Alone in the Wilderness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Duncan Public Library Board of Directors Meeting Minutes June 23, 2020 Location: Duncan Public Library

Subject: Library Board Meeting Date: August 25, 2020 Time: 9:30 am Place: Zoom Meeting 1. Call to Order with flag salute and prayer. 2. Read minutes from July 28, 2020, meeting. Approval. 3. Presentation of library statistics for June. 4. Presentation of library claims for June. Approval. 5. Director’s report a. Summer reading program b. Genealogy Library c. StoryWalk d. Annual report to ODL e. Sept. Library Card Month f. DALC grant for Citizenship Corner g. After-school snack program 6. Consider a list of withdrawn items. Library staff recommends the listed books be declared surplus and be donated to the Friends of the Library for resale, and the funds be used to support the library. 7. Consider approving creation of a Student Library Card and addition of policy to policy manual. 8. Old Business 9. New Business 10. Comments a. By the library staff b. By the library board c. By the public 11. Adjourn Duncan Public Library Claims for July 1 through 31, 2020 Submitted to Library Board, August 25, 2020 01-11-521400 Materials & Supplies 20-1879 Demco......................................................................................................................... $94.94 Zigzag shelf, children’s 20-2059 Quill .......................................................................................................................... $589.93 Tissue, roll holder, paper, soap 01-11-522800 Phone/Internet 20-2222 AT&T ........................................................................................................................... $41.38 -

Guide to Teaching Reading and Literature, Kindergarten

REPORT RESUMES ED 014 480 TE 000 082 GUIDE TO TEACHING READING AND LITERATURE,KINDERGARTEN GRADE SIX. BY- WARWICK, EUNICE AND OTHERS MADISON PUBLIC SCHOOLS, WIS. PUB DATE 64 EDRS PRICE MF -$0.50 HC -$4.44 109P. DESCRIPTORS- *CURRICULUM GUIDES, *ELEMENTARY GRADES,*ENGLISH INSTRUCTION, *LITERATURE PROGRAMS, *READING PROGRAMS,READING READINESS, READING SKILLS, READING COMPREHENSION, WORD RECOGNITION, ORAL. READING, STUDY SKILLS, INTERPRETIVESKILLS, MADISON, WISCONSIN THE MADISON, WISCONSIN, CURRICULUM GUIDE FOR THE TEACHING OF READING AND LITERATURE IN KINDERGARTENTHROUGH GRADE SIX IS DIVIDED INTO THREE PARTS. PART 1 CONTAINSTHE MADISON POINT OF VIEW CONCERNING READING ANDLITERATURE IN THE ELEMENTARY SCHOOLS, AND PROVIDES FLOW CHARTS TO HELPTHE TEACHER PERCEIVE THE TOTAL READING AND LITERATUREPROGRAM. GRADE -LEVEL EXPECTANCIES IN THE TEACHING OF READINGARE LISTED FOR THE AREAS OF WORD RECOGNITION,COMPREHENSION, ORAL READING, AND STUDY SKILLS. READING EXPECTANCIES FOR INTERPRETIVE SKILLS ARE ADDED FOR GRADES FOUR THROUGHSIX. FOR THE TEACHING OF LITERATURE, GRADE -LEVELEXPECTANCIES ARE LISTED FOR THE AREAS OF LITERATURE AIMS, TYPES,AND .ACTIVITIES. PART 2 INDICATES MORE SPECIFICEXPECTANCIES FOR EACH GRADE LEVEL IN THE TEACHING OF READING ANDLITERATURE. IN ADDITION, LISTS OF SUGGESTED MATERIALS FORTEACHING LITERATURE - -ONE EACH FOR GRADES KINDERGARTEN AND ONE,FOR TWO AND THREE, FOR FOUR AND FIVE, AND FOR SIX AND ADVANCED PUPILS- -ARE FROVIDED. FART 3 INCLUDES SUGGESTEDACTIVITIES FOR DEVELOPING READING READINESS IN KINDERGARTEN, AFLOW CHART -

Courts-Metrages

COURTS-METRAGES vieux dessins animés libres de droits (Popeye, Tom et Jerry, Superman…) : https://archive.org/details/animationandcartoons page d’accueil (adultes et enfants (films libres de droit) : https://www.apar.tv/cinema/700-films-rares-et-gratuits-disponibles-ici-et-maintenant/ page d’accueil : https://films-pour-enfants.com/tous-les-films-pour-enfants.html page d’accueil : https://creapills.com/courts-metrages-animation-compilation-20200322 SELECTION Un film pour les passionnés de cyclisme et les nostalgiques des premiers Tours de France. L'histoire n'est pas sans rappeler la réelle mésaventure du coureur cycliste français Eugène Christophe pendant la descente du col du Tourmalet du Tour de France 1913. Eugène Christophe cassa la fourche de son vélo et marcha 14 kilomètres avant de trouver une forge pour effectuer seul la réparation, comme l'imposait le règlement du Tour. Les longues moustaches du héros sont aussi à l'image d'Eugène Christophe, surnommé "le Vieux Gaulois". (7minutes , comique) https://films-pour-enfants.com/fiches-pedagogiques/14.html pickpocket Une course-poursuite rocambolesque. (1minute 27) https://films-pour-enfants.com/fiches-pedagogiques/korobushka.html salles gosses (1 minutes 30) Oui, les rapaces sont des oiseaux prédateurs et carnivores ! Un film comique et un dénouement surprenant pour expliquer aux enfants l'expression "être à bout de nerfs". https://films-pour-enfants.com/fiches-pedagogiques/sales-gosses.html i am dyslexic (6 minutes 20) Une montagne de livres ! Une très belle métaphore de la dyslexie et des difficultés que doivent surmonter les enfants dyslexiques. https://films-pour-enfants.com/fiches-pedagogiques/i-am-dyslexic.html d'une rare crudité et si les plantes avaient des sentiments (7 minutes 45) Un film étrange et poétique, et si les plantes avaient des sentiments. -

Appendix:Bookstoreadaloud

Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen Appendix: Books to Read Aloud This list is adapted from the All of these books are excellent read-aloud choices for children of all ages. With ReadyReaders website. each title is a brief summary. A Chair for My Mother, Vera B. Williams. A Caldecott Honor book, this is a warm, simple, engagingly illustrated story about a family with strong bonds. A fire destroys their old furniture, and three generations come together—a child, her mother, and her grandmother—to save their money in order to buy a new easy chair. AHatforMinervaLouise,JaneyMorganStoeke.Ahenfeelscold,butshewants to stay outside in the snow, so she goes searching for warm things. Some of the things she finds are ridiculous (a garden hose, a pot), and even the warm things are funny—mittens on her head and tail. A-Hunting We Will Go!, Steven Kellogg. A lively, funny song-story with amus- ing, detailed pictures to read and/or sing aloud. A sister and brother try to put off going to bed by singing a song that takes them on an imaginary trip. They meet a moose and a goose on the loose, a weasel at an easel, and finally—after hugs and kisses—it’s off to sleep they go! All By Myself, Mercer Mayer. Most of the “little critter” books are very popular with preschool children. In this one, the hero learns how to do things like get dressed, brush his teeth, etc., all by himself. All the Colors of the Earth, Sheila Hamanaka. A wonderful book about diversity. -

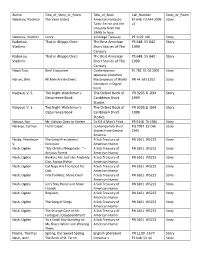

Nabokov, Vladimir That in Aleppo Once the Best American Short

Author Title_of_Story_or_Poem Title_of_Book Call_Number Story_or_Poem Nabokov, Vladimar The Vane Sisters American Fantastic PS 648 .F3 A44 2009 Story Tales: Terror and the v2 Uncanny from the 1940s to Now Nabokov, Vladimir Lance A College Treasury PE 1122 .J66 Story Nabokov, That in Aleppo Once The Best American PS 648 .S5 B42 Story Vladimir Short Stories of The 1999 Century Nabokov, That in Aleppo Once The Best American PS 648 .S5 B42 Story Vladimir Short Stories of The 1999 Century Nagai Taso Brief Encounter Contemporary PL 782 .E1 C6 2005 Story Japanese Literature Nai -an, Shih All Men Are Brothers Masterpieces of World PN 44 .M3 1952 Story Literature in Digest Form Naipaul, V. S. The Night Watchman’s The Oxford Book of PR 9205.8 .O94 Story Occurrence Book Caribbean Short 1999 Stories Naipaul, V. S. The Night Watchman’s The Oxford Book of PR 9205.8 .O94 Story Occurrence Book Caribbean Short 1999 Stories Nakasa, Nat Mr. Nakasa Goes to Harlem To Kill A Man’s Prid e PR 9348 .T6 1984 Story Naranjo, Carmen Floral Caper Contemporary Short PQ 7087 .E5 C66 Story Stories from Central 1994 America Nasby, Petroleum The Great Presidential A Sub Treasury of PN 6161 .W5223 Story V. Excursion American Humor Nash, Ogden “My Child Is Phlegmatic…” – A Sub Treasury of PN 6161 .W5223 Story Anxious Parent American Humor Nash, Ogden Bankers Are Just Like Anybody A Sub Treasury of PN 6161 .W5223 Story Else, Except Richer American Humor Nash, Ogden Cat Naps Are Too Good for A Sub Treasury of PN 6161 .W5223 Story Cats American Humor Nash, Ogden First Families, Move Over! A Sub Treasury of PN 6161 .W5223 Story American Humor Nash, Ogden Let’s Stay Home and Make A Sub Treasury of PN 6161 .W5223 Story Friends American Humor Nash, Ogden Requiem A Sub Treasury of PN 6161 .W5223 Story American Humor Nash, Ogden The Song of Songs A Sub Treasury of PN 6161 .W5223 Story American Humor Nash, Ogden The Strange Case of Mr. -

Meiermovies Short Films A-Z

MeierMovies Short Films A-Z Theatrically released motion pictures of 40 minutes or less Before perusing this list, I suggest reading my introduction to short films at the beginning of my By Star Rating list. That introduction will help explain my star choices and criteria. For a guide to colors and symbols, see Key. Movie Stars Location seen (if known) Year Director A A.D. 1363, The End of Chivalry 2 Florida Film Festival 2015 2015 Jake Mahaffy A la Francaise 3 Enzian (Oscar Shorts) 2013 Hazebroucq/Leleu/Boyer/Hsien/Lorton The Aaron Case 3 Enzian (FilmSlam 5/16) 2015 Sarah Peterson Aashpordha (Audacity) FL 2 Enzian (South Asian FF) 2011 Anirban Roy Abandoned Love 2 Enzian (Brouhaha 2014) 2014 Sarah Allsup ABC FL 1 Florida Film Festival 2014 2014 Nanna Huolman Abnie Oberfork: A Tale of Self-Preservation 0 Florida Film Festival 2018 2017 Shannon Fleming Abortion Helpline, This Is Lisa 3 Florida Film Festival 2020 2019 Barbara Attie/Janet Goldwater/Mike Attie Abiogenesis 2 Enzian (Oscar Shorts) 2012 Richard Mans The Absence of Eddy Table 4 Florida Film Festival 2017 2016 Rune Spaans Acabo de Tener un Sueño (I’ve Just Had a Dream) FL 3 Love Your Shorts 2016 2014 Javi Navarro Accidents, Blunders and Calamities 1 Florida Film Festival 2016 2015 James Cunningham Accordion Player Sl 1 1888 Louis Le Prince The Accountant 0 Enzian (FilmSlam 10/15) 2015 Stephen Morgan/Alex Couch Achoo 2 Oscar Shorts 2018 2018 L. Boutrot/E. Carret/M. Creantor Acide FL 2 Orlando International FF 2020 2018 Just Philippot Acoustic Ninja 2 Enzian (Brouhaha 2016) 2016 Robert Bevis Ace in the Hole 0 Orlando Film Festival 2013 2013 Wesley T. -

28Th Leeds International Film Festival Presents Leeds Free Cinema Week Experience Cinema in New Ways for Free at Liff 28 from 7 - 13 November

LIFF28th 28 Leeds International Film Festival CONGRATULATIONS TO THE LEEDS INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL IN YOUR 28TH YEAR The BFI is proud to partner with Screen Yorkshire in a fantastic year for filmmaking in the region INCLUDING ‘71 GET SANTA SCREENING AT LIFF28 X + Y CATCH ME DADDY & LIFF28 OPENING NIGHT FILM TESTAMENT OF YOUTH Image: (2014) Testament of Youth James Kent Dir. bfi.org.uk/FilmFund Film Fund Ad LIFF 210x260 2014-10_FINAL 3.indd 1 27/10/2014 11:06 WELCOME From its beginnings at the wonderful, century-old Hyde Park Leeds International Film Festival is a celebration of both Picture House to its status now as a major national film event, film culture and Leeds itself, with this year more than 250 CONGRATULATIONS Leeds International Film Festival has always aimed to bring screenings, events and exhibitions hosted in 16 unique a unique and outstanding selection of global film culture locations across the city. Our venues for LIFF28 include the TO THE LEEDS INTERNATIONAL to the city for everyone to experience. This achievement main hub of Leeds Town Hall, the historic cinemas Hyde is not possible without collaborations and this year we’ve Park Picture House and Cottage Road, other city landmarks FILM FESTIVAL IN YOUR 28TH YEAR assembled our largest ever line-up of partners. From our like City Varieties, The Tetley, Left Bank, and Royal Armouries, long-term major funders the European Union and the British Vue Cinemas at The Light and the Everyman Leeds, in their Film Institute to exciting new additions among our supporting recently-completed Screen 4, and Chapel FM, the new arts The BFI is proud to partner with Screen Yorkshire organisations, including Game Republic, Infiniti, and Trinity centre for East Leeds. -

Film As a Pedagogical Tool for the Teaching and Learning of Social Justice- Orientated Citizenship Education

Lights, Camera, Civic Action! Film as a pedagogical tool for the teaching and learning of social justice- orientated citizenship education. Daryn Bevan Egan-Simon A thesis submitted to the Department of Education, Edge Hill University, in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. July 2020 Abstract Citizenship education in England is largely based on a deficit model of young people that positions them as compliant economic subjects rather than active agents of change (Olser and Starkey, 2003; Kisby, 2017; Weinberg and Flinders, 2018). Furthermore, provision for citizenship education has been described as inadequate, ineffective, sterile and lacking in pedagogical innovation (Turner, 2009; Garratt and Piper, 2012; Kerr et al., 2010). This study addresses the question: how can short animated film be used as a pedagogical tool for the teaching and learning of social justice-orientated citizenship education? Within the study, social justice-orientated citizenship education is conceptualised within a framework consisting of four constitutive elements: agency; dialogue; criticality; and emancipatory/ transformative knowledge. As part of the enquiry, a film-based social justice-orientated citizenship education programme (Lights, Camera, Civic Action!) was designed and organically developed with twelve Year 5 children during the Spring, Summer and Autumn Terms of 2018. An intrinsic case study (Stake, 1995; 2005) was employed as the strategy of enquiry with the preferred qualitative methods of data collection being focus group interviews, participant observations and the visual and technical documents created by the children. Thematic Analysis was used as the analytical method for identifying and reporting themes found through the codification of data sets (Braun and Clarke, 2006; Castlebury and Nolen, 2018). -

Wellington Programme

WELLINGTON 24 JULY – 9 AUGUST BOOK AT NZIFF.CO.NZ 44TH WELLINGTON FILM FESTIVAL 2015 Presented by New Zealand Film Festival Trust under the distinguished patronage of His Excellency Lieutenant General The Right Honourable Sir Jerry Mateparae, GNZM, QSO, Governor-General of New Zealand EMBASSY THEATRE PARAMOUNT SOUNDINGS THEATRE, TE PAPA PENTHOUSE CINEMA ROXY CINEMA LIGHT HOUSE PETONE WWW.NZIFF.CO.NZ NGĀ TAONGA SOUND & VISION CITY GALLERY Director: Bill Gosden General Manager: Sharon Byrne Assistant to General Manager: Lisa Bomash Festival Manager: Jenna Udy Publicist (Wellington & Regions): Megan Duffy PROUDLY SUPPORTED BY Publicist (National): Liv Young Programmer: Sandra Reid Assistant Programmer: Michael McDonnell Animation Programmer: Malcolm Turner Children’s Programmer: Nic Marshall Incredibly Strange Programmer: Anthony Timpson Content Manager: Hayden Ellis Materials and Content Assistant: Tom Ainge-Roy Festival Accounts: Alan Collins Publications Manager: Sibilla Paparatti Audience Development Coordinator: Angela Murphy Online Content Coordinator: Kailey Carruthers Guest and Administration Coordinator: Rachael Deller-Pincott Festival Interns: Cianna Canning, Poppy Granger Technical Adviser: Ian Freer Ticketing Supervisor: Amanda Newth Film Handler: Peter Tonks Publication Production: Greg Simpson Publication Design: Ocean Design Group Cover Design: Matt Bluett Cover Illustration: Blair Sayer Animated Title: Anthony Hore (designer), Aaron Hilton (animator), Tim Prebble (sound), Catherine Fitzgerald (producer) THE NEW ZEALAND FILM -

The Energy Department Wants to Dam Your Favorite River

conservation • access • events • adventure • Safety BY BOATERS FOR BOATERS July/Aug 2014 THE ENERGY DEPARTMENT WANTS TO DAM YOUR FAVORITE RIVER Protecting Headwater StreamS – THE WOTUS RULE AND THE CLEAN WATER Act History AW’s early Stewardship work getting cool on the grand canyon First descent of the middle San Joaquin Where will a take you next? WHITEWATER | TOURING | FISHING · JACKSONKAYAK.COM A VOLUNTEER PUBLICATION PROMOTING RIVER CONSERVATION, ACCESS AND SAFETY american whitewater Journal July/aug 2014 – Volume 54 – issue 4 COLUMNS 5 The Journey Ahead by mark Singleton 30 News & Notes 50 Letter to the Editor 50 Book Review StEWARDSHIP 6 What’s a WOTUS Anyway? Bringing Clarity to the Clean Water Act by megan Hooker 8 The Energy Department Wants to Dam Every River!!? by megan Hooker FEATURE ARTICLES HISTORY 12 Ammo to Use in Fighting for California’s Wild Rivers by Steve LaPrade 15 Another First on the Moose by Pete Skinner 18 “Becuss uf You, Heinrich”by chris Koll 27 First Descent of the Middle Fork San Joaquin by reg Lake INTERNATIONAL 31 Maya Mayhem by Larry rice ROAD TRIPS 42 A Month of Bliss by Jordan Vickers Headwaters all around the nation, like this alpine reach of Publication Title: American Whitewater the Middle Fork San Joaquin (CA), could be ensured Clean Issue Date: July/Aug 2014 Statement of Frequency: Published Bimonthly Water Act protections if a new rule by the EPA and Army Authorized Organization’s Name and Address: American Whitewater Corps of Engineers is implemented. If it’s not, the question P.O. Box 1540 of what qualifies as a WOTUS might remain murky for Cullowhee, NC 28723 years or even generations (see pg. -

Red Bank Register Volume Lxxi, No

RED BANK REGISTER VOLUME LXXI, NO. 2. RED BANK, N. J., THURSDAY, JULY 8, 1948 SECTION ONE—PAGES 1 TO 16 Shrewsbury Council P.U.C Approves Mrs. Thompson Forms Planning Board Firemen's Fair Military, Civil A planning board was formed In County Delays Bus Rdte Rise On Official Staff Shrewsbury Tuesday night. Headed At Hazlet Starts by Mayor Alfred N. Bcadleston and Dig down for the extra two cents, Councilman Herbert Schlld, th« friend. Tho Public Utilities com- Of Riverview group also consists of Irving Reist, Tomorrow Night mission Friday granted a two-cent John H. Hawkins and Arthur School Proposal Tests OK Ocean fare increase to the Boro Bus Co. Moore. of Red Bank and the Coast Cities Accepts Responsibility The board, appointed by the ma- To Award Merchandise Coaches, Inc. yor according to state statute, last Monmouth Officer, However, Blame* The new rates went into effect As Technical Advisor night was sworji into odice. They And Cueh Prizes Merit Of Vocational Program Sunday. The Boro bus routes prev- also held their organization meet- iously five cent* are now seven At Local Hospital ing and discussed work which will Valued At $1,000 State For Inadequate Water Te»U cents, while the ten-cent routes are make up their first year of activity. Praised, But Cost Needs Study now 12 cents. Fifteen-cent rides re- Mrs. Lewis S. Thompson of Announcement of their plans will The 1948 edition of the Hazlet C»pt. Homer E. Carney, medical main the Bame. Brookdale Farm, Lincroft, is now be made at the August 3 meeting Firemen's Fair commences tomor- After one year of Intense study, inspector of Fort Monmouth, has The routes affected are Red Bank- technical advisor at Riverview hos- of the mayor and council, row night and with the exception which included on-the-spot survey! criticized the system of seasonal Long Branch via Eatontown, Red pital. -

Curriculum Map – Ware Public Schools – English Language Arts: Kindergarten

Preliminary Edition – August 2012 Curriculum Map – Ware Public Schools – English Language Arts: Kindergarten A Colorful Time with Rhythm and Rhyme Unit 1 - Number of Weeks: 6 – Sep.-mid Oct. Essential Question: How does rhyme affect the way that we hear and read poetry? Terminology: artist, author, description, illustration, illustrator, informational book, line, opinion, poem, poet, poetry, rhyme, rhythm, stanza, story book, verse Focus Standards Suggested Works/Resources Sample Activities and Assessment Lexile Framework for (E) indicates a CCSS exemplar text (AD) Adult Directed Reading (EA) indicates a text from a writer with other works (IG) Illustrated Guide http://lexile.com/fab/ identified as exemplar (NC) Non-Conforming RI.K.4: With prompting LITERARY TEXTS DIBELS and support, ask and Picture Books (Read Aloud) DRAS answer questions about Red, Green, Blue: A First Book of Colors unknown words in a text. (Alison Jay) POETRY/PRINT CONCEPTS Colors! Colores! (Jorge Lujan and Piet As students read a rhyme, ask them to focus on RL.K.5: Recognize Grobler) listening for rhyming words and hearing the common types of texts Brown Bear, Brown Bear (Bill Martin Jr. and rhythm of the lines. By using musical recordings (e.g., storybooks, poems) Eric Carle) of the nursery rhymes, students can move to the . If Kisses Were Colors (Janet Lawler and rhythm of the rhymes in song and recite the RF.K.2: Demonstrate Alison Jay) words with ease. (RF.K.1, RF.K.3c) understanding of spoken My Many Colored Days (Dr. Seuss) (EA) words, syllables, and Mary Wore Her Red Dress (Merle Peek) POETRY/PHONOLOGICAL AWARENESS phonemes.