP M.A. BY OSMA1I SALEH AL-PURAYH SCHOOL OP ORIENTAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OP DURHAM, U.K. JUNE 1969. (a) PREFACE There was an abundance of poets in the fourth and fifth centuries. Unfortunately, little is known of their work. There were many whose works were not published and I chose Abu-al- Hasan al-Tihami because I was impressed by his poems. The Alexandria copy, published in 1893 contains many grammatical and poetical mistakes.