Thomas Allan Mckay, Printer, Publisher and Entrepreneur

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ballarat 2013 Pty Douglas Stewart Fine Books Ltd Melbourne • Australia # 4074

BALLARAT 2013 PTY DOUGLAS STEWART FINE BOOKS LTD MELBOURNE • AUSTRALIA # 4074 Print Post Approved 342086/0034 Add your details to our email list for monthly New Acquisitions, visit www.DouglasStewart.com.au Ballarat Antique Fair 9-11 March 2013 # 4076 PTY DOUGLAS STEWART FINE BOOKS LTD PO Box 272 • Prahran • Melbourne • VIC 3181 • Australia • +61 3 9510 8484 [email protected] • www.DouglasStewart.com.au Some account of my doings in Australia from 1855 to 1862. REYNOLDS, Frederick AN APPARENTLY UNPUBLISHED AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL ACCOUNT OF LIFE ON THE VICTORIAN GOLDFIELDS DURING THE 1850s. Circa 1870. Manuscript written in ink on [27] pp, being one gathering from a contemporary quarto size notebook, the text complete in itself, titled on first page Some account of my doings in Australia from 1855 to 1862; written in one hand throughout and signed by the author Frederick Reynolds at the foot of the final page; beneath this signature is written in pencil in a slightly later hand (probably that of a family member) Husband of Guglielma Melford; the handwriting throughout the manuscript is bold, neat and entirely legible, and Reynolds’ expression is that of a literate, reasonably well-educated person; the thickish notepaper, of a type consistent with an 1870s dating, is toned around the edges but is extremely well preserved and shows no signs of brittleness; the black ink displays a higher level of oxidisation (ie. is slightly browner) on the exposed first page than on the inner pages of the manuscript, as should be expected. The narrative reveals that Frederick Reynolds was an English miner from Bridgewater in Somerset. -

Ed Carpenter, Artist [email protected] Commissions

ED CARPENT ER 1 Ed Carpenter, Artist [email protected] Revision 2/1/21 Born: Los Angeles, California. 1946 Education: University of California, Santa Barbara 1965-6, Berkeley 1968-71 Ed Carpenter is an artist specializing in large-scale public installations ranging from architectural sculpture to infrastructure design. Since 1973 he has completed scores of projects for public, corporate, and ecclesiastical clients. Working internationally from his studio in Portland, Oregon, USA, Carpenter collaborates with a variety of expert consultants, sub-contractors, and studio assistants. He personally oversees every step of each commission, and installs them himself with a crew of long-time helpers, except in the case of the largest objects, such as bridges. While an interest in light has been fundamental to virtually all of Carpenter’s work, he also embraces commissions that require new approaches and skills. This openness has led to increasing variety in his commissions and a wide range of sites and materials. Recent projects include interior and exterior sculptures, bridges, towers, and gateways. His use of glass in new configurations, programmed artificial lighting, and unusual tension structures have broken new ground in architectural art. He is known as an eager and open-minded collaborator as well as technical innovator. Carpenter is grandson of a painter/sculptor, and step-son of an architect, in whose office he worked summers as a teenager. He studied architectural glass art under artists in England and Germany during the early 1970’s. Information on his projects and a video about his methods can be found at: http://www.edcarpenter.net/ Commissions Bridge And Exterior Public Commissions 2019: Barbara Walker Pedestrian Bridge, Wildwood Trail, Portland, OR, 180’ x 12’ x 8’. -

Australian Poems You NEED to KNOW

1OO Australian Poems You NEED TO KNOW Edited by Jamie Grant Foreword by Phillip Adams hardiegrant books MELBOURNE-LONDON Convict and Stockrider A Convict's Tour to Hell Francis Macnamara ('Frank the Poet') 16 The Beautiful Squatter Charles Harpur 22 Taking the Census Charles R Thatcher 23 The Sick Stockrider Adam Lindsay Gordon 25 The Red Page My Other Chinee Cook James Brunton Stephens 30 Bell-birds Henry Kendall 32 Are You the Cove? Joseph Furphy ('Tom Collins') 34 How McDougal Topped the Score Thomas E Spencer 35 The Wail of the Waiter Marcus Clarke 38 Where the Pelican Builds Mary Hannay Foott 40 Catching the Coach Alfred T Chandler ('Spinifex') 41 Narcissus and Some Tadpoles Victor J Daley 44 6 i Contents Gundagai to Ironbark Nine Miles from Gundagai Jack Moses 48 The Duke of Buccleuch JA Philp 49 How We Drove the Trotter WTGoodge 50 Our Ancient Ruin 'Crupper D' 52 The Brucedale Scandal Mary Gilmore 53 Since the Country Carried Sheep Harry Morant ('The Breaker') 56 The Man from Ironbark AB Paterson (The Banjo') 58 The Old Whimrhorse Edward Dyson 60 Where the Dead Men Lie Barcroft Boake 62 Australia Bernard O'Dowd , 64 The Stockman's Cheque EW Hornung 65 The Bullocky's Love-episode AF York 67 Bastard and Bushranger «<§!> The Bastard from the Bush Anonymous 70 When your Pants Begin to Go Henry Lawson 72 The Fisher Roderic Quinn 74 The Mystery Man 'NQ' 75 Emus Mary Fullerton 76 The Death of Ben Hall Will H Ogilvie 77 The Coachman's Yarn EJ Brady 80 Fire in the Heavens, and Fire Along the Hills Christopher Brennan 83 The Orange Tree -

Rewriting Universes: Post-Brexit Futures in Dave Hutchinson’S Fractured Europe Quartet

humanities Article Rewriting Universes: Post-Brexit Futures in Dave Hutchinson’s Fractured Europe Quartet Hadas Elber-Aviram Department of English, The University of Notre Dame (USA) in England, London SW1Y 4HG, UK; [email protected] Abstract: Recent years have witnessed the emergence of a new strand of British fiction that grapples with the causes and consequences of the United Kingdom’s vote to leave the European Union. Building on Kristian Shaw’s pioneering work in this new literary field, this article shifts the focus from literary fiction to science fiction. It analyzes Dave Hutchinson’s Fractured Europe quartet— comprised of Europe in Autumn (pub. 2014), Europe at Midnight (pub. 2015), Europe in Winter (pub. 2016) and Europe at Dawn (pub. 2018)—as a case study in British science fiction’s response to the recent nationalistic turn in the UK. This article draws on a bespoke interview with Hutchinson and frames its discussion within a range of theories and studies, especially the European hermeneutics of Hans-Georg Gadamer. It argues that the Fractured Europe quartet deploys science fiction topoi to interrogate and criticize the recent rise of English nationalism. It further contends that the Fractured Europe books respond to this nationalistic turn by setting forth an estranged vision of Europe and offering alternative modalities of European identity through the mediation of photography and the redemptive possibilities of cooking. Keywords: speculative fiction; science fiction; utopia; post-utopia; dystopia; Brexit; England; Europe; Dave Hutchinson; Fractured Europe quartet Citation: Elber-Aviram, Hadas. 2021. Rewriting Universes: Post-Brexit 1. Introduction Futures in Dave Hutchinson’s Fractured Europe Quartet. -

Lorella Belli Literary Agency Ltd Lbf 2019

LORELLA BELLI LITERARY AGENCY LTD Translation Rights List LBF 2019 lbla lorella belli literary agency ltd 54 Hartford House 35 Tavistock Crescent Notting Hill London W11 1AY, UK Tel. 0044 20 7727 8547 [email protected] Lorella Belli Literary Agency Ltd. Registered in England and Wales. Company No. 11143767. Registered Office: 54 Hartford House, 35 Tavistock Crescent, Notting Hill, London W11 1AY, United Kingdom. 1 Fiction: New Titles/Authors Nisha Minhas Selected Backlist includes: Rick Mofina Taylor Adams Kirsty Moseley Renita D’Silva Ingrid Alexandra Owen Mullen Helen Durrant J A Baker Steve Parker Joy Ellis TJ Brearton Katie Stephens Charlie Gallagher Ruth Dugdall Mark Tilbury Sibel Hodge Ker Dukey Victoria Van Tiem Ana Johns Hannah Fielding Anita Waller Carol Mason Janice Frost Alex Walters Nicola May Sophie Jackson PP Wong Dreda Say Mitchell Maggie James Dylan H Jones Betsy Reavley Sharon Maas Alison J Waines Selected Bookouture authors (no new submissions, but handling existing deals/publishers only): Mandy Baggot Anna Mansell Rebecca Stonehill Robert Bryndza Angela Marsons Fiona Valpy Colleen, Coleman Helen Phifer Sue Watson Jenny Hale Helen Pollard Carol Wyer Arlene Hunt Kelly Rimmer Louise Jensen Claire Seeber Non-Fiction: New Titles Sally Corner Gerald Posner Marcus Ferrar Patricia Posner Hira Ali Tamsen Garrie Robert J Ray Nick Baldock/Bob Hayward Girl on the Net Tam Rodwell Christopher Lascelles Jonathan Sacks Selected Backlist Jeremy Leggett Grace Saunders -

The Bulletin Story Book a Selection of Stories and Literary Sketches from “The Bulletin”

The Bulletin Story Book A Selection of Stories and Literary Sketches from “The Bulletin” A digital text sponsored by Australian Literature Gateway University of Sydney Library Sydney http://purl.library.usyd.edu.au/setis/id/bulstor © University of Sydney Library. The texts and images are not to be used for commercial purposes without permission 2003 Source Text: Prepared from the print edition published by The Bulletin Newspaper Company Sydney 1902 303pp Extensive efforts have been made to track rights holders Please let us know if you have information on this. All quotation marks are retained as data. First Published: 1901 A823.8909/1 Australian Etext Collections at short stories 1890-1909 The Bulletin Story Book A Selection of Stories and Literary Sketches from “The Bulletin” Sydney The Bulletin Newspaper Company 1902 2nd Edition Prefatory THE files of The Bulletin for twenty years offer so much material for a book such as this, that it was not possible to include more than a small number of the stories and literary sketches judged worthy of republication. Consequently many excellent Australian writers are here unrepresented, their work being perforce held over for The Second Bulletin Story Book, although it is work of a quality equal to that which is now given. The risk and expense of this publication are undertaken by The Bulletin Newspaper Company, Limited. Should any profits accrue, a share of forty per cent, will be credited to the writers represented. Owing to the length of time which, in some cases, has elapsed since the original publication in The Bulletin, the names and addresses of some of the writers have been lost sight of; and their work appears over pen-names, The editor will be glad if these writers will communicate with him and assist in completing the Biographical Index at the end of the book. -

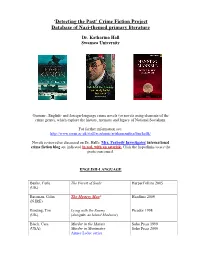

'Detecting the Past' Crime Writing Project

‘Detecting the Past’ Crime Fiction Project Database of Nazi-themed primary literature Dr. Katharina Hall Swansea University German-, English- and foreign-language crime novels (or novels using elements of the crime genre), which explore the history, memory and legacy of National Socialism. For further information see: http://www.swan.ac.uk/staff/academic/artshumanities/ltm/hallk/ Novels reviewed or discussed on Dr. Hall's 'Mrs. Peabody Investigates' international crime fiction blog are indicated in red, with an asterisk. Click the hyperlinks to see the posts concerned. ENGLISH-LANGUAGE Banks, Carla The Forest of Souls HarperCollins 2005 (UK) Bateman, Colin The Mystery Man* Headline 2009 (N.IRE) Binding, Tim Lying with the Enemy Picador 1998 (UK) (also pub. as Island Madness) Black, Cara Murder in the Marais Soho Press 1999 (USA) Murder in Montmatre Soho Press 2006 Aimee Leduc series Broderick, William The Sixth Lamentation* (see Time Warner 2004 [2003] (UK) discussion in comments section) Father Anselm series Brophy, Grace A Deadly Paradise Soho Press 2008 (US) Le Carré, John Call for the Dead* Penguin 2012 [1961] (UK) Penguin 2010 [1963] The Spy who Came in from the Cold* George Smiley #1 and #3 Sceptre 1999 [1968] A Small Town in Germany* Chabon, Michael The Final Solution Harper Perennial 2008 (USA) [2005] The Yiddish Policemen’s Union* Harper Perennial 2008 [2007] Cook, Thomas H. Instruments of Night Bantam 1999 (USA) Crispin, Edmund Holy Disorders Vintage 2007 [1946] (UK) Crombie, Deborah Where Memories Lie Macmillan 2009 [2008] -

Australian Elegy: Landscape and Identity

Australian Elegy: Landscape and Identity by Janine Gibson BA (Hons) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of (Doctor of Philosophy) Deakin University December, 2016 Acknowledgments I am indebted to the School of Communication and Creative Arts at Deakin University (Geelong), especially to my principal supervisor Professor David McCooey whose enthusiasm, constructive criticism and encouragement has given me immeasurable support. I would like to gratefully acknowledge my associate supervisors Dr. Maria Takolander and Dr. Ann Vickery for their interest and invaluable input in the early stages of my thesis. The unfailing help of the Library staff in searching out texts, however obscure, as well as the support from Matt Freeman and his helpful staff in the IT Resources Department is very much appreciated. Sincere thanks to the Senior HDR Advisor Robyn Ficnerski for always being there when I needed support and reassurance; and to Ruth Leigh, Kate Hall, Jo Langdon, Janine Little, Murray Noonan and Liam Monagle for their help, kindness and for being so interested in my project. This thesis is possible due to my family, to my sons Luke and Ben for knowing that I could do this, and telling me often, and for Jane and Aleisha for caring so much. Finally, to my partner Jeff, the ‘thesis watcher’, who gave me support every day in more ways than I can count. Abstract With a long, illustrious history from the early Greek pastoral poetry of Theocritus, the elegy remains a prestigious, flexible Western poetic genre: a key space for negotiating individual, communal and national anxieties through memorialization of the dead. -

Architecture

ARCHITECTURE TITLE AUTHOR/EDITOR PUBLISHER DATE 1982 Calendar of Bucks County Architecture (3 copies) Bucks County 1982 1983 Calendar of Bucks County Architecture Conservancy 1983 1987 Calendar of Bucks County Architecture (2 copies) 1987 1988 Calendar of Bucks County Architecture (2 copies) 1988 1992 Calendar of Bucks County Architecture --Historic 1992 Schoolhouses of Bucks County (2 copies) Architectural Treasures of Early America--Survey of Early Staff of the Early American Arno Press 1977 American Design Society Architecture in America—Volume I Smith, G. E. Kidder American Heritage 1976 Publishing Co. Architecture in America—Volume II Smith, G. E. Kidder American Heritage 1976 Publishing Co. Architecture in Early New England Cummings, Abbott Lowell The Meridon Gravure Co. 1974 Clues to American Architecture Klein, Marilyn W., and Starrhill Press 1985 David P Fogle Conservation News, Volume 17, Number 3 (Featuring The Bucks County 1984 Victorian Architecture of Bucks County) Conservancy Design Resources of Doylestown Doylestown Township 1969 Planning Commission A Dictionary of Architecture Pevsner, Nikolaus, John The Overlook Press 1976 Fleming, and Hugh Honour 4/27/2009 1 ARCHITECTURE TITLE AUTHOR/EDITOR PUBLISHER DATE Early Domestic Architecture of Connecticut Kelly, J. Frederick Dover Publications. 1952 Early Domestic Architecture of Pennsylvania (2 copies) Raymond, Eleanor Schiffer Publishing 1977 A Field Guide to American Architecture Rifkind, Carole New American Library 1980 Pennsylvania Architecture—The Historic American Burns, Deborah Stephens, Commonwealth of 2000 Buildings Survey 1933-1990 and Richard J. Webster Pennsylvania; Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission Pennsylvania School of Architecture Burrowes, Thomas H. Commonwealth of 1856 Pennsylvania Tidewater Maryland Architecture and Gardens Forman, Henry Chandlee Bonanza Books 1956 Victorian Architecture Bicknell, A. -

The Extraordinary Flight of Book Publishing's Wingless Bird

LOGOS 12(2) 3rd/JH 1/11/06 9:46 am Page 70 LOGOS The extraordinary flight of book publishing’s wingless bird Eric de Bellaigue “Very few great enterprises like this survive their founder.” The speaker was Allen Lane, the founder of Penguin, the year before his death in 1970. Today the company that Lane named after the wingless bird has soared into the stratosphere of the publishing world. How this was achieved, against many obstacles and in the face of many setbacks, invites investigation. Eric de Bellaigue has been When Penguin Books was floated on the studying the past and forecasting Stock Exchange in April 1961, it already had the future of British book twenty-five profitable years behind it. The first ten Penguin reprints, spearheaded by André Maurois’ publishing for thirty-five years. Ariel and Ernest Hemingway’s Farewell to Arms, In this first instalment of a study came out in 1935 under the imprint of The Bodley of Penguin Books, he has Head, but with Allen Lane and his two brothers combined his financial insights underwriting the venture. In 1936, Penguin Books Limited was incorporated, The Bodley Head having with knowledge gleaned through been placed into voluntary receivership. interviews with many who played The story goes that the choice of the parts in Penguin’s history. cover price was determined by Woolworth’s slogan Subsequent instalments will bring “Nothing over sixpence”. Woolworths did indeed de Bellaigue’s account up to the stock the first ten titles, but Allen Lane attributed his selection of sixpence as equivalent to a packet present day. -

Asian Art Books.Xlsx

The FloatingWorld The Story of Japanese Prints By James A. Michener 1954 Random House LOC 54-7812 1st Printng Chinoiserie Dawn Jacobson Phaidon Press Ltd London ISBN 0-714828831 1993 Dust Jacket Chinese Calligraphy Tseng Yu-ho Ecke Philadelphia Museum of Art 1971 1971 LOC 75-161453 Second Printing Soft Cover Treasures of Asia Chinese Painting Text by James Cahill James Cahill The World Publishing Co. Cleveland Copyright by Editions d'Art Albert Skira, 1960 LOC 60- 15594 Painting in the Far East Laurence Binyon 3rd Edition Revised Throughout Dova Publication, NY Soft Cover The Year One Art of the Ancient World East and West The Metropolitan Museum of Art Edited by Elizabeth J. Milleker Yale University Press 2000 Dust Jacket A Shoal of Fishes Hiroshige The Metropolitan Museum of Art The Viking Press Studio Book 1980 LOC 80-5170 ISBN 0-87099-237-6 Sleeve Past, Present, East and West Sherman E. Lee George Braziller, Inc. New York 1st Printing ISBN 0-8076-1064-x Dust Jacket Birds, Beast, Blossoms, and Bugs The Nature of Japan Text by Harold P. Stern Harry N. Abrams, Inc. LOC 75-46630 Cultural Relics Unearted in China 1973 Wenwu Press Peking, 1972 w/ intro in English- Translation of the Intro and the Contents of: Cultural Relics Unearthed During the Period of the Great Cultural Revolution prepared by China Books & Periodicals Dust Jacket & Sleeve Chinese Art and Culture Rene Grousset Translated from the Frenchby Haakon Chevalier E-283 1959 Orion Press, Inc. Paper Second Printing Chinese Bronzes 70 Plates in Full Colour Mario Bussagli Translated by Pamela Swinglehurst from the Italian original Bronzi Cinesi 1969 The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited Dust Jacket Chinese Art from the Cloud Wampler and other Collections in the Everson Museum Intro by Max Loehr Handbook of the collection by Celia Carrington Riely Frederick A . -

E 344L — 34495 Australian Literature and Film Fall 2015, T Th 3:30-4:45 P.M

E 344L — 34495 Australian Literature and Film Fall 2015, T Th 3:30-4:45 p.m. COURSE SYLLABUS 344L Australian Literature and Film: A representative selection of Australian writing and films from the founding, 1788, to the present. Prerequisite: Nine semester hours of course work in English or rhetoric or writing. The subject of each class meeting may be determined from the assigned reading for the day (see following). Prerequisites: 9 semester hours of coursework in English, Rhetoric, or Writing Required Texts o Australian Literature and Film — Co-op Packet o Robyn Davidson, Tracks (separate text) o Kate Jennings, Snake — Co-op Packet Have completed readings by their assigned date and come prepared for class discussion. This is an all-important important component in your class participation percentage; see below. Films — We will see a 60 minute documentary and five full-length feature films as well as scenes from one television miniseries—40,000 Years of Dreaming: The History of Australian Cinema; Walkabout; The Tracker; Muriel’s Wedding; On the Beach; & Mad Max: Fury Road. Please note that it is vital for us to see the films in class and as a class; they will be accompanied by lecture/commentary. Grading Policy and Percentages: Because participation contributes to your grade, attendance is strongly encouraged. Grades will be determined on the following basis: Mid-Term Exam 25% Tuesday, October 27th Exam 2/Final Exam* 30% Thursday, December 3rd Essay 25% Due date tba Class Participation 20% Attendance, participation, curiousity & focus for things Australian! * Plus and minus grades will be given in this class.