Experiences of Vietnam in FDI Promotion: Some Lessons for Myanmar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Burma's Long Road to Democracy

UNITED STATES InsTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org SPECIAL REPORT 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPORT Priscilla Clapp A career officer in the U.S. Foreign Service, Priscilla Clapp served as U.S. chargé d’affaires and chief of mission in Burma (Myanmar) from June 1999 to August 2002. After retiring from the Foreign Service, she has continued to Burma’s Long Road follow events in Burma closely and wrote a paper for the United States Institute of Peace entitled “Building Democracy in Burma,” published on the Institute’s Web site in July 2007 as Working Paper 2. In this Special to Democracy Report, the author draws heavily on her Working Paper to establish the historical context for the Saffron Revolution, explain the persistence of military rule in Burma, Summary and speculate on the country’s prospects for political transition to democracy. For more detail, particularly on • In August and September 2007, nearly twenty years after the 1988 popular uprising the task of building the institutions for stable democracy in Burma, public anger at the government’s economic policies once again spilled in Burma, see Working Paper 2 at www.usip.org. This into the country’s city streets in the form of mass protests. When tens of thousands project was directed by Eugene Martin, and sponsored by of Buddhist monks joined the protests, the military regime reacted with brute force, the Institute’s Center for Conflict Analysis and Prevention. beating, killing, and jailing thousands of people. Although the Saffron Revolution was put down, the regime still faces serious opposition and unrest. -

1. India and Myanmar: Understanding the Partnership – Sampa Kundu

MYANMAR AND SOUTH ASIA 1. India and Myanmar: Understanding the Partnership – Sampa Kundu, Institute for Defence Studies and Analysis, New Delhi, India; PhD Candidate, School of International Studies, Jawarhalal Nehru University, New Delhi, India Abstract: India’s bilateral relations with Myanmar has raised both optimism and doubts because of a number of ups and downs which portray India’s vague willingness to remain favoured by the Myanmar government and Myanmar’s calculated desire to get advantages from its giant neighbours including India. Scholars and practitioners have explained many times why both India and Myanmar need each other. Some may call it a realist politics and some may call it a fire-brigade alarm politics which implies that both of them act according to the need of the time. The objective of this paper is to explain the necessities of India and Myanmar to each other and how they respond to each other in different times. Connectivity, security, energy and economy are four major pillars of Indo- Myanmar bilateral relationship. Hence, each of these four sectors would have their due share in the proposed paper to illustrate the present dynamics of Indo-Myanmar partnerships. Factors like US, China and the regional cooperation initiatives including ASEAN and BIMSTEC are the external factors that are most likely to shape the future of the Indo-Myanmar relationships. Hence, a simultaneous effort would also be taken to explain the extent of their influence on the same. Based on available primary and secondary literature and field trips, this account will help the readers to contextualise Indo-Myanmar relationship in the light of international relations. -

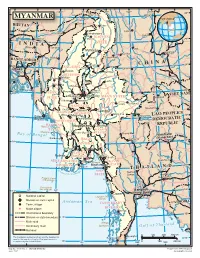

Map of Myanmar

94 96 98 J 100 102 ° ° Indian ° i ° ° 28 n ° Line s Xichang Chinese h a MYANMAR Line J MYANMAR i a n Tinsukia g BHUTAN Putao Lijiang aputra Jorhat Shingbwiyang M hm e ra k Dukou B KACHIN o Guwahati Makaw n 26 26 g ° ° INDIA STATE n Shillong Lumding i w d Dali in Myitkyina h Kunming C Baoshan BANGLADE Imphal Hopin Tengchong SH INA Bhamo C H 24° 24° SAGAING Dhaka Katha Lincang Mawlaik L Namhkam a n DIVISION c Y a uan Gejiu Kalemya n (R Falam g ed I ) Barisal r ( r Lashio M a S e w k a o a Hakha l n Shwebo w d g d e ) Chittagong y e n 22° 22° CHIN Monywa Maymyo Jinghong Sagaing Mandalay VIET NAM STATE SHAN STATE Pongsali Pakokku Myingyan Ta-kaw- Kengtung MANDALAY Muang Xai Chauk Meiktila MAGWAY Taunggyi DIVISION Möng-Pan PEOPLE'S Minbu Magway Houayxay LAO 20° 20° Sittwe (Akyab) Taungdwingyi DEMOCRATIC DIVISION y d EPUBLIC RAKHINE d R Ramree I. a Naypyitaw Loikaw w a KAYAH STATE r r Cheduba I. I Prome (Pye) STATE e Bay Chiang Mai M kong of Bengal Vientiane Sandoway (Viangchan) BAGO Lampang 18 18° ° DIVISION M a e Henzada N Bago a m YANGON P i f n n o aThaton Pathein g DIVISION f b l a u t Pa-an r G a A M Khon Kaen YEYARWARDY YangonBilugyin I. KAYIN ATE 16 16 DIVISION Mawlamyine ST ° ° Pyapon Amherst AND M THAIL o ut dy MON hs o wad Nakhon f the Irra STATE Sawan Nakhon Preparis Island Ratchasima (MYANMAR) Ye Coco Islands 92 (MYANMAR) 94 Bangkok 14° 14° ° ° Dawei (Krung Thep) National capital Launglon Bok Islands Division or state capital Andaman Sea CAMBODIA Town, village TANINTHARYI Major airport DIVISION Mergui International boundary 12° Division or state boundary 12° Main road Mergui n d Secondary road Archipelago G u l f o f T h a i l a Railroad 0 100 200 300 km Chumphon The boundaries and names shown and the designations Kawthuang 10 used on this map do not imply official endorsement or ° acceptance by the United Nations. -

Myanmar/Bangladesh Repatriation and Reintegration Operation

PROG IAL RAM EC M SP E MYANMAR/BANGLADESH REPATRIATION AND REINTEGRATION OPERATION AT A GLANCE Main Objectives and Activities Bangladesh Protect and assist 22,000 refugees remaining in the camps; facilitate their repatriation to Myanmar while ensuring the voluntary nature of returns; and promote interim solutions for those remaining refugees unable or unwilling to return by encouraging self-sufficiency activities. Myanmar Continue to work with the Government on the successful rein- tegration of returnees; promote the stabilisation of the pop- ulation of Northern Rakhine State through multi-sectoral assis- tance and monitoring in areas hosting returnees. The establishment of a UN Integrated Development Plan in Northern Rakhine State continued to be a key factor in UNHCR’s strategy to phase down its assistance activities throughout 2000. Impact • In Bangladesh, only 1,130 refugees were repatriated dur- ing 1999 because of procedural difficulties in obtaining clearance for those scheduled to return to Myanmar. Some 22,000 refugees remained in the camps, dependent on external assistance. • No major population movement to Bangladesh has been reported since mid-1997. This can be attributed to UNHCR’s continued monitoring and protection activ- ities, combined with an extensive assistance programme which contributed to the stability of the population in Persons of Concern Northern Rakhine State. HOST COUNTRY/ TOTAL IN OF WHICH: PER CENT PER CENT TYPE OF POPULATION COUNTRY UNHCR-ASSISTED FEMALE < 18 • The situation of women and children in the refugee Bangladesh (Refugees) 22,000 22,000 51 60 camps was improved by integrating protection and assis- Myanmar (Returned in 1999)* 1,130 1,130 50 - tance concerns through increased participation in camp * During 1998, 100 Myanmar refugees returned. -

Report of Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar

A/HRC/39/64 Advance Edited Version Distr.: General 12 September 2018 Original: English Human Rights Council Thirty-ninth session 10–28 September 2018 Agenda item 4 Human rights situations that require the Council’s attention Report of the independent international fact-finding mission on Myanmar* Summary The Human Rights Council established the independent international fact-finding mission on Myanmar in its resolution 34/22. In accordance with its mandate, the mission focused on the situation in Kachin, Rakhine and Shan States since 2011. It also examined the infringement of fundamental freedoms, including the rights to freedom of expression, assembly and peaceful association, and the question of hate speech. The mission established consistent patterns of serious human rights violations and abuses in Kachin, Rakhine and Shan States, in addition to serious violations of international humanitarian law. These are principally committed by the Myanmar security forces, particularly the military. Their operations are based on policies, tactics and conduct that consistently fail to respect international law, including by deliberately targeting civilians. Many violations amount to the gravest crimes under international law. In the light of the pervasive culture of impunity at the domestic level, the mission finds that the impetus for accountability must come from the international community. It makes concrete recommendations to that end, including that named senior generals of the Myanmar military should be investigated and prosecuted in an international criminal tribunal for genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes. * The present report was submitted after the deadline in order to reflect the most recent developments. A/HRC/39/64 Contents Page I. -

Myanmar Maneuvers How to Break Political-Criminal Alliances in Contexts of Transition

United Nations University Centre for Policy Research Crime-Conflict Nexus Series: No 9 April 2017 Myanmar Maneuvers How to Break Political-Criminal Alliances in Contexts of Transition Dr. Vanda Felbab-Brown Senior Fellow, The Brookings Institution This material has been funded by UK aid from the UK government; however the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies. © 2017 United Nations University. All Rights Reserved. ISBN 978-92-808-9040-2 Myanmar Maneuvers How to Break Political-Criminal Alliances in Contexts of Transition 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Myanmar case study analyzes the complex interactions between illegal economies -conflict and peace. Particular em- phasis is placed on understanding the effects of illegal economies on Myanmar’s political transitions since the early 1990s, including the current period, up through the first year of the administration of Aung San Suu Kyi. Described is the evolu- tion of illegal economies in drugs, logging, wildlife trafficking, and gems and minerals as well as land grabbing and crony capitalism, showing how they shaped and were shaped by various political transitions. Also examined was the impact of geopolitics and the regional environment, particularly the role of China, both in shaping domestic political developments in Myanmar and dynamics within illicit economies. For decades, Burma has been one of the world’s epicenters of opiate and methamphetamine production. Cultivation of poppy and production of opium have coincided with five decades of complex and fragmented civil war and counterinsur- gency policies. An early 1990s laissez-faire policy of allowing the insurgencies in designated semi-autonomous regions to trade any products – including drugs, timber, jade, and wildlife -- enabled conflict to subside. -

Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses

Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses www.rsis.edu.sg ISSN 2382-6444 | Volume 11, Issue 3 | March 2019 A JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR POLITICAL VIOLENCE AND TERRORISM RESEARCH (ICPVTR) Buddhist Extremism in Sri Lanka and Myanmar: An Examination Amresh Gunasingham Leadership Decapitation and the Impact on Terrorist Groups Kenneth Yeo Yaoren Denmark’s De-Radicalisation Programme for Returning Foreign Terrorist Fighters Ahmad Saiful Rijal Bin Hassan Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses Volume 9, Issue 4 | April 2017 1 Building a Global Network for Security Editorial Note March Issue The discourse on religious extremism in the decapitation on four key groups: Hamas, past few decades has largely been dominated Hezbollah, Abu Sayyaf Group and Jemaah by Islamist-oriented trends and actors. Islamiyah in terms of the frequency and However, there are emerging alternate lethality of attacks after the arrests or killings of discourses of religious extremism that are their leaders are observed. It is argued that, becoming relevant in South and Southeast “leadership decapitation is not a silver bullet Asia – Buddhist and Hindu extremism. The against terrorism”, necessitating broader March Issue thus focuses on Sri Lanka and responses to counter the ideology and Myanmar as case studies depicting the rise of operational strength of religiously-motivated Buddhist extremism and related intolerance terrorist groups. towards the minority Muslim communities. The Issue also delves into two different responses Lastly, Ahmad Saiful Rijal Bin Hassan focuses Wto counter -terrorism by the state and on Denmark’s de-radicalisation programme in community stakeholders in their bid to tackle light of the returning foreign terrorist fighters religious-motivated terrorist groups. -

Market & Country Brief on Myanmar (Burma)

SRI LANKA EXPORT DEVELOPMENT BOARD Market & Country brief on Myanmar (Burma) PREPARED BY MARKET DEVELOPMENT DIVISION-EDB October, 2018 Contents 1. Myanmar in Brief 2. Trade between Sri Lanka and Myanmar 3. Bilateral Trade between Sri Lanka and Myanmar (2013-2017) 4. Sri Lanka’s Major Export Products to Myanmar (2013-2017) 5. Sri Lanka’s Major Import Products from Myanmar (2013-2017) 6. Sri Lanka’s Leading Exporters to Myanmar -2017 7. Potential Exports to Myanmar from Sri Lanka 8. Myanmar Trade with the World (2013-2017) 9. Trade Agreements of Myanmar 10. Useful Addresses 2 | P a g e 1. Myanmar in Brief Geographical Location Myanmar – Map Myanmar - Flag Myanmar is a country in Southeastern Asia that covers an area of 676,578 square kilometers and the 41st largest country in the world. Myanmar is bordered by the Andaman Sea and the Bay of Bengal, between Bangladesh and Thailand. The capital of Myanmar is Rangoon. The country possess petroleum, timber, tin, antimony, zinc, copper, tungsten, lead, coal, marble, limestone, precious stones, natural gas, hydropower and arable land as natural resources. Demography Population : 55,123,814 (July 2017 est.) Population growth rate : 0.91% (2017 est.) 3 | P a g e Economy Burma’s economic growth rate recovered from a low growth under 6% in 2011 but has been volatile between 6% and 7.2% during the past few years. Burma’s abundant natural resources and young labor force have the potential to attract foreign investment in the energy, garment, information technology, and food and beverage sectors. The government is focusing on accelerating agricultural productivity and land reforms, modernizing and opening the financial sector, and developing transportation and electricity infrastructure. -

Myanmar: Ethnic Politics and the 2020 General Election

MYANMAR POLICY BRIEFING | 23 | September 2020 Myanmar: Ethnic Politics and the 2020 General Election KEY POINTS • The 2020 general election is scheduled to take place at a critical moment in Myanmar’s transition from half a century under military rule. The advent of the National League for Democracy to government office in March 2016 was greeted by all the country’s peoples as the opportunity to bring about real change. But since this time, the ethnic peace process has faltered, constitutional reform has not started, and conflict has escalated in several parts of the country, becoming emergencies of grave international concern. • Covid-19 represents a new – and serious – challenge to the conduct of free and fair elections. Postponements cannot be ruled out. But the spread of the pandemic is not expected to have a significant impact on the election outcome as long as it goes ahead within constitutionally-appointed times. The NLD is still widely predicted to win, albeit on reduced scale. Questions, however, will remain about the credibility of the polls during a time of unprecedented restrictions and health crisis. • There are three main reasons to expect NLD victory. Under the country’s complex political system, the mainstream party among the ethnic Bamar majority always win the polls. In the population at large, a victory for the NLD is regarded as the most likely way to prevent a return to military government. The Covid-19 crisis and campaign restrictions hand all the political advantages to the NLD and incumbent authorities. ideas into movement • To improve election performance, ethnic nationality parties are introducing a number of new measures, including “party mergers” and “no-compete” agreements. -

Crossing the Line: Geopolitics and Criminality at the India-Myanmar Border

RESEARCH REPORT CROSSING THE LINE Geopolitics and criminality at the India–Myanmar border PREM MAHADEVAN NOVEMBER 2020 CROSSING THE LINE CROSSING THE LINE Geopolitics and criminality at the India–Myanmar border ww Prem Mahadevan November 2020 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to thank Mark Shaw and Tuesday Reitano for invaluable feedback provided during the course of this research project. Thanks also to Mark Ronan and his team for a speedy and efficient editorial process. The author expresses gratitude to the Government of Norway for funding the research. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Before joining the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, Prem Mahadevan was a senior researcher with the Center for Security Studies at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology. He specialized in research on organized crime, intelligence and irregular warfare. He has co-authored policy studies for the Swiss foreign ministry and written a book on counter-terrorist operations for the Indian Army. His academic publications include two books on intelligence and terrorism. © 2020 Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Global Initiative. Cover: View of the remote Zokhawthar–Rihkhawdar border crossing, a hotspot for the illicit smuggling of goods between India and Myanmar. © Eric Winny via Wikimedia Commons Design: Elné Potgieter Cartography: Rudi de Lange Please direct inquiries to: -

View on Myanmar/Burma

Uniya JESUIT SOCIAL JUSTICE CENTRE VIEW ON ASIA briefing series MYANMAR/BURMA Union of Myanmar (Burma) Capital: Yangon (Rangoon) Head of state: Sen. General Than Shwe Border countries: Thailand, Laos, China, India, Bangladesh India KACHIN Myanmar/Burma 1 has had a spurt of foreign relations controversies ever since it abruptly Bangla- China adjourned its controversial 2004 National desh CHIN Convention to draft a new constitution. In Mandalay August 2004, Myanmar/Burma was hit by SHAN Vietnam RAKHINE renewed sanctions from the US, faced being Laos banned from the upcoming Asia-Europe Meeting Yangon KAREN (ASEM) and its officials were barred from the 28th Olympic Games in Athens for its lack of MON Thailand human rights and democracy – a reminder that Myanmar/Burma still remains one of the most Cambodia difficult foreign policy challenges in Asia for the international community. Myanmar/Burma is situated east of the Andaman Sea and strategically buffers the world’s two Malaysia largest populations, China and India. The 1 Since 1989 the authorities have promoted the name Myanmar instead of Burma as a conventional name for their state. The name change is recognised by the UN but not the US. Australia does not seem to have an official position on the choice of terminology. Burmese expatriates, including those residing in Australia, continue to use the old colonial name. This paper uses both names, attaching no political significance to either term. Released: September 2004 PO Box 522 Kings Cross NSW 1340 Australia Author: Minh Nguyen Tel (02) 9356 3888 Fax (02) 9356 3021 Web www.uniya.org Em [email protected] VIEW ON ASIA Myanmar/Burma 2 country is rich in resources and diverse in the lower Myanmar/Burma region; the its ethnic demography. -

Interpreting Myanmar a Decade of Analysis

INTERPRETING MYANMAR A DECADE OF ANALYSIS INTERPRETING MYANMAR A DECADE OF ANALYSIS ANDREW SELTH Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760464042 ISBN (online): 9781760464059 WorldCat (print): 1224563457 WorldCat (online): 1224563308 DOI: 10.22459/IM.2020 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover photograph: Yangon, Myanmar by mathes on Bigstock. This edition © 2020 ANU Press CONTENTS Acronyms and abbreviations . xi Glossary . xv Acknowledgements . xvii About the author . xix Protocols and politics . xxi Introduction . 1 THE INTERPRETER POSTS, 2008–2019 2008 1 . Burma: The limits of international action (12:48 AEDT, 7 April 2008) . 13 2 . A storm of protest over Burma (14:47 AEDT, 9 May 2008) . 17 3 . Burma’s continuing fear of invasion (11:09 AEDT, 28 May 2008) . 21 4 . Burma’s armed forces: How loyal? (11:08 AEDT, 6 June 2008) . 25 5 . The Rambo approach to Burma (10:37 AEDT, 20 June 2008) . 29 6 . Burma and the Bush White House (10:11 AEDT, 26 August 2008) . 33 7 . Burma’s opposition movement: A house divided (07:43 AEDT, 25 November 2008) . 37 2009 8 . Is there a Burma–North Korea–Iran nuclear conspiracy? (07:26 AEDT, 25 February 2009) . 43 9 . US–Burma: Where to from here? (14:09 AEDT, 28 April 2009) .