A Historical Approach to Myanmar's Democratic Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Burma's Long Road to Democracy

UNITED STATES InsTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org SPECIAL REPORT 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPORT Priscilla Clapp A career officer in the U.S. Foreign Service, Priscilla Clapp served as U.S. chargé d’affaires and chief of mission in Burma (Myanmar) from June 1999 to August 2002. After retiring from the Foreign Service, she has continued to Burma’s Long Road follow events in Burma closely and wrote a paper for the United States Institute of Peace entitled “Building Democracy in Burma,” published on the Institute’s Web site in July 2007 as Working Paper 2. In this Special to Democracy Report, the author draws heavily on her Working Paper to establish the historical context for the Saffron Revolution, explain the persistence of military rule in Burma, Summary and speculate on the country’s prospects for political transition to democracy. For more detail, particularly on • In August and September 2007, nearly twenty years after the 1988 popular uprising the task of building the institutions for stable democracy in Burma, public anger at the government’s economic policies once again spilled in Burma, see Working Paper 2 at www.usip.org. This into the country’s city streets in the form of mass protests. When tens of thousands project was directed by Eugene Martin, and sponsored by of Buddhist monks joined the protests, the military regime reacted with brute force, the Institute’s Center for Conflict Analysis and Prevention. beating, killing, and jailing thousands of people. Although the Saffron Revolution was put down, the regime still faces serious opposition and unrest. -

Burma – Myanmar

BURMA COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS Jerome Holloway 1947-1949 Vice Consul, Rangoon Edwin Webb Martin 1950-1051 Consular Officer, Rangoon Joseph A. Mendenhall 1955-1957 Economic Officer, Office of Southeast Asian Affairs, Washington DC William C. Hamilton 1957-1959 Political Officer, Rangoon Arthur W. Hummel, Jr. 1957-1961 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Rangoon Kenneth A. Guenther 1958-1959 Rangoon University, Rangoon Cliff Forster 1958-1960 Information Officer, USIS, Rangoon Morton Smith 1958-1963 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Rangoon Morton I. Abramowitz 1959 Temporary Duty, Economic Officer, Rangoon Jack Shellenberger 1959-1962 Branch Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Moulmein John R. O’Brien 1960-1962 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Rangoon Robert Mark Ward 1961 Assistant Desk Officer, USAID, Washington, DC George M. Barbis 1961-1963 Analyst for Thailand and Burma, Bureau of Intelligence and Research, Washington DC Robert S. Steven 1962-1964 Economic Officer, Rangoon Ralph J. Katrosh 1962-1965 Political Officer, Rangoon Ruth McLendon 1962-1966 Political/Consular Officer, Rangoon Henry Byroade 1963-1969 Ambassador, Burma 1 John A. Lacey 1965-1966 Burma-Cambodia Desk Officer, Washington DC Cliff Southard 1966-1969 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Rangoon Edward C. Ingraham 1967-1970 Political Counselor, Rangoon Arthur W. Hummel Jr. 1968-1971 Ambassador, Burma Robert J. Martens 1969-1970 Political – Economic Officer, Rangoon G. Eugene Martin 1969-1971 Consular Officer, Rangoon 1971-1973 Burma Desk Officer, Washington DC Edwin Webb Martin 1971-1973 Ambassador, Burma John A. Lacey 1972-1975 Deputy Chief of Mission, Rangoon James A. Klemstine 1973-1976 Thailand-Burma Desk Officer, Washington DC Frank P. Coward 1973-1978 Cultural Affairs Officer, USIS, Rangoon Richard M. -

Violent Repression in Burma: Human Rights and the Global Response

UCLA UCLA Pacific Basin Law Journal Title Violent Repression in Burma: Human Rights and the Global Response Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/05k6p059 Journal UCLA Pacific Basin Law Journal, 10(2) Author Guyon, Rudy Publication Date 1992 DOI 10.5070/P8102021999 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California COMMENTS VIOLENT REPRESSION IN BURMA: HUMAN RIGHTS AND THE GLOBAL RESPONSE Rudy Guyont TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................ 410 I. SLORC AND THE REPRESSION OF THE DEMOCRACY MOVEMENT ....................... 412 A. Burma: A Troubled History ..................... 412 B. The Pro-Democracy Rebellion and the Coup to Restore Military Control ......................... 414 C. Post Coup Elections and Political Repression ..... 417 D. Legalizing Repression ........................... 419 E. A Country Rife with Poverty, Drugs, and War ... 421 II. HUMAN RIGHTS ABUSES IN BURMA ........... 424 A. Murder and Summary Execution ................ 424 B. Systematic Racial Discrimination ................ 425 C. Forced Dislocations ............................. 426 D. Prolonged Arbitrary Detention .................. 426 E. Torture of Prisoners ............................. 427 F . R ape ............................................ 427 G . Portering ....................................... 428 H. Environmental Devastation ...................... 428 III. VIOLATIONS OF INTERNATIONAL LAW ....... 428 A. International Agreements of Burma .............. 429 1. The U.N. -

1. India and Myanmar: Understanding the Partnership – Sampa Kundu

MYANMAR AND SOUTH ASIA 1. India and Myanmar: Understanding the Partnership – Sampa Kundu, Institute for Defence Studies and Analysis, New Delhi, India; PhD Candidate, School of International Studies, Jawarhalal Nehru University, New Delhi, India Abstract: India’s bilateral relations with Myanmar has raised both optimism and doubts because of a number of ups and downs which portray India’s vague willingness to remain favoured by the Myanmar government and Myanmar’s calculated desire to get advantages from its giant neighbours including India. Scholars and practitioners have explained many times why both India and Myanmar need each other. Some may call it a realist politics and some may call it a fire-brigade alarm politics which implies that both of them act according to the need of the time. The objective of this paper is to explain the necessities of India and Myanmar to each other and how they respond to each other in different times. Connectivity, security, energy and economy are four major pillars of Indo- Myanmar bilateral relationship. Hence, each of these four sectors would have their due share in the proposed paper to illustrate the present dynamics of Indo-Myanmar partnerships. Factors like US, China and the regional cooperation initiatives including ASEAN and BIMSTEC are the external factors that are most likely to shape the future of the Indo-Myanmar relationships. Hence, a simultaneous effort would also be taken to explain the extent of their influence on the same. Based on available primary and secondary literature and field trips, this account will help the readers to contextualise Indo-Myanmar relationship in the light of international relations. -

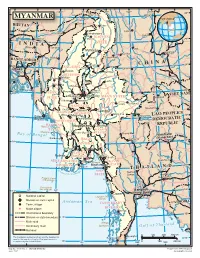

Map of Myanmar

94 96 98 J 100 102 ° ° Indian ° i ° ° 28 n ° Line s Xichang Chinese h a MYANMAR Line J MYANMAR i a n Tinsukia g BHUTAN Putao Lijiang aputra Jorhat Shingbwiyang M hm e ra k Dukou B KACHIN o Guwahati Makaw n 26 26 g ° ° INDIA STATE n Shillong Lumding i w d Dali in Myitkyina h Kunming C Baoshan BANGLADE Imphal Hopin Tengchong SH INA Bhamo C H 24° 24° SAGAING Dhaka Katha Lincang Mawlaik L Namhkam a n DIVISION c Y a uan Gejiu Kalemya n (R Falam g ed I ) Barisal r ( r Lashio M a S e w k a o a Hakha l n Shwebo w d g d e ) Chittagong y e n 22° 22° CHIN Monywa Maymyo Jinghong Sagaing Mandalay VIET NAM STATE SHAN STATE Pongsali Pakokku Myingyan Ta-kaw- Kengtung MANDALAY Muang Xai Chauk Meiktila MAGWAY Taunggyi DIVISION Möng-Pan PEOPLE'S Minbu Magway Houayxay LAO 20° 20° Sittwe (Akyab) Taungdwingyi DEMOCRATIC DIVISION y d EPUBLIC RAKHINE d R Ramree I. a Naypyitaw Loikaw w a KAYAH STATE r r Cheduba I. I Prome (Pye) STATE e Bay Chiang Mai M kong of Bengal Vientiane Sandoway (Viangchan) BAGO Lampang 18 18° ° DIVISION M a e Henzada N Bago a m YANGON P i f n n o aThaton Pathein g DIVISION f b l a u t Pa-an r G a A M Khon Kaen YEYARWARDY YangonBilugyin I. KAYIN ATE 16 16 DIVISION Mawlamyine ST ° ° Pyapon Amherst AND M THAIL o ut dy MON hs o wad Nakhon f the Irra STATE Sawan Nakhon Preparis Island Ratchasima (MYANMAR) Ye Coco Islands 92 (MYANMAR) 94 Bangkok 14° 14° ° ° Dawei (Krung Thep) National capital Launglon Bok Islands Division or state capital Andaman Sea CAMBODIA Town, village TANINTHARYI Major airport DIVISION Mergui International boundary 12° Division or state boundary 12° Main road Mergui n d Secondary road Archipelago G u l f o f T h a i l a Railroad 0 100 200 300 km Chumphon The boundaries and names shown and the designations Kawthuang 10 used on this map do not imply official endorsement or ° acceptance by the United Nations. -

Burma Road to Poverty: a Socio-Political Analysis

THE BURMA ROAD TO POVERTY: A SOCIO-POLITICAL ANALYSIS' MYA MAUNG The recent political upheavals and emergence of what I term the "killing field" in the Socialist Republic of Burma under the military dictatorship of Ne Win and his successors received feverish international attention for the brief period of July through September 1988. Most accounts of these events tended to be journalistic and failed to explain their fundamental roots. This article analyzes and explains these phenomena in terms of two basic perspec- tives: a historical analysis of how the states of political and economic devel- opment are closely interrelated, and a socio-political analysis of the impact of the Burmese Way to Socialism 2, adopted and enforced by the military regime, on the structure and functions of Burmese society. Two main hypotheses of this study are: (1) a simple transfer of ownership of resources from the private to the public sector in the name of equity and justice for all by the military autarchy does not and cannot create efficiency or elevate technology to achieve the utopian dream of economic autarky and (2) the Burmese Way to Socialism, as a policy of social change, has not produced significant and fundamental changes in the social structure, culture, and personality of traditional Burmese society to bring about modernization. In fact, the first hypothesis can be confirmed in light of the vicious circle of direct controls-evasions-controls whereby military mismanagement transformed Burma from "the Rice Bowl of Asia," into the present "Rice Hole of Asia." 3 The second hypothesis is more complex and difficult to verify, yet enough evidence suggests that the tradi- tional authoritarian personalities of the military elite and their actions have reinforced traditional barriers to economic growth. -

Fatal Silence ?

FATAL SILENCE ? Freedom of Expression and the Right to Health in Burma ARTICLE 19 July 1996 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was written by Martin Smith, a journalist and specialist writer on Burma and South East Asia. ARTICLE 19 gratefully acknowledges the support of the Open Society Institute for this publication. ARTICLE 19 would also like to acknowledge the considerable information, advice and constructive criticism supplied by very many different individuals and organisations working in the health and humanitarian fields on Burma. Such information was willingly supplied in the hope that it would increase both domestic and international understanding of the serious health problems in Burma. Under current political conditions, however, many aid workers have asked not to be identified. ©ARTICLE 19 ISBN 1 870798139 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be photocopied, recorded or otherwise reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any electronic or technical means without prior permission of the copyright owner and publisher. Note by the editor of this Internet version This version is a conversion to html of a Word document - in the Library at http://www.ibiblio.org/obl/docs/FATAL- SILENCE.doc - derived from a scan of the 1996 hard copy. The footnotes, which in the original were numbered from 1 to __ at the end of each chapter, are now placed at the end of the document, and number 1-207. The footnote references to earlier footnotes have been changed accordingly. In addition, where online versions exist of the documents referred to in the notes and bibliography, the web addresses are given, which was not the case in the original. -

Experiences of Vietnam in FDI Promotion: Some Lessons for Myanmar

CHAPTER 4 Experiences of Vietnam in FDI Promotion: Some Lessons for Myanmar Thanh Tri VO and Duong Anh NGUYEN This chapter should be cited as: Vo, T T and Nguyen, A D., 2012. “Experiences of Vietnam in FDI Promotion: Some Lessons for Myanmar.” In Economic Reforms in Myanmar: Pathways and Prospects, edited by Hank Lim and Yasuhiro Yamada, BRC Research Report No.10, Bangkok Research Center, IDE-JETRO, Bangkok, Thailand. Chapter 4 Experiences of Vietnam in FDI Promotion: Some Lessons for Myanmar Thanh Tri VO, Duong Anh NGUYEN ______________________________________________________________________ Abstract Since 1986, Vietnam has carried out various measures to attract foreign direct investment (FDI), in line with deepened integration into the regional and world economies. The legal framework for FDI entry into the country has improved since 1987, with the promulgation of and numerous amendments to the Foreign Investment Law, alongside other legal-economic reforms concerning trading rights, the tarification of non-tariff barriers, etc. These structural and procedural changes facilitated FDI inflows to Vietnam, though such inflows varied during different periods. There are, however, some concerns about the effectiveness of recent FDI inflows, particularly regarding the low ratio of implemented capital over registered capital, and the State’s limited ability to manage capital inflows. Vietnam also took some practical steps, and experienced a string of success, in various aspects of FDI promotion – such as the introduction of export processing zones and industrial zones, the supply of infrastructure facilities, the delegation of FDI management authority to local governments, and the dialogue mechanism with the Government of Japan to support FDI operations. -

Burmese Students Seek Arms

ERG- 20 NOT FOR PUBLICATION WITHOUT WRITER'S CONSENT INSTITUTE OF CURRENT WORLD AFFAIRS Bangkok October, 1988 "An Idea Plus a Bayonet'" Burmese Students Seek Arms My second attempt to enter Burma, this time through the back door on the southern Thai border, was halted by a sudden high fever.. Thus, this report on the Burmese student movement comes to you after a quinine-induced haze. In the aftermath of the bloody September 18 coup by Gen. Saw Maung, well over 3,000 students have fled Rangoon and other cities for the Thai border, seeking arms and refuge. Student leaders on the Thai-Burmese border say that peaceful protests alone, especially the type advocated by the elderly opposition leaders in Rangoon, are doomed to fail.. One soft-spoken student said of the opposition leaders in Rangoon, "They have ideas but no guns. Revolution equals an idea plus a bayonet." Maung Maung Thein, a stocky Rangoon University student, led 74 other students out of Rangoon on September 7, eleven days before the coup. Convinced that armed struggle was the only way to overthrow the regime, they traveled over 700 miles down the Burmese coast by passenger bus, boat, and on foot. Sometimes they moved at night to avoid Army checkpoints. But this was during the heady days before the coup when one opposi- tion leader, Aung Gyi, predicted that the government would fall in a matter of weeks. Crowds of people welcomed the students, presenting them with rice and curry. As one student described it, "They were clapping. Some of the women called us their sons. -

Myanmar/Bangladesh Repatriation and Reintegration Operation

PROG IAL RAM EC M SP E MYANMAR/BANGLADESH REPATRIATION AND REINTEGRATION OPERATION AT A GLANCE Main Objectives and Activities Bangladesh Protect and assist 22,000 refugees remaining in the camps; facilitate their repatriation to Myanmar while ensuring the voluntary nature of returns; and promote interim solutions for those remaining refugees unable or unwilling to return by encouraging self-sufficiency activities. Myanmar Continue to work with the Government on the successful rein- tegration of returnees; promote the stabilisation of the pop- ulation of Northern Rakhine State through multi-sectoral assis- tance and monitoring in areas hosting returnees. The establishment of a UN Integrated Development Plan in Northern Rakhine State continued to be a key factor in UNHCR’s strategy to phase down its assistance activities throughout 2000. Impact • In Bangladesh, only 1,130 refugees were repatriated dur- ing 1999 because of procedural difficulties in obtaining clearance for those scheduled to return to Myanmar. Some 22,000 refugees remained in the camps, dependent on external assistance. • No major population movement to Bangladesh has been reported since mid-1997. This can be attributed to UNHCR’s continued monitoring and protection activ- ities, combined with an extensive assistance programme which contributed to the stability of the population in Persons of Concern Northern Rakhine State. HOST COUNTRY/ TOTAL IN OF WHICH: PER CENT PER CENT TYPE OF POPULATION COUNTRY UNHCR-ASSISTED FEMALE < 18 • The situation of women and children in the refugee Bangladesh (Refugees) 22,000 22,000 51 60 camps was improved by integrating protection and assis- Myanmar (Returned in 1999)* 1,130 1,130 50 - tance concerns through increased participation in camp * During 1998, 100 Myanmar refugees returned. -

A Study of Myanmar-US Relations

INDEX A strike at Hi-Mo factory and, 146, “A Study of Myanmar-US Relations”, 147 294 All Burma Students’ Democratic abortion, 318, 319 Front, 113, 125, 130 n.6 accountability, 5, 76 All India Radio, 94, 95, 96, 99 financial management and, 167 All Mon Regional Democracy Party, administrative divisions of Myanmar, 104, 254 n.4 170, 176 n.12 allowances for workers, 140–41, 321 Africa, 261 American Centre, 118 African National Congress, 253 n.2 American Jewish World Service, 131 Agarwal, B., 308 n.7 “agency” of individuals, 307 Amyotha Hluttaw (upper house of Agricultural Census of Myanmar parliament), 46, 243, 251 (1993), 307 Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom Agricultural Ministers in States and League, 23 Regions, 171 Anwar, Mohammed, 343 n.1 agriculture, 190ff ANZ Bank (Australia), 188 loans for, 84 “Arab Spring”, 28, 29, 138 organizational framework of, “arbitrator [regime]”, 277 192, 193 Armed Forces Day 2012, 270 Ah-Yee-Taung, 309 armed forces (of Myanmar), 22, 23, aid, 295, 315 262, 269, 277, 333, 334 donors and, 127, 128 battalions 437 and 348, 288 Kachin people and, 293, 295 border areas and, 24 Alagappa, Muthiah, 261, 263, 264 constitution and, 16, 20, 24, 63, Albert Einstein Institution, 131 n.7 211, 265, 266 All Burma Federation of Student corruption and, 26, 139–40 Unions, 115, 121–22, 130 n.4, 130 disengagement from politics, 259 n.6, 148 expenditure, 62, 161, 165, 166 “fifth estate”, 270 356 Index “four cuts” strategy, 288, 293 Aung Kyaw Hla, 301 n.5 impunity and, 212, 290 Aung Ko, 60 Kachin State and, 165, 288, 293 Aung Min, 34, -

ASA 16/06/93 £Myanmar @The Climate of Fear Continues, Members of Ethnic Minorities and Political Prisoners Still Targ

AI Index: ASA 16/06/93 £Myanmar @The climate of fear continues, members of ethnic minorities and political prisoners still targeted August 1993 captions: Pro-democracy demonstrators in Mandalay, Myanmar's second city, protest against 26 years of one-party military rule in 1988. Burmese monks demonstrate outside the Myanmar Embassy in Bangkok. Mohamed Ilyas, a Burmese Muslim from the Rakhine State, was believed to have been tortured to death in June 1992 by Military Intelligence personnel. The Salween River, which marks the border between Myanmar and Thailand. Karen women in a refugee camp in Thailand. A former porter who was found unconscious in the jungle, abandoned by troops and covered with sores infested with maggots. Karen children in a refugee camp in Thailand. A woman who had been raped by the tatmadaw. 1. INTRODUCTION The State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC), Myanmar's military rulers, continues to commit grave human rights violations against the Burmese people with impunity. Members of political opposition parties and ethnic minorities alike live in an atmosphere of fear which pervades all areas of the country. Some improvements have been made in the human rights situation, but the SLORC has not instituted more fundamental changes which would provide the population of Myanmar with protection from ongoing and systematic violations of human rights. Amnesty International welcomes these limited improvements, but it believes that the degree and scope of human rights violations in Myanmar continue to warrant serious international concern. In the material which follows, Amnesty International's concerns in the period from September 1992 until July 1993 are described in detail.