1 Drones and Night Vision

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

George Gittoes: I Witness Teachers' Notes

GEORGE GITTOES: I WITNESS TEACHERS’ NOTES George Gittoes, Evolution 2014, oil on paper INTRODUCTION “I believe in art so much that I am prepared to risk my life to do it. I physically go to these places. I also believe an artist can actually see and show things about what's going on that a paid professional journalist can't and won't do, and can show a level of humanity and complexity that they wouldn't cover on TV.” - George Gittoes George Gittoes: I Witness is the first major exhibition in Australia of the work of artist and film maker George Gittoes which surveys the last 45 years of his incredible career. Internationally recognised for working and creating art in regions of conflict around the world he has been an eye witness to war and human excess, and also to the possibilities of compassion. Beginning his career in the late 1960s, Gittoes was part of a group of artists including Brett Whiteley and Martin Sharp who established The Yellow House artist community in Sydney. This was followed by his move to Bundeena in the Sutherland region where he became an influential and instrument figure in community art projects and the development of Hazelhurst Regional Gallery and Arts Centre. In the 1980s Gittoes began travelling to areas of conflict and his tireless energy for pushing the boundaries of art making has since seen him working in some of the most dangerous and difficult places on earth. He first travelled to Nicaragua and the Philippines, then the Middle East, Rwanda and Cambodia in the 1990s and more recently to Iraq and Afghanistan. -

Annual Report 2013-2014

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston Arts, Fine of Museum The μ˙ μ˙ μ˙ The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston annual report 2013–2014 THE MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, HOUSTON, WARMLY THANKS THE 1,183 DOCENTS, VOLUNTEERS, AND MEMBERS OF THE MUSEUM’S GUILD FOR THEIR EXTRAORDINARY DEDICATION AND COMMITMENT. ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL 2013–2014 Cover: GIUSEPPE PENONE Italian, born 1947 Albero folgorato (Thunderstuck Tree), 2012 Bronze with gold leaf 433 1/16 x 96 3/4 x 79 in. (1100 x 245.7 x 200.7 cm) Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund 2014.728 While arboreal imagery has dominated Giuseppe Penone’s sculptures across his career, monumental bronzes of storm- blasted trees have only recently appeared as major themes in his work. Albero folgorato (Thunderstuck Tree), 2012, is the culmination of this series. Cast in bronze from a willow that had been struck by lightning, it both captures a moment in time and stands fixed as a profoundly evocative and timeless monument. ALG Opposite: LYONEL FEININGER American, 1871–1956 Self-Portrait, 1915 Oil on canvas 39 1/2 x 31 1/2 in. (100.3 x 80 cm) Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund 2014.756 Lyonel Feininger’s 1915 self-portrait unites the psychological urgency of German Expressionism with the formal structures of Cubism to reveal the artist’s profound isolation as a man in self-imposed exile, an American of German descent, who found himself an alien enemy living in Germany at the outbreak of World War I. -

Printmaking and the Language of Violence

PRINTMAKING AND THE LANGUAGE OF VIOLENCE by Yvonne Rees-Pagh Graduate Diploma of Arts (Visual Arts) Monash University Master Of Visual Arts Monash University Master of Fine Arts University of Tasmania Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmania MARCH 2013 This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. YVONNE REES-PAGH MARCH 2013 i This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying and communication in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. YVONNE REES-PAGH MARCH 2013 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge and thank my supervisors Milan Milojevic and Dr Llewellyn Negrin for their advice, assistance and support throughout the project. I am eternally grateful to my partner in life Bevan for his patience and encouragement throughout the project, and care when I needed it most. DEDICATION I dedicate this project to the memory of my dearest friend Olga Vlasova, the late Curator of Prints, Russian Museum, St Petersburg. Printmaking brought us together in a lasting friendship that began in Tomsk, Siberia in 1990. iii CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................................................. 01 Introduction ....................................................................................... 02 Chapter One: The Central Argument Towards violence ..................................................................... 07 Violence and the power of etching .......................................... -

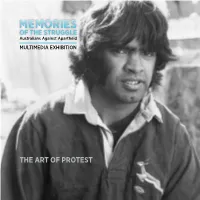

The Art of Protest

MULTIMEDIA EXHIBITION 1 THE ART OF PROTEST MEMORIES OF THE STRUGGLE – MULTIMEDIA EXHIBITION THE ART OF PROTEST THE ART OF PROTEST 2014 Customs House Sydney University of Pretoria MEMORIES OF THE STRUGGLE – MULTIMEDIA EXHIBITION 2016 Museum of Australian Democracy Canberra Protest in Sydney including from left to right Eddie Funde, ACTU President Cliff Dolan, Maurie Keane MP, Senator 2017 The Castle of Good Hope Bruce Childs and Johnny Makateni. Photo: State Library of NSW & Search Foundation Cape Town Voices and Memories ANGUS LEENDERTZ | CURATOR THE ASAA TEAM CONTRIBUTORS The global anti-apartheid movement was arguably the greatest social movement of CURATOR Angus Leendertz Father Richard Buchhorn the 20th century and Australia can be very proud of the important role it played in Will Butler and Pamela Curry – Australian High Commission Pretoria, ASSISTANT CURATORS the demise of apartheid. The history of the anti-apartheid movement in Australia Tracy Dunn (Director Ephemera Research & Logistics, University of Pretoria Exhibition 2014 Collections) & James Mohr David Corbet – University of Pretoria Catalogue Design from 1950 to1994 was a story waiting to be told. Ken Davis & Dr Helen McCue – APHEDA (Union Aid Abroad) MUSEUM OF AUSTRALIAN Introduction DEMOCRACY CURATOR Professor Andrea Durbach – HRC Centre, University of New South Wales Libby Stewart Professor Gareth Evans – Former Australian Mininister of Foreign Affairs In this exhibition, you will hear the voices and In 1997, I responded to Nelson Mandela’s general call memories of some of the Australians, South Africans for skilled South Africans to return to their country ASAA REFERENCE GROUP Dr Gary Foley – Victoria University and people of other nations who worked hard of birth and assist in building the new free South Kerry Browning Eddie Funde – ANC Australia over decades to bring about the end of apartheid. -

Australia's Refugee Policy

' i I I I ' boo~ offer! The Elements of Style STWILLIAM . By William Strunk Jr & E.B . White RUNKJR. Last month a boxer pup called Becky ate a large chunk of that pocket classic of lucid instruction, Strunk and White's The Elements of Style. The dog belonged to our columnist, Brian Matthews (see page 33). N ext issue we expect Becky to write E.s.WHITE her first column for Eurel<a Street. While waiting for that, why don't you write in for a copy of this most elegant, efficient and amiable of language handbooks? Strunk and White reads like the ideal style guide for the speeches you wish an American president would make. And even with appendices it is still smaller than a Football Record. You could insinuate it into board meetings, book clubs, classrooms or courtrooms without marring the line of your jeans. Or you could read it in bed, to give your brain delight and your wrists a rest from those large-format paperbacks destined to have an afterlife as doorstoppers. Thanks to Readings Books and Music, Eurel<a Street has 10 copies of The Elements of STYLE Style, fourth edition, to give away. Just put your name and address on the back of an envelope and send to: Eureka Street July- FOURTH EDITION August 2002 Book Offer, PO Box 553, mgs• Richmond VIC 3 121 . See page 8 for winners FOREWORD BY ROGER ANGELL of the May 2002 Book Offer. -- T l1 e -------------- MELB() RNE STREEI ----------- - UNml "Someti mes you j ust need to sing Blessed present Assurance and hit a tambourine." Rowan Williams, Archbishop of Wales and Australia's Refugee Policy possible next Archbishop of Canterbury Facts, needs and limits "We all have to cope with evil, whether Speakers: we can expla in it adequately or not. -

Contemporary Art and Political Violence: the Role of Art in the Rehabilitation and Healing of Communities Affected by Political Violence Christiana Spens*

Contemporary Art and Political Violence: The Role of Art in the Rehabilitation and Healing of Communities Affected by Political Violence Christiana Spens* Abstract: This paper will investigate how contemporary artists who use political violence as a subject matter in their work explain the relationship between art and that form of violence. Referring to interviews with Anita Glesta and George Gittoes, the potential of art as a means of healing communities and individuals affected by terrorism will be explored, alongside related issues of voyeurism, sensationalism and commercialism in art. The study will refer to the ideas of Collingwood and Tolstoy, chosen so as to represent two main schools of thought regarding artistic responsibility & morality and the appropriate intentions of artists. I will explain that both theories can be applied harmoniously to contemporary practise, to the understanding of the role and responsibility of contemporary artists, and discourse around the wider social value of contemporary art. Introduction Contemporary art is used as a means for rehabilitating and healing communities affected by political violence in various ways, from the use of art therapy in the rehabilitation of prisoners and victims, to the wider use of art as a communal experience that enables shared memory and compassion in particular groups of people. The idea of art as useful for this rehabilitation and healing of communities has its roots in the notion of ‘moral art’ (Tolstoy, 1996: 223 – 224), or art that is socially responsible. In aesthetics and the philosophy of art, there are two broad schools of thought regarding how art can be socially valuable. -

Elizabeth Woodhams Thesis (PDF 1MB)

Application for the Award of Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Thesis Title Memories are Not Silence: the trauma of witnessing and art making. A Phenomenological exploration of my lived experience as an artist. Candidate Elizabeth Jean Deshon Woodhams, BTh., MA 2004 Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy with the Creative Industries Research and Application Centre (CIRAC) at Queensland University of Technology (QUT) i TITLE OF THESIS: Memories are Not Silence; the trauma of witnessing and art making. A phenomenological exploration of my lived experiences as an artist. ABSTRACT This research investigates formative and definitive lived experiences as two narrative forms - art works and writing. The research seeks to uncover the essential features of these experiences (dominated as they are by my experiences of AIDS and the after effects of war) and bring the two narratives together as a reflexive and reflective dialogue. The 'lens' of my art practice (both written and visual) is predominantly that of a landscape painter -be it 'landscape of faces' (portraits), landscapes of the human form (figurative) or the more traditional descriptions of landscape (especially deserts). Phenomenological research is a particular mode of describing and understanding the contours of lived experience. By a process of self-reflection and critical analysis this research explores various understandings of landscape so as to uncover their structure and meaning and to come to a deeper understanding of how those elements influence my art making. KEY WORDS: memories, silence, art, artists, women artists, art making, trauma, witnessing, phenomenological research, lived experience, writing, HIV/AIDS, hetrosexual voices, war. -

Visiting the Rwandan Genocide Memorial Site at Murambi, Gikongoro

PERFORMANCE PARADIGM 3 (2007) Jeff Stewart Being Near: Visiting the Rwandan Genocide Memorial Site at Murambi, Gikongoro Just as in our personal lives our worst fears and best hopes will never adequately prepare us for what actually happens, because the moment even a foreseen event takes place, everything changes, and we can never be prepared for the inexhaustible literalness of this ‘everything’… (Arendt, 1953: 389). Opening There is a trauma about being in Rwanda for me that needs to be acknowledged. This ‘everything’ that changes manifests in moments of ‘awakening’ in the sense suggested by Cathy Caruth: As an awakening, the ethical relation to the real is the revelation of this impossible demand (of responsibility) at the heart of human consciousness (Caruth, 1995: 100). This is a compelling demand. Bearing Witness This writing (Being Near) is concerned with a recent trip to Rwanda (April 2006) where I visited five of the major genocide memorial sites in the east, west and south of the country. The primary site for Being Near is Murambi, Gikongoro, to the south west of the capital Kigali. While conducting research for my thesis I heard the ABC’s World Today radio program presented by the Australian journalist Sally Sara from the school at this site (Sara, 2003). Following her report I began to look into the genocide and it became apparent that it was important for me to visit and witness Murambi, to travel to Rwanda, to be in this place; to STEWART | 75 PERFORMANCE PARADIGM 3 (2007) continue my research without visiting would have been in this instance to take what I thought would be a too distant, objective position denying the humanity of those who were still lying at Murambi. -

Conflict-Related Sexual and Gender-Based Violence: an Introductory Overview to Support Prevention and Response Efforts (1/2014)

Civil-MilitaryCivil-Military Occasional Occasional Papers Papers Women,Conflict-related Peace and SecuritySexual and ReflectionsGender-based from Australian maleViolence leaders An Introductory Overview to Support Prevention and Response Efforts 4/20151/2014 EditedSarah by Shteir, Helena Australian Studdert Civil-Military and Sarah Shteir Centre > WWW.ACMC.GOV.AU Acknowledgments: The editors would like to express their thanks to the contributors of this collection. They were generous with their time, flexibility and contributions. Photo credits: Cover photo: Chief Petty Officer Leo Vredenbregt p. 10: Australian War Memorial/Wayne Ryan, CAMUN/92/067/17 p. 12: Australian War Memorial/George Gittoes, P01744.019 p. 17: Chief Petty Officer Leo Vredenbregt p. 20: Commonwealth of Australia/SGT Brent Tero p. 30: ActionAid Australia pp. 39 and 41: Australian Federal Police pp. 44, 46, 54: DFAT/Bernard Philip p. 57: Commonwealth of Australia/ABIS Jo Dilorenzo p. 64: US 7th Fleet Public Affairs Disclaimer: The views expressed in this Civil-Military Occasional Paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Australian Civil-Military Centre or of any government agency. Authors enjoy the academic freedom to offer new and sometimes controversial perspectives in the interest of furthering debate on key issues. The content is published under a Creative Commons by Attribution 3.0 Australia (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/) licence. All parts of this publication may be reproduced, stored in retrieval systems, -

24 March 2021 Senator the Hon Marise Payne Minister for Foreign

24 March 2021 Senator the Hon Marise Payne Minister for Foreign Affairs Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Minister, We, the undersigned, are Laureates of the Sydney Peace Prize, which is awarded by the Sydney Peace Foundation, a Foundation of the University of Sydney, in partnership with the City of Sydney. We are deeply alarmed by the recent events in Myanmar, which have been called “crimes against humanity” by the UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights, Tom Andrews. While the February 1 coup has captured the attention of the international community, the actions of Myanmar’s military, the Tatmadaw, have been a threat to international peace and security for a long time. In response to peaceful protests, the military has committed acts of murder, enforced disappearance, persecution, torture, and imprisonment, in violation of fundamental rules of international law. These crimes, Andrews has noted, are "widespread," "systematic," and "coordinated." They also mirror the actions that the military has taken against ethnic minority groups in Myanmar for years, including alleged genocide against the Rohingya and war crimes and crimes against humanity against other ethnic and religious minorities in Kachin and Shan States. Given Australia’s influence in the region, you have a unique opportunity to promote peace and human rights by immediately increasing the scope of sanctions on the organisers of the coup and ensuing crimes against humanity, cancelling Australia’s defence cooperation program with Myanmar, rejecting an illegal regime, and supporting the return of the democratically elected Government of Myanmar. The military leadership behind this coup should be investigated under international law for allegations of genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes against the Rohingya population of Myanmar and war crimes and crimes against humanity against other ethnic and religious minorities in Kachin and Shan States. -

George Gittoes: I Witness Education Kit Visual Arts Stage 5 & 6

GEORGE GITTOES: I WITNESS EDUCATION KIT VISUAL ARTS STAGE 5 & 6 George Gittoes, Evolution 2014, oil on paper ABOUT THIS EDUCATION KIT OVERVIEW OF THE RESOURCE This resource has been developed to support teaching and learning for George Gittoes: I Witness. The Education Kit contains information about each of the key periods of Gittoes’ practice, as identified by curator Rod Pattern, explored in this survey spanning the last 45 years. Each section is accompanied by an example of his work from that time with an extended description and artist quote. There is a series of questions that focus on examining selected works through the Frames, Conceptual Framework along with questions about his Practice. CURRICULUM LINKS Stage 5 5.7, 5.8, 5.9, 5.10 Stage 6 P7, P8, P9, P10 and H7, H8, H9, H10 CONTENTS Introduction – page 2 In the Beginning: The Yellow House – page 3 The Revolutionary Artist: The Philippines –page 4 The Realism of Peace Within War: Cambodia, The Middle East and South Africa – page 5 Between Life and Death: Kibeho, Rwanda – pages 6, 7 and 8 Art in the Age of Terrorism: Afghanistan, New York, Iraq and Pakistan – pages 9 and 10 Descendence – The Soldier in War – page 11 INTRODUCTION “I believe in art so much that I am prepared to risk my life to do it. I physically go to these places. I also believe an artist can actually see and show things about what's going on that a paid professional journalist can't and won't do, and can show a level of humanity and complexity that they wouldn't cover on TV.” - George Gittoes George Gittoes: I Witness is the first major exhibition in Australia of the work of artist and film maker George Gittoes which surveys the last 45 years of his incredible career. -

SNOW MONKEY Directed by George Gittoes

SNOW MONKEY Directed by George Gittoes Australia + Norway / 2015 / English, Pashtu, Arabic / 148 min. / International premiere Publicity Contact IDFA: Silversalt PR Thessa Mooij [email protected] US +1.646.637.4700 NL +31.6.4151.5717 1 LOGLINE Eager to create art with local talent in the path of the war machine, Australian artist GEORGE GITTOES recruits gangs of war-damaged children in one of Afghanistan’s most violent cities to shoot local Pashto-style films. SHORT SYNOPSIS For almost 50 years, activist artist George Gittoes has stood on the frontlines of the world's most brutal conflicts and borne witness to the best and the worst of humanity. Now living in Afghanistan's remote Jalalabad province, Gittoes turns his attention to the lives of the children and outcasts of this war-torn land as IS make violent inroads into the Taliban infested area. In Snow Monkey, Gittoes paints a portrait of a Jalalabad seething with humanity, adversity and hope – focusing on three gangs of children: the Ghostbusters, persecuted Kochi boys who hawk exorcisms of bad luck and demons; the Snow Monkeys, who sell ice cream to support their families; and the Gangsters, a razor gang led by a nine-year-old antihero called Steel, terrifying to the core but still capable of experiencing aspects of the childhood seemingly taken from him. With a deeply humane vision that won him the Sydney Peace Prize, Gittoes shows us the unseen nature of Afghanistan's politics, culture and society, up close and startlingly personal. Screenings at IDFA Thurs Nov 19, 16:00 @ Tuschinski 3 (Industry Screening) Fri Nov 20, 21:45 @ Munt 10 Sat Nov 21, 17:15 @ Munt 10 Wed Nov 25, 10:30 @ Tuschinski 1 Thurs Nov 26, 18:00 @ Munt 13 Sat Nov 28, 22:00 @ EYE Cinema 1 2 SHOOTING SNOW MONKEY Members of the child gangs play with masks.