Download 296796.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SOUTHERN LIGHTS Depiction of a Tibetan Globe-Lamp

\ I I SOUTHERN LIGHTS Depiction of a Tibetan globe-lamp. The four swivelling concentric rings serve to hold the lamp in place, always keeping it upright. The lamp was popularized in the 16th century by Girolamo Cardano, whose name was given to its method of suspension. Its first appearance in Europe can be traced to the 9th century; however, it was in China over 1 000 years earlier, in the 2nd century BC, that the lamp was invented. SOUTHERN LIGHTS Celebrating the Scientific Achievements of the Developing World DAVID SPURGEON INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT RESEARCH CENTRE Ottawa • Cairo • Dakar • Johannesburg • Montevideo • Nairobi New Delhi • Singapore Published by the International Development Research Centre P0 Box 8500, Ottawa, ON, Canada K1G 3H9 © International Development Research Centre 1995 Spurgeon, D. Southern lights celebrating the scientific achievements of the developing world. Ottawa, ON, IDRC, 1995. ix + 137 p. !Scientific discoveries!, !scientific progress!, /technological change!, !research and development!, /developing countries! — !North South relations!, !traditional technology!, !international cooperation!, /comparative analysis!, /case studies!, references. UDC: 608.1 ISBN: 0-88936-736-1 A microfiche edition is available. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the International Development Research Centre. IDRC BOOKS endeavours to produce -

Ed Carpenter, Artist [email protected] Commissions

ED CARPENT ER 1 Ed Carpenter, Artist [email protected] Revision 2/1/21 Born: Los Angeles, California. 1946 Education: University of California, Santa Barbara 1965-6, Berkeley 1968-71 Ed Carpenter is an artist specializing in large-scale public installations ranging from architectural sculpture to infrastructure design. Since 1973 he has completed scores of projects for public, corporate, and ecclesiastical clients. Working internationally from his studio in Portland, Oregon, USA, Carpenter collaborates with a variety of expert consultants, sub-contractors, and studio assistants. He personally oversees every step of each commission, and installs them himself with a crew of long-time helpers, except in the case of the largest objects, such as bridges. While an interest in light has been fundamental to virtually all of Carpenter’s work, he also embraces commissions that require new approaches and skills. This openness has led to increasing variety in his commissions and a wide range of sites and materials. Recent projects include interior and exterior sculptures, bridges, towers, and gateways. His use of glass in new configurations, programmed artificial lighting, and unusual tension structures have broken new ground in architectural art. He is known as an eager and open-minded collaborator as well as technical innovator. Carpenter is grandson of a painter/sculptor, and step-son of an architect, in whose office he worked summers as a teenager. He studied architectural glass art under artists in England and Germany during the early 1970’s. Information on his projects and a video about his methods can be found at: http://www.edcarpenter.net/ Commissions Bridge And Exterior Public Commissions 2019: Barbara Walker Pedestrian Bridge, Wildwood Trail, Portland, OR, 180’ x 12’ x 8’. -

Rewriting Universes: Post-Brexit Futures in Dave Hutchinson’S Fractured Europe Quartet

humanities Article Rewriting Universes: Post-Brexit Futures in Dave Hutchinson’s Fractured Europe Quartet Hadas Elber-Aviram Department of English, The University of Notre Dame (USA) in England, London SW1Y 4HG, UK; [email protected] Abstract: Recent years have witnessed the emergence of a new strand of British fiction that grapples with the causes and consequences of the United Kingdom’s vote to leave the European Union. Building on Kristian Shaw’s pioneering work in this new literary field, this article shifts the focus from literary fiction to science fiction. It analyzes Dave Hutchinson’s Fractured Europe quartet— comprised of Europe in Autumn (pub. 2014), Europe at Midnight (pub. 2015), Europe in Winter (pub. 2016) and Europe at Dawn (pub. 2018)—as a case study in British science fiction’s response to the recent nationalistic turn in the UK. This article draws on a bespoke interview with Hutchinson and frames its discussion within a range of theories and studies, especially the European hermeneutics of Hans-Georg Gadamer. It argues that the Fractured Europe quartet deploys science fiction topoi to interrogate and criticize the recent rise of English nationalism. It further contends that the Fractured Europe books respond to this nationalistic turn by setting forth an estranged vision of Europe and offering alternative modalities of European identity through the mediation of photography and the redemptive possibilities of cooking. Keywords: speculative fiction; science fiction; utopia; post-utopia; dystopia; Brexit; England; Europe; Dave Hutchinson; Fractured Europe quartet Citation: Elber-Aviram, Hadas. 2021. Rewriting Universes: Post-Brexit 1. Introduction Futures in Dave Hutchinson’s Fractured Europe Quartet. -

August 1, 2019 Mr. John Sargent, Chief Executive Officer Macmillan Publishers 120 Broadway Street New York, NY 10271

50 E. Huron, Chicago, IL 60611 August 1, 2019 Mr. John Sargent, Chief Executive Officer Macmillan Publishers 120 Broadway Street New York, NY 10271 Dear Mr. Sargent, On behalf of the 9,000 members of the Public Library Association (PLA), our nation’s largest association for public library professionals, we are writing to object to and ask Macmillan Publishers to reconsider its plan to embargo new eBook titles for U.S. public libraries starting November 1. Under this new model, we understand a public library may purchase only a single copy of each new title in eBook format upon release, after which Macmillan will impose an eight-week embargo on additional eBook sales of that title. To public libraries and the millions of people who rely on them every day, Macmillan’s new policy is patently unacceptable. The central mission of libraries is to ensure equitable access to information for all people, regardless of format. Macmillan’s new eBook lending policy will limit access to new titles by the readers who depend most on libraries. In a recent interview, you likened this embargo to delaying release of paperback titles to maximize hardcover sales, but in that case public libraries are able to purchase and lend the books at the same time our readers are seeking them. Access to eBooks through public libraries should not be denied or delayed. PLA and its parent organization the American Library Association, will explore all possible avenues to ensure that libraries can do our jobs of providing access to information for all, without arbitrary limitations that undermine libraries’ ability to serve our communities. -

Lorella Belli Literary Agency Ltd Lbf 2019

LORELLA BELLI LITERARY AGENCY LTD Translation Rights List LBF 2019 lbla lorella belli literary agency ltd 54 Hartford House 35 Tavistock Crescent Notting Hill London W11 1AY, UK Tel. 0044 20 7727 8547 [email protected] Lorella Belli Literary Agency Ltd. Registered in England and Wales. Company No. 11143767. Registered Office: 54 Hartford House, 35 Tavistock Crescent, Notting Hill, London W11 1AY, United Kingdom. 1 Fiction: New Titles/Authors Nisha Minhas Selected Backlist includes: Rick Mofina Taylor Adams Kirsty Moseley Renita D’Silva Ingrid Alexandra Owen Mullen Helen Durrant J A Baker Steve Parker Joy Ellis TJ Brearton Katie Stephens Charlie Gallagher Ruth Dugdall Mark Tilbury Sibel Hodge Ker Dukey Victoria Van Tiem Ana Johns Hannah Fielding Anita Waller Carol Mason Janice Frost Alex Walters Nicola May Sophie Jackson PP Wong Dreda Say Mitchell Maggie James Dylan H Jones Betsy Reavley Sharon Maas Alison J Waines Selected Bookouture authors (no new submissions, but handling existing deals/publishers only): Mandy Baggot Anna Mansell Rebecca Stonehill Robert Bryndza Angela Marsons Fiona Valpy Colleen, Coleman Helen Phifer Sue Watson Jenny Hale Helen Pollard Carol Wyer Arlene Hunt Kelly Rimmer Louise Jensen Claire Seeber Non-Fiction: New Titles Sally Corner Gerald Posner Marcus Ferrar Patricia Posner Hira Ali Tamsen Garrie Robert J Ray Nick Baldock/Bob Hayward Girl on the Net Tam Rodwell Christopher Lascelles Jonathan Sacks Selected Backlist Jeremy Leggett Grace Saunders -

Fall Conference

NAIBA Fall Conference October 6 - October 8, 2018 Baltimore, MD CONTENTS NAIBA Board of Directors 1 NOTES Letters from NAIBA’s Presidents 2 REGISTRATION HOURS Benefits of NAIBA Membership 4 Schedule At A Glance 6 Constellation Foyer Detailed Conference Schedule 8 Saturday, October 6, Noon – 7:00pm Sunday, October 7, 7:30am – 7:00pm Exhibition Hall Map 23 Monday, October 8, 7:30am – 1:00pm Conference Exhibitors 24 Thank You to All Our Sponsors 34 Were You There? 37 EXHIBIT HALL HOURS Publishers Marketplace Sunday, October 7, 2:00pm – 6:00pm ON BEING PHOTOGRAPHED Participating in the NAIBA Fall Conference and entering any of its events indicates your agreement to be filmed or photographed for NAIBA’s purposes. NO CARTS /naiba During show hours, no hand carts or other similar wheeled naibabooksellers devices are allowed on the exhibit floor. @NAIBAbook #naiba CAN WE TALK? The NAIBA Board Members are happy to stop and discuss retail and association business with you. Board members will be wearing ribbons on their badges to help you spot them. Your input is vital to NAIBA’s continued growth and purpose. NAIBA BOARD OF DIRECTORS Todd Dickinson Trish Brown Karen Torres (Outgoing President) One More Page Hachette Book Group Aaron’s Books 2200 N. Westmoreland Street 1290 6th Ave. 35 East Main Street Arlington, VA 22213 New York, NY 10104 Lititz, PA 17543 Ph: 703-861-8326 212-364-1556 Ph: 717-627-1990 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Jenny Clines Stephanie Valdez Bill Reilly (Incoming Board member) (Outgoing Board member) (Incoming President) Politics & Prose 143 Seventh Ave. -

'Detecting the Past' Crime Writing Project

‘Detecting the Past’ Crime Fiction Project Database of Nazi-themed primary literature Dr. Katharina Hall Swansea University German-, English- and foreign-language crime novels (or novels using elements of the crime genre), which explore the history, memory and legacy of National Socialism. For further information see: http://www.swan.ac.uk/staff/academic/artshumanities/ltm/hallk/ Novels reviewed or discussed on Dr. Hall's 'Mrs. Peabody Investigates' international crime fiction blog are indicated in red, with an asterisk. Click the hyperlinks to see the posts concerned. ENGLISH-LANGUAGE Banks, Carla The Forest of Souls HarperCollins 2005 (UK) Bateman, Colin The Mystery Man* Headline 2009 (N.IRE) Binding, Tim Lying with the Enemy Picador 1998 (UK) (also pub. as Island Madness) Black, Cara Murder in the Marais Soho Press 1999 (USA) Murder in Montmatre Soho Press 2006 Aimee Leduc series Broderick, William The Sixth Lamentation* (see Time Warner 2004 [2003] (UK) discussion in comments section) Father Anselm series Brophy, Grace A Deadly Paradise Soho Press 2008 (US) Le Carré, John Call for the Dead* Penguin 2012 [1961] (UK) Penguin 2010 [1963] The Spy who Came in from the Cold* George Smiley #1 and #3 Sceptre 1999 [1968] A Small Town in Germany* Chabon, Michael The Final Solution Harper Perennial 2008 (USA) [2005] The Yiddish Policemen’s Union* Harper Perennial 2008 [2007] Cook, Thomas H. Instruments of Night Bantam 1999 (USA) Crispin, Edmund Holy Disorders Vintage 2007 [1946] (UK) Crombie, Deborah Where Memories Lie Macmillan 2009 [2008] -

Don Weisberg Appointed President of Macmillan Publishers U.S

DON WEISBERG APPOINTED PRESIDENT OF MACMILLAN PUBLISHERS U.S. Macmillan announces today the appointment of Don Weisberg as President of Macmillan Publishers US. In this role, Weisberg will manage the U.S. trade publishing houses of Macmillan, the audio and podcast businesses, and the trade sales organization. He will report to Macmillan CEO John Sargent. The appointment will have no effect on the reporting responsibilities of Andrew Weber, Macmillan's COO, or Ken Michaels, the CEO of Macmillan Learning, who continue to report to Sargent. Weisberg will join Macmillan at the beginning of January 2016. Sargent stated, "Macmillan Publishers has grown significantly over the past years, and the publishing business continues to increase in complexity. Our business in the United States has expanded greatly even as we have become more integrated globally. As my role has changed, it is clear that the U.S. business needs a dedicated senior executive to lead our publishing efforts. I am delighted to welcome Don Weisberg to Macmillan. Don has a remarkable track record of success across many aspects of the publishing business, and his unique combination of skills and management style are a perfect fit for our organization. Don is smart and experienced. He has proven to be great leader with a true passion for books and the book business. He will bring tremendous focus and energy to our publishing, to the great benefit of our company and our authors." Weisberg said, "As difficult as it will be to leave my team and authors at Penguin Young Readers, I am greatly looking forward to working with the group at Macmillan that I have always admired from afar. -

Tor Teen Acquires Ya Contemporary Fantasy Trilogy from Debut Black Author, Terry J

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: Saraciea Fennell, Publicity Manager, Tor Teen [email protected] TOR TEEN ACQUIRES YA CONTEMPORARY FANTASY TRILOGY FROM DEBUT BLACK AUTHOR, TERRY J. BENTON IN MID-SIX FIGURE DEAL NEW YORK, NY (December 3, 2020)—Tor Teen, the publisher of A Song Below Water and The Witchlands series, has acquired, in a major deal, Blood Debts, a YA contemporary fantasy trilogy by Terry J. Benton, pitched as “Dynasty with magic” set to publish in Winter 2023. The book follows two Black twins, sixteen year-old Clem and Cristina, who must put aside their differences and reunite their fractured family in order to take back the New Orleans magic council their family used to rule—all while solving a decades-old murder that sparked the rising tensions between the city’s magical and non-magical communities, before it leads to an all-out war. Tor Teen Senior Editor Ali Fisher said, “Reading Blood Debts was like binge-watching my new favorite show. I gasped, I laughed, I completely fell in love. Benton is a powerhouse new voice in YA fantasy and the relationship between race, magic, and power is fresh and observant. I was on the edge of my seat to see who'd claim the throne!” Benton's agent, Patrice Caldwell, praises the hole the book fills in the market: “I can’t think of the last YA contemporary fantasy I’ve read written by a gay, Black man, centering a gay, Black boy. I can’t wait for this book to be out in the world!” Patrice Caldwell at New Leaf Literary & Media negotiated the three book deal for North American rights. -

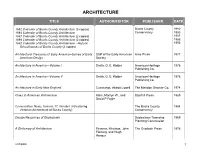

Architecture

ARCHITECTURE TITLE AUTHOR/EDITOR PUBLISHER DATE 1982 Calendar of Bucks County Architecture (3 copies) Bucks County 1982 1983 Calendar of Bucks County Architecture Conservancy 1983 1987 Calendar of Bucks County Architecture (2 copies) 1987 1988 Calendar of Bucks County Architecture (2 copies) 1988 1992 Calendar of Bucks County Architecture --Historic 1992 Schoolhouses of Bucks County (2 copies) Architectural Treasures of Early America--Survey of Early Staff of the Early American Arno Press 1977 American Design Society Architecture in America—Volume I Smith, G. E. Kidder American Heritage 1976 Publishing Co. Architecture in America—Volume II Smith, G. E. Kidder American Heritage 1976 Publishing Co. Architecture in Early New England Cummings, Abbott Lowell The Meridon Gravure Co. 1974 Clues to American Architecture Klein, Marilyn W., and Starrhill Press 1985 David P Fogle Conservation News, Volume 17, Number 3 (Featuring The Bucks County 1984 Victorian Architecture of Bucks County) Conservancy Design Resources of Doylestown Doylestown Township 1969 Planning Commission A Dictionary of Architecture Pevsner, Nikolaus, John The Overlook Press 1976 Fleming, and Hugh Honour 4/27/2009 1 ARCHITECTURE TITLE AUTHOR/EDITOR PUBLISHER DATE Early Domestic Architecture of Connecticut Kelly, J. Frederick Dover Publications. 1952 Early Domestic Architecture of Pennsylvania (2 copies) Raymond, Eleanor Schiffer Publishing 1977 A Field Guide to American Architecture Rifkind, Carole New American Library 1980 Pennsylvania Architecture—The Historic American Burns, Deborah Stephens, Commonwealth of 2000 Buildings Survey 1933-1990 and Richard J. Webster Pennsylvania; Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission Pennsylvania School of Architecture Burrowes, Thomas H. Commonwealth of 1856 Pennsylvania Tidewater Maryland Architecture and Gardens Forman, Henry Chandlee Bonanza Books 1956 Victorian Architecture Bicknell, A. -

The Extraordinary Flight of Book Publishing's Wingless Bird

LOGOS 12(2) 3rd/JH 1/11/06 9:46 am Page 70 LOGOS The extraordinary flight of book publishing’s wingless bird Eric de Bellaigue “Very few great enterprises like this survive their founder.” The speaker was Allen Lane, the founder of Penguin, the year before his death in 1970. Today the company that Lane named after the wingless bird has soared into the stratosphere of the publishing world. How this was achieved, against many obstacles and in the face of many setbacks, invites investigation. Eric de Bellaigue has been When Penguin Books was floated on the studying the past and forecasting Stock Exchange in April 1961, it already had the future of British book twenty-five profitable years behind it. The first ten Penguin reprints, spearheaded by André Maurois’ publishing for thirty-five years. Ariel and Ernest Hemingway’s Farewell to Arms, In this first instalment of a study came out in 1935 under the imprint of The Bodley of Penguin Books, he has Head, but with Allen Lane and his two brothers combined his financial insights underwriting the venture. In 1936, Penguin Books Limited was incorporated, The Bodley Head having with knowledge gleaned through been placed into voluntary receivership. interviews with many who played The story goes that the choice of the parts in Penguin’s history. cover price was determined by Woolworth’s slogan Subsequent instalments will bring “Nothing over sixpence”. Woolworths did indeed de Bellaigue’s account up to the stock the first ten titles, but Allen Lane attributed his selection of sixpence as equivalent to a packet present day. -

Music Training Aids Speech Processing

RESEARCH HIGHLIGHTS THIS WEEK MARINE ECOLOGY these differences, suggesting that these compounds could be Blue whales mediating the effects on Popular articles SOCIAL SELECTION on social media bounce back gut flora and the immune system. A population of blue whales Sci. Transl. Med. 6, 252ra120 The language of deception has reached pre-whaling levels (2014) and is no longer endangered. A PLoS ONE paper on language patterns in fraudulent papers Cole Monnahan at the NEUROSCIENCE has sparked social-media speculation about new ways to spot University of Washington dishonest work. Researchers at Cornell University in Ithaca, in Seattle and his colleagues Music training aids New York, took advantage of a singular resource to study the modelled a population of speech processing linguistics of fraud: the collected works of Diederik Stapel, blue whales (Balaenoptera a Dutch social psychologist who confessed to faking data in musculus) in the eastern North The more music training many of his papers. The Cornell team analysed papers that had Pacific along with the number children receive, the better been deemed fraudulent by three investigative committees, of ships and their collisions their brains become at and compared them with his genuine publications. They with the mammals between distinguishing between similar found that the falsified papers had a linguistic signature. 1905 and 2050. They found speech sounds. Among other things, they tended to have fewer qualifying that whale numbers in this Nina Kraus at Northwestern words (such as ‘possibly’) and more amplifying words such as region were at their lowest in University in Evanston, ‘extremely’. “Lucky he had enough false papers for analysis!” 1931 and have since increased Illinois, and her colleagues tweeted Grace Lindsay, a neuroscience graduate student at to about 2,200 — nearly the studied children aged six to Columbia University in New York City.