Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of Buddhist-Muslim Conflict in Asia and Possibilities for Transformation by Iselin Frydenlund

Policy Brief December 2015 The rise of Buddhist-Muslim conflict in Asia and possibilities for transformation By Iselin Frydenlund Executive summary Violence against Muslim minorities in Buddhist societies has increased in recent years. The Muslim Rohingyas in Myanmar are disenfranchised, and many of their candidates were rejected by the official Union Election Commission prior to the 2015 elections. Furthermore laws about religious conversion, missionary activities, and interfaith marriage are being pro- moted to control relations between religions and prevent conflict. The danger, however, is that increased control will lead to more, not fewer, conflicts. Discrimination against religious minorities may lead to radicalisation. In addition minority-majority relations in a single state may have regional consequences because a minority in one state can be the majority in another, and there is an increasing trend for co-religionists in different countries to support each other. Thus protection of religious minorities is not only a question of freedom of religion and basic human rights; it also affects security and peacebuilding in the whole region. Anti- Muslim violence and political exclusion of Muslim minorities take place in the wake of in- creased Buddhist nationalism. This policy brief identifies local as well as global drivers for Buddhist-Muslim conflict and the rise of Buddhist nationalism. It then shows how Buddhist- Muslim conflict can be addressed, most importantly through the engagement of local religious leaders. Introduction Buddhist countries are generally at risk of persecution. But Attacks on Muslim minorities in Buddhist countries have weak state protection of Muslim communities leaves these escalated in recent years (OHCHR, 2014). -

Burma's Long Road to Democracy

UNITED STATES InsTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org SPECIAL REPORT 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPORT Priscilla Clapp A career officer in the U.S. Foreign Service, Priscilla Clapp served as U.S. chargé d’affaires and chief of mission in Burma (Myanmar) from June 1999 to August 2002. After retiring from the Foreign Service, she has continued to Burma’s Long Road follow events in Burma closely and wrote a paper for the United States Institute of Peace entitled “Building Democracy in Burma,” published on the Institute’s Web site in July 2007 as Working Paper 2. In this Special to Democracy Report, the author draws heavily on her Working Paper to establish the historical context for the Saffron Revolution, explain the persistence of military rule in Burma, Summary and speculate on the country’s prospects for political transition to democracy. For more detail, particularly on • In August and September 2007, nearly twenty years after the 1988 popular uprising the task of building the institutions for stable democracy in Burma, public anger at the government’s economic policies once again spilled in Burma, see Working Paper 2 at www.usip.org. This into the country’s city streets in the form of mass protests. When tens of thousands project was directed by Eugene Martin, and sponsored by of Buddhist monks joined the protests, the military regime reacted with brute force, the Institute’s Center for Conflict Analysis and Prevention. beating, killing, and jailing thousands of people. Although the Saffron Revolution was put down, the regime still faces serious opposition and unrest. -

Myanmar Buddhism of the Pagan Period

MYANMAR BUDDHISM OF THE PAGAN PERIOD (AD 1000-1300) BY WIN THAN TUN (MA, Mandalay University) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAMME NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2002 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to the people who have contributed to the successful completion of this thesis. First of all, I wish to express my gratitude to the National University of Singapore which offered me a 3-year scholarship for this study. I wish to express my indebtedness to Professor Than Tun. Although I have never been his student, I was taught with his book on Old Myanmar (Khet-hoà: Mranmâ Râjawaà), and I learnt a lot from my discussions with him; and, therefore, I regard him as one of my teachers. I am also greatly indebted to my Sayas Dr. Myo Myint and Professor Han Tint, and friends U Ni Tut, U Yaw Han Tun and U Soe Kyaw Thu of Mandalay University for helping me with the sources I needed. I also owe my gratitude to U Win Maung (Tampavatî) (who let me use his collection of photos and negatives), U Zin Moe (who assisted me in making a raw map of Pagan), Bob Hudson (who provided me with some unpublished data on the monuments of Pagan), and David Kyle Latinis for his kind suggestions on writing my early chapters. I’m greatly indebted to Cho Cho (Centre for Advanced Studies in Architecture, NUS) for providing me with some of the drawings: figures 2, 22, 25, 26 and 38. -

The Role of Buddhism in the Changing Life of Rural Women in Sri Lanka Since Independence

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 1-1-2002 The role of Buddhism in the changing life of rural women in Sri Lanka since independence Lalani Weddikkara Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Weddikkara, L. (2002). The role of Buddhism in the changing life of rural women in Sri Lanka since independence. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/746 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/746 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. -

What About the Rohingya?

UPPSALA UNIVERSITY Department of Theology Master Programme in Religion in Peace and Conflict Master thesis, 30 credits Spring, 2019 Supervisor: Håkan Bengtsson What about the Rohingya? A study searching for power relations in different levels of society Ewa Einarsson Abstract This study aims to search for patterns that demonstrate power relations. It specifically seeks to identify patterns in the power relations in the Rohingya conflict and understand the established power relations at different levels in society, which could provide a picture of the social world within the context of historical, ethnic, cultural, religious and political circumstances. Moreover, this study illustrates the Rohingya population’s experience with relations of power. The ongoing conflict in Myanmar, which is based on religion, ethnicity and politics, is seemingly without any solution. Myanmar is depicted as a country that has lost both hope and legitimacy for the political system and has reduced chances to establish a society in which all the minorities are included across the spheres of society. Finding a bright future for the Rohingya population might be difficult; nevertheless, this study seeks to enhance the understanding of the ongoing conflict and the underlying power relations. 2 Table of Contents A study searching for power relations in different levels of society ................................................................. 1 ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................... -

The Interface Between Buddhism and International Humanitarian Law (Ihl)

REDUCING SUFFERING DURING CONFLICT: THE INTERFACE BETWEEN BUDDHISM AND INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW (IHL) Exploratory position paper as background for 4th to 6th September 2019 conference in Dambulla, Sri Lanka Peter Harvey (University of Sunderland, Emeritus), with: Kate Crosby (King’s College, London), Mahinda Deegalle (Bath Spa University), Elizabeth Harris (University of Birmingham), Sunil Kariyakarawana (Buddhist Chaplain to Her Majesty’s Armed Forces), Pyi Kyaw (King’s College, London), P.D. Premasiri (University of Peradeniya, Emeritus), Asanga Tilakaratne (University of Colombo, Emeritus), Stefania Travagnin (University of Groningen). Andrew Bartles-Smith (International Committee of the Red Cross). Though he should conquer a thousand men in the battlefield, yet he, indeed, is the nobler victor who should conquer himself. Dhammapada v.103 AIMS AND RATIONALE OF THE CONFERENCE This conference, organized by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) in collaboration with a number of universities and organizations, will explore correspondences between Buddhism and IHL and encourage a constructive dialogue and exchange between the two domains. The conference will act as a springboard to understanding how Buddhism can contribute to regulating armed conflict, and what it offers in terms of guidance on the conduct of, and behavior during, war for Buddhist monks and lay persons – the latter including government and military personnel, non-State armed groups and civilians. The conference is concerned with the conduct of armed conflict, and not with the reasons and justifications for it, which fall outside the remit of IHL. In addition to exploring correspondences between IHL and Buddhist ethics, the conference will also explore how Buddhist combatants and communities understand IHL, and where it might align with Buddhist doctrines and practices: similarly, how their experience of armed conflict might be drawn upon to better promote IHL and Buddhist principles, thereby improving conduct of hostilities on the ground. -

Buddhism Transformed: Religious Change in Sri Lanka (Richard

THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BUDDHIST STUDIES EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Roger Jackson Dept. of Religion Carleton College Northfield, MN 55057 USA EDITORS Peter N. Gregory Ernst Steinkellner University of Illinois University of Vienna Urbana-Champaign, Illinois, USA Wien, Austria Alexander W. Macdonald Jikido Takasaki University de Paris X University of Tokyo Nanterre, France Tokyo, Japan Steven Collins Robert Thurman Concordia University Columbia University Montreal, Canada New York, New York, USA Volume 13 1990 Number 2 CONTENTS I. ARTICLES 1. A Lajja Gaurl in a Buddhist Context at Aurangabad by Robert L. Brown 1 2. Sa-skya Pandita the "Polemicist": Ancient Debates and Modern Interpretations by David Jackson 17 3. Vajrayana Deities in an Illustrated Indian Manuscript of the Astasahasrika-prajhaparamita by John Newman 117 4. The Mantra "Om mani-padme hum" in an Early Tibetan Grammatical Treatise byP.C. Verhagen 133 II. BOOK REVIEWS 1. Buddhism Transformed: Religious Change in Sri Lanka, by Richard Gombrich and Gananath Obeyesekere (Vijitha Rajapakse) 139 2. The Emptiness of Emptiness: An Introduction to Early Indian Madhyamika, by C. W. Huntington, Jr., with Geshe Namgyal Wangchen (Jose Ignacio Cabezon) 152 III. NOTES AND NEWS 1. Notice of The Buddhist Forum (Roger Jackson) 163 ERRATA 164 LIST OF CONTRIBUTORS 165 II. Book Reviews Buddhism Transformed: Religious Change in Sri Lanka, by Richard Gombrich and Gananath Obeyesekere. Princeton: Princeton Uni versity Press, 1988, pp. xvi, 484. Recent social scientific investigations of Theravada practice in South and Southeast Asian countries may have not only brought to the fore interesting information about the character of "popular" Buddhism, but also generated intriguing analyses of the contours, range and roots of the religiosity this Buddhism encompasses. -

1. India and Myanmar: Understanding the Partnership – Sampa Kundu

MYANMAR AND SOUTH ASIA 1. India and Myanmar: Understanding the Partnership – Sampa Kundu, Institute for Defence Studies and Analysis, New Delhi, India; PhD Candidate, School of International Studies, Jawarhalal Nehru University, New Delhi, India Abstract: India’s bilateral relations with Myanmar has raised both optimism and doubts because of a number of ups and downs which portray India’s vague willingness to remain favoured by the Myanmar government and Myanmar’s calculated desire to get advantages from its giant neighbours including India. Scholars and practitioners have explained many times why both India and Myanmar need each other. Some may call it a realist politics and some may call it a fire-brigade alarm politics which implies that both of them act according to the need of the time. The objective of this paper is to explain the necessities of India and Myanmar to each other and how they respond to each other in different times. Connectivity, security, energy and economy are four major pillars of Indo- Myanmar bilateral relationship. Hence, each of these four sectors would have their due share in the proposed paper to illustrate the present dynamics of Indo-Myanmar partnerships. Factors like US, China and the regional cooperation initiatives including ASEAN and BIMSTEC are the external factors that are most likely to shape the future of the Indo-Myanmar relationships. Hence, a simultaneous effort would also be taken to explain the extent of their influence on the same. Based on available primary and secondary literature and field trips, this account will help the readers to contextualise Indo-Myanmar relationship in the light of international relations. -

Stephen Carl Berkwitz

STEPHEN CARL BERKWITZ Department of Religious Studies Missouri State University 901 S. National Ave. Springfield, MO 65897 (417) 836-4147 E-mail: [email protected] Website: https://missouristate.academia.edu/StephenBerkwitz EDUCATION Ph.D. 1999 University of California, Santa Barbara (Religious Studies) Dissertation: “The Ethics of Buddhist History: A Study of the Pāli and Sinhala Thūpavaṃsas.” Advisors: Ninian Smart (Chair), Gerald J. Larson, Barbara Holdrege, and Charles Hallisey M.A. 1994 University of California, Santa Barbara (Religious Studies) Thesis: “Reforming Tradition and Forming Identity in Twentieth-Century Sri Lankan Buddhism.” B.A. 1991 University of Vermont (Religion) EMPLOYMENT AND COURSES TAUGHT Head, Department of Religious Studies, Missouri State University, Fall 2012-present Professor, Department of Religious Studies, Missouri State University, Paths of World Religions, Buddhism, Religions of China and Japan, Yoga and Meditation, Theories of Religion, Sex, Power and Devotion in South Asian Poetry (graduate), Religion, Colonialism, Postcolonialism (graduate), Tantra: Body and Power in South Asia (graduate), Fall 2010-present Associate Professor, Department of Religious Studies. Missouri State University, Paths of World Religions, Buddhism, Religion: Colonialism/Postcolonialism, Theories of Religion, History of Indian Buddhism (graduate), Buddhism in the Modern World. Pali, Sanskrit, Religions of China and Japan, Fall 2004-Spring 2010 Visiting Instructor, Missouri-London Study Abroad Program, International -

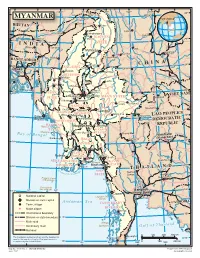

Map of Myanmar

94 96 98 J 100 102 ° ° Indian ° i ° ° 28 n ° Line s Xichang Chinese h a MYANMAR Line J MYANMAR i a n Tinsukia g BHUTAN Putao Lijiang aputra Jorhat Shingbwiyang M hm e ra k Dukou B KACHIN o Guwahati Makaw n 26 26 g ° ° INDIA STATE n Shillong Lumding i w d Dali in Myitkyina h Kunming C Baoshan BANGLADE Imphal Hopin Tengchong SH INA Bhamo C H 24° 24° SAGAING Dhaka Katha Lincang Mawlaik L Namhkam a n DIVISION c Y a uan Gejiu Kalemya n (R Falam g ed I ) Barisal r ( r Lashio M a S e w k a o a Hakha l n Shwebo w d g d e ) Chittagong y e n 22° 22° CHIN Monywa Maymyo Jinghong Sagaing Mandalay VIET NAM STATE SHAN STATE Pongsali Pakokku Myingyan Ta-kaw- Kengtung MANDALAY Muang Xai Chauk Meiktila MAGWAY Taunggyi DIVISION Möng-Pan PEOPLE'S Minbu Magway Houayxay LAO 20° 20° Sittwe (Akyab) Taungdwingyi DEMOCRATIC DIVISION y d EPUBLIC RAKHINE d R Ramree I. a Naypyitaw Loikaw w a KAYAH STATE r r Cheduba I. I Prome (Pye) STATE e Bay Chiang Mai M kong of Bengal Vientiane Sandoway (Viangchan) BAGO Lampang 18 18° ° DIVISION M a e Henzada N Bago a m YANGON P i f n n o aThaton Pathein g DIVISION f b l a u t Pa-an r G a A M Khon Kaen YEYARWARDY YangonBilugyin I. KAYIN ATE 16 16 DIVISION Mawlamyine ST ° ° Pyapon Amherst AND M THAIL o ut dy MON hs o wad Nakhon f the Irra STATE Sawan Nakhon Preparis Island Ratchasima (MYANMAR) Ye Coco Islands 92 (MYANMAR) 94 Bangkok 14° 14° ° ° Dawei (Krung Thep) National capital Launglon Bok Islands Division or state capital Andaman Sea CAMBODIA Town, village TANINTHARYI Major airport DIVISION Mergui International boundary 12° Division or state boundary 12° Main road Mergui n d Secondary road Archipelago G u l f o f T h a i l a Railroad 0 100 200 300 km Chumphon The boundaries and names shown and the designations Kawthuang 10 used on this map do not imply official endorsement or ° acceptance by the United Nations. -

Gender, Lineage, and Localization in Sri Lanka's

GLOBAL NETWORKS, LOCAL ASPIRATIONS: GENDER, LINEAGE, AND LOCALIZATION IN SRI LANKA’S BHIKKHUNĪ ORDINATION DISPUTE by TYLER A. LEHRER B.A., California State University, Sacramento, 2013 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Religious Studies 2016 This thesis entitled: Global Networks, Local Aspirations: Gender, Lineage, and Localization in Sri Lanka’s Bhikkhunī Ordination Dispute written by Tyler A. Lehrer has been approved for the Department of Religious Studies ________________________________________________________ Dr. Holly Gayley, Committee Chair Assistant Professor, Religious Studies ________________________________________________________ Dr. Deborah Whitehead Associate Professor, Religious Studies ________________________________________________________ Dr. Carla Jones Associate Professor, Anthropology Date _____________________ The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in religious studies. IRB protocol #: 15-0563 iii Lehrer, Tyler A. (M.A., Religious Studies) Global Networks, Local Aspirations: Gender, Lineage, and Localization in Sri Lanka’s Bhikkhunī Ordination Dispute Thesis directed by Assistant Professor Dr. Holly Gayley This thesis investigates many of the figures and events that have made full ordinations of Buddhist nuns (bhikkhunīs) both possible and contested -

The Rohingyas of Rakhine State: Social Evolution and History in the Light of Ethnic Nationalism

RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES INSTITUTE OF ORIENTAL STUDIES Eurasian Center for Big History & System Forecasting SOCIAL EVOLUTION Studies in the Evolution & HISTORY of Human Societies Volume 19, Number 2 / September 2020 DOI: 10.30884/seh/2020.02.00 Contents Articles: Policarp Hortolà From Thermodynamics to Biology: A Critical Approach to ‘Intelligent Design’ Hypothesis .............................................................. 3 Leonid Grinin and Anton Grinin Social Evolution as an Integral Part of Universal Evolution ............. 20 Daniel Barreiros and Daniel Ribera Vainfas Cognition, Human Evolution and the Possibilities for an Ethics of Warfare and Peace ........................................................................... 47 Yelena N. Yemelyanova The Nature and Origins of War: The Social Democratic Concept ...... 68 Sylwester Wróbel, Mateusz Wajzer, and Monika Cukier-Syguła Some Remarks on the Genetic Explanations of Political Participation .......................................................................................... 98 Sarwar J. Minar and Abdul Halim The Rohingyas of Rakhine State: Social Evolution and History in the Light of Ethnic Nationalism .......................................................... 115 Uwe Christian Plachetka Vavilov Centers or Vavilov Cultures? Evidence for the Law of Homologous Series in World System Evolution ............................... 145 Reviews and Notes: Henri J. M. Claessen Ancient Ghana Reconsidered .............................................................. 184 Congratulations