Journal of the Trinidad and Tobago Field Naturalists' Club

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Argentina New Birding ‘Lodges’ in Argentina James Lowen

>> BIRDING SITES NEW BIRDING LoDGES IN ARGENTINA New birding ‘lodges’ in Argentina James Lowen Birders visiting Argentina tend to stay in hotels near but not at birding sites because the country lacks lodges of the type found elsewhere in the Neotropics. However, a few new establishments are bucking the trend and may deserve to be added to country’s traditional birding route. This article focuses on two of them and highlights a further six. Note: all photographs were taken at the sites featured in the article. Long-trained Nightjar Macropsalis forcipata, Posada Puerto Bemberg, Misiones, June 2009 (emilio White); there is a good stakeout near the posada neotropical birding 6 49 >> BIRDING SITES NEW BIRDING LoDGES IN ARGENTINA lthough a relatively frequent destination Posada Puerto Bemberg, for Neotropical birders, Argentina—unlike A most Neotropical countries—has relatively Misiones few sites such as lodges where visitors can Pretty much every tourist visiting Misiones bird and sleep in the same place. Fortunately, province in extreme north-east Argentina makes there are signs that this is changing, as estancia a beeline for Iguazú Falls, a leading candidate to owners build lodgings and offer ecotourism- become one of UNESCO’s ‘seven natural wonders related services. In this article, I give an of the world’. Birders are no different, but also overview of two such sites that are not currently spend time in the surrounding Atlantic Forest on the standard Argentine birding trail—but of the Parque Nacional de Iguazú. Although should be. Both offer good birding and stylish some birders stay in the national park’s sole accommodation in a beautiful setting, which may hotel, most day-trip the area from hotels in interest those with non-birding partners. -

Lista Roja De Las Aves Del Uruguay 1

Lista Roja de las Aves del Uruguay 1 Lista Roja de las Aves del Uruguay Una evaluación del estado de conservación de la avifauna nacional con base en los criterios de la Unión Internacional para la Conservación de la Naturaleza. Adrián B. Azpiroz, Laboratorio de Genética de la Conservación, Instituto de Investigaciones Biológicas Clemente Estable, Av. Italia 3318 (CP 11600), Montevideo ([email protected]). Matilde Alfaro, Asociación Averaves & Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de la República, Iguá 4225 (CP 11400), Montevideo ([email protected]). Sebastián Jiménez, Proyecto Albatros y Petreles-Uruguay, Centro de Investigación y Conservación Marina (CICMAR), Avenida Giannattasio Km 30.5. (CP 15008) Canelones, Uruguay; Laboratorio de Recursos Pelágicos, Dirección Nacional de Recursos Acuáticos, Constituyente 1497 (CP 11200), Montevideo ([email protected]). Cita sugerida: Azpiroz, A.B., M. Alfaro y S. Jiménez. 2012. Lista Roja de las Aves del Uruguay. Una evaluación del estado de conservación de la avifauna nacional con base en los criterios de la Unión Internacional para la Conservación de la Naturaleza. Dirección Nacional de Medio Ambiente, Montevideo. Descargo de responsabilidad El contenido de esta publicación es responsabilidad de los autores y no refleja necesariamente las opiniones o políticas de la DINAMA ni de las organizaciones auspiciantes y no comprometen a estas instituciones. Las denominaciones empleadas y la forma en que aparecen los datos no implica de parte de DINAMA, ni de las organizaciones auspiciantes o de los autores, juicio alguno sobre la condición jurídica de países, territorios, ciudades, personas, organizaciones, zonas o de sus autoridades, ni sobre la delimitación de sus fronteras o límites. -

Recolecta De Artrópodos Para Prospección De La Biodiversidad En El Área De Conservación Guanacaste, Costa Rica

Rev. Biol. Trop. 52(1): 119-132, 2004 www.ucr.ac.cr www.ots.ac.cr www.ots.duke.edu Recolecta de artrópodos para prospección de la biodiversidad en el Área de Conservación Guanacaste, Costa Rica Vanessa Nielsen 1,2, Priscilla Hurtado1, Daniel H. Janzen3, Giselle Tamayo1 & Ana Sittenfeld1,4 1 Instituto Nacional de Biodiversidad (INBio), Santo Domingo de Heredia, Costa Rica. 2 Dirección actual: Escuela de Biología, Universidad de Costa Rica, 2060 San José, Costa Rica. 3 Department of Biology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, USA. 4 Dirección actual: Centro de Investigación en Biología Celular y Molecular, Universidad de Costa Rica. [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Recibido 21-I-2003. Corregido 19-I-2004. Aceptado 04-II-2004. Abstract: This study describes the results and collection practices for obtaining arthropod samples to be stud- ied as potential sources of new medicines in a bioprospecting effort. From 1994 to 1998, 1800 arthropod sam- ples of 6-10 g were collected in 21 sites of the Área de Conservación Guancaste (A.C.G) in Northwestern Costa Rica. The samples corresponded to 642 species distributed in 21 orders and 95 families. Most of the collections were obtained in the rainy season and in the tropical rainforest and dry forest of the ACG. Samples were obtained from a diversity of arthropod orders: 49.72% of the samples collected corresponded to Lepidoptera, 15.75% to Coleoptera, 13.33% to Hymenoptera, 11.43% to Orthoptera, 6.75% to Hemiptera, 3.20% to Homoptera and 7.89% to other groups. -

REGUA Bird List July 2020.Xlsx

Birds of REGUA/Aves da REGUA Updated July 2020. The taxonomy and nomenclature follows the Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Annotated checklist of the birds of Brazil by the Brazilian Ornithological Records Committee, updated June 2015 - based on the checklist of the South American Classification Committee (SACC). Atualizado julho de 2020. A taxonomia e nomenclatura seguem o Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos (CBRO), Lista anotada das aves do Brasil pelo Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos, atualizada em junho de 2015 - fundamentada na lista do Comitê de Classificação da América do Sul (SACC). -

INSECTA: LEPIDOPTERA) DE GUATEMALA CON UNA RESEÑA HISTÓRICA Towards a Synthesis of the Papilionoidea (Insecta: Lepidoptera) from Guatemala with a Historical Sketch

ZOOLOGÍA-TAXONOMÍA www.unal.edu.co/icn/publicaciones/caldasia.htm Caldasia 31(2):407-440. 2009 HACIA UNA SÍNTESIS DE LOS PAPILIONOIDEA (INSECTA: LEPIDOPTERA) DE GUATEMALA CON UNA RESEÑA HISTÓRICA Towards a synthesis of the Papilionoidea (Insecta: Lepidoptera) from Guatemala with a historical sketch JOSÉ LUIS SALINAS-GUTIÉRREZ El Colegio de la Frontera Sur (ECOSUR). Unidad Chetumal. Av. Centenario km. 5.5, A. P. 424, C. P. 77900. Chetumal, Quintana Roo, México, México. [email protected] CLAUDIO MÉNDEZ Escuela de Biología, Universidad de San Carlos, Ciudad Universitaria, Campus Central USAC, Zona 12. Guatemala, Guatemala. [email protected] MERCEDES BARRIOS Centro de Estudios Conservacionistas (CECON), Universidad de San Carlos, Avenida La Reforma 0-53, Zona 10, Guatemala, Guatemala. [email protected] CARMEN POZO El Colegio de la Frontera Sur (ECOSUR). Unidad Chetumal. Av. Centenario km. 5.5, A. P. 424, C. P. 77900. Chetumal, Quintana Roo, México, México. [email protected] JORGE LLORENTE-BOUSQUETS Museo de Zoología, Facultad de Ciencias, UNAM. Apartado Postal 70-399, México D.F. 04510; México. [email protected]. Autor responsable. RESUMEN La riqueza biológica de Mesoamérica es enorme. Dentro de esta gran área geográfi ca se encuentran algunos de los ecosistemas más diversos del planeta (selvas tropicales), así como varios de los principales centros de endemismo en el mundo (bosques nublados). Países como Guatemala, en esta gran área biogeográfi ca, tiene grandes zonas de bosque húmedo tropical y bosque mesófi lo, por esta razón es muy importante para analizar la diversidad en la región. Lamentablemente, la fauna de mariposas de Guatemala es poco conocida y por lo tanto, es necesario llevar a cabo un estudio y análisis de la composición y la diversidad de las mariposas (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea) en Guatemala. -

ON 24(1) 35-53.Pdf

ORNITOLOGIA NEOTROPICAL 24: 35–53, 2013 © The Neotropical Ornithological Society CONTRIBUTION OF DIFFERENT FOREST TYPES TO THE BIRD COMMUNITY OF A SAVANNA LANDSCAPE IN COLOMBIA Natalia Ocampo-Peñuela1,2 & Andrés Etter1 1Departamento de Ecología y Territorio, Facultad de Estudios Ambientales y Rurales - Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá DC, Colombia. E-mail: [email protected] 2Nicholas School of the Environment, Box 90328, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708, USA. Resumen. – Contribución de diferentes tipos de bosque a la comunidad de aves en un paisaje de sabana en Colombia. – La heterogeneidad del paisaje es particularmente importante en paisajes frag- mentados, donde cada fragmento contribuye a la biodiversidad del paisaje. Este aspecto ha sido menos estudiado en paisajes naturalmente fragmentados, comparado con aquellos fragmentados por activ- idades antrópicas. Estudiamos las sabanas de la región de la Orinoquia en Colombia, un paisaje natural- mente fragmentado. El objetivo fue determinar la contribución de tres tipos de bosque de un mosaico de bosque-sabana (bosque de altillanura, bosques riparios anchos, bosques riparios angostos), a la avi- fauna del paisaje. Nos enfocamos en la estructura de la comunidad de aves, analizando la riqueza de especies y la composición de los gremios tróficos, las asociaciones de hábitat, y la movilidad relativa de las especies. Usando observaciones, grabaciones, y capturas con redes de niebla, registramos 109 especies. Los tres tipos del paisaje mostraron diferencias importantes, y complementariedad con respecto a la composición de las aves. Los análisis de gremios tróficos, movilidad, y asolación de hábitat reforzaron las diferencias entre los tipos de bosque. El bosque de altillanura presentó la mayor riqueza de aves, y a la vez también la mayor cantidad de especies únicas. -

Butterflies (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea) in a Coastal Plain Area in the State of Paraná, Brazil

62 TROP. LEPID. RES., 26(2): 62-67, 2016 LEVISKI ET AL.: Butterflies in Paraná Butterflies (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea) in a coastal plain area in the state of Paraná, Brazil Gabriela Lourenço Leviski¹*, Luziany Queiroz-Santos¹, Ricardo Russo Siewert¹, Lucy Mila Garcia Salik¹, Mirna Martins Casagrande¹ and Olaf Hermann Hendrik Mielke¹ ¹ Laboratório de Estudos de Lepidoptera Neotropical, Departamento de Zoologia, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Caixa Postal 19.020, 81.531-980, Curitiba, Paraná, Brazil Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected]٭ Abstract: The coastal plain environments of southern Brazil are neglected and poorly represented in Conservation Units. In view of the importance of sampling these areas, the present study conducted the first butterfly inventory of a coastal area in the state of Paraná. Samples were taken in the Floresta Estadual do Palmito, from February 2014 through January 2015, using insect nets and traps for fruit-feeding butterfly species. A total of 200 species were recorded, in the families Hesperiidae (77), Nymphalidae (73), Riodinidae (20), Lycaenidae (19), Pieridae (7) and Papilionidae (4). Particularly notable records included the rare and vulnerable Pseudotinea hemis (Schaus, 1927), representing the lowest elevation record for this species, and Temenis huebneri korallion Fruhstorfer, 1912, a new record for Paraná. These results reinforce the need to direct sampling efforts to poorly inventoried areas, to increase knowledge of the distribution and occurrence patterns of butterflies in Brazil. Key words: Atlantic Forest, Biodiversity, conservation, inventory, species richness. INTRODUCTION the importance of inventories to knowledge of the fauna and its conservation, the present study inventoried the species of Faunal inventories are important for providing knowledge butterflies of the Floresta Estadual do Palmito. -

The Influence of Agriculture on Avian Communities Near Villavicencio

GENERAL NOTES 381 By day 35 foot span already averaged 99% of adult size. Rapid attainment of adult foot size likely reflects the importance of the many tasks the foot performs (e.g., perching, climb- ing, feeding). At hatching, bill width was already 49.4% of adult size, although, at day 35, bill width was closer to adult size than length or depth. This was the result of a more rapid development in width before hatching, since the growth rates of all bill dimensions were about the same throughout nestling development. Since bill width was measured at the base of the bill, it is about equivalent to gape width. The rapid increase of gape width in other species (Dunn, Condor 77:431-438, 1975; Holcomb, Nebraska Bird Rev. 36:2232, 1968; Holcomb and Twiest, Ohio J. Sci. 68:277-284, 1968; Royama, Ibis 108:313347, 1966) has been interpreted (OConnor,’ Ibis 119:147-166, 1975) as important in increasing parental feeding efficiency because it allows the young to consume larger food items. Young Monk Parakeets are fed by regurgitation. This material was described as a white, milky fluid (Alexandra 1977). Ac- cordingly, the ability to consume large food items may be of little value to nestlings. Since food is provided by the parents in a rather processed form, there would be little advantage in rapid bill growth for the purpose of processing food items. Fledglings, too, are fed by regurgitation, although they soon begin to do some foraging for themselves. Yet, as Portmann (Proc. 11th Int. Omithol. Congr. 138-151, 1955) has shown, as the brain develops early, the skull must develop similarly to accommodate it. -

Bird Monitoring Study Data Report Jan 2013 – Dec 2016

Bird Monitoring Study Data Report Jan 2013 – Dec 2016 Jennifer Powell Cloudbridge Nature Reserve October 2017 Photos: Nathan Marcy Common Chlorospingus Slate-throated Redstart (Chlorospingus flavopectus) (Myioborus miniatus) CONTENTS Contents ............................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Tables .................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Figures................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 1 Project Background ................................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Project Goals ................................................................................................................................................... 7 2 Locations ..................................................................................................................................................................... 8 2.1 Current locations ............................................................................................................................................. 8 2.3 Historic locations ..........................................................................................................................................10 -

Bird) Species List

Aves (Bird) Species List Higher Classification1 Kingdom: Animalia, Phyllum: Chordata, Class: Reptilia, Diapsida, Archosauria, Aves Order (O:) and Family (F:) English Name2 Scientific Name3 O: Tinamiformes (Tinamous) F: Tinamidae (Tinamous) Great Tinamou Tinamus major Highland Tinamou Nothocercus bonapartei O: Galliformes (Turkeys, Pheasants & Quail) F: Cracidae Black Guan Chamaepetes unicolor (Chachalacas, Guans & Curassows) Gray-headed Chachalaca Ortalis cinereiceps F: Odontophoridae (New World Quail) Black-breasted Wood-quail Odontophorus leucolaemus Buffy-crowned Wood-Partridge Dendrortyx leucophrys Marbled Wood-Quail Odontophorus gujanensis Spotted Wood-Quail Odontophorus guttatus O: Suliformes (Cormorants) F: Fregatidae (Frigatebirds) Magnificent Frigatebird Fregata magnificens O: Pelecaniformes (Pelicans, Tropicbirds & Allies) F: Ardeidae (Herons, Egrets & Bitterns) Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis O: Charadriiformes (Sandpipers & Allies) F: Scolopacidae (Sandpipers) Spotted Sandpiper Actitis macularius O: Gruiformes (Cranes & Allies) F: Rallidae (Rails) Gray-Cowled Wood-Rail Aramides cajaneus O: Accipitriformes (Diurnal Birds of Prey) F: Cathartidae (Vultures & Condors) Black Vulture Coragyps atratus Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura F: Pandionidae (Osprey) Osprey Pandion haliaetus F: Accipitridae (Hawks, Eagles & Kites) Barred Hawk Morphnarchus princeps Broad-winged Hawk Buteo platypterus Double-toothed Kite Harpagus bidentatus Gray-headed Kite Leptodon cayanensis Northern Harrier Circus cyaneus Ornate Hawk-Eagle Spizaetus ornatus Red-tailed -

Rufous-Faced Crake Laterallus Xenopterus

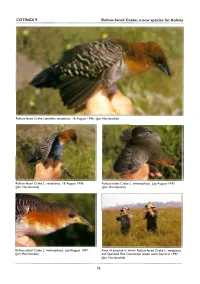

COTINGA 9 Rufous-faced Crake: a new species for Bolivia Rufous-faced Crake Laterallus xenopterus. 18 August 1996. (Jon Hornbuckle) Rufous-faced Crake L. xenopterus. 18 August 1996. Rufous-sided Crake L. melanophaius. July/August 1997. (Jon Hornbuckle) (Jon Hornbuckle) Rufous-sided Crake L. melanophaius. July/August 1997. Area of savanna in which Rufous-faced Crake L. xenopterus (Jon Hornbuckle) and Speckled Rail Coturnicops notata were found in 1997. (Jon Hornbuckle) 7 6 COTINGA 9 Rufous-faced Crake Laterallus xenopterus: a new species for Bolivia, with notes on its identification, distribution, ecology and conservation Robin Brace, Jon Hornbuckle and Paul St Pierre Se describen los primeros registros de Laterallus xenopterus para Bolivia, en base a un individuo capturado el 18 agosto 1996 y tres observaciones obtenidas durante agosto 1997, todas en la Estación Biológica del Beni (EBB) (dpto. Beni). Anteriormente a nuestras observaciones, la distribución conocida de esta especie, considerada amenazada7, se extendía por sólo unos pocos sitios en Paraguay y un área del Brasil. Las aves fueron localizadas en la sabana semi-inundada caracterizada por la vegetación continua separada por angostos canales, los que claramente facilitan los desplazamientos a nivel del suelo. Si bien el registro de 1996 muestra que L. xenopterus puede vivir junto a L. melanophaius, nuestras observaciones en 1997 indican, concordando con informaciones anteriores, que L. xenopterus parece evitar áreas cubiertas por m ás que unos pocos centímetros de agua. Se resumen los detalles de identificación, enfatizando las diferencias con L. melanophaius. De particular im portancia son (i) el notable barrado blanco y negro en las cobertoras alares, terciarias y escapulares; (ii) la extensión del color rufo de la cabeza sobre la nuca y la espalda, y (iii) el pico corto y relativamente profundo, en parte de color gris-turquesa. -

Peru Conservation Recorded Wildlife at Taricaya

Peru Conservation Recorded Wildlife at Taricaya Butterflies (Mariposas) in Taricaya Reserve, Madre de Dios CLASS: Insecta ORDER: Lepidoptera 1. Familia Nymphalidae Subfamilia Apaturinae Doxocopa kallina (Staudinger, 1886). Doxocopa laure (Drury, 1776). Doxocopa lavinia (Butler, 1886). Doxocopa linda (C. Felder & R. Felder, 1860). Doxocopa pavon (Latreille, 1809). Subfamilia Nymphalinae Tribu Coeini Baetus aelius (Stoll, 1780). Baetus deucaliom (C. Felder & R. Felder, 1860). Baetus japetus (Staudinger, 1885). Colobura annulata (Willmot, Constantino & J. Hall, 2001). Colobura dirce (Linnaeus, 1758). Historis acheronta (Fabricius, 1775). Historis odius (Fabricius, 1775). Smyrna blomfilda (Fabricius, 1781). Tigridia acesta (Linnaeus, 1758). Tribu Kallimini Anartia jatrophae (Linnaeus, 1763). Junonia everate (Cramer, 1779). Junonia genoveva (Cramer, 1780). Metamorpha elissa (Hübner, 1818). Siproeta stelenes (Linnaeus, 1758). Tribu Melitaeini Eresia clio (Linnaeus, 1758). Eresia eunice (Hübner, 1807). Eresia nauplios (Linnaeus, 1758). Tegosa claudina (Escholtz, 1821). Tegosa fragilis (H. W. Bates, 1864). Tribu Nymphalini Hypanarthia lethe (Fabricius, 1793). Tribu Acraeini Actinote pellenea (Hübner, 1821). Subfamilia Charaxinae Tribu Preponini Agrias amydon (Hewitson, 1854). Agrias claudina (Godart, 1824). Archaeoprepona amphimacus (Fabricius, 1775). Archaeoprepona demophon (Linnaeus, 1758). Archaeoprepona meander (Cramer, 1775). Prepona dexamenus (Hopffer, 1874). Prepona laertes (Hübner, 1811). Prepona pheridamas (Cramer, 1777). Prepona pylene