Journal of Terrorism Research, Volume 4, Issue 1 (2013)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interrogato Daj Giudici L'ex Capo Del SID Grave Offensiva Contro L

r Unità 7 venerdì 8 novembre 1974 PÀG. 5 / cronache u » t Otto nuovi provvedimenti firmati dal giudici che Indagano sul tentativo di Borghese Nuovi mandati di cattura per il golpe Tra gli arrestati esponenti del MSI Cinque sono finiti in carcere, tre sono riusciti a fuggire - Tra questi il consigliere regionale missino della Valle d'Aosta, Parisi - Manette a Zanelli dirigente provinciale alla Spezia del partito neofascista - Spiccati una ventina di avvisi di reato e oltre cinquanta comunicazioni giudiziarie Altri otto mandati di cattura, di cui cinque eseguiti Ieri mattina, una ventina di avvisi di reato e 50 comunicazioni giudiziarie sono il bilancio della nuova e tornata » di Indagini della magistratura romana sul golpe Borghese del dicembre 1970. Il • giudice istruttore Filippo Fiore, su richiesta del PM Claudio Vltalone, ha fatto arrestare dagli agenti del Processo al commando nero di Varese nucleo di polizia giudiziaria Benito Guadagni, romano, che fu uno dei più stretti collabo VARESE, 7 vanni, di 21 anni, esponente delle SAM, un ratori di Borghese, costruttore edile; Tommaso Adami Rock, fiorentino, ingegnere, già se- • Con la concessione di meno di ventlquat- • « sambabillno », colpito da mandato di cat ; ; . gretario provinciale e candi . tr'ore di tempo a favore della difesa, si è tura del giudice istruttore di Rieti «per in dato al consiglio comunale conclusa stamane, in poco più di un'ora e surrezione armata contro lo Stato, attentato per il MSI; Adriano Mon ' mezza, la prima udienza del procedimento alla Costituzione, associazione sovversiva e ti medico di Rieti, Giuseppe < per direttissima nel confronti del quattro Zanelli di La Spezia, dirigen • neofascisti arrestati a Varese il 27 ottobre ricostituzione del dlsclolto partito fascista ». -

Contemporary Italy: Literature, Cinema, Politics and Culture SRISA Course Number: POLI 3102 Maryville Course Number: PSCI 370 Credits: 3, Contact Hours: 45

Lecture Course Santa Reparata International School of Art Course Syllabus Semester Course Course Title: History of Contemporary Italy: Literature, Cinema, Politics and Culture SRISA Course Number: POLI 3102 Maryville Course Number: PSCI 370 Credits: 3, Contact Hours: 45 1. COURSE DESCRIPTION In this course students will study the history of Contemporary Italy from WWII (the 1940’s and the birth of the Italian Republic) and continue on through to the development and the radical change of the country during the 1960’s, the long Anni Settanta and the so called “years of lead”, contemporary Italian politics up through most recent historical events. Introduction to major literary, cinematographic and artistic movements are covered as well as social aspects of Italian life including topics such as the Italian political system; the development of the Italian educational system; the roots and influence of the Italian Mafia; and the changing role of women in Italian society. 2. CONTENT INTRODUCTION This course introduces students to the history and politics of contemporary Italy from the time of WWII to the present. The course is divided into five parts, with the first part focusing on the transformation of the country and its eventual industrialization. We will study the reconstruction and economic boom of the 1950s and 1960s, social post-war conflict, and the year 1968 - with the student and worker protests - and the final changing of Italian social geography. Great importance will be given to internal migration, from south to north and to the development of the Mafia. The second part of the course focuses on the history of the 1970s, later called the “Years of Lead”, because of terrorist escalation culminating with the assassination of MP Aldo Moro in May 1978 by the Red Brigades. -

“The Black Virus”

“THE BLACK VIRUS” By Giorgio Mottola Consultant Andrea Palladino With the contribution of Norma Ferrara – Simona Peluso Video by Dario D’India – Alfredo Farina Video by Davide Fonda – Tommaso Javidi Editing and graphics by Giorgio Vallati GIORGIO MOTTOLA OFF CAMERA How a video by the news show TGR Leonardo went viral is a rather unusual story. It was extremely difficult to find on search engines. So, for five years the story remained buried in the RAI website's archive – until last month, it had zero views. SIGFRIDO RANUCCI IN THE STUDIO This video appeared on social media and on our mobile phones while we were at home in lockdown, somewhat nettled by the long, enforced quarantine. It was an old TGR Leonardo report, showing Chinese reporters in a lab, experimenting on a strain of coronavirus. And we all shared the same suspicion. The SARS-CoV-2 strain is manmade, the poisoned fruit of Chinese researchers. We all posted it on our profiles, including me, though I pointed out that scientists had excluded any human intervention and that the video was spreading quicker than coronavirus. Who pushed it so far? Who made it go viral? With what intent? And, above all, was it real or fake news? There's a fine line there. GIORGIO MOTTOLA OFF CAMERA If you have a social network profile or just use WhatsApp, while locked away at home you will certainly have seen this video. TGR LEONARDO – FROM 16/11/2015 It's an experiment, sure, but it's worrying. It worries many scientists. A team of Chinese researchers inserts a protein taken from bats into a SARS virus strain, or acute pneumonia, obtained from mice. -

George Gittoes: I Witness Teachers' Notes

GEORGE GITTOES: I WITNESS TEACHERS’ NOTES George Gittoes, Evolution 2014, oil on paper INTRODUCTION “I believe in art so much that I am prepared to risk my life to do it. I physically go to these places. I also believe an artist can actually see and show things about what's going on that a paid professional journalist can't and won't do, and can show a level of humanity and complexity that they wouldn't cover on TV.” - George Gittoes George Gittoes: I Witness is the first major exhibition in Australia of the work of artist and film maker George Gittoes which surveys the last 45 years of his incredible career. Internationally recognised for working and creating art in regions of conflict around the world he has been an eye witness to war and human excess, and also to the possibilities of compassion. Beginning his career in the late 1960s, Gittoes was part of a group of artists including Brett Whiteley and Martin Sharp who established The Yellow House artist community in Sydney. This was followed by his move to Bundeena in the Sutherland region where he became an influential and instrument figure in community art projects and the development of Hazelhurst Regional Gallery and Arts Centre. In the 1980s Gittoes began travelling to areas of conflict and his tireless energy for pushing the boundaries of art making has since seen him working in some of the most dangerous and difficult places on earth. He first travelled to Nicaragua and the Philippines, then the Middle East, Rwanda and Cambodia in the 1990s and more recently to Iraq and Afghanistan. -

Investigating Italy's Past Through Historical Crime Fiction, Films, and Tv

INVESTIGATING ITALY’S PAST THROUGH HISTORICAL CRIME FICTION, FILMS, AND TV SERIES Murder in the Age of Chaos B P ITALIAN AND ITALIAN AMERICAN STUDIES AND ITALIAN ITALIAN Italian and Italian American Studies Series Editor Stanislao G. Pugliese Hofstra University Hempstead , New York, USA Aims of the Series This series brings the latest scholarship in Italian and Italian American history, literature, cinema, and cultural studies to a large audience of spe- cialists, general readers, and students. Featuring works on modern Italy (Renaissance to the present) and Italian American culture and society by established scholars as well as new voices, it has been a longstanding force in shaping the evolving fi elds of Italian and Italian American Studies by re-emphasizing their connection to one another. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/14835 Barbara Pezzotti Investigating Italy’s Past through Historical Crime Fiction, Films, and TV Series Murder in the Age of Chaos Barbara Pezzotti Victoria University of Wellington New Zealand Italian and Italian American Studies ISBN 978-1-137-60310-4 ISBN 978-1-349-94908-3 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-349-94908-3 Library of Congress Control Number: 2016948747 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifi cally the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfi lms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. -

La Strategia Della Tensione E La Teoria Del Doppio Stato

%*1"35*.&/50%*4$*&/;&10-*5*$)& $"55&%3"%*4503*"$0/5&.103"/&" -"453"5&(*"%&--"5&/4*0/&&-"5&03*"%&-%011*045"50 3&-"503& $"/%*%"50 1SPG'FEFSJDP/JHMJB "MFYBOEFS%J*BOOJ .BUSJDPMB "//0"$$"%&.*$0 Indice: Capitolo I: L’avvento degli anni di piombo 6 1.1 Il Sessantotto ed i movimenti studenteschi. 6 1.1.1 Le lotte operaie e l’«autunno caldo». 10 1.2 L’evoluzione degli scontri di piazza e gli attentati dinamitardi. 13 1.2.1 Piazza Fontana. 18 1.3 Il sogno del golpe e lo stragismo: Peteano, Brescia e la strage del treno Italicus. 20 1.4 La strage di Bologna e le verità inconfessate. 27 Capitolo II: Dibattito sullo Stato «parallelo» 30 2.1 La nascita del Sid e il suo ruolo nella Strategia della tensione. 30 2.2 I protocolli segreti dell’Alleanza Atlantica, il Sid «parallelo» e l’enigma di Capo Marrargiu. 39 2 Introduzione: Cos’è la Strategia della tensione? Davvero, il periodo della storia italiana, che va dal 1969 al 1975, caratterizzato da molteplici tentativi di golpe e dallo stragismo, è stato manovrato da determinati servizi segreti «paralleli»? I servizi segreti italiani, sono stati «deviati» ed inquinati da singoli elementi che hanno operato al loro interno? E fino a che punto, le superpotenze, come gli Stati Uniti d’America, hanno condizionato le scelte italiane in questo settore? Si può davvero dimostrare l’esistenza di uno Stato «parallelo», e di conseguenza confermare la cosiddetta Teoria del «Doppio» Stato? Queste, le ipotesi avanzate. L’elaborato, non pretende di dare una risposta alla miriade di interrogativi: fornisce piuttosto, una analisi storiografica ben dettagliata e rigorosa fino al possibile, affinché possa essere gettata un po' di luce, su questa «oscura pagina» della storia italiana. -

Gli Anni Di Piombo Nella Letteratura E Nell'arte Degli Anni Duemila

Facultad de Filología Departamento de Filología Moderna Área de Estudios italianos Gli anni di piombo nella letteratura e nell’arte degli anni Duemila TESIS DOCTORAL AUTORA: LILIA ZANELLI DIRECTORA: CELIA ARAMBURU SÁNCHEZ SALAMANCA 2018 II Esta Tesis Doctoral ha sido realizada bajo la dirección de la Profesora Celia Aramburu Sánchez Fdo. III IV Non posso terminare questo lavoro senza ringraziare, in primo luogo, la professoressa Celia Aramburu Sánchez, per gli insegnamenti ed il tempo che mi ha dedicato fin dall’inizio di questa ricerca, per la pazienza nel rispondere ai tanti dubbi che le sottoponevo, per la passione con la quale abbiamo condiviso questo tema, per avermi saputo orientare, consigliare, correggere, e non ultimo incoraggiare durante questi anni. Grazie anche a tutti i professori dell’Área de Estudios italianos dell’Università di Salamanca i cui insegnamenti spero di essere riuscita a plasmare nell’elaborazione di questa tesi. Un ringraziamento speciale anche alla professoressa Alessandra Zanobetti che è stata mia tutor durante il mio soggiorno presso l’università di Bologna e che ho ritrovato con piacere dopo tanti anni, senza la quale la ricerca riguardante la parte giuridica di questa tesi non sarebbe stata possibile. Grazie alla mia famiglia e poi agli amici più cari che hanno sopportato le assenze, le preoccupazioni ed incertezze e in particolare a mio cugino Maurizio Morini, testimone diretto degli “anni di piombo” e fonte di ispirazione. Grazie, Javier e Paola, per il vostro amore, per l’aiuto enorme che mi avete prestato e per avere sempre creduto in me. V VI Indice ABBREVIATURE IMPIEGATE XIII INTRODUZIONE 1 1. -

Annual Report 2013-2014

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston Arts, Fine of Museum The μ˙ μ˙ μ˙ The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston annual report 2013–2014 THE MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, HOUSTON, WARMLY THANKS THE 1,183 DOCENTS, VOLUNTEERS, AND MEMBERS OF THE MUSEUM’S GUILD FOR THEIR EXTRAORDINARY DEDICATION AND COMMITMENT. ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL 2013–2014 Cover: GIUSEPPE PENONE Italian, born 1947 Albero folgorato (Thunderstuck Tree), 2012 Bronze with gold leaf 433 1/16 x 96 3/4 x 79 in. (1100 x 245.7 x 200.7 cm) Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund 2014.728 While arboreal imagery has dominated Giuseppe Penone’s sculptures across his career, monumental bronzes of storm- blasted trees have only recently appeared as major themes in his work. Albero folgorato (Thunderstuck Tree), 2012, is the culmination of this series. Cast in bronze from a willow that had been struck by lightning, it both captures a moment in time and stands fixed as a profoundly evocative and timeless monument. ALG Opposite: LYONEL FEININGER American, 1871–1956 Self-Portrait, 1915 Oil on canvas 39 1/2 x 31 1/2 in. (100.3 x 80 cm) Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund 2014.756 Lyonel Feininger’s 1915 self-portrait unites the psychological urgency of German Expressionism with the formal structures of Cubism to reveal the artist’s profound isolation as a man in self-imposed exile, an American of German descent, who found himself an alien enemy living in Germany at the outbreak of World War I. -

Introduction to Part I

2_BULL-INTRO1P017-028 3/10/07 15:04 Page 17 Part I Villains? The Judicial Truth 2_BULL-INTRO1P017-028 3/10/07 15:04 Page 18 2_BULL-INTRO1P017-028 3/10/07 15:04 Page 19 Introduction to Part I Stragismo, as discussed in Chapter 1, refers to a bombing campaign which started in the late 1960s and lasted for several years, causing a high toll in terms of the number of people killed and wounded. Initially, investigations targeted extreme- left, especially anarchist, groups (the so-called ‘red trail’), since the available evi- dence appeared to point in their direction. Later investigations started to probe an alternative path, the so-called ‘black trail’, which pointed the finger at extreme- right groups as the culprits for the massacres, albeit acting in ways that would pin the blame upon the extreme left. In connection to this discovery, investigating magistrates also brought to light the existence of a strategy, which became widely known as the Strategy of Tension, whose aim was to create an atmosphere of sub- version and fear in the country so as to promote a turn to an authoritarian type of government. Since the strategy was mainly directed at containing communism in Italy (especially in the light of the formation of centre-left governments from 1963, and increasing unrest on the part of students and workers in 1968 and 1969), it was an essential part of this strategy that the threat of political subversion should be seen as coming from the left, not from the right. This explained to many why much of the early evidence had appeared to point in the direction of anarchist groups. -

Violence in Newspaper's Language

Violence in newspaper’s language Alessia Zocca Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg Universität Basel [email protected] This study investigates the relationship between violence and language. It is based on the linguistic analysis of one page of the Italian national daily La Stampa. The issue took under consideration was published after a violent episode during the so- called Anni di Piombo [‘Years of Lead’] in Italy: the bombing at the Bologna railway Station occurred on August 2, 1980. The analysis of the language is organized on three different levels: lexis, morphology and syntax. Keywords: Violence; newspaper; Bologna Massacre 1. Introduction Violence is recognizable in several situations in which human beings are involved. Is it possible to identify it in language too? This paper is part of a bigger research involving the linguistic analysis of seven Italian newspapers and the goal is to study the language used in the account of different violent episodes. The idea of recognizing violence in language was born of a primary need to discover its reproducibility. Is it possible that the word manages to reproduce the violence? If it does succeed in doing so, what tools are used? The analysis in this paper demonstrates that violence can be part of language, not only in its content, but also in its form. The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 introduces the meaning of violence, whereas Section 3 presents violence in recent Italian History, examining in particular the Bologna Massacre. Section 4 consists of an explanation of the meaning of violence with reference to language. In Section 5 the issue of the Italian newspapers La Stampa, published on August, 3 1980 following the events of the Bologna Massacre, is analyzed. -

Printmaking and the Language of Violence

PRINTMAKING AND THE LANGUAGE OF VIOLENCE by Yvonne Rees-Pagh Graduate Diploma of Arts (Visual Arts) Monash University Master Of Visual Arts Monash University Master of Fine Arts University of Tasmania Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmania MARCH 2013 This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. YVONNE REES-PAGH MARCH 2013 i This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying and communication in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. YVONNE REES-PAGH MARCH 2013 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge and thank my supervisors Milan Milojevic and Dr Llewellyn Negrin for their advice, assistance and support throughout the project. I am eternally grateful to my partner in life Bevan for his patience and encouragement throughout the project, and care when I needed it most. DEDICATION I dedicate this project to the memory of my dearest friend Olga Vlasova, the late Curator of Prints, Russian Museum, St Petersburg. Printmaking brought us together in a lasting friendship that began in Tomsk, Siberia in 1990. iii CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................................................. 01 Introduction ....................................................................................... 02 Chapter One: The Central Argument Towards violence ..................................................................... 07 Violence and the power of etching .......................................... -

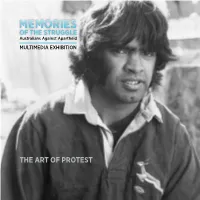

The Art of Protest

MULTIMEDIA EXHIBITION 1 THE ART OF PROTEST MEMORIES OF THE STRUGGLE – MULTIMEDIA EXHIBITION THE ART OF PROTEST THE ART OF PROTEST 2014 Customs House Sydney University of Pretoria MEMORIES OF THE STRUGGLE – MULTIMEDIA EXHIBITION 2016 Museum of Australian Democracy Canberra Protest in Sydney including from left to right Eddie Funde, ACTU President Cliff Dolan, Maurie Keane MP, Senator 2017 The Castle of Good Hope Bruce Childs and Johnny Makateni. Photo: State Library of NSW & Search Foundation Cape Town Voices and Memories ANGUS LEENDERTZ | CURATOR THE ASAA TEAM CONTRIBUTORS The global anti-apartheid movement was arguably the greatest social movement of CURATOR Angus Leendertz Father Richard Buchhorn the 20th century and Australia can be very proud of the important role it played in Will Butler and Pamela Curry – Australian High Commission Pretoria, ASSISTANT CURATORS the demise of apartheid. The history of the anti-apartheid movement in Australia Tracy Dunn (Director Ephemera Research & Logistics, University of Pretoria Exhibition 2014 Collections) & James Mohr David Corbet – University of Pretoria Catalogue Design from 1950 to1994 was a story waiting to be told. Ken Davis & Dr Helen McCue – APHEDA (Union Aid Abroad) MUSEUM OF AUSTRALIAN Introduction DEMOCRACY CURATOR Professor Andrea Durbach – HRC Centre, University of New South Wales Libby Stewart Professor Gareth Evans – Former Australian Mininister of Foreign Affairs In this exhibition, you will hear the voices and In 1997, I responded to Nelson Mandela’s general call memories of some of the Australians, South Africans for skilled South Africans to return to their country ASAA REFERENCE GROUP Dr Gary Foley – Victoria University and people of other nations who worked hard of birth and assist in building the new free South Kerry Browning Eddie Funde – ANC Australia over decades to bring about the end of apartheid.