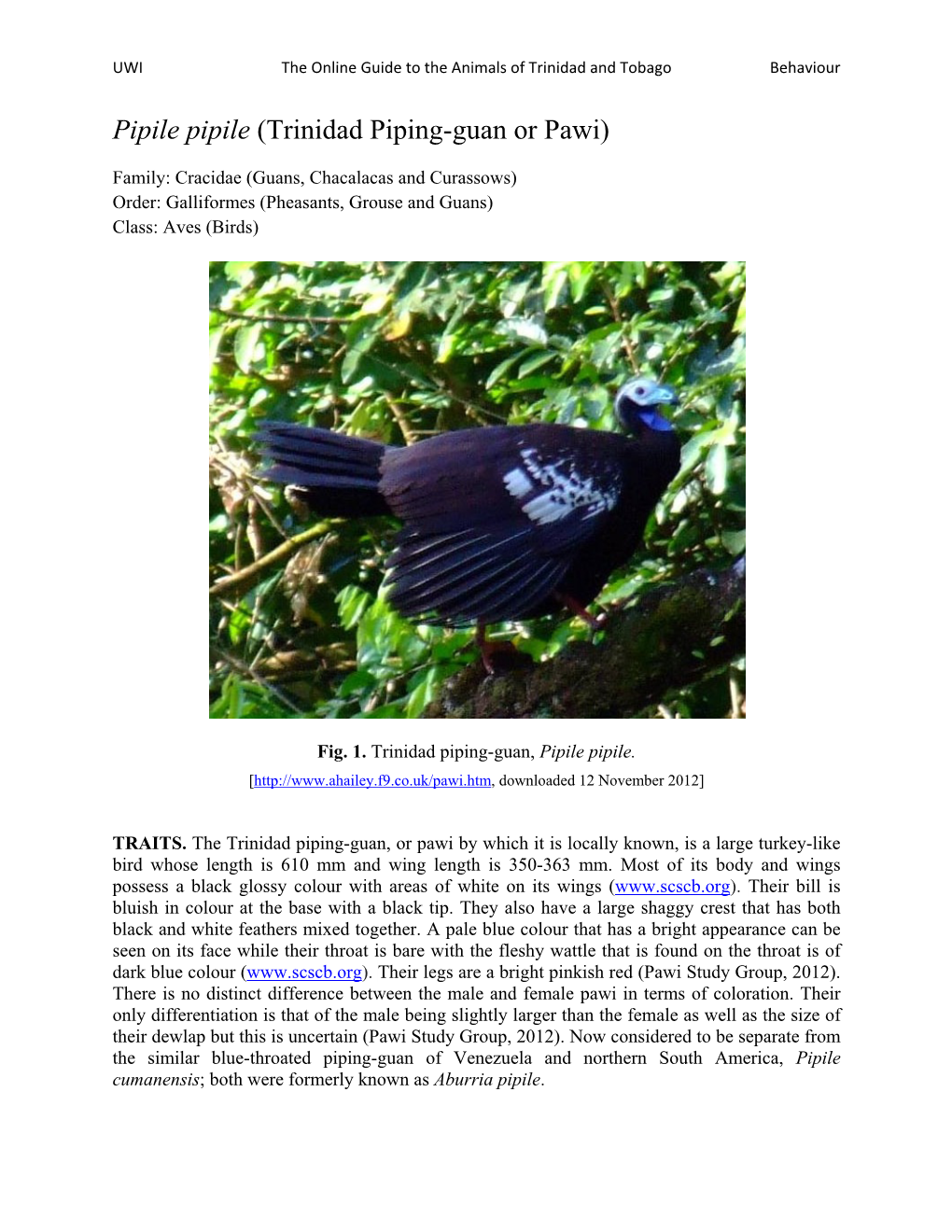

Pipile Pipile (Trinidad Piping-Guan Or Pawi)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Full Text in Pdf Format

Vol. 7: 77–84, 2009 ENDANGERED SPECIES RESEARCH Printed May 2009 doi: 10.3354/esr00184 Endang Species Res Published online May 5, 2009 OPENPEN ACCESSCCESS Status and conservation of the critically endangered Trinidad piping-guan Aburria pipile Floyd E. Hayes1, 4,*, Bryan Sanasie2, 5, Ishmaelangelo Samad3 1Department of Life Sciences, University of the West Indies, St. Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago 2Department of Biology, University of the Southern Caribbean, Maracas Valley, Trinidad and Tobago 3El Tucuche Hiking Lodge and Nature Retreat, Loango Village, Maracas, Trinidad and Tobago 4Present address: Department of Biology, Pacific Union College, 1 Angwin Avenue, Angwin, California 94508, USA 5Present address: 4867 Greenfield Drive Apt. 1, Berrien Springs, Michigan 49103, USA ABSTRACT: The Trinidad piping-guan Aburria pipile is endemic to the island of Trinidad, where it is critically endangered. We reviewed previously published historical records of the piping-guan and compiled reports from local residents and visiting birders. The piping-guan formerly occurred throughout much of Trinidad at all elevations, except perhaps along the west coast. Currently it is most abundant in the eastern half of the Northern Range, where considerable forest habitat remains, yet it remains rare and local. A few piping-guans may persist in forested areas of southern Trinidad, where the species was last reported in 2000. It may be extirpated in central Trinidad, where it was last reported in 1983. Hunting is clearly the major threat but appears to have declined in the past decade, at least in the Northern Range, due to recent public education campaigns. Recent sightings in areas where the piping-guan had previously not been reported for a century suggest a growing population in the Northern Range. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Mexico Chiapas 15Th April to 27Th April 2021 (13 Days)

Mexico Chiapas 15th April to 27th April 2021 (13 days) Horned Guan by Adam Riley Chiapas is the southernmost state of Mexico, located on the border of Guatemala. Our 13 day tour of Chiapas takes in the very best of the areas birding sites such as San Cristobal de las Casas, Comitan, the Sumidero Canyon, Isthmus of Tehuantepec, Tapachula and Volcan Tacana. A myriad of beautiful and sought after species includes the amazing Giant Wren, localized Nava’s Wren, dainty Pink-headed Warbler, Rufous-collared Thrush, Garnet-throated and Amethyst-throated Hummingbird, Rufous-browed Wren, Blue-and-white Mockingbird, Bearded Screech Owl, Slender Sheartail, Belted Flycatcher, Red-breasted Chat, Bar-winged Oriole, Lesser Ground Cuckoo, Lesser Roadrunner, Cabanis’s Wren, Mayan Antthrush, Orange-breasted and Rose-bellied Bunting, West Mexican Chachalaca, Citreoline Trogon, Yellow-eyed Junco, Unspotted Saw-whet Owl and Long- tailed Sabrewing. Without doubt, the tour highlight is liable to be the incredible Horned Guan. While searching for this incomparable species, we can expect to come across a host of other highlights such as Emerald-chinned, Wine-throated and Azure-crowned Hummingbird, Cabanis’s Tanager and at night the haunting Fulvous Owl! RBL Mexico – Chiapas Itinerary 2 THE TOUR AT A GLANCE… THE ITINERARY Day 1 Arrival in Tuxtla Gutierrez, transfer to San Cristobal del las Casas Day 2 San Cristobal to Comitan Day 3 Comitan to Tuxtla Gutierrez Days 4, 5 & 6 Sumidero Canyon and Eastern Sierra tropical forests Day 7 Arriaga to Mapastepec via the Isthmus of Tehuantepec Day 8 Mapastepec to Tapachula Day 9 Benito Juarez el Plan to Chiquihuites Day 10 Chiquihuites to Volcan Tacana high camp & Horned Guan Day 11 Volcan Tacana high camp to Union Juarez Day 12 Union Juarez to Tapachula Day 13 Final departures from Tapachula TOUR MAP… RBL Mexico – Chiapas Itinerary 3 THE TOUR IN DETAIL… Day 1: Arrival in Tuxtla Gutierrez, transfer to San Cristobal del las Casas. -

2011 , T Recovery

Strategy 2011 , t Recovery Species anjit and P.J.K. McGowan Pawi Edited by H. P. Nelson, C. Devenish, N. Bobb‐Prescot Alesha Naranjit, Kerrie Nar The Pawi Study Group, World Pheasant Association & Bird Life International CONTENTS 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 2.0 INTRODUCTION 4 3.0 SPECIES DESCRIPTION 4 3.1 The species’ functions and values 5 4.0 STATUS REVIEW 6 4.1 Historical account 6 4.2 Current distribution and demography 7 4.3 Habitat and resource assessment 8 4.4 Threat analysis 9 5.0 VISION AND GOALS 11 5.1 Vision 11 5.2 Goals 11 6.0 OBJECTIVES 12 6.1 Goal A: The Pawi lives throughout its natural habitat 12 6.2 Goal B: Greater involvement by Trinidadians in conservation of the species 13 7.0 ACTIONS 14 7.1 Goal A - Objective 1. To provide the necessary scientific knowledge 14 7.2 Goal A - Objective 2. To promote management that will increase Pawi numbers 15 7.3 Goal A - Objective 3. To review legislation on the Pawi and land-use planning 16 7.4 Goal B - Objective 1. Improve networking and co-ordination of stakeholders 16 7.5 Goal B - Objective 2. To increase awareness within the private sector 17 7.6 Goal B - Objective 3. Promote rural livelihoods that will meet local needs and not damage the survival prospects of the Pawi and its habitat. 18 7.7 Goal B - Objective 4. Conduct awareness-raising programmes 18 8.0 WORKS CITED 20 1 List of Acronyms CBO community based organization EMA Environmental Management Authority ESA Environmentally Sensitive Area ESS Environmentally Sensitive Species IUCN International Union for the Conservation of Nature NGO non-governmental organization PSG Pawi Study Group SPAW Specially Protected Areas and Wildlife Protocol of the Cartagena Convention UNDP United Nations Development Programme WPA World Pheasant Association 2 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Trinidad Piping-guan, Pipile pipile, known locally as Pawi, is endemic to Trinidad, having been elevated to full species by Strahl and Schmitz in 1997. -

Listing Five Foreign Bird Species in Colombia and Ecuador, South America, As Endangered Throughout Their Range; Final Rule

Vol. 78 Tuesday, No. 209 October 29, 2013 Part IV Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Part 17 Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Listing Five Foreign Bird Species in Colombia and Ecuador, South America, as Endangered Throughout Their Range; Final Rule VerDate Mar<15>2010 18:44 Oct 28, 2013 Jkt 232001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4717 Sfmt 4717 E:\FR\FM\29OCR4.SGM 29OCR4 mstockstill on DSK4VPTVN1PROD with RULES4 64692 Federal Register / Vol. 78, No. 209 / Tuesday, October 29, 2013 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR endangered or threatened we are proposed for these five foreign bird required to publish in the Federal species as endangered, following careful Fish and Wildlife Service Register a proposed rule to list the consideration of all comments we species and, within 1 year of received during the public comment 50 CFR Part 17 publication of the proposed rule, a final periods. rule to add the species to the Lists of [Docket No. FWS–R9–IA–2009–12; III. Costs and Benefits 4500030115] Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants. On July 7, 2009, we We have not analyzed the costs or RIN 1018–AV75 published a proposed rule in which we benefits of this rulemaking action determined that the blue-billed because the Act precludes consideration Endangered and Threatened Wildlife curassow, brown-banded antpitta, Cauca of such impacts on listing and delisting and Plants; Listing Five Foreign Bird guan, gorgeted wood-quail, and determinations. Instead, listing and Species in Colombia and Ecuador, Esmeraldas woodstar currently face delisting decisions are based solely on South America, as Endangered numerous threats and warrant listing the best scientific and commercial Throughout Their Range under the Act as endangered species (74 information available regarding the AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, FR 32308). -

TAS Trinidad and Tobago Birding Tour June 14-24, 2012 Brian Rapoza, Tour Leader

TAS Trinidad and Tobago Birding Tour June 14-24, 2012 Brian Rapoza, Tour Leader This past June 14-24, a group of nine birders and photographers (TAS President Joe Barros, along with Kathy Burkhart, Ann Wiley, Barbara and Ted Center, Nancy and Bruce Moreland and Lori and Tony Pasko) joined me for Tropical Audubon’s birding tour to Trinidad and Tobago. We were also joined by Mark Lopez, a turtle-monitoring colleague of Ann’s, for the first four days of the tour. The islands, which I first visited in 2008, are located between Venezuela and Grenada, at the southern end of the Lesser Antilles, and are home to a distinctly South American avifauna, with over 470 species recorded. The avifauna is sometimes referred to as a Whitman’s sampler of tropical birding, in that most neotropical bird families are represented on the islands by at least one species, but never by an overwhelming number, making for an ideal introduction for birders with limited experience in the tropics. The bird list includes two endemics, the critically endangered Trinidad Piping Guan and the beautiful yet considerably more common Trinidad Motmot; we would see both during our tour. Upon our arrival in Port of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago’s capital, we were met by the father and son team of Roodal and Dave Ramlal, our drivers and bird guides during our stay in Trinidad. Ruddy Ground-Dove, Gray- breasted Martin, White-winged Swallow and Carib Grackle were among the first birds encountered around the airport. We were immediately driven to Asa Wright Nature Centre, in the Arima Valley of Trinidad’s Northern Range, our base of operations for the first seven nights of our tour. -

RESTRICTED ANIMAL LIST (Part A) §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME

RESTRICTED ANIMAL LIST (Part A) §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME §4-71-6.5 LIST OF RESTRICTED ANIMALS September 25, 2018 PART A: FOR RESEARCH AND EXHIBITION SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME INVERTEBRATES PHYLUM Annelida CLASS Hirudinea ORDER Gnathobdellida FAMILY Hirudinidae Hirudo medicinalis leech, medicinal ORDER Rhynchobdellae FAMILY Glossiphoniidae Helobdella triserialis leech, small snail CLASS Oligochaeta ORDER Haplotaxida FAMILY Euchytraeidae Enchytraeidae (all species in worm, white family) FAMILY Eudrilidae Helodrilus foetidus earthworm FAMILY Lumbricidae Lumbricus terrestris earthworm Allophora (all species in genus) earthworm CLASS Polychaeta ORDER Phyllodocida 1 RESTRICTED ANIMAL LIST (Part A) §4-71-6.5 SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME FAMILY Nereidae Nereis japonica lugworm PHYLUM Arthropoda CLASS Arachnida ORDER Acari FAMILY Phytoseiidae Iphiseius degenerans predator, spider mite Mesoseiulus longipes predator, spider mite Mesoseiulus macropilis predator, spider mite Neoseiulus californicus predator, spider mite Neoseiulus longispinosus predator, spider mite Typhlodromus occidentalis mite, western predatory FAMILY Tetranychidae Tetranychus lintearius biocontrol agent, gorse CLASS Crustacea ORDER Amphipoda FAMILY Hyalidae Parhyale hawaiensis amphipod, marine ORDER Anomura FAMILY Porcellanidae Petrolisthes cabrolloi crab, porcelain Petrolisthes cinctipes crab, porcelain Petrolisthes elongatus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes eriomerus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes gracilis crab, porcelain Petrolisthes granulosus crab, porcelain Petrolisthes -

Journal of the Trinidad and Tobago Field Naturalists' Club

Journal of the Trinidad and Tobago Field Naturalists' Club Natura Maxime Miranda in Minimis Published July 1986. LIVING WORLD is published biennially by the Trinidad and Tobago Field Naturalists' Club. This issue is dedicated to Rtchard ffrench. All rights reserved. Type·setting, design and page mechanicals by 8M Publica· tions, 20 Collens Road, Maraval, Trinidad. Dedication RICHARD FFRENCH was born in England and shortly after gra duating from Oxford University came to the West Indies with his wife Margaret. He lived in Barbados for three years and then came to Trinidad to teach at St Peter's School, Pointe-a'-Pierre. His interest in birds was alreadY well developed bu t so was his interest in music and he contributed much to the cultural life of Trinidad and Tobago in both of these fields. He is a past president of the Trinidad and Tobago Field Naturalists' Club and edited its jour nal for a number of years. He was also chairman of the Board of Management of the Asa Wright Nature Centre for some years and served as a member of the board after his term as chairman. From his arrival in Trinidad to his departure in April 1985 he studied the avifauna of our two islands and produced his Guide to the Birds of Trinidad and Tobago in 1973. It is now in its fourth edition. A smaller (and cheaper) guide to the common birds has just been published and shDuld introduce the study of birds to an even wider pUblic. He has published several papers in this journal and in others and with Peter Bacon wrote Nature Trails of Trinidad. -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

SWFSC Archive

CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................................ ii LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................... ii INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................... 1 OBJECTIVES ............................................................................................................................... 1 STUDY AREA AND ITINERARY ............................................................................................. 2 MATERIALS AND METHODS ................................................................................................. 3 Oceanography ............................................................................................................................. 3 Net Tows ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Acoustic Backscatter.................................................................................................................... 4 Seabirds ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Contour Plots............................................................................................................................... 5 RESULTS ..................................................................................................................................... -

Endangered Species (Import and Export) Act (Chapter 92A)

1 S 23/2005 First published in the Government Gazette, Electronic Edition, on 11th January 2005 at 5:00 pm. NO.S 23 ENDANGERED SPECIES (IMPORT AND EXPORT) ACT (CHAPTER 92A) ENDANGERED SPECIES (IMPORT AND EXPORT) ACT (AMENDMENT OF FIRST, SECOND AND THIRD SCHEDULES) NOTIFICATION 2005 In exercise of the powers conferred by section 23 of the Endangered Species (Import and Export) Act, the Minister for National Development hereby makes the following Notification: Citation and commencement 1. This Notification may be cited as the Endangered Species (Import and Export) Act (Amendment of First, Second and Third Schedules) Notification 2005 and shall come into operation on 12th January 2005. Deletion and substitution of First, Second and Third Schedules 2. The First, Second and Third Schedules to the Endangered Species (Import and Export) Act are deleted and the following Schedules substituted therefor: ‘‘FIRST SCHEDULE S 23/2005 Section 2 (1) SCHEDULED ANIMALS PART I SPECIES LISTED IN APPENDIX I AND II OF CITES In this Schedule, species of an order, family, sub-family or genus means all the species of that order, family, sub-family or genus. First column Second column Third column Common name for information only CHORDATA MAMMALIA MONOTREMATA 2 Tachyglossidae Zaglossus spp. New Guinea Long-nosed Spiny Anteaters DASYUROMORPHIA Dasyuridae Sminthopsis longicaudata Long-tailed Dunnart or Long-tailed Sminthopsis Sminthopsis psammophila Sandhill Dunnart or Sandhill Sminthopsis Thylacinidae Thylacinus cynocephalus Thylacine or Tasmanian Wolf PERAMELEMORPHIA -

Recovery of the Trinidad Piping-Guan ( Pipile Pipile )

Expedition ID: 300605 Grant Category : Gold Grant Amount: $14,500 Project Pawi: Recovery of the Trinidad Piping-Guan ( Pipile pipile ) Team members: Jahson Alemu, Emma Davis, Aidan Keane, Kevin Mahabir, Srishti Mohais, Alesha Naranjit, Kerrie Naranjit, Bethany Stoker Contact: Aidan Keane Imperial College London Silwood Park Buckhurst Road Ascot Berks SL5 7PY [email protected] Acknowledgements The team would like to thank British Petroleum (BP), BirdLife International, Fauna and Flora International (FFI), Conservation International, Wildlife Conservation Society for funding the project. Special thanks go to Phil McGowan at the World Pheasant Association and to Marianne, Robyn and Kate at the BP Conservation Programme whose help and patience have been invaluable throughout. Project Pawi was only possible because of the generosity, support and encouragement of a large number of people within Trinidad itself, to whom we are very grateful. The team would particularly like to thank the members of the Pawi Study Group, tirelessly led by John and Margaret Cooper, for their practical help, thoughtful discussions and friendship. On ecological matters the guidance and expertise of Adrian Hailey and Howard Nelson was greatly appreciated. Grande Riviere has been at the heart of efforts to study the Pawi for many years, and once again played a central role in our project. We are indebted to owners of the Grande Riviere house for their generosity in allowing us to use the site as our base. The team would especially like to thank the guides of the Grande Riviere Nature Tour Guide Association and Mr Guy for their help and friendship. We are very grateful for the practical support provided by the University of the West Indies, Asa Wright, the Forestry Department, the Wildlife Section and the National Parks Section.