The University of Alaska: How Is It Doing? by Theodore L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UAA Assembly Agenda September 12, 2013 1:00 - 3:30 P.M

UAA Assembly Agenda September 12, 2013 1:00 - 3:30 p.m. ADM 204 I. Call to Order II. Introduction of Members P= Present E= Excused President – Liz Winfree Vice President – APT Classified Faculty USUAA Alumni Association Christine Lidren Kathleen McCoy Mark Fitch Andrew Lemish James R. Hemsath (ex-officio) Betty Hernandez Rebecca Huerta Diane Hirshberg Melodee Monson Liz Winfree Tara Smith Dana Sample Kathy Smith Dianne Tarrant Bill Howell Maureen Hunt Lori Hart III. Approval of Agenda (pg. 1) IV. Approval of Summary (pg. 2-3) V. President’s Report VI. Administrative Reports A. Chancellor Case (pg. 4-9) Case Notes http://greenandgold.uaa.alaska.edu/chancellor/casenotes/ FAQ http://www.uaa.alaska.edu/chancellor/ B. Provost & Executive Vice Chancellor Baker C. Vice Chancellor of Administrative Services Spindle D. Vice Chancellor of Advancement Olson (pg. 10-11) E. Vice Chancellor for Student Services Schultz (pg. 12-16) VII. Governance Reports A. System Governance Council B. Staff Alliance C. Classified Council D. APT Council E. Union of Students/ Coalition of Students F. Alumni Association - James R. Hemsath G. Faculty Senate/ Faculty Alliance (pg. 17) VIII. Old Business IX. New Business A. Election: Assembly Vice President B. Student Satisfaction Survey Presentation, Susan Kalina (pg. 18) C. CAS Restructuring Discussion, Patricia Linton D. Assembly Meeting Time Discussion X. Information/Attachments A. Upcoming Governance Events (recurring item) B. Questions for President Gamble email [email protected] XI. Adjourn 1 UAA Assembly Summary May 9, 2013 1:00 - 3:30 p.m. ADM 204 Access Number: 1-800-893-8850 Meeting Number: 7730925 I. -

2013 - 2014 Academic Catalog

2013 - 2014 Academic Catalog Matanuska-Susitna College University of Alaska Anchorage P.O. Box 2889 | Palmer, Alaska 99645 Telephone: 907-745-9774 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.matsu.alaska.edu About this Catalog. This catalog offers you a complete guide to studying at Matanuska-Susitna College (MSC). It includes information on admission and graduation requirements as well as program and course listings for certificate and associate’s degree students. You should refer to this catalog for clarification on what is required of you as a Mat-Su College student and for specific information about what is offered at MSC. If you are a current or enrolling student, you should also refer to the Course Schedule which lists the dates, times and locations of available courses for each semester. Schedules are available a few weeks before registration begins for the upcoming semester. If you need more information, refer to the directory on page 4 for a list of MSC offices and phone numbers. It is the responsibility of the individual student to become familiar with the policies and regulations of MSC/UAA printed in this catalog. The responsibility for meeting all graduation requirements rests with the student. Every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in this catalog. However, the Matanuska-Susitna College catalog is not a contract but rather a guide for the convenience of students. The college reserves the right to change or withdraw courses; to change the fees, rules, and calendar for admission, registration, instruction, and graduation; and to change other regulations affecting the student body at any time. -

The University of Alaska: How Is It Doing?

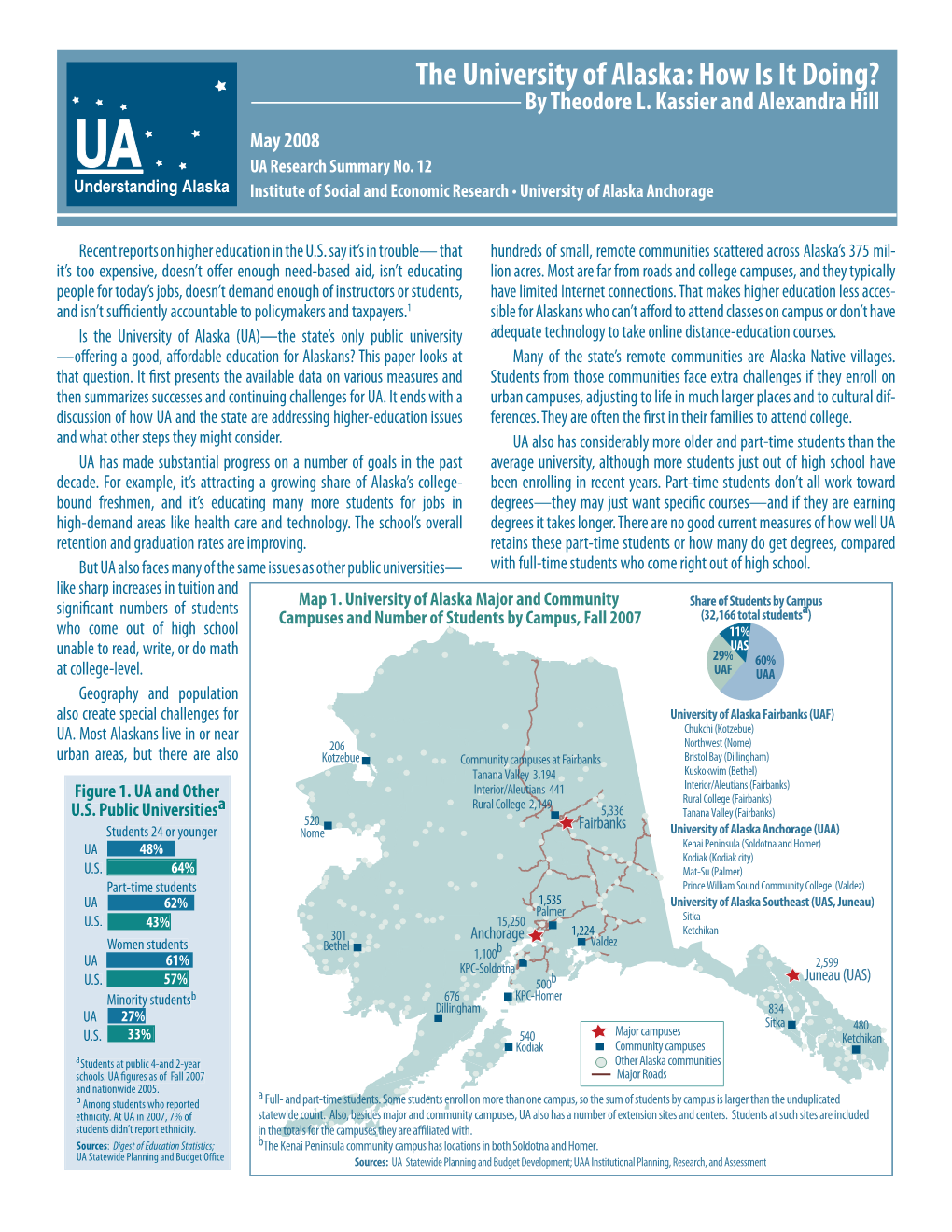

The University of Alaska: How Is It Doing? Item Type Report Authors Kassier, Theodore; Hill, Alexandra Publisher Institute of Social and Economic Research, University of Alaska Anchorage Download date 30/09/2021 15:50:40 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/4428 The University of Alaska: How Is It Doing? By Theodore L. Kassier and Alexandra Hill May 2008 UA Research Summary No. 12 Institute of Social and Economic Research • University of Alaska Anchorage Recent reports on higher education in the U.S. say it’s in trouble— that hundreds of small, remote communities scattered across Alaska’s 375 mil- it’s too expensive, doesn’t offer enough need-based aid, isn’t educating lion acres. Most are far from roads and college campuses, and they typically people for today’s jobs, doesn’t demand enough of instructors or students, have limited Internet connections. That makes higher education less acces- and isn’t sufficiently accountable topolicymakers and taxpayers.1 sible for Alaskans who can’t afford to attend classes on campus or don’t have Is the University of Alaska (UA)—the state’s only public university adequate technology to take online distance-education courses. —offering a good, affordable education for Alaskans? This paper looks at Many of the state’s remote communities are Alaska Native villages. that question. It first presents the available data on various measures and Students from those communities face extra challenges if they enroll on then summarizes successes and continuing challenges for UA. It ends with a urban campuses, adjusting to life in much larger places and to cultural dif- discussion of how UA and the state are addressing higher-education issues ferences. -

State of Alaska FY2021 Governor's Operating Budget

University of Alaska State of Alaska FY2021 Governor’s Operating Budget University of Alaska FY2021 Governor Released December 30, 2019 University of Alaska Page 1 FY2021 Governor Table of Contents University of Alaska 3 Budget Reductions/Additions - Systemwide 19 RDU: Statewide Services 24 Statewide Services 32 Office of Information Technology 46 RDU: University of Alaska Anchorage 55 Anchorage Campus 69 Small Business Development Center 125 RDU: University of Alaska Fairbanks 131 Fairbanks Campus 152 Fairbanks Organized Research 200 RDU: Enterprise Entities 227 University of Alaska Foundation 233 Education Trust of Alaska 240 RDU: University of Alaska Anchorage CC 246 Kenai Peninsula College 250 Kodiak College 262 Matanuska-Susitna College 272 Prince William Sound College 282 RDU: University of Alaska Fairbanks CC 292 Bristol Bay Campus 296 Chukchi Campus 304 College of Rural and Community Development 311 Interior Alaska Campus 319 Kuskokwim Campus 328 Northwest Campus 337 UAF Community and Technical College 345 RDU: University of Alaska Southeast 355 Juneau Campus 364 Ketchikan Campus 379 Sitka Campus 388 Page 2 Released December 30, 2019 University of Alaska University of Alaska Mission University of Alaska System (UA) The University of Alaska inspires learning, and advances and disseminates knowledge through teaching, research, and public service, emphasizing the North and its diverse peoples. AS 14.40.010, AS 14.40.060 Core Services UGF DGF Other Fed Total PFT PPT NP % GF (in priority order) 1 Student Instruction 258,522.6 263,650.9 58,099.6 40,286.4 620,559.5 2,932.0 140.3 0.0 82.4% 2 Research: Advancing Knowledge, 26,917.1 45,644.5 16,936.4 82,242.4 171,740.3 765.6 32.6 0.0 11.4% Basic and Applied 3 Service: Sharing Knowledge to 16,593.8 22,528.8 7,563.5 17,697.1 64,383.2 296.4 16.1 0.0 6.2% Address Community Needs FY2020 Management Plan 302,033.5 331,824.1 82,599.5 140,225.9 856,683.0 3,994.0 189.0 0.0 Measures by Core Service (Additional performance information is available on the web at https://omb.alaska.gov/results.) 1. -

Advancing Civic Learning in Alaska's Schools

Advancing Civic Learning in Alaska’s Schools Final Report of the Alaska Civic Learning Assessment Project November 2006 Special Thanks to the Alaska Civic Learning Assessment Project Advisory Board: DANA FABE Chief Justice, Alaska Supreme Court; ATJN Co-Chair BARBARA JONES Chair, Alaska Bar Assn LRE Committee; ATJN Co-Chair SUELLEN APPELLOF Past President, Alaska PTA MARY BRISTOL We the People – The Citizen & the Constitution SENATOR CON BUNDE Alaska State Legislature MORGAN CHRISTEN Judge, Alaska Superior Court REPRESENTATIVE JOHN COGHILL Alaska State Legislature PAM COLLINS We the People – Project Citizen ESTHER COX Alaska State Board of Education & Early Development JOHN DAVIS Alaska Council of School Administrators SUE GULLUFSEN Alaska Legislative Affairs Agency ELIZABETH JAMES 49th State Fellows Program, UAA DENISE MORRIS Alaska Native Justice Center PAUL ONGTOOGUK College of Education, UAA DEBORAH O’REGAN Executive Director, Alaska Bar Association PAUL PRUSSING Alaska Dept. of Education & Early Development MACON ROBERTS Anchorage School Board KRISTA SCULLY Pro Bono Coordinator, Alaska Bar Association LAWRENCE TROSTLE Justice Center, UAA The Alaska Civic Learning Assessment Project was made possible by a grant to the Alaska Teaching Justice Network (ATJN) from the national Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools. The ATJN is an initiative of the Alaska Court System and the Alaska Bar Association’s LRE Committee, with support from Youth for Justice, a program of the Office of Juvenile Justice & Delinquency Prevention, U.S. Department of Justice. For more information about the ATJN, please contact Bar- bara Hood, Coordinator, at 907-264-0879 or [email protected]. The recommendations in this report will be car- ried forward by Alaska’s delegation to the U.S. -

University of Alaska

University of Alaska Schedule of Travel for Executive Positions Calendar Year 2017 Name: THOMAS CASE Position: Chancellor Organization: University of Alaska Anchorage Dates Traveled Begin End Purpose of Trip Destination Travel Total 1/30/17 1/31/17 Meet with Ahtna board; meet with city officials; meet with Valdez 605 community members; meet with Prince William Sound College faculty, staff and students 2/1/17 2/3/17 Participate in Title IX Crisis Communication training Fairbanks 749 3/14/17 3/15/17 Meet with University of Alaska Anchorage donor; attend student Seattle 472 presentation 5/12/17 5/13/17 Speak at Kodiak College commencement Kodiak 389 5/15/17 5/16/17 Attend Great Northwest Athletic Conference chief executive officer Portland, OR 793 meeting 5/18/17 Attend University of Alaska board of trustees meeting Fairbanks 230 6/1/17 6/2/17 Attend University of Alaska board of regents meeting Fairbanks 744 TOTAL: THOMAS CASE 3,982 Schedule of Travel for Executive Positions Calendar Year 2017 Name: RICHARD CAULFIELD Position: Chancellor Organization: University of Alaska Southeast Dates Traveled Begin End Purpose of Trip Destination Travel Total 1/9/17 Participate in University of Alaska (UA) summit team meeting Anchorage 676 1/12/17 Participate in University of Alaska Southeast (UAS) Sitka Campus Sitka 563 advisory council meeting; conduct UAS Sitka Campus visit 1/17/17 1/20/17 Participate in University of Alaska (UA) board of regents (BOR) Anchorage 959 meeting; participate in UA summit team meeting 1/30/17 2/3/17 Attend Title IX Crisis Communication training; participate in Fairbanks; Anchorage 1,619 University of Alaska Anchorage (UAA) College of Education transition meeting; participate in UA summit team meeting 3/1/17 3/3/17 Participate in UA BOR meeting Anchorage 807 3/10/17 Conduct Alaska College of Education (AKCOE) steering committee Anchorage 571 meeting 3/14/17 3/18/17 Attend American Association of State Colleges and Universities Washington, D.C. -

Do Alaska Native People Get “Free” Medical Care?...78

DO ALASKA NATIVE PEOPLE GET FREE MEDICAL CARE?* And other frequently asked questions about Alaska Native issues and cultures *No, they paid in advance. Read more inside. UNIVERSITY OF ALASKA ANCHORAGE/ALASKA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY Holikachuk Unangax (Aleut) Han Inupiaq Alutiiq Tanacross Athabascan Haida (Lower) Tanana Siberian Yupik / St. Lawrence Island Upper Tanana Tsimshian Tlingit Yupik Deg Xinag (Deg Hit’an) Ahtna Central Yup’ik Koyukon Dena’ina (Tanaina) Eyak Gwich'in Upper Kuskokwim DO ALASKA NATIVE PEOPLE GET FREE MEDICAL CARE?* And other frequently asked questions about Alaska Native issues and cultures *No, they traded land for it. See page 78. Libby Roderick, Editor UNIVERSITY OF ALASKA ANCHORAGE/ALASKA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY 2008-09 BOOKS OF THE YEAR COMPANION READER Copyright © 2008 by the University of Alaska Anchorage and Alaska Pacific University Published by: University of Alaska Anchorage Fran Ulmer, Chancellor 3211 Providence Drive Anchorage, AK 99508 Alaska Pacific University Douglas North, President 4101 University Drive Anchorage, AK 99508 Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the editors, contributors, and publishers have made their best efforts in preparing this volume, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents. This book is intended as a basic introduction to some very complicated and highly charged questions. Many of the topics are controversial, and all views may not be represented. Interested readers are encouraged to access supplemental readings for a more complete picture. This project is supported in part by a grant from the Alaska Humanities Forum and the National Endowment for the Humanities, a federal agency. -

2010 Annual Report University of Alaska Foundation Over 5,300 Alumni, Staff, Faculty, Parents and Friends Supported the University of Alaska This Year

Seeds of Promise 2010 Annual Report University of Alaska Foundation Over 5,300 alumni, staff, faculty, parents and friends supported the University of Alaska this year. The University of Alaska Foundation seeks, secures and stewards philanthropic support to build excellence at the University of Alaska. 2 UNIVERSITY OF ALASKA FOUNDATION FY10 ANNUAL REPORT University of Alaska Foundation FY10 Annual Report Table of Contents Foundation Leaders 4-5 2010 Bullock Prize for Excellence 6-7 Lifetime Giving Recognition 8-9 Legacy Society 10-11 Endowment Administration 12-13 Celebrating Support 14-22 Many Ways to Give 23-24 Tax Credit Changes 25 Scholarships 26-41 Honor Roll of Donors 42-67 Financial Statements 68-88 Donor Bill of Rights 89 UNIVERSITY OF ALASKA FOUNDATION FY10 ANNUAL REPORT 3 FY10 Foundation Leaders Board of Trustees Executive Committee Finance and Audit Committee Sharon Gagnon, Chair (6/09 –11/09) Sharon Gagnon, Chair Ann Parrish, Chair Mike Felix, Vice Chair (6/09 –11/09) Mike Felix, Chair Cheryl Frasca, Vice Chair Mike Felix, Chair (11/09–6/10) Jo Michalski Will Anderson Jo Michalski, Vice Chair (11/09–6/10) Carla Beam Laraine Derr Carla Beam, Secretary Mark Hamilton Darren Franz Susan Anderson Ann Parrish Garry Hutchison Will Anderson Mary Rutherford, Ex-officio Wendy King Alison Browne Bob Mitchell Leo Bustad Committee on Trusteeship Melody Schneider Angela Cox Alison Browne, Chair Sharon Gagnon, Ex-officio Ted Fathauer Mary K. Hughes Mike Felix, Ex-officio Patrick Gamble Ann Parrish Mary Rutherford, Ex-officio Greg Gursey Arliss Sturgulewski Mark Hamilton Carolyne Wallace Investment Committee Mary K. -

Course Descriptions

COURSE DESCRIPTIONS 13 Course Descriptions 13 CourseCourse Descriptions Descrip ACCT A210 Income Tax Preparation 3 CR ACCT - Accounting Contact Hours: 3 + 0 Offered through the College of Business & Public Policy Prerequisites: [ACCT A101 and ACCT A102] or ACCT A201 and CIS A110. Edward & Cathryn Rasmuson Hall (RH), Room 203, 786-4100 Preparation of individual income tax returns, manually and computerized (using the latest in tax preparation software). Tax research and tax planning with www.cbpp.uaa.alaska.edu emphasis on primary and administrative sources of income tax law. Emphasis is Students taking any ACCT, BA, CIS, ECON, LGOP, LOG, or PADM course will be on the sources and interpretation of the tax laws and principles as well as how they charged a single lab fee of $25 for the semester. Applies to Elmendorf Air Force apply to individuals. Base or Fort Richardson classes only when specifically noted on UAOnline. Does not apply to Chugiak-Eagle River classes. ACCT A216 Accounting Information Systems I 3 CR Contact Hours: 3 + 0 ACCT A051 Recordkeeping for Small Business 1 CR Prerequisites: [ACCT A101 with minimum grade of C and ACCT A102 with Contact Hours: 1 + 0 minimum grade of C] or ACCT A201 with minimum grade of C. Offered only at Matanuska-Susitna College. Studies the role and importance of the Accounting Information System (AIS) Special Note: Does not satisfy any degree requirements even as an elective. within an organization, including an in-depth examination of the accounting cycle Provides an overview of what bookkeepers do and the role they provide to a from transaction initiation through financial statement preparation and analysis. -

Proposed FY2018 Capital Budget and 10-Year Capital Improvement Plan

Proposed FY2018 Capital Budget and 10-Year Capital Improvement Plan Board of Regents November 10-11, 2016 Fairbanks, Alaska Prepared by: University of Alaska Statewide Office of Planning and Budget 907.450.8191 http://www.alaska.edu/swbir/ Table of Contents Proposed FY2018 Capital Budget Request Introduction ..........................................................................................................................1 Proposed FY2018 Capital Budget Request..........................................................................2 Proposed 10-Year Capital Improvement Plan .....................................................................3 FY2018 Capital Budget Request Project Descriptions ........................................................6 FY2018 Priority Deferred Maintenance (DM) and Renewal & Repurposing (R&R) Projects .........................................................................25 FY2018 Priority Deferred Maintenance (DM) and Renewal & Repurposing (R&R) Project Descriptions .....................................................26 References FY2018 Deferred Maintenance (DM) and Renewal & Repurposing (R&R) Distribution Methodology ...........................................................32 Capital Budget Request vs. State Appropriation ...............................................................33 Capital Request and Appropriation Summary (chart) .......................................................34 State Appropriation Summary by Category and MAU ......................................................35 -

FY13 Enacted Legislative Intent

Michelle Rizk, Associate Vice President Budget (907) 450-8187 PO BOX 755260 (907) 450-8181 fax 910 Yukon Drive Ste. 108 [email protected] Fairbanks, AK 99775-5260 November 28, 2012 Amanda Ryder Senior Fiscal Analyst/Operating Budget Alaska Legislative Finance Division P.O. Box 113200 Juneau, AK 99811-3200 Dear Ms. Ryder: Included below is the University of Alaska’s actions in regard to the FY13 enacted legislative intent. UNIVERSITY OF ALASKA Operating Budget (CCS HB 284) It is the intent of the legislature that the University of Alaska submits a FY14 budget in which requests for unrestricted general fund increments do not exceed the amount of additional University Receipts requested for that year. It is the intent of the legislature that future budget requests of the University of Alaska for unrestricted general funds move toward a long-term goal of 125 percent of actual University Receipts for the most recently closed fiscal year. The University of Alaska believes the purpose of the intent language was to 1) stabilize the general fund level; 2) incent generation of non-general fund revenue; and 3) inform Regents of the true budget constraints that will exist in the future as they negotiate salaries and enter into other financial commitments. The University of Alaska's FY14 budget request reflects the legislature's intent. The budget request for the University of Alaska exercises tight spending discipline while limiting growth, and yet preserving and when necessary, investing in essential infrastructure. UA’s comprehensive plan for materially improving higher education in Alaska began in FY13, with the Strategic Direction Initiative (SDI). -

UAA Assembly Agenda April 11, 2013 1:00 - 3:30 P.M

UAA Assembly Agenda April 11, 2013 1:00 - 3:30 p.m. RH 303 Access Number: 1-800-893-8850 Meeting Number: 7730925 I. Call to Order II. Introduction of Members P= Present E= Excused President – Debbie Narang Vice President – Kathy Smith APT Classified Faculty USUAA Alumni Association Melodee Monson Connie Dennis Robert Boeckmann Alejandra Buitrago James R. Hemsath (ex-officio) Dana Sample Kathleen McCoy Mark Fitch Andrew Lessig Carey Brown Sarah Pace Tara Smith Max Bullock Betty Hernandez Tamah Hayes Peter Snow Glenna Muncy Deborah Narang III. Approval of Agenda (pg. 1) IV. Approval of Summary (pg. 2-3) V. President’s Report VI. Administrative Reports A. Chancellor Case (pg. 4-12) FAQ http://www.uaa.alaska.edu/chancellor/ B. Provost & Executive Vice Chancellor Baker C. Vice Chancellor of Administrative Services Spindle D. Vice Chancellor of Advancement Olson E. Vice Chancellor for Student Services Schultz (pg. 13-16) VII. Governance Reports A. System Governance Council B. Staff Alliance C. Classified Council D. APT Council E. Union of Students/ Coalition of Students F. Alumni Association - James R. Hemsath G. Faculty Senate/ Faculty Alliance VIII. Old Business IX. New Business A. National Coalition Building Institute (NCBI) Training X. Information/Attachments A. Upcoming Governance Events (recurring item) XI. Adjourn 1 UAA Assembly Summary March 7, 2013 1:00 - 3:30 p.m. ADM 204 Access Number: 1-800-893-8850 Meeting Number: 7730925 I. Call to Order II. Introduction of Members P= Present E= Excused x President – Debbie Narang x Vice President – Kathy Smith APT Classified Faculty USUAA Alumni Association X Melodee Monson X Connie Dennis e Robert Boeckmann Alejandra Buitrago James R.