A Digital Copy of the Exhibit Catalog

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogue of the Famous Blackborne Museum Collection of Laces

'hladchorvS' The Famous Blackbome Collection The American Art Galleries Madison Square South New York j J ( o # I -legislation. BLACKB ORNE LA CE SALE. Metropolitan Museum Anxious to Acquire Rare Collection. ' The sale of laces by order of Vitail Benguiat at the American Art Galleries began j-esterday afternoon with low prices ranging from .$2 up. The sale will be continued to-day and to-morrow, when the famous Blackborne collection mil be sold, the entire 600 odd pieces In one lot. This collection, which was be- gun by the father of Arthur Blackborne In IS-W and ^ contmued by the son, shows the course of lace making for over 4(Xi ye^rs. It is valued at from .?40,fX)0 to $oO,0()0. It is a museum collection, and the Metropolitan Art Museum of this city would like to acciuire it, but hasnt the funds available. ' " With the addition of these laces the Metropolitan would probably have the finest collection of laces in the world," said the museum's lace authority, who has been studying the Blackborne laces since the collection opened, yesterday. " and there would be enough of much of it for the Washington and" Boston Mu- seums as well as our own. We have now a collection of lace that is probablv pqual to that of any in the world, "though other museums have better examples of some pieces than we have." Yesterday's sale brought SI. .350. ' ""• « mmov ON FREE VIEW AT THE AMERICAN ART GALLERIES MADISON SQUARE SOUTH, NEW YORK FROM SATURDAY, DECEMBER FIFTH UNTIL THE DATE OF SALE, INCLUSIVE THE FAMOUS ARTHUR BLACKBORNE COLLECTION TO BE SOLD ON THURSDAY, FRIDAY AND SATURDAY AFTERNOONS December 10th, 11th and 12th BEGINNING EACH AFTERNOON AT 2.30 o'CLOCK CATALOGUE OF THE FAMOUS BLACKBORNE Museum Collection of Laces BEAUTIFUL OLD TEXTILES HISTORICAL COSTUMES ANTIQUE JEWELRY AND FANS EXTRAORDINARY REGAL LACES RICH EMBROIDERIES ECCLESIASTICAL VESTMENTS AND OTHER INTERESTING OBJECTS OWNED BY AND TO BE SOLD BY ORDER OF MR. -

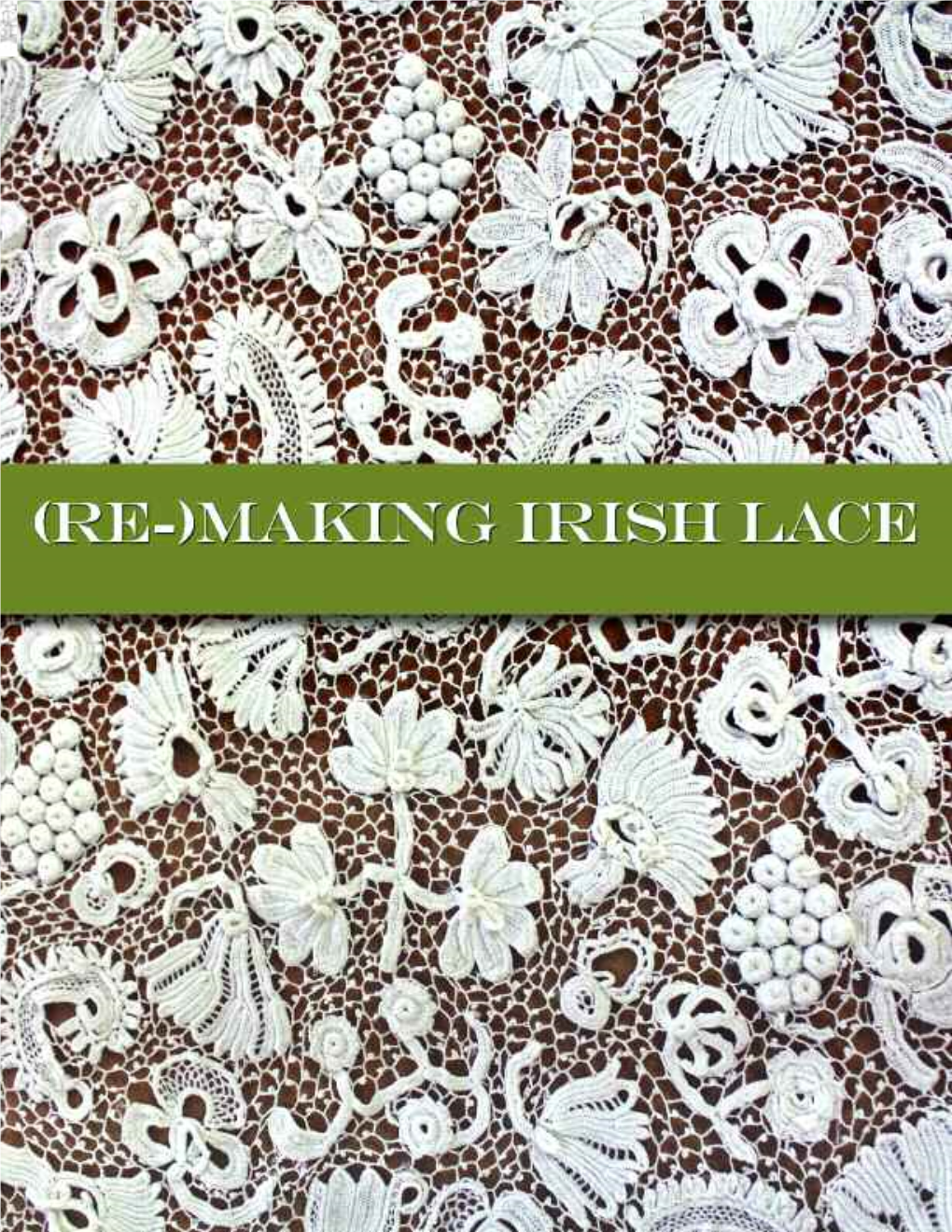

Beautiful Contemporary Interpretations of Lace

Beautiful contemporary interpretations of Irish lace woven together for Interlace exhibition. Absolut Mode by Natalie B Coleman Make Good, Make Better by Saidhbhín Gibson National Craft Gallery, Kilkenny: 28th March – 7th May, 2014 Opening Event: Friday 28th March, 2014 www.nationalcraftgallery.ie "More than a luxury, lace was once central to Irish life, and even to survival. These makers look at lace’s almost magical properties." – Gemma Tipton, Interlace Exhibition Catalogue Interlace takes the history of lace as a starting point and creates a unique exhibition of work by 8 very different women, focusing on their contemporary interpretations of lace. The concept of the show developed and curated by the National Craft Gallery is to explore how traditional material culture creates a resonant source for contemporary practice. This is one of a series of exhibitions to take traditional or vernacular practice as a starting point. Each of the 8 participating artists tells her own individual story through her work and this exhibition offers an insight into how they have been influenced and inspired by our lace heritage to make everything from ravens to a wedding dress, from glass etchings to a celebration of the lace industry in Youghal, Co. Cork. Caroline Schofield Caroline studied textiles in NCAD and embroidery with City & Guilds. Currently working in Kilkenny, this summer she will be doing a residency in Grote Kerk Veere GKV in the Netherlands and showing in “Irish Wave” in Beijing. “In Ireland, lace families survived the famine of 1845/6 due to the foresight of those who introduced lace into their communities and the ability of these women to create beautiful work in very poor conditions.” Caroline Schofield In Greek mythology the God Odin had two ravens, Huginn meaning ‘thought’ and Muninn meaning ‘memory’. -

Lace, Its Origin and History

*fe/m/e/Z. Ge/akrtfarp SSreniano 's 7?ew 2/or/c 1904 Copyrighted, 1904, BY Samuel L. Goldenberg. — Art library "I have here only a nosegay of culled flowers, and have brought nothing of my own but the thread that ties them together." Montaigne. HE task of the author of this work has not been an attempt to brush the dust of ages from the early history of lace in the •^ hope of contributing to the world's store of knowledge on the subject. His purpose, rather, has been to present to those whose rela- tion to lace is primarily a commercial one a compendium that may, perchance, in times of doubt, serve as a practical guide. Though this plan has been adhered to as closely as possible, the history of lace is so interwoven with life's comedies and tragedies, extending back over five centuries, that there must be, here and there in the following pages, a reminiscent tinge of this association. Lace is, in fact, so indelibly associated with the chalets perched high on mountain tops, with little cottages in the valleys of the Appenines and Pyrenees, with sequestered convents in provincial France, with the raiment of men and women whose names loom large in the history of the world, and the futile as well as the successful efforts of inventors to relieve tired eyes and weary fingers, that, no matter how one attempts to treat the subject, it must be colored now and again with the hues of many peoples of many periods. The author, in avowing his purpose to give this work a practical cast, does not wish to be understood as minimizing the importance of any of the standard works compiled by those whose years of study and research among ancient volumes and musty manuscripts in many tongues have been a labor of love. -

The Complete Costume Dictionary

The Complete Costume Dictionary Elizabeth J. Lewandowski The Scarecrow Press, Inc. Lanham • Toronto • Plymouth, UK 2011 Published by Scarecrow Press, Inc. A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 http://www.scarecrowpress.com Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom Copyright © 2011 by Elizabeth J. Lewandowski Unless otherwise noted, all illustrations created by Elizabeth and Dan Lewandowski. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lewandowski, Elizabeth J., 1960– The complete costume dictionary / Elizabeth J. Lewandowski ; illustrations by Dan Lewandowski. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-8108-4004-1 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8108-7785-6 (ebook) 1. Clothing and dress—Dictionaries. I. Title. GT507.L49 2011 391.003—dc22 2010051944 ϱ ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed in the United States of America For Dan. Without him, I would be a lesser person. It is the fate of those who toil at the lower employments of life, to be rather driven by the fear of evil, than attracted by the prospect of good; to be exposed to censure, without hope of praise; to be disgraced by miscarriage or punished for neglect, where success would have been without applause and diligence without reward. -

Th E St Ory Ofir Ish Lace Is a St Ory O

www.nmni.com/uftm/Collections/Textiles---Costume/Lace-page Ulster Folk and Transport Museum, lace collection. collection. lace Museum, Transport and Folk Ulster To find a conservator: www.conservationireland.org conservator: a find To www.museum.ie/en/collection/lace.aspx National Museum of Ireland, Lace collection. collection. Lace Ireland, of Museum National Useful contacts: Useful Vol. 26, No. 2, pp.152-167. 2, No. 26, Vol. Display and Meaning, 1886–1909’ in Journal of Design History 2013, 2013, History Design of Journal in 1886–1909’ Meaning, and Display Embroidery, Dresses: ‘Irish’ Aberdeen’s ‘Ishbel J., Helland, Ireland’, Women’s History Review, 1996, Vol. 5, Issue 3, pp. 326-345. pp. 3, Issue 5, Vol. 1996, Review, History Women’s Ireland’, organisation: Commercial lace embroidery in early 19th-century 19th-century early in embroidery lace Commercial organisation: Chapman S. & Sharpe, P., ‘Women’s employment and industrial industrial and employment ‘Women’s P., Sharpe, & S. Chapman There are a number of articles on Irish lace-making, including: lace-making, Irish on articles of number a are There Further reading: Further www.oidfa.com www.laceguild.org Library of Ireland of Library www.craftscotland.org The Lawrence Photograph Collection, Courtesy of the National National the of Courtesy Collection, Photograph Lawrence The Circular lace photo: lace Circular Irish lace collar (c.1865-1914), Robert French, French, Robert (c.1865-1914), collar lace Irish Other sites relating to lace-making include: lace-making to relating sites Other -

The Dictionary of Needlework

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Boston Library Consortium IVIember Libraries http://www.archive.org/details/dictionaryofneed03caul THE DICTIONARY OF NEEDLEWORK GUIPURE D'ART. macram£ MODERN POINT. DEDICATED TO H.R.H. PRINCESS LOUISE. MARCHIONESS OF LORNE. THE DimiOIlJiW OF I^EEDIiEtflO^I^, ENCYCLOPEDIA OE AETISTIC, PLAIN, AND EANCY NEEDLEWORK, DEALING FULLY WITH THE DETAILS OF ALL THE STITCHES EMPLOYED, THE METHOD OF WOEKING. THE MATERIALS USED, THE MEANING OF TECHNICAL TEEMS, AND, WHERE NECESSARY, TRACING THE ORIGIN AND HISTORY OF THE VARIOUS WORKS DESCRIBED. ILLUSTRATED WITH UPWARDS OF 1200 WOOD ENGRAVINGS, AND COLOURED PLATES. PLAIN SEWING, TEXTILES, DRESSMAKING, APPLIANCES, AND TERMS, By S. E. a. CAULEEILD, Aitthor of "Side Nursiiin at Some," "Desmond," "Avencle," and Papers on Needlework in "TIte Queen," "Girl's Own Paper," "Cassell's Domestic Dictionary," tC-c. CHURCH EMBROIDERY, LACE, AND ORNAMENTAL NEEDLEWORK, By blanche C. SAWAED, AiUhoi- of ''Church Festival Decorations," and Papers on Fancy and Art Work in "The Bazaar," ''Artistic Amusementu," '^Girl's Own Paper," tfcc. Division 1 1 1 .— E m b to K n i . SECOND EDITION. LONDON: A. W. COWAN, 30 AKD 31, NEW BEIDGE STREET. LUDGATE CIRCUS. LONDON: PRINTED BY A. BRADLEY, 170, '^/?.^'?-^Y : THE DICTIONARY OF NEEDLEWORK. 193 and it is sometimes vavied in tlio manuoi- illustrated in of the leaf in rows of large Back Stitches, and pad Fig. 376, where it fills in with int. i-ia.va sdtri,,.; f^i.le the left hand with perpendicular runnings, giving the of the leaf, of -which the other greatest height near the centre is worked in Back Stitch, the veins. -

LACE and LACE MAKING by ESTHER SINGLETON

A Value Not to Be Measured Association is confronted with an unusual situation, and gg riT^^^ B ^y we now appeal to you because you are as vitally interested in a The Mentor as we are. You have often asked—how the full bene- gi fits of The Mentor could be given for tlie price ^beautiful pictures a in gravure and in colors, interesting, instructive text by well-known a writers, and a full, intelligent service in suppljring information in the a various fields of knowledge—all for the annual membership fee of n $3.00.' One of you recently wrote to us: "The Mentor is a bargain for Q the money. This additional service makes it absolutely priceless." a imi JOW have we been able to do it? By care and good judgment, nand by knowing where and how to get things—at a minimum ™ price. But that was under normal conditions. Now new condi- a * tions are forced upon us. Paper, ink, labor, and everything that " goes into the manufacture of magaziiies and books have advanced a " in cost one hundred per cent, or more. The paper on which The o " Mentor is printed cost 4% cents a poimd two years ago. To-day B " it costs 9 cents a pound—and it is still going up. And so it is with ° the cost of other materials. The condition is a general one in the ^ " publishing business. B ' ; ra ; a ^¥S^ have been together in a delightful association for fovir years b ffl \4/ —^just the length of a college course. -

The Lacenews Chanel on Youtube December 2011 Update

The LaceNews Chanel on YouTube December 2011 Update http://www.youtube.com/user/lacenews Bobbinlace Instruction - 1 (A-H) 11Preparing bobbins for lace making achimwasp 10/14/2007 music 22dentelle.mpg AlainB13 10/19/2010 silent 33signet.ogv AlainB13 4/23/2011 silent 44napperon.ogv AlainB13 4/24/2011 silent 55Evolution d'un dessin technique d'une dentelle aux fuseaux AlainB13 6/9/2011 silent 66Galon en dentelle style Cluny AlainB13 11/20/2011 no narration 77il primo videotombolo alikingdogs 9/23/2008 Italian 881 video imparaticcio alikingdogs 11/14/2008 Italian 992 video imparaticcio punto tela alikingdogs 11/20/2008 Italian 10 10 imparaticcio mezzo punto alikingdogs 11/20/2008 Italian 11 11 Bolillos, Anaiencajes Hojas de guipur Blancaflor2776 4/20/2008 Spanish/Catalan 12 12 Bolillos, hojas de guipur Blancaflor2776 4/20/2008 silent 13 13 Bolillos, encaje 3 pares Blancaflor2776 6/26/2009 silent 14 14 Bobbin Lacemaking BobbinLacer 8/6/2008 English 15 15 Preparing Bobbins for Lace making BobbinLacer 8/19/2008 English 16 16 Update on Flower Project BobbinLacer 8/19/2008 English 17 17 Cómo hacer el medio punto - Encaje de bolillos canalsapeando 10/5/2011 Spanish 18 18 Cómo hacer el punto entero o punto de lienzo - Encaje de bolillos canalsapeando 10/5/2011 Spanish 19 19 Conceptos básicos - Encaje de bolillos canalsapeando 10/5/2011 Spanish 20 20 Materiales necesarios - Encaje de bolillos canalsapeando 10/5/2011 Spanish 21 21 Merletto a fuselli - Introduzione storica (I) casacenina 4/19/2011 Italian 22 22 Merletto a Fuselli - Corso: il movimento -

Dressmakers Dictionary

S 1309 >py 1 'r/ce Co/r/^s- \ aOPYRIOMTEB BY J. W. GODDARD Au SONS (incohporatks) • a-S4-»« BLCCCKER ST., NEW YORK Dressmakers Dictionary PRICE TWENTY-FIVE CENTS (^, ^ui'^irvw^xv O Copyrighted, 1916, by J. W. GODDARD & SONS (Incorporated) 92-94-96 BLEECKER ST., NEW YORK Acknowledging the Dress- makers' Chart in the center of this booklet, from the Jno. J. Mitchell Co., Pub- lishers, and valuable assist- ance from the Dry Goods Economist. rs/3o9 SEP 19 1916 ©CI.A437740 Compiled by HOMER S. CURTIS 1916 With Our Compliments ^^^^^HE purpose of this little m C"*\ booklet is not to bore you ^L J with things you already ^^i^^ know, but rather to sup- ply you with information that may prove useful and interesting. A careful perusal cannot fail to aid you in tasteful and harmonious selection of fabrics for your suits and gowns, possibly strengthening your judgment and, perhaps, point- ing the way to more beautiful and finer wardrobes, without an increased expenditure. That you will find it helpful is the wish of the makers of Witchiex Is a Universal Linmg Fabric Terms A List, Giving the Meaning of the Terms in Everyday Use at Dress Goods and Silk Counters. Agra Gauze—Strong, transparent silk fabric of a gauzy texture. ^^ Agaric—^A cotton fabric of loop yam construction, having a surface somewhat similar to a fine Turkish toweling. Armoisine—Also spelled "Armozeen" and "Armo- zine." In the 18th century and earlier this fabric was used in both men's and women's wear. It was of a taffeta or plain silk texture. -

The Lacenews Chanel on Youtube October 2011 Update

The LaceNews Chanel on YouTube October 2011 Update http://www.youtube.com/user/lacenews Bobbinlace Instruction - 1 (A-H) 11Preparing bobbins for lace making achimwasp 10/14/2007 music 22dentelle.mpg AlainB13 10/19/2010 silent 33signet.ogv AlainB13 4/23/2011 silent 44napperon.ogv AlainB13 4/24/2011 silent 55Evolution d'un dessin technique d'une dentelle aux fuseaux AlainB13 6/9/2011 silent 66Galon en dentelle style Cluny AlainB13 11/20/2011 no narration 77il primo videotombolo alikingdogs 9/23/2008 Italian 881 video imparaticcio alikingdogs 11/14/2008 Italian 992 video imparaticcio punto tela alikingdogs 11/20/2008 Italian 10 10 imparaticcio mezzo punto alikingdogs 11/20/2008 Italian 11 11 Bolillos, Anaiencajes Hojas de guipur Blancaflor2776 4/20/2008 Spanish/Catalan 12 12 Bolillos, hojas de guipur Blancaflor2776 4/20/2008 silent 13 13 Bolillos, encaje 3 pares Blancaflor2776 6/26/2009 silent 14 14 Bobbin Lacemaking BobbinLacer 8/6/2008 English 15 15 Preparing Bobbins for Lace making BobbinLacer 8/19/2008 English 16 16 Update on Flower Project BobbinLacer 8/19/2008 English 17 17 Cómo hacer el medio punto - Encaje de bolillos canalsapeando 10/5/2011 Spanish 18 18 Cómo hacer el punto entero o punto de lienzo - Encaje de bolillos canalsapeando 10/5/2011 Spanish 19 19 Conceptos básicos - Encaje de bolillos canalsapeando 10/5/2011 Spanish 20 20 Materiales necesarios - Encaje de bolillos canalsapeando 10/5/2011 Spanish 21 21 Merletto a fuselli - Introduzione storica (I) casacenina 4/19/2011 Italian 22 22 Merletto a Fuselli - Corso: il movimento -

LIBRARY BORROWING, PRIVILAGES and RULES Lace Group Cat No

FOR THE BENEFIT OF ALL MEMBERS Qld Lace Guild Website http://qldlace.org LIBRARY BORROWING, PRIVILAGES AND RULES BORROWING: Request by mail or phone to the Librarian Mr John Lowther, 14 Green Street, LOWOOD, Q 4311 Phone (07) 54262133 after dark or leave message on answering machine Email address - not available Remember to include/leave your name, postal address and ALG Membership Number along with Book Title and catalogue number and/or phone number Three items maximum may be borrowed / on loan at any one time LENDING: The borrower can keep the books for 3 months providing no other member requests them during that time. When requested by another member, the Librarian can recall the book/s, but not before the borrower has had them for a minimum of 1 month. If recalled they should be returned as soon as possible. Videos/DVDs and Newsletters may be borrowed for 1 month only RETURNING: Books and/or Videos/DVDs should be returned in the same packaging as they were sent or another Jiffy pack, cardboard or solid package material to avoid damage. It is the borrower's responsibility to do so as she (he) can be asked to pay replacement cost of book or video. NOTES: There is a $2.00 charge per item borrowed. The borrower pays return postage only. Cost of damage or loss of book/s (video/s, DVD) is met by the borrower. Failure to return items within the due time will result in the member being unable to borrow again. Should you have any queries as to the contents of a book, or where to find particular requirements, re assessment material etc., your librarian is only too happy to help with advice. -

Laces and Lace Articles Laces and Lace Articles 223

222 LACES AND LACE ARTICLES LACES AND LACE ARTICLES 223- TABLE 107.—Rates of wages paid in the domestic and English bobbinet indun ' TABLE 108.—Index of the cost of living fixed by the Regional Commission of the n& for auxiliary processes Prefecture of the Rhone Process Domestic rates English rates i Index Index Date figure figure $0.145 per bundle (10 pounds). 4Kd.=$0. 0862 per bundle (10 pounds'! 30/2 $0.160 per bundle J 5Kd.= . 1115 per bundle. " December 1926. 500 40/2 $0.177 per bundle 6Jid.= . 1267 per bundle. August.1920 461 $0.207 per bundle December 1924. December 1927. 7Kd.= . 1521 per bundle. 379 March 1928 459 80/2 $0,355 per bundle... 10Md.= . 2129 per bundle. December 1925. The average weekly wages for Less 26 percent. this process paid by tbe firms from whom these fig ures were obtained is $21. IX. COST DATA "Warping f$0.85 to $0.90 per hour 15d. per hour = $0.3042. 1. Material costs (.Average per week, $40. Week of 48 hours, £3 = $14.60, less 25 percent Brass-bobbin winding... f$0.26 per 1,000 f All gages, up to and including 125 yards "„ In the manufacture of bobbinets yarns are used for two purposes, \$0.45, $0.50, $0.60 per hour \ 1,000, 6Md.=$0.1369. * aS' ljCr Average per week, $27.25 J4d. extra for every 25 yards or portion the^M for warp and for brass bobbins; the ascertainment of the amount of less 33% percent. each in a wmding does not present any difficulty.