Examining the Relevance of the Theories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uganda Date: 30 October 2008

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: UGA33919 Country: Uganda Date: 30 October 2008 Keywords: Uganda – Uganda People’s Defence Force – Intelligence agencies – Chieftaincy Military Intelligence (CMI) – Politicians This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide information on the Uganda Peoples Defence Force (Ugandan Army)/Intelligence Agencies and a branch of the Army called Chieftaincy Military Intelligence, especially its history, structure, key officers. Please provide any information on the following people: 2. Noble Mayombo (Director of Intelligence). 3. Leo Kyanda (Deputy Director of CMI). 4. General Mugisha Muntu. 5. Jack Sabit. 6. Ben Wacha. 7. Dr Okungu (People’s Redemption Army). 8. Mr Samson Monday. 9. Mr Kyakabale. 10. Deleted. RESPONSE 1. Please provide information on the Uganda Peoples Defence Force (Ugandan Army)/Intelligence Agencies and a branch of the Army called Chieftaincy Military Intelligence, especially its history, structure, key officers. The Uganda Peoples Defence Force UPDF is headed by General Y Museveni and the Commander of the Defence Force is General Aronda Nyakairima; the Deputy Chief of the Defence Forces is Lt General Ivan Koreta and the Joint Chief of staff Brigadier Robert Rusoke. -

Ethnicity and the Politics of Land Tenure: Reform in Central Uganda

Working Paper Series ISSN 1470-2320 2005 No.05-58 Ethnicity and the Politics of Land Tenure Reform in Central Uganda: Elliott D. Green Published: April 2005 Development Studies Institute London School of Economics and Political Science Houghton Street Tel: +44 (020) 7955 7425/6252 London Fax: +44 (020) 7955-6844 WC2A 2AE UK Email: [email protected] Ethnicity and the Politics of Land Tenure Reform in Central Uganda Elliott D. Green1 Development Studies Institute London School of Economics [email protected] 1. Introduction Land tenure reform is certainly one of the most divisive yet important topics in Sub-Saharan Africa today. For countries with high rural populations and high population growth rates, an efficient and fair land tenure system is commonly seen as necessary in order to alleviate poverty and reduce conflict.2 Yet in the central Uganda region of Buganda land tenure has been a heated issue ever since the British created a grossly unequal land tenure system in 1900 that gave large tracts of land to the political elite while turning most Baganda into tenant farmers. While there has been limited success over the past century in limiting the powers of landlords, the system itself has remained. Indeed, Bugandan landlords have been one of the strongest forces in opposition to current attempts at land reform by the ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM), led by President Yoweri Museveni. Recent analyses of land tenure reform in Africa often stop here, limiting discussions to landlords and rural elites on one hand vs. the central government and donors on the other. -

Rule by Law: Discriminatory Legislation and Legitimized Abuses in Uganda

RULE BY LAW DIscRImInAtORy legIslAtIOn AnD legItImIzeD Abuses In ugAnDA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2014 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2014 Index: AFR 59/06/2014 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Ugandan activists demonstrate in Kampala on 26 February 2014 against the Anti-Pornography Act. © Isaac Kasamani amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. Introduction -

Chased Away and Left to Die

Chased Away and Left to Die How a National Security Approach to Uganda’s National Digital ID Has Led to Wholesale Exclusion of Women and Older Persons ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Publication date: June 8, 2021 Cover photo taken by ISER. An elderly woman having her biometric and biographic details captured by Centenary Bank at a distribution point for the Senior Citizens’ Grant in Kayunga District. Consent was obtained to use this image in our report, advocacy, and associated communications material. Copyright © 2021 by the Center for Human Rights and Global Justice, Initiative for Social and Economic Rights, and Unwanted Witness. All rights reserved. Center for Human Rights and Global Justice New York University School of Law Wilf Hall, 139 MacDougal Street New York, New York 10012 United States of America This report does not necessarily reflect the views of NYU School of Law. Initiative for Social and Economic Rights Plot 60 Valley Drive, Ministers Village Ntinda – Kampala Post Box: 73646, Kampala, Uganda Unwanted Witness Plot 41, Gaddafi Road Opp Law Development Centre Clock Tower Post Box: 71314, Kampala, Uganda 2 Chased Away and Left to Die ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report is a joint publication by the Digital Welfare State and Human Rights Project at the Center for Human Rights and Global Justice (CHRGJ) based at NYU School of Law in New York City, United States of America, the Initiative for Social and Economic Rights (ISER) and Unwanted Witness (UW), both based in Kampala, Uganda. The report is based on joint research undertaken between November 2020 and May 2021. Work on the report was made possible thanks to support from Omidyar Network and the Open Society Foundations. -

Militarization in East Africa 2017

Adams Annotated Bibliography on Militarization in East African 1 SSHRC Partnership: Conjugal Slavery in Wartime Masculinities and Femininities Thematic Group Annotated Bibliography on Militarization of East Africa Aislinn Adams, Research Assistant Adams Annotated Bibliography on Militarization in East African 2 Table of Contents Statistics and Military Expenditure ...................................................................................... 7 World Bank. “Military Expenditure (% of GDP).” 1988-2015. ..................................................... 7 Military Budget. “Military Budget in Uganda.” 2001-2012. ........................................................... 7 World Bank. “Expenditure on education as % of total government expenditure (%).” 1999-2012. ........................................................................................................................................................ 7 World Bank. “Health expenditure, public (% of GDP).” 1995-2014. ............................................. 7 World Health Organization. “Uganda.” ......................................................................................... 7 - Total expenditure on health as % if GDP (2014): 7.2% ......................................................... 7 United Nations Development Programme. “Expenditure on health, total (% of GDP).” 2000- 2011. ................................................................................................................................................ 7 UN Data. “Country Profile: Uganda.” -

An Independent Review of the Performance of Special Interest Groups in Parliament

DEEPENING DEMOCRACY AND ENHANCING SUSTAINABLE LIVELIHOODS IN UGANDA DEEPENING DEMOCRACY AND ENHANCING SUSTAINABLE LIVELIHOODS IN UGANDA An Independent Review of the Performance of Special Interest Groups in Parliament Arthur Bainomugisha Elijah D. Mushemeza ACODE Policy Research Series, No. 13, 2006 i DEEPENING DEMOCRACY AND ENHANCING SUSTAINABLE LIVELIHOODS IN UGANDA DEEPENING DEMOCRACY AND ENHANCING SUSTAINABLE LIVELIHOODS IN UGANDA An Independent Review of the Performance of Special Interest Groups in Parliament Arthur Bainomugisha Elijah D. Mushemeza ACODE Policy Research Series, No. 13, 2006 ii DEEPENING DEMOCRACY AND ENHANCING SUSTAINABLE LIVELIHOODS IN UGANDA TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS................................................................ iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................................................ iv EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.............................................................. v 1.0. INTRODUCTION............................................................. 1 2.0. BACKGROUND: CONSTITUTIONAL AND POLITICAL HISTORY OF UGANDA.......................................................... 2 3.0. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY................................................... 3 4.0. LEGISLATIVE REPRESENTATION AND ENVIRONMENTAL GOVERNANCE.................................................................... 3 5.0. UNDERSTANDING THE CONCEPTS OF AFFIRMATIVE ACTION AND REPRESENTATION.................................................. 5 5.1. Representative Democracy in a Historical Perspective............................................................. -

Chased Away and Left to Die

Chased Away and Left to Die How a National Security Approach to Uganda’s National Digital ID Has Led to Wholesale Exclusion of Women and Older Persons ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Publication date: June 8, 2021 Copyright © 2021 by the Center for Human Rights and Global Justice, Initiative for Social and Economic Rights, and Unwanted Witness. All rights reserved. Center for Human Rights and Global Justice New York University School of Law Wilf Hall, 139 MacDougal Street New York, New York 10012 United States of America This report does not necessarily reflect the views of NYU School of Law. Initiative for Social and Economic Rights Plot 60 Valley Drive, Ministers Village Ntinda – Kampala Post Box: 73646, Kampala, Uganda Unwanted Witness Plot 41, Gaddafi Road Opp Law Development Centre Clock Tower Post Box: 71314, Kampala, Uganda 2 Chased Away and Left to Die ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report is a joint publication by the Digital Welfare State and Human Rights Project at the Center for Human Rights and Global Justice (CHRGJ) based at NYU School of Law in New York City, United States of America, the Initiative for Social and Economic Rights (ISER) and Unwanted Witness (UW), both based in Kampala, Uganda. The report is based on joint research undertaken between November 2020 and May 2021. Work on the report was made possible thanks to support from Omidyar Network and the Open Society Foundations. Research and drafting for this report, both from Uganda and abroad, has been conducted by the following individuals (in alphabetical order with organizational affiliation): Katelyn Cioffi (CHRGJ), Kiira Brian Alex (ISER), Dorothy Mukasa (UW), Angella Nabwowe – Kasule (ISER), Salima Namusobya (ISER), Nattabi Vivienne (UW), Adam Ray (CHRGJ), Sempala Allan Kigozi (UW), and Christiaan van Veen (CHRGJ). -

From Uganda to the Congo and Beyond: Pursuing the Lord's Resistance Army

From Uganda to the Congo and Beyond: Pursuing the Lord's Resistance Army Ronald R. Atkinson DECEMBER 2009 INTERNATIONAL PEACE INSTITUTE Cover Photo: Men from the Ugandan ABOUT THE AUTHOR government local defense forces ride in the back of a militarized RONALD R. ATKINSON is Director of African Studies at the vehicle in Gulu, Uganda. July 31, University of South Carolina. He has lived and worked in 2003. © AP Photo/Marcus Kenya and Uganda in East Africa, Ghana in West Africa, Bleasdale. and South Africa. His major focus of research and writing is The views expressed in this paper the Acholi region and people in northern Uganda. represent those of the author and not necessarily those of IPI. IPI welcomes consideration of a wide ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS range of perspectives in the pursuit of a well-informed debate on critical IPI owes a great debt of thanks to the generous contribu - policies and issues in international tors to its Africa program. Their support reflects a affairs. widespread demand for innovative thinking on practical solutions to continental challenges. In particular, IPI and the IPI Publications Adam Lupel, Editor Africa program are grateful to the government of the Ellie B. Hearne, Publications Officer Netherlands. Suggested Citation The author is grateful to Adam Branch, Ed Carr, Denise Ronald R. Atkinson, “From Uganda Duovant, Sverker Finnström, and Eric Green for their astute to the Congo and Beyond: Pursuing and helpful comments on the penultimate draft. the Lord’s Resistance Army,” New York: International Peace Institute, December 2009. © by International Peace Institute, 2009 All Rights Reserved www.ipinst.org CONTENTS Executive Summary . -

“Keep the People Uninformed” Pre-Election Threats to Free Expression and Association in Uganda WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS “Keep the People Uninformed” Pre-election Threats to Free Expression and Association in Uganda WATCH “Keep the People Uninformed” Pre-election Threats to Free Expression and Association in Uganda Copyright © 2016 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-33139 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JANAURY 2016 ISBN 978-1-6231-33139 “Keep the People Uninformed” Pre-election Threats to Free Expression and Association in Uganda Map .................................................................................................................................... i Glossary of Acronyms and Terms ........................................................................................ ii Summary .......................................................................................................................... -

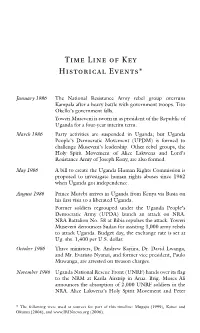

Time Line of Key Historical Events*

Time Line of Key Historical Events* January 1986 The National Resistance Army rebel group overruns Kampala after a heavy battle with government troops. Tito Okello’s government falls. Yoweri Museveni is sworn in as president of the Republic of Uganda for a four-year interim term. March 1986 Party activities are suspended in Uganda; but Uganda People’s Democratic Movement (UPDM) is formed to challenge Museveni’s leadership. Other rebel groups, the Holy Spirit Movement of Alice Lakwena and Lord’s Resistance Army of Joseph Kony, are also formed. May 1986 A bill to create the Uganda Human Rights Commission is proposed to investigate human rights abuses since 1962 when Uganda got independence. August 1986 Prince Mutebi arrives in Uganda from Kenya via Busia on his first visit to a liberated Uganda. Former soldiers regrouped under the Uganda People’s Democratic Army (UPDA) launch an attack on NRA. NRA Battalion No. 58 at Bibia repulses the attack. Yoweri Museveni denounces Sudan for assisting 3,000 army rebels to attack Uganda. Budget day, the exchange rate is set at Ug. shs. 1,400 per U.S. dollar. October 1986 Three ministers, Dr. Andrew Kayiira, Dr. David Lwanga, and Mr. Evaristo Nyanzi, and former vice president, Paulo Muwanga, are arrested on treason charges. November 1986 Uganda National Rescue Front (UNRF) hands over its flag to the NRM at Karila Airstrip in Arua. Brig. Moses Ali announces the absorption of 2,000 UNRF soldiers in the NRA. Alice Lakwena’s Holy Spirit Movement and Peter * The following were used as sources for part of this timeline: Mugaju (1999), Kaiser and Okumu (2004), and www.IRINnews.org (2006). -

Download PDF ~ Military of Uganda » ZIL8TEVQRMSO

NLZ36DMMDG3E \\ PDF > Military of Uganda Military of Uganda Filesize: 1.4 MB Reviews It in a of the best ebook. It is one of the most incredible pdf i actually have go through. I am just easily will get a satisfaction of looking at a composed book. (Elisha McCullough) DISCLAIMER | DMCA 8YWF5B4L0HMX > PDF < Military of Uganda MILITARY OF UGANDA To get Military of Uganda eBook, make sure you follow the web link beneath and save the file or gain access to other information that are highly relevant to MILITARY OF UGANDA ebook. Reference Series Books LLC Feb 2012, 2012. Taschenbuch. Book Condition: Neu. 254x192x5 mm. This item is printed on demand - Print on Demand Neuware - Source: Wikipedia. Pages: 41. Chapters: Military history of Uganda, Military schools in Uganda, Ugandan military personnel, Idi Amin, Uganda People's Defence Force, Yoweri Museveni, Kizza Besigye, Nobel Mayombo, James Kazini, David Oyite-Ojok, David Tinyefunza, Salim Saleh, Muhoozi Kainerugaba, 2008 2009 Garamba oensive, Elly Tumwine, Aronda Nyakairima, Akena p'Ojok, Katumba Wamala, Battle of Mengo Hill, Mugisha Muntu, Uganda Senior Command and Sta College, Jeje Odongo, Uganda National Liberation Front, University of Military Science and Technology, Uganda Junior Sta College, Odong Latek, List of military schools in Uganda, Uganda Military Academy, Internal Security Organisation, Dufile, Juma Oris, National Enterprise Corporation, Kale Kayihura, Nathan Mugisha, Francis Okello, Mustafa Adrisi, Moses Ali, Shaban Bantariza, Field Marshal, Levi Karuhanga. Excerpt: Yoweri Kaguta Museveni ( )) (born c. 1944) is a Ugandan politician and statesman. He has been President of Uganda since 26 January 1986. Museveni was involved in the war that deposed Idi Amin Dada, ending his rule in 1979, and in the rebellion that subsequently led to the demise of the Milton Obote regime in 1985. -

State Surveillance in Uganda

For God and My President: State Surveillance In Uganda For God and My President: State Surveillance In Uganda 1 Privacy International thanks the following individuals and organisations: BBC Newsnight Netzpolitik The Citizen Lab (University of Toronto, Canada) Claudio Guarnieri We also acknowledge the dozens of individuals and organisations in Uganda, the United Kingdom and Germany who cannot be named. A handful of these took significant risk to share information with us, for which we are grateful. This report is primarily based on original documentation provided in confidence to Privacy International. Privacy International is solely responsible for the content of this report. For God and My President: State Surveillance In Uganda For God and My President: State Surveillance In Uganda October 2015 www.privacyinternational.org 3 For God and My President: State Surveillance In Uganda Chieftaincy of Military Intelligence building, Mbuya Hill, 2012. Photo obtained by Privacy International. 4 For God and My President: State Surveillance In Uganda List of Acronyms A4C Activists for Change CCTV Closed-Circuit Television CDF Chief of Defence Forces CIID Police Criminal Investigations and Intelligence Directorate CMI Chieftaincy of Military Intelligence ESO External Security Organisation FDC Forum for Democratic Change ICT Information and Communication Technology IGP Inspector General of Police ISO Internal Security Organisation IT Information Technology JIC Joint Intelligence Committee LAN Local Area Network MP Member of Parliament NRA National Resistance Army NRM National Resistance Movement RICA Regulation of Interception of Communications Act (2010) UCC Uganda Communications Commission UPDF Uganda People's Defence Force UPF Uganda Police Force 5 For God and My President: State Surveillance In Uganda Executive Summary Yoweri Museveni was re-elected to his fifth term as President of Uganda in February 2011.